ROADSIDE DINING

When I was a child, shortly after the autumn leaves began to fall, Mom would start serving me soup for lunch. The thin tendrils of steam rising up from the bowl were a comforting sight amid the foggy and sometimes frosty Fresno winters. I tolerated the tomato soup and enjoyed the Campbell’s vegetable, but it was the pea soup that really tickled my taste buds. Somewhere along the line, Mom decided to add a dollop of sour cream to the bowl, which made it even yummier. I’m not sure where she got the idea, but every time I have a bowl of pea soup today—with or without ham—I add that spoonful of sour cream to the mix.

Imagine my excitement when I learned that an entire restaurant built around my favorite soup dish not only existed, but was just a few hours up the highway from my home. When I was nine, my parents moved from Fresno to Woodland Hills, at the east end of the San Fernando Valley. Topanga Canyon Boulevard was our gateway to U.S. 101, which could take us east to a game at Dodger Stadium or west toward Ventura and points beyond.

One of those points was a place called Solvang, a town settled largely by Danish immigrants in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Like the Swedish village of Kingsburg along U.S. 99, it had a distinctive Scandinavian flavor, complete with steeply gabled roofs, half-timbered fachwerk facades, and even four windmills. The big attraction for my parents—actually, for my grandmother, who lived with us nearly half of each year—was the selection of shops in the town. Franny (as she liked to be called) loved to shop at the boutiques, gift shops and sweet shops in town.

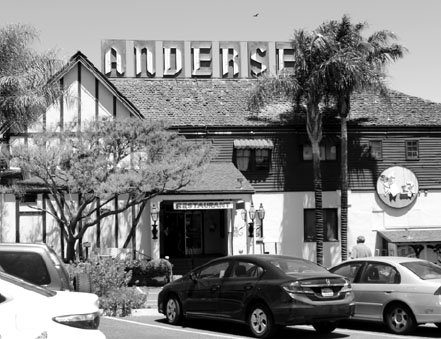

Pea Soup Andersen’s has been a popular roadside stop in Buellton since the 1920s.

Solvang straddles State Route 246, a couple of miles east of Highway 101 and the town of Buellton, which was my favorite stop during the trip. It was there that we’d typically grab lunch at Pea Soup Andersen’s, which featured the same half-timbered style you’d see up the road in Solvang and a windmill of its own. (The name Andersen was a dead giveaway that the Danish settlers had populated the entire Santa Ynez Valley region, not just the town of Solvang.)

It was, and is, impossible to miss the restaurant. Its owners have stationed billboards up and down the highway, from a few yards to hundreds of miles away, each featuring their familiar cartoon mascots, Hap-Pea and Pea-Wee. The rotund, smiling Hap-Pea always appears with a formidable mallet raised over his head as he prepares to bring it down on a chisel-shaped tool held over a pea by his nervous companion, Pea-Wee. A bandage on the side of Pea-Wee’s face implies that Hap-Pea’s aim hasn’t always been true; hence the look of trepidation on the much smaller chef’s face as he eyes the mallet.

The idea came from a comic strip by Charles Forbell that appeared in Judge magazine during the 1930s titled “Little Known Occupations.” One of these showed several craftsmen out in the woods, listening to a bird’s song as they tried to tune their cuckoo clocks. Another depicted a pair of chefs standing at a table, splitting peas one by one as they descended from a chute. It was this second cartoon that caught the eye of Robert Andersen, who received permission to use the characters in his advertising. He hired Disney-trained illustrator Milt Neil to put his distinctive stamp on them, and the result was the iconic pair of mascots that continue to adorn the restaurant’s soup cans, merchandise, and billboards.

The business, however, wasn’t always known primarily for its pea soup. Founded in 1924 by Anton and Juliette Andersen, its biggest selling point was the new electric stove the couple had purchased to cook their meals. The sign outside Andersen’s Electrical Café featured a pair of lightning bolts and advertised sodas, cigars, and candy—nary a word about split pea soup.

Hap-Pea and Pea-Wee, the mascots for Pea Soup Andersen’s, adorn the front of the restaurant on U.S. 101 in Buellton.

It was a modest endeavor at the outset: just three booths and a counter with six stools, but the business grew quickly. Perhaps the biggest advantage it enjoyed was location: Andersen’s Electrical Café opened about the time the coastal highway was diverted through Buellton, and was the first stop along the road after a lengthy stretch of countryside that extends nearly 40 miles heading north from Goleta. By the time travelers heading for Cambria, Monterey, San Luis Obispo, or Salinas made it there in their Model T’s, they were more than ready for a break. Those heading south had to endure a similar distance (more than 30 miles) of rural highway between Santa Maria and Buellton, nearly an hour’s trek in a Model T—if it didn’t break down.

(One destination then, as now, was Hearst Castle in San Simeon. Publishing magnate William Randolph Hearst often withdrew to the retreat he called La Cuesta Encantada—“The Enchanted Hill”—where he would throw lavish parties for movie stars like Charlie Chaplin and Clark Gable, statesmen like FDR and Calvin Coolidge, and American icons including Charles Lindbergh. Journalists who worked for Hearst Newspapers also made the trip—and stopped for sandwich or a bowl of soup at Andersen’s. Among them: O. O. McIntyre and Arthur Brisbane. McIntyre wrote a column titled “New York Day By Day,” and Hearst reportedly paid Brisbane a staggering $260,000 a year for his column “Today,” which at one point boasted 20 million daily readers.)

The Andersens’ restaurant became so popular that a hotel with a full dining room was added in 1928, called “Buelltmore” in a play on the Los Angeles Biltmore, which Anton Andersen had helped open a few years earlier.

Although pea soup wasn’t on the Electrical Café menu at first, Juliette’s family recipe was added three months after it opened; its fame spread rapidly up and down the highway. A mere three years later, the Andersens found they had to order, literally, a ton of peas to keep up with the demands. They stacked them up in the window of the café, which they declared to be “The Home of Split Pea Soup.”

By the 1980s, the restaurant was trucking in 55 tons of peas a year in 100-pound sacks from Moscow, Idaho, and attracting celebrities such as John Travolta and comedian Flip Wilson. Its evolution from Electrical Café to pea soup mecca, however, didn’t happen all at once. The definitive step in that transformation took place courtesy of the founders’ son, Robert Andersen, after World War II. The restaurant had closed during the war, when the hotel was used to house service members stationed locally, but it reopened after the Axis forces surrendered and, in 1947, changed its name to Pea Soup Andersen’s.

In that same year, the postwar construction boom brought significant change to Buellton in the form of a new highway alignment through the center of town. The expressway was completed two years later, and Robert Andersen was so enthusiastic he wrote a letter to the state Division of Highways commending it for the changes.

Before the new expressway, it had been, in the words of one merchant, “a small crossroads, strip developed, traffic-bottlenecking village.”

But now, all that had changed.

In his August 1949 letter to the state highways agency, Andersen wrote: “We believe that, due to the new outer highway arrangement, the future highway business life of Buellton as a service town, and Andersen’s as a roadside restaurant and hotel, is well assured.”

The use of the term “service town” in Andersen’s letter proved to be prescient. The next month, California Highways and Public Works magazine writer J. F. Powell bestowed upon Buellton the title of Service Town, U.S.A. Its location at the intersection of U.S. 101 and State Route 150, roughly halfway between Santa Barbara and Santa Maria, made it “a logical stopping point,” Powell wrote. Now, it had a road built to accommodate the traffic: According to Andersen’s letter, more than 250,000 motorists a year stopped to eat at Andersen’s.

So many people used the road, in fact, that Buellton became not just a service town, but a service station town.

Powell wrote in 1949 that “Buellton, despite a population of only 250, today boasts on its outer highways alone no less than eight service stations.” And old postcards show Chevron, Shell, Seaside, and Associated gas stops, among others, along the short segment of gently curving highway.

The expressway was itself bypassed by the new freeway alignment in 1965—the same year Robert Andersen sold the restaurant to Vince Evans—but the road remained a community focal point as the Avenue of Flags, a milelong section featuring eight large American flags atop flagpoles forged by a local blacksmith. These were dedicated by then-Governor Ronald Reagan in September 1968.

As for Andersen’s, Evans expanded the business with a second location in Santa Nella, on Interstate 5 not far from Los Banos. Other restaurants opened during the 1980s in Mammoth Lakes, Carlsbad, and along Highway 99 in Selma. None of them lasted, although the Selma location—complete with a windmill—survived as the Spike N Rail Steakhouse, still serving pea soup and still located on a street called Pea Soup Andersen Boulevard.

Avenue of the Flags, old U.S. 101, entering Buellton from the north.

The Andersens’ restaurants in Buellton and Santa Nella, together with their roadside hotels and gift shops, remain open as well. In 2012, they reported serving 500 to 600 gallons of their specialty a day, much of it through orders of their all-you-can-eat pea soup Traveller’s Special. You can add bacon bits, chives, cheese, or croutons to your order.

And, of course, sour cream.

HISTORY ON A CLAMSHELL

If Andersen’s is a couple of years older than the highway’s formal designation as U.S. 101, there’s another eatery that dates back more than half a century earlier: the Old Clam House in San Francisco.

Of course, it wasn’t called “old” at the beginning. Its original name was the Oakdale Bar & Clam House.

It sits in an industrial district on Bayshore Boulevard—an old alignment of 101—and was there when the “boulevard”—or its predecessor—was a wood-plank road and the name “bayshore” could have been taken literally. Back when the restaurant opened in 1861 (yes, that’s 18, not 19), the planks were necessary to carry horses and buggies across the marshy swampland that bled out into the ocean. The restaurant itself sat on Islais Creek, a freshwater stream that emptied into San Francisco Bay.

Nowadays, the road is about a mile from the actual shoreline. Over the years, enterprising businessmen used earth and debris to create an ever-growing gap between the highway and the eatery. Ten years after the marsh was filled, 100 buildings had gone up there, many of them belonging to butchers who established their own district in what had once been an area dedicated to the fishing trade.

Debris from the catastrophic 1906 earthquake was later added to the growing landfill, removing the restaurant and its clams even farther from shore.

A trolley crosses a freeway overpass near the Los Angeles Civic Center in 1954. © California Department of Transportation,

all rights reserved. Used with permission.

But the eatery itself remained, even as a McDonald’s went in around the corner.

Today, the city’s oldest restaurant to operate continuously in the same location still serves up mussels, shrimp, roast Dungeness crab “in our secret garlic butter sauce,” and, of course, clam chowder (in a bread bowl or a cup, if you prefer).

RIDING THE RAILS

Small as Buellton was, Andersen’s wasn’t the only game in town when it came to roadside dining. Ed Mullen had a place—and a gimmick—of his own, in the form of two old streetcars, which he converted into stationary dining cars.

Mullen opened the café a mile and a half north of town just after World War II, in 1946. According to one account, he had worked as a steward on actual dining cars and managed to get his hands on a pair of Type-B Huntington standard models, built in St. Louis in 1911 and used on the Los Angeles Railway’s Yellow Line.

The line had been developed by Henry Huntington, for whom the Huntington Library near Pasadena is named (before it became a library and an art museum, it was his residence). In 1898, Huntington had purchased the Los Angeles Railway lines, three years before he formed the larger Pacific Electric Railway system in the area. The former was known as the “Yellow Car” line, while the latter was known as the “Red Car” system.

Huntington died in 1927, and his estate continued to operate the rail lines until they were sold in 1944. With the end of the war, ridership began to decline as a new era of automotive travel got underway. Once hostilities ceased, Americans quickly turned their attention from rationing rubber and gasoline for the war effort, taking to the highways in record numbers. It was here that Mullen saw an opportunity: More motorists than ever would be whizzing up and down U.S. 101 between Los Angeles and San Francisco, and the dining cars would be an eye-catching way to lure them in for a midday meal.

The two railcars he would use for his diner were decommissioned in 1944, and Mullen trucked them up the road from Los Angeles. Customers entered the establishment through the main building in the center, and they could enjoy a meal in one of the dining cars, which were situated on either side. Mullen attired his waitstaff in special uniforms that featured conductors’ caps, and left in place the old streetcar signs that declared, “Passengers will have fares ready.” At some point, he even installed gas pumps to boost business.

Unfortunately, the same renewed fervor for automotive travel that made the café seem like a good idea proved to be its undoing. Shortly after the business opened, the Department of Highways announced its plan to bypass the section of road where the business had opened in favor of a sleek, new section of highway. The old highway became a mere frontage road called Jonata Park Road.

As business began to decline, Mullen sought to draw customers with a different sort of attraction. When members of the Lompoc Model T Club approached him with an offer to lease his land for use as an oval racetrack, he took them up on the idea. The “T” Club Speedway, as it was called, offered fans admission to the races for a dime in the summer of 1950, and they could watch the action from a grandstand built on a hillside behind the track.

The new attraction, however, failed to stem the loss of business as cars continued to roar past the diner on the new highway. In 1955, a new owner named Jack Chester took over the business and added a Seaside Service Station, but more plans for expansion of U.S. 101 led the Department of Highways to erect a barrier across the roadway, blocking access to the restaurant and effectively putting it out of business.

It closed for good in 1958 and remained vacant for many years until the early 2000s, when the land was rezoned for residential use even as the then-owners worked to restore and reopen the diner. With those efforts stymied, they tried to sell the streetcars or even donate them to the city of Buellton … which expressed no interest in assuming ownership. A retired contractor from Cayucos finally came along in 2012 with plans to move them onto a vacant lot he owned at Highway 41 and Main Street in Morro Bay—a feat he managed, only to run into permitting problems with the city of Morro Bay.

The following year, they were moved again: this time up the coast to Arroyo Grande, where they became part of a display at the site of the Bitter Creek Western Railroad. The site, operated by Karl Hovanitz “for the benefit of all his friends who like to play with trains,” includes a 7.5-inch gauge railroad with more than a mile of mainline track, a number of sidings, and two rail yards.

Carney’s features railcar dining along Ventura Boulevard in Studio City.

After all those years, the dining cars were right back where they started: on the rails.

(For those who still want a railcar dining experience on the Old 101, you can grab a bite at Carney’s Restaurant on Ventura Boulevard in Studio City. The restaurant, which brags that it serves “probably the best hamburgers and hot dogs … in the world,” consists of a kitchen car built in 1938 and a dining room car from four years later, both once used by the Southern Pacific.)

FJORD’S

Another distinctive shape in highway dining was Fjord’s, a chain of budget buffet restaurants with a slanted, peaked-roof design that made each one look like the bow of some angular land-bound ship rising out of the waves.

The building was hard to miss on State Street, the former 101 alignment, at the northern end of Ukiah, and its billboard-type sign was sure to attract travelers who stopped there for the nearly quarter century it was in business. Featuring a menu of cold salads, chicken, cheeses, and other standard buffet fare, it attracted travelers, athletic teams, and a host of others during its heyday. According to one newspaper account, it wasn’t unusual for teams from Humboldt State, Chico State, and other colleges or high schools in the region to stop in after games for a visit to the buffet.

Founded by owner of a Sno-White Drive-In franchise, the Ukiah Fjord’s was part of a chain of “Smorg-ettes,” buffet restaurants that operated for a couple of decades starting in the mid-1960s. You could find them in places like Chico, Bakersfield, Fresno, and a couple of blocks off the Cabrillo Highway south of Santa Cruz—where the building was later converted into an IHOP. There were even locations in Portland, Oregon, and Guam (yes, Guam).

(As a Fresno native, I looked up the location there and found it at the northwest corner of Blackstone and Dakota, where it opened its doors in 1967 but was out of business by 1972, having been replaced by Sun Stereo. The building, which is still there today, was built in 1962—predating Fjord’s—so it doesn’t have the distinctive slanted/peaked roof.)

Fjord’s in Ukiah has gone by the wayside since this photo was taken in 2016; an In-N-Out Burger took its place.

Fjord’s offered both a smorgasbord and a full menu. All-you-can-eat lunches were $1 there when it opened, with dinners and Sunday meals that cost a little more, and discounted prices for children. Desserts were extra.

The owners in Ukiah, Lyle and Zera Hobby, were avid bowlers who sponsored two teams at Yokayo Bowl—which, conveniently, was right next to the restaurant. Their son Ted later took over as manager, but he died at the age of 42 in 1973. New owners took over the next year.

The Ukiah restaurant, which also featured a gift shop, stayed in business until 1988, housing a bagel house briefly after that but then remaining vacant for the next couple of decades. By mid-2016, it had been purchased by the Southern California-based In-N-Out Burger chain. The building was torn down in August of that year.