THE CABRILLO HIGHWAY

A section of Highway 1 facing north as it passes through Pismo Beach, just before rejoining U.S. 101.

The Cabrillo Highway is U.S. 101. Sometimes. And in some places. It’s also State Route 1—even though that scenic highway is better known as the Pacific Coast Highway for much of its length.

Confused yet?

It’s easy to lose your bearings when one road is sometimes two and, at various times in our state’s still-young history, has been called by different names.

Until 1964, the segment of road that ran along the coast in the Los Angeles area was called U.S. 101-A. The “A” identified it as an alternate to the main alignment of U.S. 101, which was later converted into Interstate 5 south of the Hollywood Freeway. The “alternate” coast route in that area became State Route 1 when the federal government turned over responsibility for its maintenance to California.

Along some segments along the Central Coast, however, the state and federal highways share the same strip of asphalt.

They have to.

Pavement from an old alignment of the U.S. 101 Alternate goes nowhere, stopping where the ocean has eroded the coastline at Point Mugu.

In areas where the coastal mountains hug the seashore, there’s simply no room for two roads, and the Cabrillo Highway takes on a split personality as both 1 and 101. If you drive up the coast between Ventura and Santa Barbara, you’ll see what I mean. Before the construction of the coast highway, the only viable north-south route here was inland, along the Casitas Pass Road (now State Route 150), still the only alternative for travelers along this stretch of coastline.

My wife and I discovered that firsthand in December 2015, when a fire closed the coast highway for several hours as we were heading south for a holiday meal with her family. With all traffic diverted onto the mountain road that wound around the backside of Lake Casitas, we spent more than two hours covering a distance we would have traversed in one quarter that time had the coast highway been open.

This scenic back route, which had been used for stagecoach travel since 1878 and opened to automobiles in 1897, was once as deadly as it was picturesque for travelers heading north from Los Angeles through the foothills to Santa Barbara. In the late summer of 1911, for instance, a particularly jarring tragedy claimed the lives of a physician and his wife, Arthur and Grace Pillsbury.

The Pillsburys and their three children had set out from their home in Hollywood at 8:30 on a Sunday morning on a trip to Stanley Park, a popular mountain resort on Rincon Creek in the Santa Ynez Forest.

Just a mile away from their destination was Shepherd’s Inn on the Ventura-Santa Barbara County line, a rustic way station popular with travelers up and down the coast.

The Pillsburys never got that far.

Instead, as their six-cylinder Auburn 30 traversed the Wadleigh grade 10 miles from Ventura, they came upon a slide that cut into the roadway so severely that it barely left room for a single car to pass. Undaunted, Dr. Pillsbury steered as close to the embankment as he dared—too close, as it turned out. His inside fender plowed into the earth and, in attempting to correct his course, the good doctor failed to negotiate a sharp turn. Instead, his car went plunging over the edge, rolling repeatedly as it fell almost 50 feet to the bottom of the canyon beside the road.

The children (a girl and two boys, ages 13 and 6) screamed as they were thrown from the back seat of the car as it hurtled down the incline. Landing in the brush, they suffered bruises and, in the case of the 13-yearold, a badly sprained left ankle. They were, sadly, left as orphans. Rescuers discovered Dr. Pillsbury’s body 15 feet from the Auburn, which finally came to rest after striking a tree. They found his spouse, also lifeless, a short distance away.

Friends attributed the accident in part to the physician’s “mania for speed.” He had informed his wife a few months earlier that he was “going in for racing as a pastime,” a development that had worried her to such an extent that she told neighbors of a premonition before they departed that she might not return alive.

Motor Age magazine’s Paul Gyllstrom wrote that the pass had, indeed, taken its toll in human lives, “but chiefly among the careless,” and described it as one of the scenic wonders of the West.

“Motorists who visit southern California and fail to go through it at the proper time of year will have missed one of the sights,” he said. “One might just as well go to Seattle without seeing Mount Rainier, or Tacoma without seeing Mount Tacoma, and the Yosemite (Valley) without gazing on Half Dome, as come to this part of the country without traversing the Casitas.”

Despite this, the Oxnard Courier, in reporting the tragedy that claimed the lives of Mr. and Mrs. Pillsbury, noted that the condition of the road was at least partly to blame. In an editorial comment embedded in the news report, the Courier remarked that “the grades and curves on the Casitas are extremely dangerous, especially so to drivers whether or not they are experienced when they do not know the roads and all the ins and outs.” The accident, the newspaper declared, “brings forcibly to mind the urgent necessity of the immediate construction of the Rincon sea-level road between Ventura and Santa Barbara, thus doing away with the travel over the dangerous Casitas Pass.”

CAUSEWAY AND EFFECT

The Rincon Road was meant to provide a more direct (9 miles shorter) alternative to the winding mountain pathway, running directly along the coast from Ventura to Santa Barbara. The challenge was carving out a path for the roadway between the sheer mountains and the surf that slammed into their base at high tide.

The solution? A series of three wooden causeways—20 feet wide and 2,000, 400, and 4,000 feet in length, respectively—to raise the road above the pounding surf.

“The method of construction is simple,” Paul Gyllstrom wrote in the October 17, 1912, issue of Motor Age. “Eucalyptus piles are driven, cross beams are laid, then the floor of the causeway and the wooden railings on each side.”

The causeways, like piers running parallel to the coastline, gave the waves somewhere to go without inundating the road that now ran over the top of them. Passengers could peer out the window and stare down through the spaces between the planks, where they could see the white foam crashing up against the shoreline beneath them.

The causeways—built at a cost of $47,000—opened in November 1912 to great pomp and celebration, with a crowd estimated at 20,000 to 30,000 in attendance.

But the new road wasn’t perfect. The steep hills beside the road were prone to mudslides, such as one in 1922 that buried a couple of cars to the tops of their doors between two of the causeways and deposited boulders on the highway. From the other side, the pounding surf took its toll on the causeway pilings, which required extensive maintenance, and nails sticking up through the wood punctured their fair share of tires.

Despite the hazards and a large number of accidents reported on the sea road, motorists hummed along at a speedy clip that came to be known as the “Rincon gait.” Was the new route really safer than the Casitas Pass? That was open to question.

Regardless, it wasn’t long before the highway builders found a better way to navigate the coastline than a rickety wooden road: The causeways were in use for just slightly more than a decade, replaced in 1924 with a paved road set down on earth fill.

The Rincon Sea-Level Road, a wooden plank causeway, was an early attempt to create a coastal highway in Ventura County. © California Department of Transportation, all rights reserved. Used with permission.

U.S. 101 at Olive Mill Road in Montecito, 1938. © California Department of Transportation, all rights reserved. Used with permission.

THE (LEGAL) BATTLE OF GOLETA

As the Cabrillo Highway enters Santa Barbara, it remains both 1 and 101, and it’s common to encounter slower traffic along the highway through town.

It was once even slower than it is today, with the town being the site of the only traffic lights on 101 between L.A. and San Francisco. Beginning in 1948, four stoplights signaled motorists to stop and spend a little time in Santa Barbara—even if they didn’t feel like it. The last of the four, at Anacapa Street, winked off for the last time at midmorning on Wednesday, November 20, 1991.

“These lights are almost an anachronism of the ’40s and ’50s,” Caltrans engineer Mike Mortensen told the Los Angeles Times on the eve of the light’s demise. “They kind of remind me of Route 66, with the motels shaped like wigwams—part of a more simple life.”

“I think of it like the Golden Spike,” that linked east and west via the transcontinental railroad, he added. “In a way, it’s a closing of the frontier.”

The Cabrillo continues as an east-west highway along the coast for more than 30 miles from Santa Barbara through Goleta and past El Capitan State Beach to Gaviota. An earlier alignment, west of the modern freeway, is a wide boulevard known as Hollister Avenue that runs about 14 miles on either side of Goleta. That’s where you’ll find the historic Barnsdall-Rio Grande service station that dates from 1929.

If “Hollister” sounds familiar as the name of a city to the north—in San Benito County, a couple of miles east of U.S. 101—there’s a reason for that. Both that town and the street are named for the same man: William Welles Hollister, who founded a sheep ranch near the present site of Hollister (the town) and made a fortune by selling wool during the Civil War. After the war ended, he traveled south and began buying large tracts of land in the Santa Barbara area.

One of those tracts was Tecolotito Canyon, which belonged to Nicholas Den, whose daughter, Katherine Den Bell, would famously predict the Ellwood oil strike several decades later. Den, who died in 1863, had decreed in his will that his land could not be sold until his youngest child—then just one year old—reached adulthood. But Hollister had two important assets: money and determination. He offered the Den heirs between seven and a hundred times what the land was worth, and the family, hit hard financially by a devastating drought, accepted.

If you exit at Mariposa Reyna in Gaviota and drive a short way inland, you’ll be treated to this view of old concrete on the west side of the road.

Hollister built a lavish estate at the end of a private road through the canyon, which extended from the county road that would later be named Hollister Avenue (old U.S. 101). He widened the county road to 100 feet, lined the entrance to the estate with palm trees, and renamed the canyon Glen Annie, in honor of his wife, Annie James Hollister. Unfortunately, Hollister’s wife and sister didn’t get along, and even though they shared an expansive mansion, Annie insisted that her husband choose between her and his sister.

He refused, instead building an entirely separate, second mansion for his wife. The mansions and their gardens—planted with flora that ranged from olive trees and grapevines to banana trees and lilies—became a showplace, and everyone was happy.

Except for Katherine Den Bell.

Nicholas Den’s eldest daughter didn’t like the way the family lawyer had handled her father’s will, so she hired another attorney—a man from San Francisco named Thomas Bishop—to investigate the matter. As it turned out, Hollister had bought the land from the estate without bothering to seek the probate court’s approval. It was just the sort of loophole Bishop needed. He agreed to take the case on the promise that he would receive half of the disputed land if he won, and nothing if he lost. To Bell’s way of thinking, 50 percent of a possibility was better than 100 percent of nothing, so she accepted. Thus began an epic courtroom battle that one historian dubbed the “legal drama of the nineteenth century” and dragged on for fourteen years.

Hollister won the first round, but lost on appeal, and his own appeal was ultimately rejected. By the time the California Supreme Court had decided the case, Hollister had been dead for four years, and his widow was left to retrieve her belongings from the home that was no longer hers. Just 15 minutes after she departed, the mansion went up in flames, but though suspicion immediately fell on her, no one could ever prove that Annie Hollister was guilty of arson. She died in 1909, steadfastly claiming that she had no idea what caused the fire.

Bishop, as promised, received half the land in payment for winning the case. That land—a parcel bordered by U.S. 101, Glen Annie Road, Cathedral Oaks Road, and Patterson Avenue—remained in his family until 1959 and is still known as Bishop Ranch.

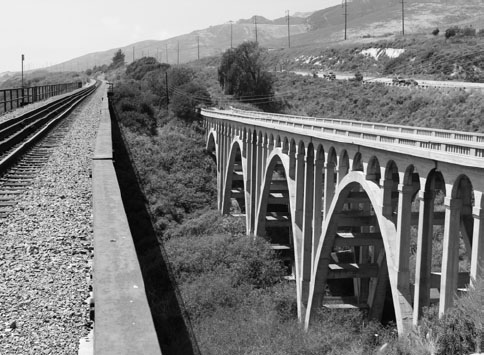

A bridge from an old alignment of U.S. 101 crosses Arroyo Hondo along the Santa Barbara County coastline near Gaviota. The current alignment can be seen in the background.

West of the ranch, El Camino Real continues a more-or-less direct path toward Gaviota, but it wasn’t always that way. A 1903 map shows Hollister Avenue (which would become the first alignment of 101) veering abruptly inland at a 45-degree angle on what is now Las Armas Road—a short stretch of pavement that’s cut off by the modern 101. On the other side of the highway, the old road starts up again as Winchester Canyon Road, then veers westward onto private land and undergoes another name change, to Armas Canyon Road.

The reason for the directional change was a steep hill that stood directly in early travelers’ path.

In 1912, Santa Barbara County got so fed up with the detour that it commissioned road builders to smooth the way westward by leveling the hill. Even so, El Camino Real’s route then still wasn’t as straight as the modern freeway’s. It meandered a bit here and there to the north of the modern alignment, becoming quite curvaceous indeed as it approached Gaviota. If you exit the freeway at Mariposa Reina and drive up the hill northward a short way, you’ll be able to see a well-preserved segment of the original concrete curving down over a gently sloping hillside west of the road. (Another, much less well-defined segment of the old highway is visible on the east side of the road).

A much newer segment of the road on the other side of the current highway is also visible in the same general area. It’s the old Arroyo Hondo Bridge, built in 1918 and now accessible via a lookout point if you’re traveling east on 101. Its concrete arches retain both their beauty and their functionality, but they’re no longer open to vehicle traffic, having been closed in the mid-1980s. You can still walk the length of the bridge and see its pavement disappear at the west end in a mosaic of cracked asphalt, weeds, and wildflowers. To the south, the last thing you see before the Pacific Ocean is a steel railroad trestle bridge that runs parallel to the concrete arches and makes the scene even more impressive.

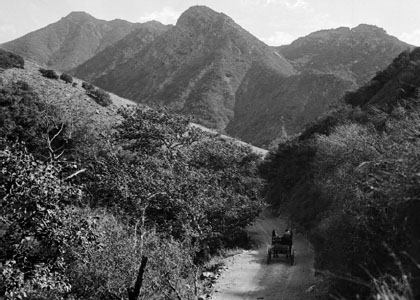

Gaviota Pass, early 20th century. California Historical Society, public domain.

The modern freeway doesn’t travel over a bridge at all, its foundation having been laid on solid ground. It’s a bit east of Gaviota on the modern freeway.

Speaking of Gaviota, its population is listed as less than 100 people, but you’ll be hard pressed to see any sign of a community from the highway. The Hollister Estate Company built a general store there in 1915, and it was so far away from anything else in either direction that it quickly became a hub of activity. It featured a service station—at one time selling Chevron gasoline—an auto court, a dance hall, and post office while offering telephone access along with groceries and clothing for sale.

Free-spirited surfers drawn to the waves and truckers lured by the prospect of some hot coffee wandered in and out of the café until it was sold in the late 1960s and demolished in 1970 by a big-city concern that wanted to develop 17 miles of coastline into a residential and recreational community. Among the planned attractions: a clear plastic tunnel through which people could walk down to the beach, and a lighthouse.

The developer started by reinventing the wheel—or in this case, the rest stop—by building a Cape Cod-style restaurant and service station. Further plans called for a “Drake Point Park” with shops, a coin-op laundry, a teen center, swimming pools and courts for shuffleboard, badminton, tennis, and paddle tennis.

None of it ever happened.

The company went bankrupt, and the restaurant went through a series of owners, among them a commune that specialized in organic farming. One of the few events considered newsworthy by the press was the Gaviota Village Bicentennial Backgammon Tournament, in which Diane Stephens defeated Andy Smith for the championship. The restaurant eventually closed after someone stunk up the place by stuffing sea snails into the ventilation. The abandoned building burned to the ground in 2002, and six years later, the land once destined to be a grand development became, instead, Gaviota State Park.

THE GAVIOTA TUNNEL

Gaviota, where it veers abruptly northward and through the Gaviota Tunnel, was carved out in 1953 for the highway’s northbound lanes. (There’s no tunnel for the southbound lanes, to the west, which use the narrow Gaviota Pass—a key site in the Mexican-American War of 1846. Mexican forces waited in ambush here for John C. Frémont’s troops, but the U.S. forces never came. Learning of the ambush, they traveled southward by the San Marcos Pass instead and captured Santa Barbara.)

The pass was a challenging obstacle for early travelers, who had to find a way across Gaviota Creek, which had carved out the narrow canyon that linked the coastal plain with the Santa Ynez Valley to the north. The canyon was so narrow in the mid-19th century that workers had to chisel away the rock to create an opening large enough for stagecoaches to pass through. William Brewer, who worked on the first geological survey of California in 1861, remarked that the Gaviota Pass was the only break in the sandstone of the Santa Ynez Mountains for “a hundred miles or more.”

“At the Gaviota,” he wrote, “a fissure divides the ridge, but a few feet wide at the narrowest part and several hundred feet high.”

Just two years before Brewer worked on that survey, workers used dynamite to carve out the first county road at a cost of $32,000 and built a wooden bridge over the creek. Standing guard over that bridge was—and still is—a rock overhang that early visitors to the place imagined looked like an “Indian head.” The name stuck, and the rock became such a familiar sight that plans for its removal for safety reasons were scrapped in response to a protest, and other adjustments were made to ensure travelers safe passage.

Over the years, more improvements to the road were made, as well. In 1915, workers replaced the wooden bridge with a steel suspension bridge that served to guide motorists across the creek for the next 16 years. After that, highway workers installed a narrow concrete bridge that preserved the zigzag course over the canyon and forced any driver crossing to stay alert and maintain a safe (read “slow”) speed.

Still, it was an improvement over its predecessor. Workers actually realigned the creek itself to create a more direct pathway. Three years later, in 1934, they straightened the road on the ocean plain, reducing the number of curves there from 41 to just 10.

Gaviota Pass in 1935, before the modern tunnel widened the highway to four lanes through the close quarters between the mountains. © California Department of Transportation, all rights reserved. Used with permission.

The Gaviota Tunnel, which opened in the 1950s, as seen today.

It wasn’t until 1952 that the Department of Highways set about widening the road through the pass by carving out a tunnel from the rock on the eastern side of the canyon. Workers had to do all their digging from the south end of the mountain because blind curves on the north side made it impossible for earthmovers to cross the existing highway safely. When they completed their work in May 1953, they had carved out a passage that measured 435 feet long, 35 feet wide, and 18 feet high, encased in 18-inch-thick concrete. The lights inside operated on the first power lines to be installed in Gaviota Valley.

The tunnel’s been featured in everything from Dustin Hoffman’s breakthrough film, The Graduate, to the Saturday Night Live spinoff comedy Wayne’s World 2—which both featured actors driving the wrong way in the northbound tunnel, heading south. The landmark also makes appearances in the film Sideways and the videogame Grand Theft Auto V (where it’s called Braddock Tunnel).

The 11-mile stretch of road north of the Gaviota Pass to Buellton was among the last paved sections. Opened to traffic in 1922, it eliminated a detour via Solvang that one report described as “very provoking indeed to the motorist who was used to paved highway, and quite a shock to his car.”

GHOST TOWN

Shortly after you leave the Gaviota Tunnel heading north, U.S. 101 and State Route 1 diverge again at a crossroads known as Las Cruces, which evolved over time from a Spanish rancho into a stagecoach stop, then a highway crossroads.

There’s not much there now, and if you blink, you’ll pass by without seeing it. Even if you get out of the car and stare, you’re liable to miss it. There’s very little left except for a single building and an old truss bridge just to the west of 101 south of its junction with Highway 1. The Park Road Bridge, as it’s called, was originally made of wood and dates back to 1909.

Las Cruces dates from an 18th-century graveyard in the area, where the Chumash buried more than 100 of their dead. Franciscan friars later replaced the tribal grave markers with crosses: hence the name Las Cruces. Miguel Cordero, a career soldier, built an adobe home there in 1833 and received a land grant of more than 8,000 acres four years later. On his death in 1851, the land passed to his children, who built six more adobe structures—including the one now referred to as the Las Cruces Adobe.

In the early 1860s, a grasshopper infestation and two years of drought all but wiped out many ranchers in the area. During this time, the Corderos sold a number of undivided interests in the rancho to keep their heads above water. Such sales gave each buyer a common—but not exclusive—claim to all the rancho’s assets.

Among those buyers was a sheepherder named Wilson Corliss, who saw an opportunity to boost his profits when he heard about a plan to reroute the stage line closer to Las Cruces. The new route was approved, and Corliss lost no time in building a new house not far from the crossroads that would double as a way station.

Las Cruces, north of Gaviota, was a highway stop with services and food available in the 1930s. Now, it’s largely deserted, and the businesses that once thrived there are long gone. Curt Cragg and the Buellton Historical Society.

But what looked like a shrewd business move turned out to be a fatal mistake.

A few days after Corliss and his wife moved into their new house, they were beaten and locked inside—and the place was torched. The body of a shepherd who lived with them was found a couple of weeks later, wedged between some rocks.

Suspicion eventually fell on Bill, Elize, and Steve Williams, three brothers who lived in the building now known as the Las Cruces Adobe and had been competing with the Corlisses to set up a stagecoach stop. They’d even gone so far as to remodel the adobe’s interior so it could serve as a hotel, as well as building a barn and corral for stage horses. They certainly had a strong motive for murder, but what was the evidence?

One woman testified that the Williams brothers had offered her money to lace the Corlisses’ milk with strychnine, but without any corroboration, the case was deemed too weak to secure a conviction. Some suggested that the brothers be sent to the gallows to elicit a confession, but their accusers decided that would be going too far and, seeing no other alternative, released them.

If you believe in karma, what happened next would surely qualify: Shortly after their acquittal, two of the three brothers were murdered in an apparent robbery while they were camping in San Luis Obispo. Authorities later arrested a man wearing one of their gold watches and hanged him for their murders.

The adobe, meanwhile, and some of the ranchland eventually fell into the hands of William Welles Hollister—the same man who built the palatial Glen Annie estate in Goleta—and two local landowners named Thomas and Albert Diblee. They had built a wharf in Gaviota to facilitate shipping exports overseas, and acquiring a stage stop up the road made perfect sense. The Williams brothers might have failed to develop the adobe as a stage stop, but the Corliss murders and the destruction of their home left it as the most suitable location.

Hollister built a new barn to replace the one the Williams brothers had constructed there, and the stage road passed between it and the adobe—which was serving as a hotel, general store, and post office under the management of R. J. Broughton by 1877. It also, at various times, housed a saloon, a gambling hall, and even a brothel … an interesting combination considering that Broughton became sheriff of Santa Barbara County in 1882, a position he held for 13 years until his death. After that, the adobe no longer housed a hotel, but confined its business operations to a café and bar.

When the railroad and highway replaced the stage line, it became a highway stop during the 1920s and ’30s. Service stops like Las Cruces sprang up along major highways during this era between major towns like Santa Barbara and Santa Maria. There wasn’t much in either direction, and at a time when cars moved more slowly and frequently broke down, Las Cruces was well situated for travelers who needed to stretch their legs, refill their gas tanks, or grab a bite to eat.

Such highway stops still exist today on roads such as Interstate 5, which rambles across mile upon mile of empty land on the west side of the San Joaquin Valley. Clusters of gas stations, diners, and convenience stores huddle around the highway at exits for Patterson, Los Hills, and Kettleman City, beckoning travelers with soaring lighted signs visible from miles away on a clear summer night.

This trestle bridge, visible from U.S. 101, is one of the few indications that a town once existed at Las Cruces.

Things were simpler in the heyday of Las Cruces. A Model T might rumble across the Park Road Bridge and into town at 15 or 20 mph and pull up to get some Chevron gasoline at the El Camino Garage, the first stop on the short strip of roadside buildings. Eugene and Marguerita Tico Hess ran the Hess Garage, offering “general repairs” and “accessories for all cars” until about 1938, when they packed up and left the area. Farther on were the Las Cruces Store and Las Cruces Station, which dispensed Shell brand gasoline.

In the meantime, cattle drives continued through Gaviota Pass on until the end of World War II, with highway patrol officers warning motorists of oncoming bovine traffic.

The town withered after a new highway alignment passed it by, and newer, more dependable cars that could go farther on a tank of gas rendered it an unnecessary detour on a trip up the coast. If you could make it to Buellton on 101—or Lompoc on the Pacific Coast route—why bother to stop at Las Cruces?

Fewer and fewer people did, and eventually, the businesses all closed. All that’s left there now is one old, falling-down structure, and you can’t even get to the town from U.S. 101 today. There’s a locked gate between the highway and the Park Road Bridge, and you have to go up Highway 1 toward Lompoc and double back on San Julian Road if you want to see the place up close.

Legend has it that the ghosts of three prostitutes from the old stagecoach-era brothel still haunt what’s left of the rickety old building, one having committed suicide and the other two having been strangled by a crazed customer. The spirit of a man wearing a long black coat and a wide-brimmed hat also supposedly haunts the place, the veteran of a long-ago gunfight in which he came out on the losing end.

SPLIT ROAD

North of Buellton, at Los Alamos, the highway splits again, and for a short distance, there are three north-south alternatives for heading up the coast.

The original route for U.S. 101 between Los Alamos and Santa Maria ran between the Cabrillo/Pacific Coast Highway and the current 101 Alignment until 1933, following the route now occupied by State Route 135. This Old 101 Alignment merges again briefly with Highway 1 south of Orcutt, then enters Santa Maria as Broadway, the main north-south thoroughfare through town. Despite an abundance of modern development, this section of road retains much of its historic character. Old motels and a few vintage neon signs are visible along the length of the old highway through Santa Maria, and a short section of the original, narrow concrete is visible at its north end, where the road veers back to rejoin the modern 101 Alignment. (Just look for the white picket fence on the left near Priesker Lane as you head north).

In years past, at the south end of town, travelers were greeted by a brightly lit tower in the shape of a tall, slim oil derrick, one of about 30 such towers lining the highways in California, Oregon, and Washington. Twenty of those were in California, with the majority along U.S. Highway 99 but about one third of them at various points on U.S. 101.

The 125-foot towers, with Richfield spelled out vertically on one of its three steel-beamed sides, were built in the late 1920s and placed strategically along the highway to signal motorists that it was time to stop and fill ’er up. They were also designed to act as points of light to guide aviators along what became known as the “Great White Way.” On 101, you could find them just north of the Mexican border at Palm City, as well as in Capistrano Beach, Santa Maria, Paso Robles, Chualar, and Santa Rosa. There was also a beacon—but no station—in Santa Barbara, and the toll gate to the San Francisco Bay Bridge bore two 135-foot towers with the Richfield name, although no towers were placed there.

The era of the Richfield Beacons was fleeting. The company ran into financial problems with the onset of the Great Depression, and within a few years, aviators no longer needed the beacons to serve as their guides. In the span of a decade, the lights went out on most of them, and several were torn down. These days, all the 101 towers are long gone, although a couple of examples remain along Highway 99 in northern California, at Willows and Mount Shasta. (See my book Highway 99 for photos and a detailed look at the Beacon stations).

Old gas pumps in Los Alamos.

Peeking inside the old Richfield Beacon station through a circular window.

The beacon tower three miles south of Paso Robles remained in place until it was finally removed in 1995, but the long-closed gas station is still there on Theatre Drive, a segment of the old alignment bypassed by the current freeway. The locked Spanish Mission-style building now serves as a bus stop in front of a modern big-box shopping center that’s home to such retailers as Target, Bev Mo, and Orchard Supply Hardware.

The Santa Maria tower lasted a while, too, flickering on for the first time during a rainy opening-day celebration on April 18, 1929 and making its curtain call in 1971. Both the gas stations were built a bit south of town, because the intent was to catch travelers before they reached the city limits—and other service stations, of which there were plenty in Santa Maria at the time. By one count, a two-mile stretch of Broadway was packed with some two dozen businesses that sold gas, even though Santa Maria’s population at the time was just 7,000.

Plus, the beacon stations were designed to be outside the city limits because Richfield had big plans for them: They weren’t supposed to be just service stations, but hubs for small communities that the company envisioned growing up around them. Richfield itself planned to open cafés and “taverns” (actually motels) alongside each of the towers and gas stations, but that phase never reached fruition at most of the sites because of the Depression’s toll on the company. Barstow on Route 66 was the only place where a “tavern” was actually completed, and although Santa Maria was next in line for one—along with Capistrano and Visalia—none was ever built there.

Instead, private operators unaffiliated with the company—but eager to cash in on the “beacon” name and landmark—stepped into the void. An entrepreneur named Virgilio Del Porto advertised a competing gas station on the same stretch of road as offering “BEACON SERVICE,” even though he sold (at various times) Standard, Texaco, Economy, and St. Helen’s brands, but never Richfield.

The Beacon Motor Apartments (later renamed the Beacon Motel) went in across the road to offer lodging in lieu of Richfield’s shelved “tavern.” And in 1932, a Beacon Coffee Shop went up just north of the tower, the final element in the planned community Richfield itself had failed to produce.

In 1936, the state improved the highway between Orcutt and Santa Maria, widening it—although it remained just two lanes—and replacing the original pavement. About this time, development started creeping southward from town toward the beacon tower, a move accelerated by an oil strike in March of that same year. Before long, soaring wooden oil derricks nearly as tall as the Richfield tower began sprouting up on land across the highway from the beacon and nearby, competing for the traveler’s attention. One photograph shows half a dozen of them clustered across the road, behind the M&M Motel, which opened next to the Beacon Motel in 1939.

Oil rigs remained in the area into the 1970s, by which time Atlantic Oil had purchased Richfield and changed the name to ARCO.

That took place in 1966, and within a few years, the Richfield name had become obsolete. Already, during the 1950s, the original mission-style Richfield station had been replaced by a modern, generic “box” service station with mechanics’ bays and an overhang to shield motorists from the elements as they pumped their gas. Now, it was time for the iconic tower to go, as well: On March 2, 1971, a crane almost as tall as the tower itself lowered the steel-beamed behemoth to the ground intact.

It was later sold off as parts to an Oxnard milling company, which used its steel to build a gravel conveyor.

SPHINXES ON THE BEACH

In 1923, the legendary director Cecil B. DeMille checked in at the Santa Maria Inn on Broadway. He wasn’t the only Hollywood legend to stop at the luxury hotel: Douglas Fairbanks, Rudolph Valentino, and Charlie Chaplin all spent the night there, as did Bob Hope, Bing Crosby, Mary Pickford, William Randolph Hearst, and Joan Crawford. Stars adorn the doors to rooms where they stayed. Rumor even has it that Valentino’s ghost haunts one of the rooms.

Some of the hotel’s famous guests came to get away from it all, but DeMille was there on business. He was filming the next big Hollywood extravaganza, and although he was a long way from Hollywood, he’d originally planned to travel much farther afield for this portion of the movie: to Egypt.

That’s where The Ten Commandments was set, but even someone with as much clout as DeMille had to live with certain budget constraints, and Paramount wasn’t about to fly him and his crew all the way to the land of the pyramids for the sake of authenticity. We should note before continuing that the movie in question isn’t the Charlton Heston/Yul Brynner blockbuster—also directed by DeMille—which didn’t hit theaters until 33 years later. (Unlike the ’56 remake, which was set entirely in the biblical era, the second half of the original was set in the modern day).

The Santa Maria Inn on Broadway, an old alignment of U.S. 101, housed Cecil B. DeMille when he directed his first version of The Ten Commandments in 1923. Scenes were filmed at the nearby Guadalupe dunes.

This was still the era of silent films, but that didn’t mean DeMille’s production was small potatoes. Anything but.

Although DeMille had been thwarted in his request to film a portion of his movie in Egypt, that didn’t mean he was going to settle for half-measures when it came to realizing his vision. Craftsmen created a set modeled after the gates of Karnak—a famous temple complex that was, incidentally, a good 500 miles south of the Nile Delta, where the main action in the biblical narrative is supposed to have taken place. Historical concerns aside, the set was nothing if not spectacular. Rising 10 stories high and spanning 700 feet from end to end, it was fronted by giant statues and adorned with huge engravings of Egyptian charioteers. (Actual charioteers were used for the movie, too, with men from Battery E of the U.S. Cavalry filling those roles.)

The set featured 500 tons of plaster statuary, including four seated images of the pharaoh and no fewer than 21 sphinxes. The former were 35 feet tall, and the latter were so large their heads had to be removed before they could be shipped north from workshops in L.A. to the beach at Guadalupe, where the scenes were to be filmed. The sand dunes there, part of a 30-mile stretch that makes its way up the coast through Oceano to Pismo Beach, would serve as a stand-in for the Egyptian desert, with the Pacific Ocean playing the Red Sea.

On the set of The Ten Commandments, some of which lies buried beneath the shifting sands at Guadalupe even today. Collection of Cecilia de Mille Presley.

It was about a half-hour drive from the Santa Maria Inn, where DeMille was staying on the road that would become U.S. 101, west to the dunes, closer to today’s Highway 1. There, some 2,500 actors, extras, and crew members gathered in a temporary city of 600 tents called “Camp De Mille” that covered 24 square miles. Their task: to film scenes designed to evoke the grandeur of the biblical narrative. In one such scene, some 2,000 people and 4,000 animals lined up in a procession against a backdrop of dunes and seashore—with the line holding formation all the way from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.

The San Luis Obispo Telegram reported that “one of the most impressive scenes, actors yesterday freely agreed, was the yoking of several hundred people to a huge vehicle on which was placed a sphinx.”

When filming wrapped up, the question arose of what to do with the mammoth sets. Hauling everything back where it came from would be too expensive, and then where could it be stored? On the other hand, DeMille didn’t want to simply leave it there, where some other filmmaker might run out and shoot scenes on his set—or, worse yet, make off with some of the statues. So, in a large-scale example of “if I can’t have it, nobody can,” DeMille told his crews to simply bury the whole thing. To put it another way, he was simply protecting his patent.

In effect, DeMille had left a buried treasure in Guadalupe for someone to find—an ancient Egyptian city that wasn’t ancient and wasn’t in Egypt.

He wrote in his autobiography: “If a thousand years from now archaeologists happen to dig beneath the sands of Guadalupe, I hope that they will not rush to print with the amazing news that Egyptian civilization extended all the way to the Pacific Coast.”

As it happened, though, it didn’t take a thousand years.

Over the next few decades, a group of eclectic bohemians, drifters, artists, and free spirits gravitated toward the dunes, where they lived in driftwood shacks, eating fish and Pismo clams. Some of the folks who ended up there were transients left homeless by the Depression who had nowhere else to go. Others were utopians who believed in the lost continent of Lemuria and eccentrics such as Gavin Arthur, grandson of President Chester A. Arthur, whose resume included forays into writing, acting, and astrology.

John Steinbeck, Ansel Adams, and Upton Sinclair all visited the community at one time or another, but the Dunites, as they were known, came and eventually went.

Storefronts on Los Berros Road (old U.S. 101) in Nipomo date back to the late 19th century.

Meanwhile, in 1956, DeMille remade The Ten Commandments with Heston in the role of Moses, Brynner as the pharaoh, and Henry Wilcoxon as captain of the pharaoh’s guard. Wilcoxon, who also served as associate producer for the film, had been an A-list star in the 1930s, playing Marc Antony opposite Claudette Colbert in Cleopatra and Richard the Lion-Hearted in The Crusades. Both were DeMille films, and although the second was a box-office flop that knocked Wilcoxon off that A-list, DeMille tapped him for a series of projects in the 1950s that included the new Ten Commandments.

Henry Wilcoxon wasn’t involved in the original version of the movie—which was filmed eight years before he made his acting debut—but a cousin of his, Larry Wilcoxon, was … a long time after the fact.

The younger man, an archaeologist at UC Santa Barbara, had been hired by an oil company that wanted to drill out on the dunes. But in the course of conducting his studies there in 1977, he stumbled upon something else:

“We essentially discovered what was left of the movie set,” he told a reporter in 1984, describing it as “one of the last of the great movie sets left from that era” and estimating that as many as 16 of the sphinxes from the original film might be buried there.

But it would cost an estimated $50,000 to dig up the “lost city,” and despite media coverage from the likes of NBC Nightly News and People Magazine, the treasure hunters raised less than a quarter of what they needed over the next decade—enough to do a high-tech search beneath the sands and some preliminary survey work. An environmental roadblock emerged, as well: Because the dunes were home to the western snowy plover, listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act, special permits were needed to do any kind of work there.

A limited excavation in 1990 turned up such things as cough syrup bottles and tobacco tins, but it wasn’t until 2012 that more extensive work turned up large-scale finds from the buried set itself. Archaeologists uncovered the head of a sphinx they said was about the size of a pool table, and the wind that spreads the shifting sands across the seashore helped uncover the body of another sphinx. One of the sphinxes discovered at the site was still in just about the same place it had been during filming.

These days, some of the artifacts from the set are on display at the Dunes Center in Guadalupe, and work continues to excavate more of the set that DeMille thought might remain buried for a millennium.

It isn’t quite King Tut’s tomb, but it’s about as close to ancient Egypt as most motorists on U.S. 101 are ever going to get.

When you leave Santa Maria, the landscape changes: The flat, agrarian valley gives way gradually to rolling hills and an ocean view.

If you exit Santa Maria at Thompson Avenue heading north, you’ll be on the Old 101 for several miles through Nipomo. This section of road, which served as the highway alignment between 1930 and 1958, runs parallel to the current highway, a little to the east. The Nipomo Barber Shop, constructed in 1886, is still standing, right next to the general store, which was built eight years earlier.

North of town, the old alignment crosses back under the present highway at Los Berros Road. A still-older, pre-1930 version of the road veers north just after the underpass onto Quailwood Lane, which today is just a short spur that crosses an old bridge onto private land. There’s another short strip of the old road a little farther north at Hemi Road, which is the next exit, and still another at Tower Grove Drive.

Entering Arroyo Grande, the old highway diverges from the new once again at Traffic Way, which takes you past a series of businesses that date from the 1930s to the ’50s. Among the oldest is a 1930s-era gas station that’s been converted into Rod’s Auto Body. The original alignment continued up Bridge Street across a 1909 bridge to Branch, at which point travelers made a 90-degree left turn back west and (across the current freeway) north again on El Camino Real. In 1932, though, a short, gently curving bypass was built across a new bridge at Arroyo Creek, eliminating the Bridge-to-Branch-and-backagain portion of the route.

On El Camino Real, you’ll pass Francisco’s Country Kitchen, which you might recognize from the architecture as an old Sambo’s Pancake House.

Once you hit Pismo Beach, the oldest alignment of state Route 2—before it was designated U.S. 101—took an angular detour to the northeast on a narrow little drive called Frady Lane, then crossed Pismo Creek on an old bridge that dates back to 1912. The steel bridge is still there, but it’s closed now, so you can’t drive across it to the other side, where the route continued on Bello Street until it merged with Price Street at the north end of town.

If you travel up Bello today, you’ll pass a series of small, blue gable-roofed apartments as you head in toward town from the old steel bridge. The structures are obviously an old auto court that probably dated from before 1925, when the route was shifted away from Bello and west down Ocean View Avenue to Price Street, where you’d turn north again. Price Street through town remained the route’s alignment from then until 1956, when the current freeway bypass opened.

State Route 1 runs parallel to 101 through Pismo, a block west of Price Street, then merges with the federal highway at the north end of town, and the two highways share the same road from there to San Luis Obispo. Before the freeway went in, that road was Shell Beach Road through Shell Beach.

To stay on the old highway, turn west at Avila Beach Drive, then immediately north on Ontario Road, which will take you up to the south end of San Luis Obispo, crossing under the modern freeway and becoming Higuera Street. A very old alignment of the route—dating to the 1910s or early ’20s—runs on concrete between Higuera and the freeway. To find it, turn left at the distinctive white Pereira Octagon Barn and then south on the old road, which will take you across an old bridge before the pavement ends a few hundred feet farther on.

Francisco’s Country Kitchen is an old Sambo’s Restaurant that survives along Business 101 in Arroyo Grande.

The Octagon Barn itself is a notable feature of the old highway. The 5,000-square-foot structure was built in 1906 as part of a dairy farm and was used to house beef cattle beginning around 1950. Although the design was popular in the Midwest, the barn is the only one of its kind on the Central Coast. It was in danger of collapsing in the late 20th century: Its structure was sagging and its shingles were coming apart in 1997 when a 15-year restoration project began that succeeded in rescuing it. The barn was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2014.

Another barn on Higuera dating to the same era, on the Long-Bonetti Ranch just past Tank Farm Road, was on the verge of being torn down as of this writing. Developers were in the process of converting the site into a retail hub. And while the ranch house on the property, built in 1908, was to be preserved—and reborn as a restaurant—plans called for the demolition of the rickety old wooden barn.

This 1915 bridge is closed to traffic these days, but it once ferried drivers along an old and not-very-direct highway route through Pismo Beach.

The old highway continues on Higuera, past some vintage highway businesses. A keen eye will spot a couple of old motels on the east side of the road, and be sure to check out the old 1930s-era Texaco station at the intersection of Pacific Street; as of 2016, it was operating as a wine and beer shop called (appropriately) the Station. Just before you get there, take a detour left on Bianchi Lane, which crosses San Luis Obispo Creek on a 1905 bridge. It may not have been part of the original state route, but the age of the bridge makes it worth a look.

From there, the old highway alignment curved northeast through the heart of town on Marsh Street before jogging left briefly on Santa Rosa Street. If you continue on Santa Rosa, you’ll be on State Route 1, but to stay on the Old 101, turn right again in just a couple of blocks onto Monterey Street, which was the old highway through the remainder of town. At the northeast end of the strip is a series of motels, culminating in the historic 1925 Motel Inn, the last structure on Monterey before it rejoins the modern freeway.

The Station on Higuera Street, an old 101 alignment in San Luis Obispo, sold gas once upon a time; later, it sold wine, instead.