THE SALINAS VALLEY ROAD

When you hit the Cuesta Grade, it’s like hitting a wall that separated one world from another. To the south are verdant, rolling hills rising gently above inland valleys that open out onto the blue Pacific. To the north, on the other side of that wall, is the Salinas Valley, a flat and often dry agricultural plain; the Salinas river at its center runs between the Santa Lucia Range on the west and the Diablo Range to the east.

That wall was, to travelers of old, a formidable obstacle. Today’s U.S. 101 ascends a steep, seven percent grade, hugging the hillsides to the east, well above the floor of a narrow canyon. The old alignment entered that canyon at its south end along the old Stage Coach Road. You can still walk that section of road for a short distance, staring up at the imposing retaining wall built to keep the modern highway in place.

You can also continue on the State Coach Road over a distance of three or four miles until it spits you back onto the highway near the summit. Also known as the Padre Trail, it’s the oldest route through the narrow pass, heir to an 18th century dirt road that carried travelers between the San Luis Obispo de Tolosa mission to the south and San Miguel Arcángel mission to the north.

A horseshoe curve on the old concrete alignment of U.S. 101 traverses the narrow Cuesta Pass north of San Luis Obispo on what is now private land. This photo was taken from the modern alignment, which lies at a higher elevation to the east.

The old road between San Luis Obispo and Santa Margarita is seen in this pre-1920 photo. © California Department of Transportation, all rights reserved. Used with permission.

Old 101, meanwhile, veers off to the right, but you can only go so far before you come to a gate that bars your path onto what is now private land. Beyond that gate, the narrow concrete road ascends the canyon’s eastern flank via a horseshoe curve—still visible from the current freeway, especially to southbound traffic. The ribbon of concrete winds its way around three-quarters of a solitary hill before intersecting the modern road and crossing it, climbing farther up the hillside before disappearing into the underbrush. Before an upgrade in 1937, this section of highway had 71 curves; afterward, that number was reduced to a dozen.

“La Cuesta, the steep and tortuous grade that since the days of the Franciscan friars has been the bogey of travelers on El Camino Real, no longer will impede the flow of motor vehicle traffic over The King’s Highway,” engineer Lester H. Gibson exulted.

It was the latest, if not the last, in a series of improvements dating back to 1876, when the first upgrades to the old trail were made using $20,000 in bonds. A road of gravel and oil more suited to automobiles replaced it in 1915, and a concrete road was installed seven years later. Still, the circuitous route created a bottleneck over the grade for travelers midway between Los Angeles and San Francisco, and the state dedicated more than $1 million to construction of the four-lane highway that took its place.

Before that, Gibson wrote, “it was a frequent sight to observe a line of 20 or more automobiles creeping along behind a large truck throughout their crossing of Cuesta.”

A short section of roadway called Cuesta Springs Road coming down out of the pass northbound is another section of the old highway, which followed the current route to the intersection with State Route 58. There, it turned east along the state highway, making its way through the center of Santa Margarita in a route that would later be bypassed by the current 101 alignment.

Old West-style architecture in central Santa Margarita, north of the Cuesta Pass.

This old route can still be driven today.

Santa Margarita, which has the look of an old Western town, is one of those almost-boomtowns that never quite made city status. It was a hopping highway stop in the roaring twenties, when it boasted six gas stations, pool halls, restaurants, bars, and even a couple of baseball teams—one made up of ranch workers from the surrounding area and the other of Southern Pacific Railroad workers.

But the Depression took its toll, and fewer than 300 people lived there in 1939. Two years later, the government confiscated ranch land to build a reservoir—Santa Margarita Lake—to provide water for Camp San Luis Obispo, original home to the California National Guard. Any hopes for a substantial rebound were dashed when the new 101 freeway bypassed the town in 1956, and six decades later, the population was still less than 1,300.

The old road leaves State Route 58 at the east end of town and curves northward again along El Camino Real, a two-lane road that parallels the rail line as it stretches out across a lazy flatland of grasses dotted by oak trees here and there. Eight miles up the road, the old highway reaches Atascadero, paralleling the freeway through town until it rejoins the current alignment at the city’s north end.

Atascadero was founded in 1913 by a magazine publisher named Edward Gardner Lewis, who bought 23,000 acres and envisioned a utopian colony there (you’ll still see the word “colony” used at various spots in town). The first “homes” in the new colony were actually tents, pitched by homesteaders who came from across the country and waited while permanent housing was constructed. The Atascadero Printery, a brick building that still stands but was boarded up after an earthquake in 2003, published the first edition of the Atascadero News in 1916. It’s located just two blocks east of El Camino Real, on Olmeda Avenue.

On the old highway itself, you’ll pass the Carlton Hotel near the center of town. It opened just a month after the stock market crash of 1929 ushered in the Great Depression and played host to the likes of Bette Davis, Jack Benny, Fred MacMurray, Ralph Bellamy, and Dick Powell. Despite the hard times, the Annex—as it was originally called—attracted J. C. Penney, Safeway, and Sprouse-Reitz to open retail outlets on its main floor.

The Carlton Hotel is the most distinctive feature of the skyline in Atascadero, where the old 101 Alignment, El Camino Real, parallels the modern freeway.

Its name and ownership changed shortly after that to the Hotel Halfway and Coffee Shop, then again in 1931 when new owners adopted the current name in an attempt to play off the East Coast cachet it afforded them. Another owner added the distinctive clock tower in 1952, and the hotel went downhill over the next several decades, being converted into a senior housing complex and subsequently lying vacant for several years. Recent renovations, however, have restored it, and it opened for business as a hotel once again.

More affordable overnight stays could be had near the south end of town at the Beautysleep Motel, which dates to at least the 1940s and remained in business at this writing as a Mexican restaurant and apartments. Closer to the center of town was the Atascadero Motor Lodge, which originally consisted of cabins but was later remodeled to become a two-story motel and renamed the Rancho Tee. The distinctive golf ball atop the sign was hard to miss as you passed through town. It’s a long tee shot to the nearest fairway, though: The Chalk Mountain Golf Course is more than a mile south of the motel.

As it turns out, there used to be a golf course right behind the Rancho Tee. Bing Crosby led a parade of famous stars out onto the course in the summer of 1944 to boost the war bond campaign. One Atascadero resident remembered there was a green right behind the motel, and an errant tee shot could send the ball flying out onto El Camino Real (or, presumably, through a window at the motel!). The golf course was scaled back to nine holes in the 1960s and eventually closed. A large, modern movie theater complex was built where part of it had once been.

The Rancho Tee survived a bit longer, but as of 2017, a large red banner online labeled the place permanently closed.

The name “Atascadero,” incidentally, comes from the Spanish word for a bog—not a particularly romantic designation. More like a place to get stuck. TV producer Garry Marshall got stuck there once when his car broke down, but the incident served as the inspiration for something that really was romantic: a character named Pinky Tuscadero, whom Marshall introduced as the girlfriend of Arthur “Fonzie” Fonzarelli on the 1970s hit sitcom Happy Days.

This now-closed Chevron station operated from the early 1940s in Templeton.

Six miles north of Atascadero, the old highway reappears briefly through Templeton as Main Street. Look for sections of old concrete near the south end of Main and near the Legion Hall, just north of Templeton High School. A couple of old gas stations can be found off the old highway, as well: an abandoned 1940s-era Chevron station at 8th Street on the east side, and a smaller stop—converted into a fast-food joint called the Burger Station—on the opposite side of the road a block farther north.

Another sight worth seeing: a funky larger-than-life milk bottle, once used to promote the Rossi Dairy, that was partly overgrown by a large tree, off Rossi Road at the south end of town (this is on the west side of the freeway, opposite Main Street, so you’ll have to take the Vineyard Road exit and double back south in order to see it).

At the north end of Templeton, Main Street crosses the freeway and continues north as Theatre Drive—named for the old Oaks Drive-In that stood just south of the junction with State Route 46, not far from the old Richfield Beacon station. The theater opened in 1950, a year after the River Lodge Motel was built on the north side of 46. That motel, the latest in modern lodging when it was built, was still in business more than six decades later. The theater, however, was long gone, a dream that died with the era of the drive-in. Original owner Al Stanford, who opened the theater after selling stock to 15 local businessmen and farmers, kept the dream alive for 27 years before selling the theater; it was eventually abandoned and torn down in 1995 to make way for a Target store.

Continuing north to Paso Robles, you’ll find one of the most well-preserved sections of Old 101 in the form of Spring Street, which takes you off and modern bypass and straight through town. A few of the old motels remain along the route, notably the Farmhouse Motel at the south end of town, which dates to the late 1930s and still sports a distinctive neon sign. The Melody Ranch Motel farther north was built in the mid-1950s, and other roadside inns still visible include a TraveLodge that dates to the late ’40s, the Avalon Motel from the same period, and the Town House Motel from 1959.

The River Lodge Motel at the south end of Paso Robles serves travelers at the junction of U.S. 101 and State Route 46.

The 21st Street Drive-In and Foster’s Freeze are surviving remnants of an era when “drive-in” referred to meals as much as to movies, and the 1941 Fox Theatre (which opened as the Hi-Ho) still stands—although it’s closed as of this writing.

North of Paso Robles, the old road continues for a stretch as Monterey Road, and you can see some sections of the old concrete highway if you know where to look.

North of Paso, the highway heads through rural lands, and you’ll have to get off the modern highway to see most of the towns along the way. Built along old alignments, these small communities seem to be almost withering away in the summer heat, dusty towns on what was once the beaten path but which now lie all but forgotten and, in a few cases, nearly abandoned away from the current flow of traffic.

The first of these is San Miguel, home of the 16th mission to be built along old El Camino Real (in 1797). If you get off the highway on Mission Street heading north, you’ll be on the old highway, and you’ll see a three-story stand-alone bell tower directly in front of you as you exit the off-ramp. Take your first right, and you’ll be on the oldest section of highway in this area: concrete that now serves as a driveway to the Rios Caledonia Adobe. Built in 1835 by Native Americans, the adobe was once part of the mission property. The short drive, lined on both sides by shade trees, will give you an idea of what the old road was like in its earliest incarnation.

A building on the southwest corner of 12th Street, a business called the Coffee Station at this writing, is a pre-1940 Union Oil gas station; the building behind it was the garage.

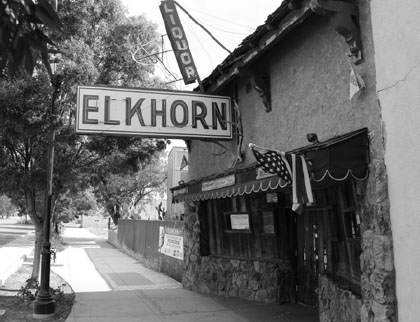

Less than a block farther north on the same side of the street, you’ll come to the Elkhorn Bar, the second-oldest watering hole in the state of California, dating back all the way to December 5, 1853. It was originally part of a tent city across from the mission, “at the site of an adobe frequented by Frank and Jesse James”—at least according to a plaque near the entrance. The original saloon burned down in 1925, after which it reopened at its current location.

The Elkhorn has a long and colorful history in San Miguel.

Prohibition was in effect, but the bar remained open—customers just had to enter from the alley around back. The “front” to the place was a barbershop and candy store, and shipments of booze were lowered into the cellar through a trapdoor in the barbershop, then carried to the bar upstairs. The place got even more popular once Prohibition ended, especially during World War II, when the town became a gathering spot for troops stationed at nearby Camp Roberts. There were more than a dozen bars at that time in a once-sleepy town where the population had been just 300 a few years earlier.

Today, the establishment embraces its Old West heritage, with a woodstove and gun racks inside. Above the door is a more recent but still vintage neon sign featuring the standard, iconic tipped martini glass.

Next stop on the drive north is Bradley, which you can reach by exiting at Bradley Road and driving along the old alignment through town. It was bypassed by the current highway during the 1950s, and the town went rapidly downhill after that. There isn’t much there now, and the population as of 2010 was shy of 100 people—less than what it was in the 1930s, before which an even older alignment took travelers down Meadow Street, south on Pleyto for a couple of blocks through the heart of town, and then west again on Dixie Street and across the Salinas River on a bridge that was torn down in 1933 and replaced with the current structure on Bradley Road. The concrete supports of the old bridge are still visible.

Many of the town’s old commercial buildings are gone now, but a few remain. Notable among them is an old service station with a few pumps dating from the 1950s still out front at Pleyto and Bradley. A block farther on, at Monterey, you can see the remnants of a pair of old motels: the Allen and the Sea Plane Inn.

The owner of the Sea Plane Inn, which dates back a century in Bradley, has amassed an odd and varied assortment of vintage collectibles large and small, including old gas pumps and (appropriately) a propeller.

The latter, on your right, is particularly interesting. Henry Veach bought out another business in town and moved it to its present location in 1916. He set up shop as a grocery store and gas station, but it was also known as “the Zoo” because Veach had, well, a zoo there that featured coyotes, foxes, deer, monkeys, alligators, and—the star attraction—a bear. You didn’t want to get too close to the bear’s cage, which is why Veach was rumored to have hidden his liquor stash there during Prohibition.

After you leave Bradley, keep going up the freeway until you hit Cattlemen Road, then turn east onto another section of the old alignment that will take you through San Ardo. This section of old road was 101 more recently than most: It was only bypassed in 1971. An older alignment ran parallel along Jolon Road to Main Street, which took you north to hook up with Cattlemen. An older trestle bridge carried Jolon across the Salinas River, but as with the old Bradley Bridge, all that remains are concrete supports, some still visible from the newer Cattlemen Bridge, which dates to 1930.

The fact that Cattlemen itself was originally a bypass is easy to tell from its long, gentle curve, which skirts the old downtown as its eastward heading changes to a north-south alignment along the railroad tracks.

One of the oddest sights in San Ardo is an old Shell gas station sign at the north end of this curve. It drew motorists to an old, single-bay station that was probably the “last chance” to get gas for a few miles. It stood next to the old Evergreen Camp restaurant, which was later replaced by the Evergreen Park (for mobile homes). There are still a lot of trees there, some of which partially obscure the Shell sign itself. The sign is interesting because it appears somewhat similar to the highway signs that tower beside modern freeways, but it’s much lower to the ground, perhaps just 15 feet tall.

There’s not much to see for the next several miles along Cattlemen, except the railroad tracks on the east and rows of crops on either side. You’ll pass the abandoned buildings of an old labor camp on the west side of the road before you get to San Lucas, after which Cattlemen again joins the modern highway route. An old cattle ranching town, it was once known for raising fine thoroughbred horses, but today it’s showing its age.

Before 1930, the highway went through town on Main Street, just east of the rail line; afterward, it ran on the other side of the tracks as Cattlemen. The most distinctive feature is three connected grain cylinders that rise above the highway at the south end of town, easily the loftiest structure on the landscape.

This Shell sign on Cattlemen Road at the north end of San Ardo is largely obscured by trees these days. The service station itself closed long ago.

The King City Auto Camp offered Salinas Valley travelers a place to spend the night, and fill up their tanks with Shell gasoline. Collection of Michael Semas.

The heart of town was, for many years, the Bunte General Store on Main Street, a red, wooden structure built in 1886. The store’s name dates back to Sam D. and H. D. Bunte, who operated the store until 1917. At one time, it sold “Big D” gasoline and housed an impressive collection of antiques. But the store burned down in July 2006 in a fire which investigators suspected was arson that spread from a dumpster next to the building. Nearby residences were spared, but the store was destroyed.

The Pit Stop is still there on Cattlemen Road: The building (which is a lot taller in front than it is in the back) was built in the 1930s and used to include a gas station, though the pumps are long since gone. Today it’s a small diner.

From San Lucas, the modern highway—this section was built in 1962—heads north to King City, where the old alignment veers east from the current highway as First Street, then heads back toward it along Broadway. The First Street bridge over San Lorenzo Creek dates to 1924, when the section of road on either side was still unpaved.

The old highway next appears in Greenfield as El Camino Real, which was the main route until the bypass was finished in 1966. A short section of an even older alignment can be found at the north end of town, where a brief stretch of concrete is visible near Cypress Avenue just west of El Camino Real. As you enter the older section of town from the south, look on your right for a sign sticking up from the top of a blue gabled roof. From the north side, you can see the remnants of old Richfield lettering on the sign—at least you could as of this writing.

Once you leave Greenfield, it’s on to Soledad, where you exit on Front Street, another old motel-and-gas-station row that’s a dead giveaway you’re entering another town along the highway.

Gonzales, the next town north, carries the old highway through town on Alta Street. At the north end of town, just before you rejoin the new highway, you’ll pass the abandoned Rincon Café on the right. It’s obviously been there (and closed) for a long time, but check out the distinctive step-pyramid design over the entrance. An attached garage would seem to indicate it was once a service station, as well.

It’s hard to tell what they served at the Rincon Café near Gonzales, but it’s safe to say there’s nothing but dust and weeds on the menu these days.

Old concrete, foreground, leads motorists up the San Juan Grade, a winding old alignment of U.S. 101 east of Salinas that was bypassed in the early 1930s and survives as a scenic mountain road.

Chualar, site of an old Richfield Beacon station, is the last stop before you get to Salinas. Then, if you want an adventure—and a scenic one at that—take the old San Juan Grade up over the mountains northeast of Salinas.

The original alignment followed Old Stage Road, which skirts the city limits to the east before veering off into the foothills, away from the current road. If it seems out of the way, it is: If the road kept going in that direction, it would deposit you in Modesto (or thereabouts). But that was the path the state highway commission settled on back in 1913, when it chose to route travelers over the San Juan Grade rather than on a course beside the Pajaro River via Watsonville.

The debate over the route pitted Salinas against Watsonville, and in the end, Salinas won the day.

Why choose the tortuous, narrow path across the mountains instead of the less encumbered riverside route?

For one thing, the former was a little more direct, at least in terms of mileage. Besides, when the decision was made, cars couldn’t have gone much faster on a straightaway than they could have over the mountains. They just didn’t have the horsepower. But perhaps the most important factor was money: According to a report in the Santa Cruz Evening News, “the banks of Salinas and Hollister showed their faith in the highway by taking up road bonds in the sum of $75,000.”

It was a decision they likely came to regret when cars started going faster but trucks continued to inch their way over the grade at a snail’s pace. This was, after all, the main thoroughfare between L.A. and San Francisco, and no matter how scenic the drive might have been, travelers had little patience, then as now, for spending an afternoon stuck behind a sluggish convoy on a twisting mountain road.

A highway department report written in 1931—barely a decade and a half after the San Juan Alignment opened—cut to the chase: The grade had become “increasingly exasperating” for motorists traveling between Los Angeles and the Bay Area. Although it had been “entirely adequate for the prevailing traffic” in 1915, “due to the tremendous increase in motor vehicular travel, this grade has been obsolete for several years. Because of the long grades, narrow roadway and sharp curves, it is now a bottle neck on the Coast Highway and the scene of many unfortunate accidents.”

So, the decision was made to forge a new alignment for U.S. 101 over flatter terrain, cutting more than a mile off the trip in the process. The million-dollar project, dubbed the Prunedale Cut-off, would cover just under 17 miles, and its highest point would be a mere 550 feet, barely half the altitude of the old grade. It’s the route still followed by U.S. 101 today.

One by-product of the change was to bypass San Juan Bautista, an old mission town on the original El Camino Real that lay three miles east of the new alignment. Motorists hoping to reach the town now had to leave the federal highway in order to do so. To help them find it, the highway department placed a small, freestanding bell tower surmounted by a cross at the turnoff—and the 1930s-era campanile is still visible today at the junction of U.S. 101 and State Route 156.

It’s still worthwhile to take the San Juan Grade north out of Salinas if you have some extra time for a scenic drive. Rolling foothills and shady stretches lined with trees will be your reward, along with some glimpses of old concrete from the original roadway. On the other side of the ridge, the road offers scenic views of the valley below before taking you down past rolling farmland and a couple of rectangular C-blocks. (These short concrete markers were placed along highway rights-of-way starting in 1914 and continuing, in some places, through the 1950s. If you look closely, you can find these two on the north side of the roadway as the land starts to level out.)

In short order, the old highway will deposit you in San Juan Bautista, traveling through town as 3rd Street just a block southwest of the old mission, where you’ll find a distinctive El Camino Real bell on the grounds. Many of the buildings lining the two-lane street would seem right at home on an Old West Hollywood set. Don’t blink, though. The business district is a mere ten blocks long.

Near the north end of town, the highway jogs right for two blocks, to First Street, then carries you out of this sleepy community (2016 population: 1,975) and off across rural flatland. You’ll rejoin the modern 101 alignment about three miles up the road.