Some of Shakespeare’s plays go in and out of fashion. It may take a landmark production or individual’s performance to bring a play back into vogue. The four great Tragedies are the most resilient (partly because they offer ‘star’ vehicles to actors) along with certain of the Comedies. Others (despite their remarkable qualities) will never be in the top ten for the theatre-going public, beloved as they may be among the literati: plays like Measure for Measure, Troilus and Cressida and Timon of Athens. Modern audiences can’t grapple with them; they are too ambivalent, brooding and unsettling—not a ‘feel-good’ night at the theatre.

The Histories need constant reinvestigation, especially here in Australia. Native Brits have a headstart because they own the content and know something of the territory. Even if they don’t know the history at least the place names are familiar.

For some Australians, still trying to overcome our ‘cultural cringe’ or disowning a heritage of monarchy and British imperialism, Shakespeare’s historical chronicles might be seen as irrelevant and resistible.

‘Oh, I can’t be doing with those plays!’ a lady said to me. ‘All those names and all those kings!’

But the Histories are about a lot more than kings and chronicles. They provide political commentary, satire and wry comedy. They have an epic sweep that can be viscerally exciting. They are about treachery, ambition, idealism and dirty deals. Above all, they are about family—fathers and sons, brothers and cousins, wives and lovers. They are packed with great characters, great scenes and great roles for actors. And, most importantly, they are packed with humanity. A production that is dry, pedantic, cold or overly intellectual will confirm an audience’s worst fears about history plays. Shakespeare’s Histories are emotionally driven: passion, rashness, hate and envy are things we can all relate to. And we can watch in sadness and in horror to see how these primal forces dictate men’s actions and shape the course of human affairs. And whether we’re talking about medieval England, twentieth-century Europe or contemporary Australia, the patterns and archetypes are disturbingly familiar.

Shakespeare’s tragic heroes exist on a higher plane. We can marvel at their sufferings but hardly expect to share their experiences. The people in his history plays inhabit a world much closer to our own. We know these people from everyday experience. The crimes they commit and the mistakes they make are the stuff of the daily press. Forget ‘all those names and all those kings’; Shakespeare’s Histories are relevant to us in a profound and satisfying way. It is the job of the actor and director to make that plain.

There are ten ‘history’ plays in all; that is, plays based on actual English history, starting with King John then skipping to Richard II. From here we run in an unbroken historical sequence through the reigns of Henry IV, Henry V, Henry VI, Edward IV and Richard III. There’s another small break, jumping over Henry VII, but we pick up again with Henry VIII (or All Is True), written by Shakespeare in collaboration with John Fletcher. It’s tempting to add Edward III to the top of the list. The authorship is disputed but Shakespeare may well have had a hand in it.

I have directed or acted in all of them except King John and Henry VIII. (I don’t know anybody else who’s been in those two either.)

Henry IV

I’m very attached to all of the Histories but my firm favourites are both the Henry IV plays. They should be seen more often, but I guess the sheer scale of them and the size of cast required puts them out of reach for a lot of theatre companies.

Their crowning glory is Falstaff. It’s the only major Shakespeare role I have not played and have a yearning for. But I’m apprehensive about it—I might be totally miscast. Along with Hamlet, Cleopatra and Rosalind, Falstaff is a character of such genius he seems to have invented himself. You can’t imagine how any author could have thought him up. It has often been remarked that he seems to have a life independent of the play. He has just dropped in, so to speak. Elizabeth I thought so too. According to legend she liked Falstaff so much she asked Shakespeare to write a play showing the fat knight in love—so Shakespeare whipped up Merry Wives of Windsor in a fortnight.

Falstaff is an uncanny mix of cunning and innocence, of largesse and self-interest. He is the father of mirth and carries laughter wherever he goes. Moreover, he realises that he is not only witty in himself but also the cause of wit in other men. Despite his grandiose swagger he has the human failings of gluttony, sloth and cowardice, with which we can all identify. He has a natural dignity that is never swamped by his utter shamelessness. Nothing can subdue his zest for life, and this is his greatest attribute.

We travel a long road with Falstaff and are privy to his many moods, including the pathos of old age and the pain of rejection. His wit has a quicksilver brilliance. He can be disarmingly shrewd and candid. But there is an overweening ambition to Falstaff, a monstrous gulf that cannot be filled. When he hears that the old king is dead and his protégé is now Harry V, he flourishes his fist in the face of all civil authority and invokes a vision of chaos and misrule:

Let us take any man’s horses: the laws of England are at my commandment,

Blessed are they that have been my friends;

And woe to my Lord Chief Justice!

Finally Falstaff has to go. But the Henry IV plays are stuffed with a multitude of great characters besides Falstaff. There is the enigmatic and fascinating Prince Hal, his low-life sidekicks Poins, Bardolph and Pistol; the fiery and glamorous Hotspur, the mad Welsh wizard Glendower, the deliciously observed Mistress Quickly and Doll Tearsheet, the quirky old country justices Shallow and Silence, the autocratic and guilt-ridden King Henry himself, along with a score of brilliant cameo sketches.

A whole nation is set before us like a vast Brueghel landscape, so populous, so detailed. From the cold and lonely court of Westminster we flee with Hal to the warm, riotous embrace of the Boar’s Head Tavern. We travel from the wild Welsh marches through the countryside of Shrewsbury with Henry’s army . . . We go from Northumberland’s castle in Warkworth to the streets of Cheapside and Eastcheap, to York and the Archbishop’s palace, through a forest in Yorkshire and to Justice Shallow’s farm in delightful Gloucestershire, where we come across the pathetic army conscripts Mouldy, Wart, Feeble and Bullcalf.

Shakespeare uses the polarities of the court and the tavern not only to show us the diversity of English life and society but to let the one comment on the other. At Westminster King Henry rules in bitter loneliness. In the tavern Falstaff is king, sitting on his throne with a cushion on his head in mockery of a crown, surrounded by mirth and ribaldry. He conducts a mock interview with his ‘son’, the prodigal Prince Harry—a travesty of the painful father/son reconciliation scenes to come.

In contrast to the japes of Hal and Falstaff we have the cold-blooded realpolitik of Hal’s sibling, Prince John of Lancaster. Having made a peace deal with the rebels, Prince John executes the lot of them with the pious exclamation, ‘God, and not we, hath safely fought today.’

Pragmatism runs in the family. On his deathbed Henry laments the fact that his kingdom is factious and rebellious. He shrewdly advises his eldest son to ‘busy giddy minds with foreign quarrels’, thereby setting the scene for a totally unjustified invasion of France and the creation of a cult of the national hero.

Prince Hal himself is the arch-pragmatist, which makes him easy to play because his motivation is unambiguous. But it can make him difficult to empathise with unless one offsets the ruthless pragmatism with some sterling virtues.

I played Prince Hal in a highly successful production at Sydney’s Nimrod Theatre in 1978. It was directed by Richard Wherrett with something resembling a medieval set and costumes. We combined the two parts of Henry IV into one fairly long evening accompanied by a ‘medieval banquet’ in the foyer during interval. Frank Wilson played a raffish Falstaff with a whiff of the Australian racetrack about him. I enjoyed our scenes together as Frank was a natural comedian and song-and-dance man. Comedy and pathos came easily to him, along with a natural insouciance.

Hal’s strategy is made clear right from the start. He has observed his father’s tactics and found them wanting. King Henry’s concept of kingship is aloofness:

By being seldom seen, I could not stir

But like a comet I was wondered at . . .

Hal, on the other hand, is determined to get to know his subjects and speak their language:

I am sworn brother to a leash of drawers [tavern waiters], and can call them all by their Christian names, as Tom, Dick and Francis . . . when I am king of England, I shall command all the good lads in Eastcheap.

This is a strategy he follows through when he is King, all the way to Agincourt. Before that famous battle he again calls his troupes by name—

Harry the king, Bedford and Exeter,

Warwick and Talbot, Salisbury and Gloucester

—and assures them that together they make up

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers.

Hal is an absolute master of spin and supremely conscious of the effect he is having. He is determined that in his youth he will be a popular scapegrace, one of the lads, but when the time comes to assume his kingly responsibilities, he will dump all his old companions and dazzle the world with his reformation:

So when this loose behaviour I throw off,

And pay the debt I never promised,

By how much better than my word I am

By so much shall I falsify men’s hopes;

And like bright metal on a sullen ground,

My reformation, glittering o’er my fault,

Shall show more goodly and attract more eyes

Than that which hath no foil to set it off.

I’ll so offend to make offence a skill,

Redeeming time when men least think I will.

This game plan is carried out with calculated efficiency: on the day of Hal’s coronation all his old companions are arrested and carted off into obscurity. This behaviour is chilling but is consistent with Hal’s subsequent behaviour.

So, in playing him what does the actor look for?

For a start, there is a vulnerability in Hal. He is the eldest son of an iron-willed autocrat with whom he has little in common. One can’t help but side with him when he seeks to let loose and have fun with his mates at the Boar’s Head. He desperately craves his father’s approval and admiration and is cut to the quick when the King sings the praises of Harry Percy, the gallant Hotspur:

I will redeem all this on Percy’s head,

And in the closing of some glorious day

Be bold to tell you that I am your son . . .

And that shall be the day, whene’er it lights,

That this same child of honour and renown,

This gallant Hotspur, this all-praised knight,

And your unthought-of Harry chance to meet.

It is easy for a young actor to identify with these aspects of Hal—the resentful teenager rebelling against an autocratic father yet desperately seeking his approval; what amounts to a sibling rivalry with the show pony Hotspur, and the desire to escape the close confines of stuffy respectability and sow a few wild oats. It seems to be the destined path for many a Prince of Wales.

There is a wit and ingenuity in Hal; there is a love of life and adventure and a good deal of generosity—when it suits him. He covers up for Falstaff in an embarrassing confrontation with the Sheriff and, despite the cruelty of his rejection of Falstaff, there is provision made for his future.

Hal has a sense of honour and is big enough to admire Hotspur’s qualities, yet one cannot afford to sentimentalise him or apologise for his ruthlessness. He is above all a realist—not altogether admirable but nor is he devious like his younger brother. When Falstaff challenges him, ‘Banish plump Jack, and banish all the world,’ Hal warns him: ‘I do. I will.’

For me the sustaining interest in Henry IV is the emotional triangle between Hal, his father and his surrogate father, Falstaff. The latter gives him the affection and companionship his real father denies him, but Hal is shrewd enough to recognise Falstaff’s self-interest and ambition. In spite of Falstaff’s enormous appeal he is a fraud, a liar and a user of people. He is quite brazen and unrepentant in his misuse of his office as a recruiting sergeant. He tries to enlist wealthy yeomen’s sons who will pay a bribe to be excused. The recruits he is left with are feeble and useless to the army, but Falstaff callously dismisses them as ‘food for powder; they’ll fill a pit as well as better’.

Hal is one of Shakespeare’s ‘new men’, whom he seems to regard with a mixture of fascination and distaste. They are creatures of the Renaissance, students of Machiavelli—shrewd, calculating and cold-hearted. At their best they are men like Hal and Falconbridge in King John. At their worst, Iago in Othello and King Lear’s Edmund. Macbeth’s Malcolm is one of them, Octavius in Julius Caesar another and so is Hamlet’s Young Fortinbras. They always come out on top but you wouldn’t necessarily want to get too close to them.

Despite the inevitability of the new men and the triumph of Elizabethan ‘policy’, one feels that a lot of Shakespeare’s sympathy and affection belongs to an older England, the carnival riot of Falstaff and chivalric flourishes of Hotspur. With the death of those two, the last vestiges of medieval England fade away.

Henry IV is an easily accessible play even though some of the prose vernacular is a little arcane. But it’s wonderful stuff, recorded with such accuracy. One of my favourite passages is often cut in production, for various reasons: to save time; to reduce cast size; and because it seems irrelevant to the action. But it’s a little window into London life as Shakespeare witnessed it. Two carriers are stabling their horses for the night and whingeing about the pub they are staying in:

[ACT II, Scene 1. Rochester. An inn yard]

Enter a Carrier with a lantern in his hand.

First Carrier: Heigh-ho! An it be not four by the day, I’ll be hanged. Charles’ wain is over the new chimney, and yet our horse not packed. What, ostler!

Ostler: [Within] Anon, anon.

First Carrier: I prithee, Tom, beat Cut’s saddle, put a few flocks in the point; the poor jade is wrung in the withers out of all cess.

Enter another Carrier.

Second Carrier: Peas and beans are as dank here as a dog, and that is the next way to give poor jades the bots. This house is turned upside down since Robin Ostler died.

First Carrier: Poor fellow never joyed since the price of oats rose; it was the death of him.

Second Carrier: I think this be the most villainous house in all London road for fleas: I am stung like a tench.

First Carrier: Like a tench? By the mass, there is ne’er a king christen could be better bit than I have been since the first cock.

Second Carrier: Why, they will allow us ne’er a jordan, and then we leak in your chimney, and your chamber-lye breeds fleas like a loach.

First Carrier: What, ostler! Come away and be hanged! Come away!

Second Carrier: I have a gammon of bacon and two razes of ginger, to be delivered as far as Charing Cross.

First Carrier: God’s body! The turkeys in my pannier are quite starved. What, ostler! A plague on thee, hast thou never an eye in thy head? Canst not hear? And ’twere not as good deed as drink to break the pate on thee, I am a very villain. Come, and be hanged! Hast no faith in thee?

I directed Henry IV for Bell Shakespeare in 1998 and it was one of the most personally satisfying productions I have done. As with the Nimrod production of 1978 I conflated the two plays into one evening, sacrificing a large chunk of Part 2, which deals with a second rebellion being quelled by John of Lancaster. This was because I wanted to concentrate on that intimate three-way struggle between Hal, Falstaff and King Henry. It’s nothing new: Orson Welles created a notable version along the same lines. He played Falstaff as well as directing, and after the successful stage version made the film Chimes at Midnight.

But whereas both Welles and Richard Wherrett in his Nimrod production had gone for a medieval look, I wanted to bring the plays sharply into focus as a comment on contemporary Britain and examine Australian attitudes to monarchy, war and family.

Justin Kurzel’s set featured a steep cement ramp with piles of furniture strewn either side, as if a highway had been driven through a housing estate, sweeping aside the people. Industrial wire gates could seal off the ramp when necessary. Furniture was scavenged from the rubble when required but most of the props were mimed, and minimal. Clothes denoted both rank and location: the tavern habitués wore second-hand cast-offs, the court three-piece suits and the northern rebels fur-lined coats. Alan John’s music score was heavy rock (four of the cast played electric guitar) which could accommodate war-like anthems. Hal and Hotspur were locked inside a wire cage for their knife fight while their supporters bashed on the wire and egged them on with football-hooligan chants. The battle scenes were ugly brawls stripped of any semblance of chivalry.

The ironic tone of the production is probably best illustrated by the treatment of King Henry’s soliloquy in Act III, Scene 1. He bemoans the burden of kingship and envies the lot of the simple citizen. Instead of keeping Henry safely closeted in his royal apartments, I brought him out into the street. The stage was littered with bodies huddled under blankets or taking refuge in cardboard boxes, coughing, wheezing and moaning in their sleep, just as I’ve seen them under the bridges along South Bank in London. The King, warmly wrapped in his overcoat and muffler, wandered among them, commenting on their good fortune:

Then, happy low, lie down;

Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown.

I think the production said a lot about Australian attitudes not only to the monarchy and the English class system, but about war, violence, mateship, sexism and what constitutes ‘honour’.

John Gaden’s Falstaff could be sly and lewd yet move with ease up and down the social scale, while Joel Edgerton’s Hal endowed the troubled teenager with a fundamental decency.

Henry V

This is probably the play that opened the Globe Theatre in 1599. Shakespeare finished it in a hurry amid rumours that the Master of the Revels would soon prohibit all re-enactments of English history on the stage. Where the preceding plays are a sprawling human epic, Henry V is more like a pageant and is somewhat harder to bring off today. But that’s a recent phenomenon: the play was enormously popular throughout the nineteenth century (in England at least), representing the very essence of Empire and ‘Rule Britannia’. The play’s popularity peaked again during the outbursts of patriotic fervour that accompanied both World Wars.

But war has begun to look decidedly less glamorous in the wake of the Holocaust and subsequent conflicts, including Vietnam and Iraq, and other atrocities around the globe. We can no longer be fobbed off with patriotic headlines and spin in the daily newspapers but have immediate footage beamed into our living rooms.

Laurence Olivier was withdrawn from the British Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm to make a propaganda movie in 1943. It was to be a patriotic morale booster for troops and civilians alike. Olivier chose Henry V. The story he told goes like this:

Henry V is a dashing young English king who is insulted by the French crown prince. Henry V responds by invading France to reclaim territories that are rightly his. After a series of quick victories he finds himself confronted by a huge French army with his own greatly outnumbered. Despite this, he rallies his troops and scores a stunning victory at Agincourt. He woos and marries the beautiful French princess and all ends in peace and happiness.

To ensure the film’s wide appeal, Olivier made it extremely picturesque and escapist. The charming landscapes were based on the gorgeous medieval miniatures in Les très riches heures du Duc de Berry, a Book of Hours illustrated by Peter and Paul de Limbourg. To overcome the slight embarrassment that the enemy was not German but French (Britain’s ally), the French king was made into a harmless old duffer and the Constable of France a warmly attractive ‘good sport’. The Battle of Agincourt was a colourful and bloodless affair—a bit like a footy grand final—and to distance the play still further from uncomfortable reality, it was set within the framework of a performance at the Globe Theatre. These were just a bunch of actors ‘putting on a play’. As a populist morale booster the film was a great success, but as a serious interpretation of Shakespeare’s play there was a lot missing. Kenneth Branagh’s film version filled in some of the gaps: his Battle of Agincourt was a grisly affair, as was his capture of Harfleur. He included some of Henry’s ruthless acts (which Olivier chose to omit), such as the executions of his treacherous nobles and his old mate Bardolph. Both versions chose to overlook Henry’s slaughter of his French prisoners in their desire to keep the eponymous hero as attractive as possible.

Now let’s look at an alternative reading of the story as Shakespeare tells it:

A new young king inherits from his usurper father a kingdom that is factious and rebellious. His legitimacy as king is questionable. With his dying breath the father advises the son to ‘giddy busy minds with foreign quarrels’; a patriotic war will deflect rebellion, unite the country and make the new king a national hero. English pride will be restored by the reclaiming of territories held by the French. The new King Henry bullies and blackmails the Church into sanctioning his cause. If the bishops refuse:

We lose the better half of our possession;

For all the temporal lands which men devout

By testament have given to the Church

Would they strip from us.

With the Church’s blessing Henry undertakes a war of invasion, using as a pretext a minor insult from the French Dauphin. When Harfleur resists his attack he threatens them:

. . . why, in a moment look to see

The blind and bloody soldier with foul hand

Defile the locks of your shrill-shrieking daughters;

Your fathers taken by the silver beards,

And their most reverend heads dashed to the walls;

Your naked infants spitted upon pikes,

Whiles the mad mothers with their howls confused

Do break the clouds, as did the wives of Jewry

At Herod’s bloody-hunting slaughtermen.

What say you? Will you yield, and this avoid?

Or, guilty in defence, be thus destroyed?

Olivier and Branagh chose to leave that out too. It is somewhat at odds with Henry’s pious statement earlier on: ‘We are no tyrant, but a Christian King.’

Shakespeare’s Henry sets a trap for three of his nobles who are planning to assassinate him. He refuses to show them mercy, nor is he merciful to poor old Bardolph, who is hanged for robbing a church. But his most heinous act takes place during the Battle of Agincourt. Thousands of French nobles have surrendered and are rounded up as prisoners. The scattered French forces regroup and threaten to attack Henry’s rear. He cannot fight this rearguard and risk the prisoners’ escape, so he orders ‘every soldier kill his prisoners!’ Even by medieval standards this was a war crime against all rules of chivalry. It was also unpopular with the soldiers, who could expect a princely ransom for each prisoner—dead they were worth nothing. Tactically speaking maybe Henry was right, but it leaves an ugly stain on his reputation, which is why most productions skate over the moment or omit it altogether.

In my Bell Shakespeare production of 1999 I chose instead to highlight the incident. When Henry gave the order, his generals stood in shocked silence and would not move. Henry took out his revolver, pointed it at an officer’s head and commanded, ‘Give the word through.’ The officer reluctantly obeyed.

Why did Shakespeare include the incident? Because he wanted to show us all sides of war. Henry’s motivation in going to war is made very clear, as are the motives of the common soldiers and camp followers. Pistol sums it up best:

. . . I shall sutler [providore] be

Unto the camp, and profits will accrue . . .

Let us to France, like horse-leeches, my boys,

To suck, to suck, the very blood to suck!

The yeomen’s, farmers’ and peasants’ sons drafted into the army have no illusions about the glamour of war as one of them says:

But if the cause be not good, the King himself hath a heavy reckoning to make, when all those legs and arms and heads, chopped off in a battle, shall join together at the latter day and cry all, ‘We died at such a place,’ some swearing, some crying for a surgeon, some upon their wives left poor behind them, some upon the debts they owe, some upon their children rawly left. I am afeard there are few die well that die in a battle; for how can they charitably dispose of anything when blood is their argument? Now, if these men do not die well, it will be a black matter for the King that led them to it . . .

This is a stinging rebuke to the King and the last thing he wants to hear the night before the battle. But Shakespeare places it very deliberately.

In case we haven’t got the point about Henry’s ruthlessness, Gower and Fluellen enter to debate the King’s action, with Gower declaring:

. . . the King most worthily hath caused every soldier to cut his prisoner’s throat. O, ’tis a gallant king!

As if that were not irony enough, Fluellen enthusiastically agrees, comparing Harry to Alexander the Great, but with a sting:

Fluellen: . . . as Alexander killed his friend Cleitus, being in his ales and his cups, so also Harry Monmouth, being in his right wits and good judgements, turned away the fat knight with the great belly doublet—he was full of jests and gipes, and knaveries and mocks; I have forgot his name.

Gower: Sir John Falstaff.

Fluellen: That is he: I’ll tell you there is good men porn at Monmouth.

It is an odd moment, at the height of Henry’s glorious victory, for us to be reminded of his heartlessness in banishing Falstaff. The fat knight dies again before our eyes and the last glimmering rays of Old England die with him.

Just before Henry forces the French king to surrender his daughter in marriage, the Duke of Burgundy gives an eloquent and moving description of the devastated French landscape, bringing the horrors of war vividly into focus and, to drive a final nail into the coffin of chivalry, the epilogue reminds us that the whole campaign was fought in vain: following Henry’s death a few years later, the French regained all their territories and England collapsed into the bloody epoch known as the Wars of the Roses . . . Curtain.

How are we meant to react? Are we meant to cheer for Harry, England and Saint George? Are we meant to applaud the number of the slaughtered French? To be tickled by the forced marriage of the young princess? Many directors these days set out to present Henry V as an anti-war play. This takes considerable dexterity and demands as much fiddling with the text as it does to present it as a pro-war play. The text defeats you: there is too strong a presence of genuine heroics and celebration. The only realistic approach is to regard the play as neither anti- nor pro-war but about war in all its aspects; and, much as we may dislike it, there are aspects of war, while it is happening, that many people respond to with enthusiasm.

We must also take on board the fact that warfare is a different business today to what it was in Shakespeare’s day. From the time of Homer up until the early twentieth century, poets have sung of ‘the pride, pomp and circumstance of glorious war’—as well as its horrors and waste. World War I and poets like Wilfred Owen changed all that. But in 1600 the chivalric exploits of Sir Philip Sidney and the Earl of Essex still stirred men’s hearts. Shakespeare was twenty-four at the time of the Armada—still young and excitable enough to get caught up in the national fever of celebration attending the Armada’s defeat. Patriotic feelings were running high: the little island was asserting itself and beating off a huge invading force that meant to enslave it. In Elizabeth, England had a bold and charismatic leader with a great talent for rhetoric.

Ten years after the Armada’s defeat, the Globe needed a celebratory pageant for its opening season. Henry V recalls the glory days of the Armada and Elizabeth’s stirring address to her troops at Tilbury:

I know I have the body of a weak and feeble woman, but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too . . . Not doubting but by your concord in the camp and valour in the field and your obedience to myself and my general, we shall shortly have a famous victory over these enemies of my God and of my kingdom.

We can hear the echo of this in King Harry’s:

And Crispin Crispian shall ne’er go by

From this day to the ending of the world

But we in it shall be remembered,

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers.

Warfare retained something of its glamour right through the nineteenth century with its drums, bugles, resplendent uniforms and cavalry charges. The carnage of battles like Waterloo was glorified in heroic canvases. But the development of modern weaponry has put the kybosh on ‘glorious war’, apart from individual acts of heroism and self-sacrifice. Perhaps the most pathetic image of this catastrophe is to be seen in photos of the Polish cavalry in World War I (decked out in armour with angels’ wings) charging the German machine guns. In the wake of World War I, Hiroshima, Vietnam, the peace movement, Iraq, wide-scale civilian casualties and massacres, there’s precious little positive spin even the most hawkish commentator can put on war. It’s no longer a small-scale affair but involves weapons of mass destruction and fears of a nuclear holocaust.

So is it still possible to put on Henry V? It certainly is, but one needs a context. When I joined the RSC in 1965 I was given a couple of small roles (Gloucester, Governor of Harfleur, etc.) in the Barton–Hall Henry V with Ian Holm as Henry and Ian Richardson as Chorus. The compact Holm was like a plucky, shaggy Welsh pony and the French campaign recalled the Somme, with soldiers caked in mud dragging heavy wagons. The costumes had an earthy, homespun medieval reality and stood in sharp contrast to Chorus, who was a glamorous Elizabethan courier. This was a neat idea: the rhapsodic and unapologetic jingoism of Chorus was subverted by the ugly face of war itself.

When I came to direct Henry V for Bell Shakespeare in 1999 I was much perplexed as to context. The mood of the day was even more anti-war than it had been back at the RSC in 1965. The closest I could get the play to a contemporary setting was 1914. This seemed to me to be the last time the lads (whether British or Australian) sailed off voluntarily, innocent and enthusiastic, to fight on foreign soil. Prompted by the image of Kitchener and music-hall patriotic songs, they displayed a pathetic idealism and naivety. In newsreels of the day we watch them cheerily waving goodbye and we know the horrors awaiting them.

Our stage proscenium was decorated with patriotic bunting and a huge poster of Kitchener served as the backdrop. Music-hall songs were interspersed throughout the action, which was kept as grimly realistic as possible. Joel Edgerton’s Henry was a decent and candid young soldier, no chauvinist bully. I found an Australian connection by making the three discontented soldiers (Bates, Court and Williams) Aussie diggers. These are the three who have no respect for rank or title; Bates says of the King:

He may show what outward courage he will; but I believe, as cold a night as ’tis, he could wish himself in Thames up to the neck; and so I would he were, and I by him, at all adventures, so we were quit here.

Henry came across them sitting around their campfire, boiling the billy and mournfully playing ‘Waltzing Matilda’ on a mouth organ.

I’m sure many a digger on the Somme felt a similar disenchantment with ‘God, King and Country’.

I was reasonably satisfied with the production and served by an excellent cast, but I still felt frustrated that it remained a ‘period’ piece. I would have loved to have found a way to bring it right into line with here and now. The play still has enough resonance to make that possible. And the King’s great orations are masterpieces of spin. They are often played as if the second (‘St Crispin’s Day’) is merely an echo of the first (‘Once more unto the breach’), but in fact they are very different. ‘Once more unto the breach’ is full-on rhetoric and hyperbole and demands a bravura delivery. The heroics are shot through with xenophobia (‘Be copy now to men of grosser blood/And teach them how to war!’), personal provocation (‘Dishonour not your mothers; now attest that those whom you called fathers did beget you!’) and appeals to national sentiment (‘. . . And you, good Yeomen, whose limbs were made in England, show us here the mettle of your pasture’). The speech is rousing, confronting, virtually irresistible and has the desired effect on troops and audience alike. This is the speech that leads to victory at Harfleur.

When it comes time for the Crispin’s Day speech, Henry is in a very different situation. The victory at Harfleur is a distant memory. The campaign has dragged on for months and the English army is now bogged down in the middle of France, dispirited, sick, weary and depleted in numbers. Henry has spent the night before the great battle walking about the camp, listening to the apprehensions of his troops and undergoing something of a dark night of the soul. Fears about the legitimacy of his crown come flooding back as well as a general disenchantment with the very notion of kingship:

. . . O, be sick, great greatness,

And bid thy ceremony give thee cure!

Think’st thou the fiery fever will go out

With titles blown from adulation?

Earlier on he has admitted to his troops,

The King is but a man, as I am: the violet smells to him as it doth to me . . . His ceremonies laid by, in his nakedness he appears but a man.

In this one hears echoes of King Lear; for a ‘patriotic’ play, Henry V sometimes sails close to sedition. Shakespeare’s great political cunning is in putting these sentiments in the mouth not of a malcontent, but of the King himself.

Next morning he faces his troops on the field of Agincourt. They are outnumbered five to one. Time for another rousing speech . . . But this time it’s a different kind of rhetoric. Henry realises that barnstorming isn’t going to work; he looks around for inspiration. Ian Holm found a nice bit of business for this moment: one of the soldiers was kneeling in prayer, reading from his missal. Henry glanced over his shoulder and noticed that the nominated Feast Day was that of Saint Crispin and Saint Crispian, martyrs. He took the missal, looked at it thoughtfully and murmured, ‘This day is called the Feast of Crispian . . .’ The speech was improvised from there. It’s a quiet, homely speech—no grandiose words or sentiments. Henry calls all his comrades by name (including himself, ‘Harry the King’) and conjures images of rural England, of neighbours feasting, drinking, good men teaching their sons and comparing their battle scars. There’s no jot of doubt that they are going to win and return home. This quiet assurance reaches its apogee with:

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers;

For he today that sheds his blood with me

Shall be my brother; be he ne’er so vile,

This day shall gentle his condition.

No one has ever stopped to ask whether, after the battle, this promise is kept. By contrasting those two speeches one gets a very clear picture of Henry’s qualities as a leader. The art of diplomacy is largely knowing what to say and when.

So was Henry Shakespeare’s ideal king? It’s hard to say. Shakespeare seemed fascinated and repelled by him at the same time. He’s undoubtedly effective, but too reminiscent of Shakespeare’s other ‘new men’, cold-blooded pragmatists like Malcolm, Fortinbras and Octavius. His brutality is often veiled by the kind of piety we find in Richard III. But without that cold-blooded pragmatism how do you rule effectively? This is a question Shakespeare poses over and over. There is nothing inherently wrong with having power, but as Brutus notes:

The abuse of greatness is when it disjoins Remorse from power . . .

Shakespeare might have admired King Henry, but he loved Falstaff.

By the time he wrote the two parts of Henry IV, Shakespeare had fully mastered the art of characterisation. Characters such as Nym, Bardolph, Pistol, Doll, Mistress Quickly and especially Falstaff are so original, so spontaneous and individual, that they seem to write their own scripts. The machinations of the author cannot be detected. As Hazlitt puts it: ‘all the persons concerned must have been present in the Poet’s imagination, as at a kind of rehearsal, so that whatever passed through their minds passed through his.’

In Henry V the robust heroic verse is interspersed with the most natural-sounding and easy-flowing prose, as if Shakespeare had simply lifted his characters off the street outside the Globe and deposited them on the stage. Those who suggest that Henry V is simply a pageant without much plot—an invasion, a battle and a love scene—miss the point that the real plot of Henry V is the ongoing debate about war. We hear it from a conglomeration of disparate voices: the crafty churchmen, the grotty camp followers, the decent common soldiers, the boy who grows increasingly cynical and disenchanted, and the King himself, who adopts various voices and modes of speech to suit the occasion.

King John

As I mentioned earlier, I have been involved with all of Shakespeare’s history plays except two, King John and Henry VIII.

Why does no one put on King John? It really is a most interesting play with great scenes and great characters. If I put the question to myself as to why I have never put the play on, I guess it comes back to the boring old matter of box office. Would there be an audience for it? I hope I get the chance to find out one day. Admittedly, King John himself is not a charismatic drawcard; he is wily, cowardly and treacherous. And apart from defying the power of the Pope and making a stand for English Protestantism, the play is not a great historical epic. (It doesn’t even mention Magna Carta!)

The play is more concerned with personalities than historical chronicle. Constance may be the last of Shakespeare’s wailing women but she is no mere choric figure like the queens in Richard III. Her grief is humanised and affecting:

I am not mad: this hair I tear is mine;

My name is Constance, I was Geoffrey’s wife;

Young Arthur is my son, and he is lost!

I am not mad: I would to heaven I were,

For then ’tis like I should forget myself!

O, if I could, what grief should I forget!

Preach some philosophy to make me mad,

And thou shalt be canonized, Cardinal.

Falconbridge is by far the most interesting character in the play. The bastard son of Richard the Lionheart, he is the only ‘good’ bastard in Shakespeare. Lear’s Edmund and Much Ado’s Don John are embittered and malevolent social outcasts, but Falconbridge wears his bastardy as a badge of independence, of someone standing outside conventional pieties, relying on his own integrity and conscience—a good Protestant. He chooses a different path to that taken by Edmund, and is more akin to the gallant Hotspur in his disdain for self-interest, ‘commodity’:

That smooth-faced gentleman, tickling commodity;

Commodity, the bias of the world,

The world, who of itself is peised well,

Made to run even upon even ground,

Till this advantage, this vile-drawing bias,

This sway of motion, this commodity,

Makes it take head from all indifferency,

From all direction, purpose, course, intent.

And this same bias, this commodity,

This bawd, this broker, this all-changing word,

Clapped on the outward eye of fickle France,

Hath drawn him from his own determined aid,

From a resolved and honourable war,

To a most base and vile-concluded peace.

And why rail I on this commodity?

But for because he hath not wooed me yet:

Not that I have the power to clutch my hand,

When his fair angels would salute my palm,

But for my hand, as unattempted yet,

Like a poor beggar, raileth on the rich.

Well, whiles I am a beggar, I will rail

And say there is no sin but to be rich;

And being rich, my virtue then shall be

To say there is no vice but beggary.

Since kings break faith upon commodity,

Gain, be my lord, for I will worship thee!

This easygoing cynicism smacks of Edmund or even Iago, but Falconbridge is unlike the other ‘new men’ in that he has a heart. Note his compassion as he watches Hubert pick up the body of young Prince Arthur, who has leapt off the castle walls to escape his murderous uncle, King John:

Go, bear him in thine arms.

I am amazed, methinks, and lose my way

Among the thorns and dangers of this world.

How easy dost thou take all England up!

From forth this morsel of dead royalty,

The life, the right and truth of all this realm

Is fled to heaven . . .

And following King John’s ignominious death, poisoned by a monk, Falconbridge finishes the play with a stirring and patriotic call to arms:

This England never did, nor never shall,

Lie at the proud foot of a conqueror

But when it first did help to wound itself.

Now these her princes are come home again,

Come the three corners of the world in arms,

And we shall shock them! Naught shall make us rue

If England to itself do rest but true!

With its strong Protestant bias, King John provides a few problems for those who would like to see Shakespeare as a devout Catholic.

Richard II

Richard II is a more accomplished and satisfying play and, again, performed too infrequently. Maybe the poetry seems too ornate and self-conscious for contemporary tastes, but it’s very appropriate to the character of King Richard, a selfish peacock. He’s not a particularly admirable character—but how many of Shakespeare’s kings are? Those who see Shakespeare as a staunch monarchist are missing out on levels of irony and subversion.

The play was very popular throughout the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth, when public attitude to the monarchy was more romantic and nostalgic than it is today. John Gielgud’s classic performance embodied all that was sonorous, effete and decorative in the role. But since the 1960s Shakespeare has been considerably butched up.

The mid-century revolution in theatre design and directorial aesthetics that occurred in Britain was fired by the new wave of dramatists like Osborne and Wesker, the realpolitik of Polish critic Jan Kott and the leftish putsch of Oxbridge graduates who were devotees of Brecht and the Theatre of the Absurd.

In such a climate you had to look at a play like Richard II critically and ironically. But then, so did Shakespeare. He exposed Richard’s concept of Divine Right to be no more than a chimera. Richard fully expects angels to come and fight on his side but no angels front up. His faults are laid out before us; he is effeminate, treacherous (he is implicated in the death of Gloucester of Woodstock), cold and sarcastic when dealing with the dying John of Gaunt, unscrupulous in seizing the banished Bolingbroke’s property and a weak, uninspiring military leader.

But unlike King John, Richard’s faults are balanced by virtues and a humanity that eventually earn our empathy and turn him into a tragic hero. He has a great sensitivity that makes him the wrong man for the job when pitted against a pragmatist like Bolingbroke. He has intelligence, wit, a gift for poetry and rhetoric, affection for his friends and, most importantly, a growing self-awareness. He does learn something during his journey:

I wasted time, and now doth time waste me.

Richard, a delicate flower, is crushed by a brutal social environment that has no room for such an exotic. In this he reminds me of Oscar Wilde, who might serve as a role model.

While I was with the RSC I was ‘loaned out’ a few times to various regional companies, and I played Richard II at the Oldham Rep, outside Manchester. It was a very forgettable production but I was thrilled when the crates of hired costumes arrived from London. Mine was the costume Paul Scofield had worn when he played the role at Stratford. It was a great buzz for me to speak that wonderful verse and feel myself to be a part of that Gielgud/Scofield tradition.

Richard II came close to tipping Shakespeare into a catastrophe. The day before the Earl of Essex made his disastrous attempt to storm the court and wrest power from his enemies, his cronies commissioned a special performance of Richard II at the Globe on Saturday 7 February 1601. Apparently they hoped it would further their cause by demonstrating that the forced abdication of a monarch could be legitimised. The coup failed, Essex was executed and the players hauled before the authorities. Their spokesman, Augustine Phillips, was able to convince his interrogators that the actors were innocent of complicity in the plot. They had been unwilling to perform, protesting that the play was out of date and wouldn’t pull an audience; but offered a forty-shilling bonus, they had agreed to play.

The players were released, but the Earl of Southampton, Shakespeare’s patron, was condemned for high treason and thrown into the Tower. His death sentence was later commuted and, after Elizabeth’s death, the new monarch released him. It’s interesting to note that one of the interrogators in the case was Francis Bacon—one more nail in the coffin of the absurd assertion that he was the real author of Shakespeare’s plays. It’s also worth noting that Bacon despised the English language to the extent of writing or translating all his own works in Latin. He complained that ‘these modern languages will at one time play the bankrupt with books’. Not something you’d expect from the author of the greatest plays and poems in the English language! The story of the Essex rebellion and Shakespeare’s involvement in it is brilliantly recounted in Jonathan Bate’s Soul of the Age.

Henry VI

Henry VI, among Shakespeare’s earliest work, is comparatively primitive. Most of the nobles and aristocrats tend to be interchangeable. Nevertheless, looking over the vast expanse of all three Henry VI plays, we find a great gallery of characters: the saintly and mournful King himself, the magnificently feisty Queen Margaret, scheming Warwick, doughty York, brave Talbot, silky Somerset, the outrageous rebel Jack Cade and, coming up through the pack, a malevolent young hunchback named Richard, Duke of Gloucester.

To see all three plays on one day is an unforgettable theatrical experience. A great historical canvas is flung before us, its epic story crammed with plots and murders, battles and pageants, pathos and comedy. There are dozens of cameo roles that make the event an actors’ feast. It is an extraordinary feat of sustained energy, storytelling, imagination and artistic control. As someone remarked, it’s as if Shakespeare had launched his career by writing the Ring Cycle.

The big question is how a twenty-four-year-old actor and playwright came to undertake such a mighty project. He would not have ventured on it without assurance of its being produced, and it calls for a very large cast of actors with elaborate props and costumes. There are processions, coronations, battle scenes, all sorts of pomp and ceremony—making for a very lavish production, well beyond the means of most theatre companies. So someone must have commissioned it, but who? And why?

Let’s take a look at Shakespeare’s arrival in London . . . He probably left Stratford in 1587, aged twenty-three. That year had been a big year for theatre in Stratford. At least five major companies performed there in the Guild Hall, including Sussex’s Men, Leicester’s Men and the Queen’s Men. The last of these was the most prestigious and had been set up in 1583 as a propaganda tool by Sir Francis Walsingham, Secretary of the Privy Council and the Queen’s spymaster. Its leading actor was the great comedian Dick Tarlton. During the tour to Stratford a brawl broke out at the White Hound in the village of Thame. One of the Queen’s Men, John Town, killed his fellow actor William Knell. This left the company short one actor. It’s quite possible that this gave Shakespeare his break. Incidentally, Knell’s sixteen-year-old widow Rebecca, nine months after her husband’s death, married another actor from the troupe, John Heminges. Heminges was to become one of Shakespeare’s closest friends and one of the producers of the First Folio.

The Queen’s Men were given an agenda by Walsingham: they were primarily to spread Protestant and royalist propaganda throughout the country and their plays were to have English history themes. Their repertoire included The Famous Victories of Henry V, The Troublesome Reign of King John and The True Tragedy of Richard III. All the histories were labelled as ‘true’ but were in fact violently partisan. These were among the old plays that Shakespeare was later to revise and reimagine.

The Queen’s Men toured extensively, as far as Scotland and Dublin. Among the great houses they visited was Knowsley Park, the seat of the Stanley family and its head, Ferdinando, Lord Strange.

In September 1588 the Queen’s Men lost both their star player, Dick Tarlton, and their patron, Lord Dudley. A few months later Shakespeare joined a new company, Lord Strange’s Men, and stayed with them for two years. The first play he wrote for them was Titus Andronicus, an enormous success that put its young author on the map.

Ferdinando, Lord Strange, was desperately seeking some good propaganda himself. He stood eighth in line to the throne—a bit too close for comfort, as one could always be suspected of involvement in plots and sedition. He was also the head of one of England’s oldest and most staunch Catholic families and under surveillance for harbouring priests, as were other members of his family. His cousin, William Stanley, was responsible for a good deal of the regime’s distrust of the family. In 1586 he served under Leicester in the Netherlands campaign, but behind his leader’s back handed over Deventer to the Spanish. Three hundred of his troops who wished to remain loyal to the Queen were shipped out; the other six hundred crossed over, with Stanley, to Spain and the Catholics.

It was crucial for Ferdinando to make a public demonstration of his and his family’s loyalty. What better way than by commissioning the hotshot young playwright of his own private theatre troupe to write a magnificent epic spectacular depicting the Stanleys in a good light? It would be seen on the public stage by thousands of people and would serve as a stunning piece of propaganda.

Shakespeare took to his task with enthusiasm and throughout the Henry VI trilogy the Stanleys feature prominently. The three plays were written and performed by Strange’s Men in 1592 and were hugely popular. But Shakespeare saved his big finish for Richard III in 1593. Henry Tudor has arrived to liberate England from the tyrant. Shakespeare gives the Stanleys all the credit for saving the day, much exaggerating their contribution to the victory of Bosworth. In his most blatant rewriting of history, he ignores the chronicles’ record that it was Richard Bray who found the dead tyrant’s crown in a thornbush at the end of the battle. Shakespeare has Thomas Stanley himself pluck it ‘from the dead temples of this bloody wretch’ and place it on the head of Henry Tudor. What a magnificent bit of spin! According to this version it was the Stanleys who effected the end of the Plantagenets and empowered the Tudor dynasty. What more could Elizabeth ask for?

Unfortunately, the good lady seems to have been unimpressed. Suspicions against Lord Strange only increased and on 16 April 1594 he died suddenly, aged thirty-five, from a massive dose of arsenic.

Elizabeth, predictably, was distraught:

with tears . . . she professed she thought not that any man in the world loved her better than he did, that he was the most honourable, worthiest and absolutely honest man that she had in her life ever known . . .

What a performer.

The first time I saw the Henry VI plays was a television recording of the RSC’s Wars of the Roses produced in the mid-1960s by Peter Hall and John Barton. As I’ve described, for the time it was startlingly modern and topical. Costumes were still basically ‘medieval’ but not as glamorous and fussy as the previous generation of theatre design. The emphasis was on toughness and a simplicity of line. The sets were vast and brutal metallic walls. The acting was unaffected, anti-‘poetical’ and colloquial without losing its driving rhythms.

Stand-out performances included David Warner’s soulful Henry VI, Brewster Mason’s crafty Warwick and Peggy Ashcroft’s Margaret, who grew miraculously over the course of the tetralogy from skittish schoolgirl to virago military leader to a crazed, haunted crone.

Henry VI and Richard III carry on the tradition of the Queen’s Men history plays, but they are no longer mere propaganda pieces: they exhibit a great interest in character, aggression, the ethics of politics, the ambivalent nature of much human intercourse, role-playing and conscience.

Their popularity was vast. Henslowe’s account book for the Rose Theatre in April, May and June 1592 show that Henry VI: Part 1 was pulling an average audience of almost three thousand.

Its most popular scene depicted the death of Lord Talbot and his son at Bordeaux. The young Tom Nashe dashed off a ‘Defence of plays’, remarking how, despite the claims of ‘some petitioners of the Council’ that plays ‘corrupt the youth of the city’, there was a deal of patriotic fervour to be had from the theatre:

How it would have joyed brave Talbot (the terror of the French) to think that after he had lain two hundred years in his tomb, he should triumph again on the stage, and have his bones now embalmed with the tears of ten thousand spectators at least (at several times) who, in the tragedian that represents his person, imagine they behold him fresh bleeding . . .

I made my own adaptation of Henry VI for Bell Shakespeare in 2005 under the title Wars of the Roses, and, for the sake of convenience, conflated the three parts into two, which I called Henry VI and Edward IV.

At first I wanted to stage Henry VI and Edward IV on alternate nights, but as budget blowouts loomed, management became increasingly nervous about attracting audiences to the theatre on successive nights. I was persuaded, with difficulty, to further conflate the plays into one evening. I kept hacking away at the script till I got it down to three hours plus interval, still a longish evening.

The play was set in a kind of gladiatorial gymnasium with galleries of metal seats where the actors sat and watched when not involved in the action. The costuming was as contemporary as possible: different sets of camouflage fatigues with the armour a conglomerate of police riot gear and the stuff you wear for protection in gridiron, ice hockey and other ‘contact’ sports—some of it quite bizarre.

My disappointment with the severe conflation was that there was no room for characters or relationships to develop; people were no sooner on than they were off again. When all is said and done, the main thing people want from a Shakespeare production is humanity and the interplay of characters.

Richard III

Richard III remains the most popular and frequently performed of all the Histories because it is the greatest star vehicle (although Falstaff is a greater role). It also withstands the vagaries of political change: there’s no way it can be seen as a propaganda tool for the monarchy (although Olivier came surprisingly close to making it one; with a charismatic Stanley Baker as Richmond and a swelling musical score by William Walton with overtones of Elgar, he made Richard seem a mere aberration; the integrity of the crown itself remained intact).

Shakespeare’s attitude is, as always, more ambivalent than that and his play has to be seen in context of the whole cycle of history plays. Jan Kott in his seminal study Shakespeare Our Contemporary comes closest to a modern view of the Histories, seeing them as a picture of a vast political machine somewhat akin to the Wheel of Fortune. As one protagonist sinks to the bottom, another rises to the top in an inexorable cycle. This was the image I took away from the superb Georgian production starring Ramaz Chkhikvadze which I first saw at London’s Roundhouse and later at the Adelaide Festival. Richmond was a rather sinister figure: when his time came to take the crown he uttered the same manic rooster-crow that he had heard earlier from Richard.

I was lucky enough to meet Ramaz Chkhikvadze when he came to Australia. In fact he was gracious enough to come to our own version of Richard III, which was playing at the Theatre Royal in Sydney. He gripped my hand after the show and said, ‘Very plastic! Very plastic!’ I hope it was a compliment.

When I first saw Ramaz play Richard in London he had a distinctly Napoleonic look with a greatcoat, tricorn and kiss curl. (Fair enough—Napoleon was the despot who had dared invade Russia.) But when I saw the show again some years later in Adelaide, Napoleon had morphed into something resembling Stalin. When I quizzed Ramaz about this later, he gave me a wink and said, ‘Ah well, times have changed . . . Richard III is always with us.’ He also gave me an amusing illustration of how Soviet artists fooled bureaucratic spooks during the Iron Curtain era. When they mounted Richard III originally, they brought on an ailing Edward IV who was a dead ringer for Brezhnev. ‘He had medals all down the front . . . even a few down the back,’ chuckled Ramaz. The censors were checking out the dress rehearsal. ‘“Who’s that supposed to be?” they snapped. “Why, it’s Edward IV of England.” “Are you sure?” “Of course . . .”’ And the actors went on to give a very convincing pitch about Edward IV. Somehow they got away with it. ‘Richard wasn’t such a bad fellow,’ mused Ramaz. ‘He only killed fifteen people. Stalin killed twenty million.’

Unlike Henry V, Richard III is always with us. The point doesn’t need hammering home as in the Ian McKellen film version which was based on the palpably false thesis that Oswald Mosley took over Britain in the 1940s.

My earliest incarnation as Richard was based on a similar thesis, only this time it was a parody. Bertolt Brecht’s play The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui is a blank-verse reworking of Richard III set in 1930s Chicago with Richard as a grotesque morphing of Al Capone and Adolf Hitler. Richard Wherrett’s production of the play for Sydney’s Old Tote Theatre was a great success which we subsequently revived for the Nimrod Theatre. All of Hitler’s henchmen are portrayed as two-bit gangsters, idiotic and brutish. Playing a parody sometimes gets you close to the heart of the real thing: by going to the extremes of grotesque body language, emotional states and vocal gymnastics, you can release an energy and inventiveness you don’t find through text study and psychoanalysis. Playfulness can get you there quicker. Brecht loved Shakespeare’s theatre—its plain empty stage that can become anything you want; its rhetoric, its bawdiness, its violence and its political danger.

I’ve now played Richard III three times. The first was at Nimrod in a production by Richard Wherrett, designed by Kim Carpenter on a set by Larry Eastwood. We wanted something tough and menacing. Richard’s vision was of an industrial site, a kind of underground boiler or furnace room with a big oven door (overtones of Auschwitz). Larry’s set was entirely of the kind of metal plates you find in a factory environment and the clothes were based on uniforms of navvies and factory workers. I was also keen to toughen up the vocal delivery, to get away from polite middle- or upper-class delivery. So we invented a dialect which was a combination of Northern English (Yorkshire) and whatever research told us about Shakespeare’s own Warwickshire accent. In retrospect I’m not sure how well it worked but it freed us up considerably; we were still experimenting with ways not to sound ‘Shakespearean’. (We ran Richard III in repertoire with my production of Much Ado which employed Italian greengrocer accents.)

In my determination to get away from the Olivier mould—the black-haired, saturnine reptile image—I went the other way and played Richard as a fallen angel with an innocent face and mop of blond hair. My friend Peter Kenna remarked that I ‘looked like the idiot son who’s been sent out to chop the wood and comes back with the axe’. I kept the disfigurement fairly subtle except for a nasty facial birthmark and a black contact lens designed to make one eye appear smaller than the other. But one night I accidentally melted it while cleaning it.

When I directed the play for Bell Shakespeare in 1992, I played Richard again and took the production in a very different direction. Our first two productions, Hamlet and Merchant of Venice, were deliberately as contemporary as possible, so I set out to confound expectations. I wanted to explore the surreal imagery and poetry of the play, its nightmare quality (dreams and nightmares feature heavily in the text). So my designer, Sue Field, and I explored Kabuki theatre, which appealed to me for its formalism and ritualistic quality; a lot of Richard III has echoes of the medieval Mystery Plays. My central image was that of feral animals trapped at the bottom of a well shaft, scrambling over each other in their attempt to get to the top. So in the rehearsals we did quite a lot of animal improvisations from which the designer took ideas to create costumes using fur, feathers and claws. James Wardlaw based his Buckingham on a combination of panther and snake. My own references were the fox and the wolf. My favourite was Marian Dvorokovsky’s description of Lord Rivers as ‘a rooster who thinks he’s a peacock’. Where the production fell short was in that essential element of any Shakespeare production, humanity. The stylisation was all very well, but somehow the world you create on stage has to coincide at some point with a world the audience knows; the characters cannot become so stylised as to cease to be human. We have to share their dilemmas and their emotions.

I had my third crack at the role in 2002 when Michael Gow persuaded me we should do the play as a co-production between Bell and the Queensland Theatre Company. Michael’s production concept was very different to my revious two experiences. He set the play in the late eighteenth century of Hogarth on a solidly realistic set. It looked like a combination of a Georgian house interior and the Tower of London, with a winding stone staircase and French windows with iron grilles. The set had a false perspective and slightly crazy rake that made it quite quirky. It looked fairly knocked around, as did the once-splendid costumes—now stained and tattered. The impression was one of post-war devastation, appropriate to the narrative of Richard III, who emerges at the end of the Wars of the Roses. This time I based Richard on a combination of boar and hedgehog. (That’s the great thing about the role—he gets called a dog, a toad, a boar, a spider, a hedgehog—you’ve got a large menagerie from which to choose.)

I also determined to explore more scientifically the nature of his physical deformity and how that might impact on him psychologically. I sought the advice of a medical specialist who gave me a very precise analysis of Richard’s challenges—the hunchback, the shortened leg, the withered arm—and how these would have come about. I could then talk to Robert Kemp, the costume designer, about how to build those elements into the costume so that I could really feel how Richard felt. After that, the psychology is easy and Shakespeare spells out all you need to know: Richard tells you exactly how he feels about his blighted physicality and how it poisons his outlook on the world. But I still immersed myself in literature regarding psychopaths and people devoid of empathy. As well as the obvious examples like Hitler, Stalin and Pol Pot, I tried to find people with absolutely no moral compass, no concept of the suffering of others.

The relative naturalism and historical specificity of Michael Gow’s production meant I had to focus on Richard’s interplay with the other characters rather than present images of moral deformity as I had tried to in my second Richard. I felt it essential that Richard exude as much charm as possible and be plausible to the people he’s talking to. I saw Antony Sher in the role for the RSC, and though he was very nifty on his crutches, I found him such a snarling, sour and vitriolic character that I couldn’t believe for a moment that anybody would trust or support him. Unless he convinces Lady Anne of his sincere contrition and his passion for her, she looks like a fool. So do Buckingham and Clarence unless Richard persuades them of his friendship and loyalty.

The only people who see Richard’s real face are the audience; and the thrill of the performance is watching him adopt a series of masks and characteristics to suit his purpose. It’s all set up in his Act III soliloquy in Henry VI: Part 3:

Why, I can smile, and murder whiles I smile,

And cry ‘content’ to that which grieves my heart,

And wet my cheeks with artificial tears,

And frame my face to all occasions.

I’ll drown more sailors than the mermaid shall;

I’ll play the orator as well as Nestor,

Deceive more slyly than Ulysses could,

And, like a Sinon, take another Troy.

I can add colours to the chameleon,

Change shapes with Proteus for advantages,

And set the murderous Machiavel to school.

Can I do this, and cannot get a crown?

Tut, were it farther off, I’ll pluck it down.

We feel the shiver of complicity as Richard confides in us, then sets about to ensnare his victims. Chkhikvadze took this deceitfulness to delightful extremes, dropping the limp when chatting to the audience and putting it on again when talking to the other characters. His Richard was a totally political animal, embodying the lies and violence of a hated Soviet regime. In a deeply ironic performance he created a comedic monster.

Richard has often been described as a sketch for Macbeth but Richard III is theatre in its own right, and its hero a marvellous creation. He has his basis in the Vice of the medieval Morality Plays, and rejoices in his pedigree; but he is one of the first of Shakespeare’s true originals, a character with his own distinctive voice.

Towards the end of the play he suffers the nightmares and paranoia that Macbeth experiences on a more profound level, but otherwise the characters are remarkably dissimilar. Richard lusts after the crown from the very beginning. He hates and despises all mankind and is driven by the desire to be revenged on the world and humanity in general. He has not a jot of conscience in disposing of his brothers, his nephews, his wife or anyone who stands in his way. On the contrary, he delights in his machinations.

Macbeth, on the other hand, is a victim of conscience. He wants the crown but is ‘too full of the milk of human kindness’ to seize it. He has to be prompted by the witches and badgered by his wife. After he has killed Duncan he is plagued by guilt and terrible dreams. Realising there is no going back, he commissions the assassination of Banquo, which only results in a new torment, to the extent that he hallucinates. There is no character in Shakespeare with a more exquisite conscience than Macbeth.

But like Macbeth, Richard goes down fighting. Shakespeare gives both these monsters a magnificent exit, and one can’t help feeling, when they’re gone, that the world is a smaller place without them. You might not much like Macbeth, but the scale of his suffering is grand, as is his criminality.

King Henry VIII

Apart from King John, the only other Shakespeare history I haven’t been involved in is King Henry VIII, or All Is True. This play was written in 1613, two years after The Tempest, in collaboration with John Fletcher. The play is relatively disappointing given such fantastic potential for drama—the charismatic heroic prince who grows into an obese ogre; the saga of the six women unfortunate enough to become his wives; the birth of the English Reformation; the persecution of its Catholic martyrs . . . There’s enough there for two or three plays, but what we get is a stately pageant with mostly choric figures. The reason is obvious: it was far too early to write a critical appraisal of that era; the dust of the Tudor dynasty had not yet settled. So the characterisation of Henry himself is necessarily bland. The play steers clear of religious controversy. But staged with full panoply the play can still work in terms of a pageant and it does boast a couple of notable characters, namely Katharine of Aragon and Cardinal Wolsey. The latter lacks personal greatness but his downfall elicits true pathos:

. . . O Cromwell, Cromwell,

Had I but served my God with half the zeal

I served my King, he would not in mine age

Have left me naked to mine enemies . . .

Likewise, Queen Katharine in her trial scene shows courage, spirit and dignity and emerges as a true tragic heroine.

Today Henry VIII is best known for the fact that it was directly responsible for the destruction of the Globe Theatre. Sir Henry Wotton describes what happened at one of the first performances, on 29 June 1613:

I will entertain you at the present with what has happened this week at the Bank’s side. The King’s players had a new play, called All Is True, representing some Principal Pieces of the Reign of Henry VIII, which was set forth with many extraordinary circumstances of pomp and majesty.

Now, King Henry making a masque at the Cardinal Wolsey’s house, and certain chambers being shot off at his entry, some of the paper, or other stuff, wherewith one of them was stopped, did light on the thatch, where being thought at first but an idle smoke, and their eyes more attentive to the show, it kindled inwardly, and ran round like a train, consuming within less than an hour the whole house to the very grounds. This was the fatal period of that virtuous fabric, wherein yet nothing did perish but wood and straw, and a few forsaken cloaks; only one man had his breeches set on fire, that would perhaps have broiled him, if he had not by the benefit of a provident wit put it out with bottle ale.

With remarkable industry the King’s Men set about rebuilding their theatre and within a year the new Globe arose from the ashes, bigger and better than before—and this time with a tiled roof!

•

All in all, the Histories amount to an extraordinary panorama of English history. With his Henry VI trilogy the twenty-something Shakespeare had achieved the greatest dramatic epic since the ancient Greeks (excluding some of the medieval Mystery cycles). From King John through to Henry VIII we get an almost unbroken chronicle of amazing personalities and events. Shakespeare exults in the fluidity of his open stage to create a saga that constantly shifts in mood and colour—from the exquisite lyricism of Richard II to the rowdy tavern japes of Henry IV to the sinister and grotesque in Richard III. How thrilling would be the opportunity to see all ten plays in the space of a week, all performed by the same company. What a reflection on humanity, kingship, power, politics, ambition, villainy, cruelty, honour, courage and the vagaries of fortune.

There is a curious little scene towards the beginning of Henry V at the siege of Harfleur. During a lull in the fighting an argument develops between four captains—an Englishman, a Scot, a Welshman and an Irishman. They are about to come to blows when the trumpet sounds, calling a parley, and they all exit together. Henry V is bringing together all the disparate elements in his territories to fight in a common cause, just as James I was doing his utmost to forge England and Scotland into a United Kingdom. What Shakespeare is dramatising is the creation of a nation, and in so doing he is largely responsible for creating that nation’s soul.

Shakespeare is above all writers, at least above all modern writers, the poet of nature . . . Shakespeare’s plays are not in the rigorous and critical sense either tragedies or comedies, but compositions of a distinct kind; exhibiting the real state of sublunary nature, which partakes of good and evil, joy and sorrow, mingled with endless variety of proportion and innumerable modes of combination; and expressing the course of the world, in which the loss of one is the gain of another; in which, at the same time, the reveller is hasting to his wine, and the mourner burying his friend; in which the malignity of one is sometimes defeated by the frolic of another; and many mischiefs and many benefits are done and hindered without design.

Dr Samuel Johnson, Preface to Shakespeare

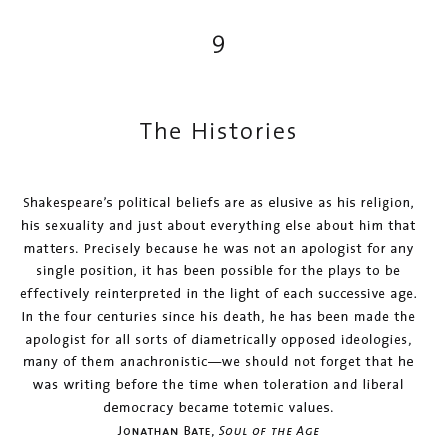

Daniel Lapaine and Essie Davis as Romeo and Juliet (1993)

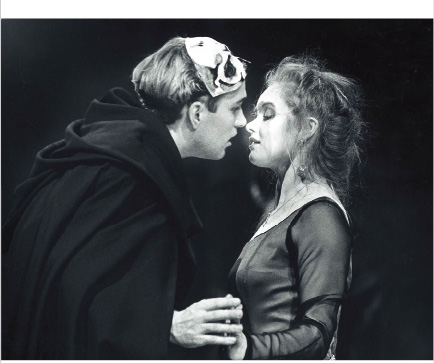

Luciano Martucci as Hector, Troilus + Cressida (2000)

Michael Craig as Caesar and Christopher Stollery as Mark Antony, Julius Caesar (2001) (PHOTO HE IDRUN LÖHR)

Paula Arundell as Cleopatra, Antony and Cleopatra (2001) (PHOTO HE IDRUN LÖHR)

Amy Mathews, Matt Edgerton, Ed Wightman and Briony Williams on the road (2002) (PHOTO BELL SHAKESPEARE )

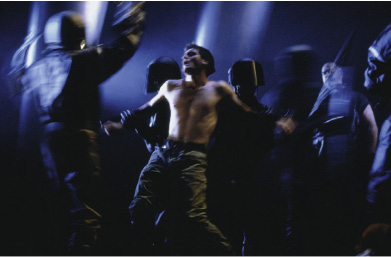

Blazey Best as Lady Anne and myself as Richard, Richard III (2002) (PHOTO HE IDR UN LÖHR)

Leon Ford as Hamlet with Bille Brown as the Gravedigger, Hamlet (2003) (PHOTO HE IDRUN LÖHR)

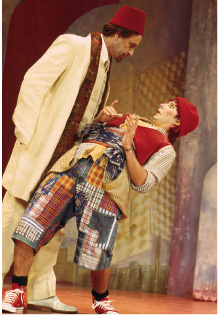

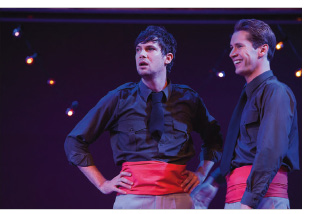

Christopher Stollery as Antipholus of Syracuse with Paul Eastway as Dromio of Ephesus, Comedy of Errors (2004) (PHOTO HE IDRUN LÖHR)

Blazey Best as Adriana and Jody Kennedy as Luciana, Comedy of Errors (2004) (PHOTO HE IDRUN LÖHR)

Death of Talbot—Wars of the Roses—Georgia Adamson as Joan, Peter Lamb as Talbot (2005) (PHOTO HE IDRUN LÖHR)

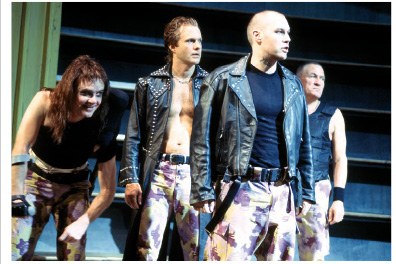

The Yorkist Brat-pack, Wars of the Roses. Darren Gilshenan, Julian Garner, David Davies, Richard Piper (2005) (PHOTO HE IDRUN LÖHR)

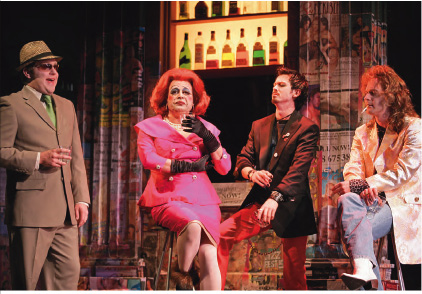

David Hynes (Gentleman), Garry Scale (Mistress Overdone), Matthew Moore (Lucio) and Julian Garner (Froth), Measure for Measure (2005) (PHOTO WENDY MCDOUGALL )

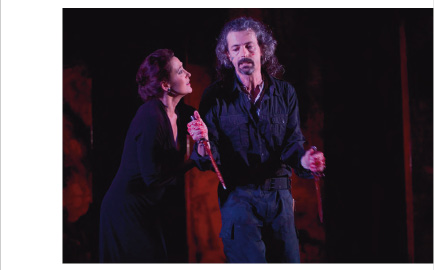

Linda Cropper as Lady Macbeth and Sean O’Shea, Macbeth (2007) (PHOTO WENDY MCDOUGALL )

Leeanna Walsman as Desdemona, Wayne Blair as Othello (2007) (PHOTO WENDY MCDOUGALL )

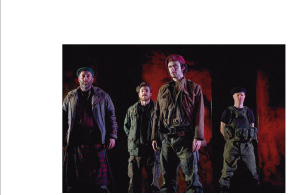

David Whitney (Macduff), HuwMcKinnon (Lennox), Tim Walter (Malcolm), Richard Sydenham (Angus), Macbeth (2007) (PHOTO WENDY MCDOUGALL )

Wayne Blair as Othello (2007) (PHOTO WENDY MCDOUGALL )

Lizzie Schebesta as Ursula, Megan O’Connell as Margaret, Alexandra Fisher as Hero, Tony Llewellyn-Jones as Leonato, Arky Michael as Antonio, Robert Alexander as Friar Francis, Tyran Parke as Balthasar and Blazey Best as Beatrice, Much Ado About Nothing (2011) (PHOTO WENDY MCDOUGALL )

Toby Schmitz as Benedick, Blazey Best as Beatrice and Matthew Walker as Don Pedro, Much Ado About Nothing (2011) (PHOTO WENDY MCDOUGALL )

Toby Schmitz as Benedick and Matthew Walker as Don Pedro, Much Ado About Nothing (2011) (PHOTO WENDY MCDOUGALL )

Saskia Smith (Rosalind), Damien Ryan (Jaques) in As You Like It (2008) (PHOTO WENDY MCDOUGALL )

Pippa Grandison, Patrick Brammall, Tim Richards playing at witches in Andy Griffith’s Just Macbeth! (PHOTO WENDY MCDOUGALL )

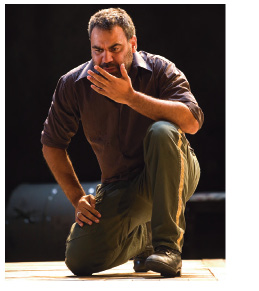

Robert Alexander and myself in Titus (2008) (PHOTO CRA IG RATCL IFFE )

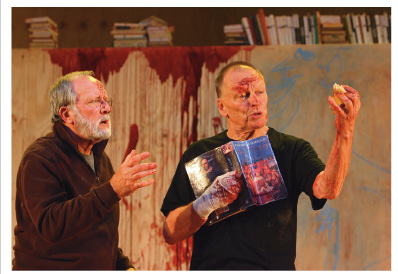

Bloody but unbowed . . . the cast and crew of Titus after a performance (2008) (PHOTO BELL SHAKESPEARE )

Susan Prior and Melissa Madden Gray in Marion Potts’ version of Venus + Adonis (2008) (PHOTO JEFF BUSBY )

Andrea Demetriades as Marina in Pericles (2009) (PHOTO WENDY MCDOUGALL )

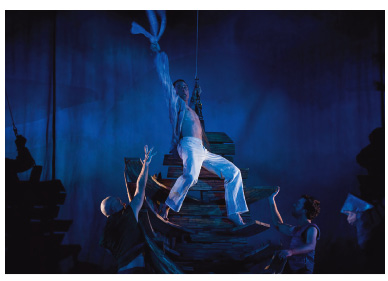

Marcus Graham as Pericles (2009) (PHOTO WENDY MCDOUGAL )

Myself as Lear with Peter Carroll as The Fool, King Lear (2010) (PHOTO WENDY MCDOUGAL )