CHAPTER I

“Please Accept My Resignation”

Chicago’s excavations at Megiddo almost ended less than a week after they officially began. Just four days into the first excavation season, in early April 1926, Clarence S. Fisher, the newly appointed field director, sent a cable back to Chicago. In it, he stated bluntly: “HIGGINS’ ATTITUDE MAKES FURTHER ASSOCIATION IMPOSSIBLE STOP DUAL DIRECTION ALWAYS DESTRUCTIVE OF BEST RESULTS STOP PLEASE ACCEPT MY RESIGNATION.”1

It is perhaps fitting for a site that has seen so many major battles fought in its vicinity during the past four thousand years to also be the scene of a struggle for control of the excavations meant to unearth its secrets. However, Megiddo is not the first archaeological site at which such power struggles have taken place, nor will it be the last.

Breasted cabled back almost immediately, refusing to accept Fisher’s resignation and assuring him that there was only one director: “DEEPLY REGRET TROUBLE,” he wrote. “PLEASE UNDERSTAND YOU ARE SOLE DIRECTOR AT MEGIDDO STOP THERE IS NO DUAL DIRECTION AM CABLING HIGGINS STATING WORK IS UNDER YOUR SOLE INSTRUCTIONS.”2

The tension had begun months earlier, when Clarence Fisher and Daniel Higgins both arrived at Megiddo in September 1925. However, the full story actually begins nearly a hundred years before that, in mid-April 1838, when Edward Robinson, an American minister, stood with his missionary colleague Eli Smith on top of a tall mound known in Arabic as Tell el-Mutesellim—“the Hill of the Governor.”

Robinson and Smith were in the Jezreel Valley of what is now the modern state of Israel, intent on locating biblical sites in the Holy Land. Already they had pinpointed dozens to their satisfaction, based on similarities between modern village names and ancient places.

MAP 1. Detail from the Survey of Western Palestine (Sheet VIII) by Conder and Kitchener (PEF-M-WS-54.2; courtesy of the Palestine Exploration Fund)

Robinson, who was a professor at Union Theological Seminary, was certain that Megiddo lay somewhere in the vicinity of Tell el-Mutesellim. However, he didn’t realize that he was actually standing on top of Megiddo at that very moment. In fact, he dismissed the mound as a possibility, stating, “The Tell would indeed present a splendid site for a city; but there is no trace, of any kind, to show that a city ever stood there.”3 Ultimately, Robinson decided that the nearby village of Lejjun covered both ancient Megiddo and Roman Legio.

Thirty-five years after Robinson and Smith, Lieutenants Claude R. Conder and Horatio H. Kitchener, who were surveying the western Galilee on behalf of the Palestine Exploration Fund (PEF), also stood on top of Tell el-Mutesellim. This time, though, they did notice traces of ancient remains. The upper parts of the mound were covered with thorns or cultivated, but under the vegetation lay “a city long since completely ruined.” Everywhere they looked, there were foundations of buildings and broken pieces of pottery.4

Nevertheless, like Robinson and Smith, they still didn’t identify Tell el-Mutesellim as Megiddo.5 Their reluctance was based in part on the fact that, three years earlier, Conder had suggested that Megiddo might be located farther down the valley, at “the large ruined site of Mujedd’a at the foot of Gilboa,—a mound from which fine springs burst out.”6

The debate over the location of biblical Megiddo continued for another two decades, until the Scottish theologian George Adam Smith convincingly showed that Megiddo and Tell el-Mutesellim were one and the same. He did so by using both direct and indirect evidence, including connecting biblical passages to geographical locations and documenting mentions within Egyptian inscriptions in his 1894 book The Historical Geography of the Holy Land, which was a landmark publication in all senses of the word.7

Breasted had been wanting to begin digging at Megiddo ever since June 1920, for the site had lain untouched following the conclusion of Schumacher’s excavations fifteen years earlier. It was Lord Edmund Allenby, hero of the Allied forces in the Middle East during World War I and victor of the battle fought at Megiddo in 1918, who convinced Breasted that he should begin a new series of excavations at the ancient site. “Allenby of Armageddon,” as he was frequently called, though his official title was “Viscount Allenby of Megiddo,” had won the 1918 battle at the ancient site in part because of Breasted’s multivolume publication, Ancient Records of Egypt, which appeared in 1906. In one of those volumes, Breasted translated into English the account of Pharaoh Thutmose III’s battle at Megiddo. Breasted’s translation allowed Allenby to successfully employ the same tactics thirty-four hundred years later.8

However, June 1920 was a tense time. There had been riots in Jerusalem a few months earlier, back in February and March, when the British announced their intention to implement the Balfour Declaration of November 1917 and create a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine. More riots, with nine people killed and nearly 250 injured, took place just a month before Breasted’s attempted visit to Megiddo, when Easter Sunday and the Muslim celebration of Nebi Musa coincided.9

As it was, Breasted had to content himself with seeing Megiddo from a distance that June. In part, this was because it wasn’t considered safe to cross the last few miles owing to bandits, but it was also because of a frustrating series of car problems and dysfunctional directions. “After having driven for hours along the hills on the north side of the plain of Megiddo, until we were far up toward Nazareth,” Breasted wrote the next day, “we found that neither of our drivers knew the road.… For over two hours we drove over plowed fields and dry stubble land … staring helplessly at the walls of distant Megiddo which challenged us from across the plain.”10

Although he had failed to make it to Megiddo, from Nazareth Breasted could see a mixture of sights and sites—geographical, historical, and religious. From here, the Jezreel Valley appeared like a triangle lying on its side. Its tip was out of view, off to the west by Haifa and the Mediterranean Sea, while its broad base lay approximately twenty-four miles (38 km) to the east, at the Jordan River.

The valley itself is quite narrow where Breasted stood, just eleven miles (18 km) across as the crow flies, which is why Napoleon reportedly once called it “the most perfect battleground on the face of the earth.”11 Perhaps fittingly, somewhere between Megiddo and Nazareth, in the heart of the valley, the “secret” Israeli air force base of Ramat David is now located. It is not shown on any maps of the region but, ironically, has its own Wikipedia page. It’s certainly not a secret to any of the inhabitants in the valley, or the modern excavators at the ancient site, who are treated to daily sights of F-16 jets taking off and then landing again at ear-shattering volume.

To the west, just shy of the Mediterranean, Breasted could see Mount Carmel in the distance. Here, the Hebrew Bible says, Elijah once had a contest with the prophets of Baal (1 Kings 18:16–46); a Carmelite monastery now marks the reported spot.

To the east, he could see Mount Tabor. According to the biblical account, the Israelite troops of Deborah and Barak charged down its slopes, fighting against the forces of the Canaanite general Sisera, probably in the twelfth century BCE (Judges 4:1–24). The Transfiguration of Christ reportedly took place here more than a thousand years later; three separate churches now mark the spot at the summit of the mountain—the largest one was commissioned by Benito Mussolini.

Even farther east, and almost out of sight for Breasted, lay Mount Gilboa. Here, the Bible tells us, King Saul and three of his sons met their deaths at the hands of the Philistines in the eleventh century BCE (1 Samuel 31:1–12; 1 Chronicles 10:1–12). Nearby is the site of ancient Jezreel, where Jezebel was reportedly thrown out of a window and then trampled to death (2 Kings 9:10, 30–37).

MAP 2. Megiddo and surrounding area, drawn by Edward DeLoach; published in Guy 1931: fig. 2 (courtesy of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago)

Much closer, also to the east and not more than a thousand yards away from the site of Megiddo, Breasted spied the junction where the Musmus Pass—also known as the Wadi Ara and the Nahal Iron—comes into the valley. It was through this pass that the armies of both the Egyptian pharaoh Thutmose III and the Allied commander General Edmund Allenby successfully marched in 1479 BCE and 1918 CE, respectively, en route to capturing Megiddo. In recording his victory on the walls of a temple in Luxor down in Egypt, Thutmose said that the capturing of Megiddo was “like the capturing of a thousand cities.”12

Thutmose was not exaggerating, for Megiddo controlled the entrance to the Jezreel Valley from the west throughout antiquity. The Via Maris (literally the “Way of the Sea,” as the later Romans called it) ran through the valley, serving as a main road for travelers and armies alike moving between Egypt in the south and Anatolia (modern Turkey) or Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) in the north. As both Breasted and Thutmose III well knew, if you controlled Megiddo, the rest of the region followed. Virtually every invader of the area fought a battle here in antiquity.

For Breasted, as it is for visitors today, the view across the length and breadth of the Jezreel Valley was breathtaking and the sense of history overwhelming. With just a bit of imagination, he could visualize the armies of Napoleon, the Mongols, Mamlukes, Egyptians, Canaanites, crusaders, Israelites, and others marching across the valley floor. All have fought here: biblical Deborah, Gideon, Saul, and Jonathan; Pharaohs Thutmose III and Sheshonq; Generals Kleber, Baibars, and Allenby; and unnamed soldiers in the hundreds and thousands. Many have died here. It is a sobering reminder of our place in the grand scheme of things.

At the time that he was trying to visit Megiddo, Breasted had just founded the Oriental Institute (OI) at the University of Chicago, courtesy of a large grant from John D. Rockefeller, Jr. He was now on the hunt for promising sites that the new institute might excavate, making “a daring reconnaissance trip through the Near East to survey the possibilities for research work … [c]rossing territory which was still virtually in a state of war.”13

Breasted contacted John Garstang, who was the director of the brand-new British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem. More importantly, Garstang had also just been named director of the newly established Department of Antiquities in British Mandate Palestine. Breasted requested that a formal application be made on his behalf to the Archaeological Advisory Board, such that “the site of Megiddo be reserved for the period of one year to the University of Chicago with a view to excavation under the terms of the Law.” By late November, he had been promised an excavation permit, valid for one year.14

Breasted’s actions were part of a larger movement by American archaeologists at that time. Archaeology in the region was still in its infancy in those days, and archaeological expeditions up to that point had been rather haphazard. Even the headquarters of all the foreign schools of archaeology in Jerusalem were still relatively new, with the German Protestant Institute of Archaeology, the École biblique et archéologique française, and the British School of Archaeology, as well as the American School of Oriental Research, having been recently founded. In fact, even the field of archaeology as a discipline was still young at that time. Heinrich Schliemann’s excavations at Troy, in which he was actively searching for proof of the Trojan War, had begun only fifty years earlier, in 1870, and Howard Carter was still two years away from finding the tomb of Tutankhamen, in 1922.15

The British archaeologist Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie and the American Frederick Jones Bliss, digging at the site of Tell el-Hesi one after the other (1890 for Petrie, 1891–92 for Bliss), had been at the forefront of the field.16 They were the first to realize that “tells” were man-made, consisting of multiple cities built one on top of another. They also borrowed from geology by introducing the concept of stratigraphy, which held that the lowest levels in the tells were usually earlier than the ones nearer the top. And they realized that because pottery types go in and out of style over time, they could be used to help date the various stratigraphic levels within a mound, as well as to indicate which levels at different sites were contemporary with each other.17

Their techniques were adapted and improved upon by other archaeologists. With some exceptions (notably the Irish archaeologist R.A.S. Macalister, who tended to ignore both stratigraphy and the precise location of the small finds that he came across while digging at the biblical site of Gezer during the periods 1902–5 and 1907–9), each archaeologist continued to improve upon the methods of the others.

Having been promised an excavation permit, Breasted approached Harry Judson, president of the University of Chicago, to discuss how he might finance the proposed excavation. Judson told him to put his thoughts into a letter that could be used in a pitch made to Rockefeller and other possible donors. Breasted promptly did so, ending his letter with a succinct financial assessment: “To make a complete clearance of the ancient city, its walls, its stronghold, citadel, palace, and houses, and to publish the results, would require a budget of Sixty Thousand Dollars ($60,000.00) each year for four years.”18

Judson, in turn, immediately contacted Rockefeller, to ask whether he would be willing to fund this additional project. It would be a worthwhile endeavor, he suggested, for the results “may … cast a flood of light on the past of civilizations.”19

Rockefeller was intrigued. Moreover, he liked Breasted. “I enjoyed knowing him and seeing him,” Rockefeller once said. “He was a charming gentleman and a distinguished scholar, with the modesty of the truly great. My interest in archaeology was wholly the result of his influence.”20 However, since Rockefeller was not prepared to underwrite all four years of exploration, he offered to give $60,000 for the first year of excavation, on the condition that money for the additional three years came from elsewhere.21 In early July 1921, the New York Times briefly announced the plan to excavate Megiddo, with the headline “To Excavate Armageddon; John D. Rockefeller Jr. Gives $60,000 to Dig Up the Site.”22 Unfortunately, Breasted was unable to raise the additional funds at the time, but he retained the option to dig at the site at some point in the future.

Three years later, in August 1924, probably stimulated by a letter that Clarence Fisher had sent to him a few weeks earlier, Breasted wrote to Rockefeller, asking whether the initial pledge was still on the table. He reiterated his interest in excavating “this remarkable stronghold of Armageddon,” as he called it, noting that it “has become the proverbial symbol of the struggles of man, where Asia and Africa fought for supremacy for thousands of years.” By mid-November, Rockefeller agreed to extend his pledge of $60,000 until July 1925, on the continuing condition that Breasted was able to procure the additional money needed from elsewhere.23

At this point, although it may seem that we are getting too far down in the weeds, it is necessary to continue our deep dive into the events leading up to the first season of excavation at Megiddo. The excursus will be worthwhile, for it is here that we meet the initial team members, some of whom will play a role at the site for years to come, as well as some of the other archaeologists with whom they would interact.

We therefore pick up the action again with the letter that Fisher sent to Breasted in mid-July 1924. In it, he asked whether Breasted planned to begin digging at Megiddo soon, and, if so, whether he could assist in any way.24 Fisher was familiar with the site, having visited it in 1921 as part of a tour of the area arranged by William Foxwell Albright and the American School of Oriental Research in Jerusalem.25

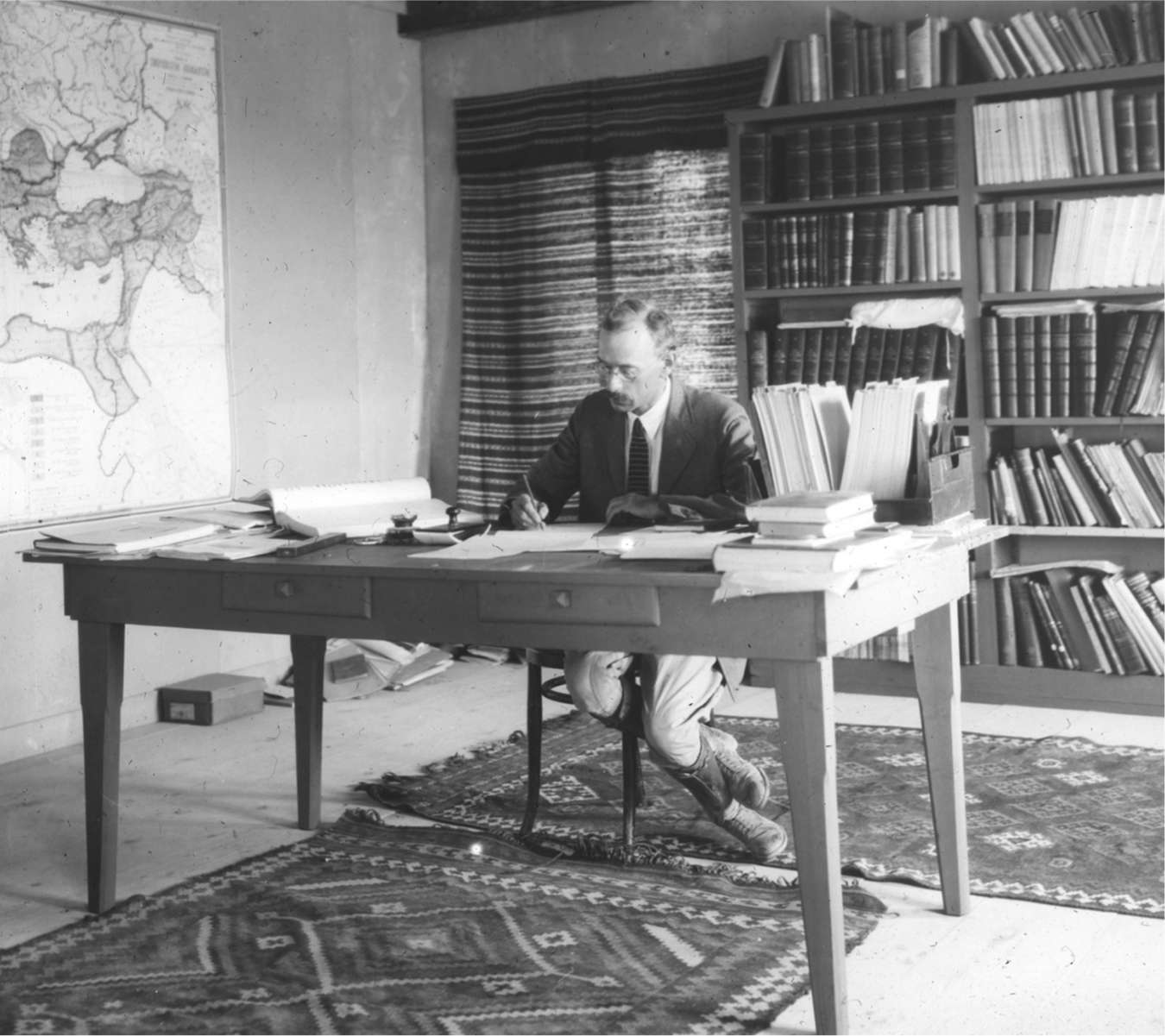

Although originally trained as an architect at the University of Pennsylvania, from which he had graduated in 1897, Fisher identified himself as an archaeologist on all his passport applications and other official documents. A slim bookish man of about five feet eight, who also favored wire-rim glasses and sported a mustache, Fisher had quite a bit of experience by that point. He had excavated at Nippur in Mesopotamia in 1900 and with George Reisner of Harvard University at Samaria in Ottoman Palestine in 1909–10. He had also directed excavations in Egypt for several seasons. At the time that he wrote to Breasted, he was back at the University of Pennsylvania, employed at the University Museum as a curator, and had been directing their excavations at Beth Shean (Beisan) in British Mandate Palestine for three seasons, from 1921 to 1923.26

FIG. 4. Clarence Fisher at work (courtesy of the Oberlin College archives)

Fisher was among the best practitioners of his time, having adapted and improved upon Reisner’s methods, mainly by opening up large horizontal areas all at once while digging at Beth Shean, in order to see as much as possible of a single level before proceeding down into the next one. He would later teach many others over the years, including Albright in the early 1920s.

At the time, Albright was just getting his own start in the field of biblical studies and archaeology, having received his PhD from John Hopkins University in 1916. He would later go on to become one of the most influential people in the field of biblical archaeology, as well as related disciplines, including serving as director of the American School of Oriental Research in Jerusalem, which is now named after him. He would also become Breasted’s greatest rival in certain ways, and though there was mutual respect, there was no love lost between the two men.27

Fisher did not mention to Breasted what had prompted his inquiry in mid-July 1924, but he was not happy about the salary that he was receiving at the University Museum at the time, nor with his unsuccessful attempts to get permission from George B. Gordon, director of the museum, to hire an assistant.28 He also probably foresaw that his time at the University of Pennsylvania was about to end, for he had been removed from the directorship of the Beth Shean excavations several months earlier. In fact, Fisher took matters into his own hands and fired off a letter of resignation in early December, although it took nearly a month for it to reach Dr. Charles C. Harrison, president of the museum’s Board of Managers.29

Meanwhile, having heard from Rockefeller that his pledge would be extended, Breasted reached out to Fisher later that same month.30 At the same time, he contacted Garstang again, asking that the permit for the excavation of Megiddo be extended until the end of 1925, which would give him enough time to raise the necessary funds.31

In early January, Garstang and the Archaeological Advisory Board agreed to extend the permit for Megiddo.32 The official letter was sent on the exact same day that Philadelphia-area newspapers announced that Fisher and the University Museum had parted ways.33

The museum’s official explanation was that Fisher had been let go because of ill health and his poor physical condition, but Fisher afterward insisted that he had resigned rather than been fired, because he had not been allowed to select his own assistant. In fact, he provided his letter of resignation to the Philadelphia newspapers, declaring, “If I leave the University Museum, I shall most certainly associate myself with the expedition of some other institution and continue my researches in the East.” He subsequently did exactly that, at Megiddo.34

Eventually Gordon provided more of the backstory to Alan Rowe, who had taken over from Fisher as director at the Beth Shean excavations. According to Gordon, Fisher had been let go at Beth Shean because his “mental and physical health made it impossible for him to represent the Museum or to conduct the work of our Expeditions in the field.” Fisher was ordered to return to Philadelphia, but there “his symptoms grew more aggravated [and] he … appeared to labour under the false idea that he was persecuted.”35 In the end, when Fisher offered his resignation from the museum, both Gordon and Harrison were undoubtedly relieved.

Fisher remained in contact with Breasted, writing again in February to indicate his continued interest—which was not surprising, since by that time he was out of a job.36 Meanwhile, Gordon was sure that Breasted had no idea of the events that had transpired both at Beth Shean and in Philadelphia, writing to Rowe, “I understand that Professor Breasted is in charge of the University of Chicago Expedition at Megiddo. I should add to what I have said that Professor Breasted knows nothing at all about Mr. Fisher’s conduct while connected with this Museum nor the circumstances under which he left its employ.”37 However, Breasted was probably quite aware of what had happened, for he was extremely well connected and often had news of events long before others did.38

Breasted next wrote to Raymond Fosdick, who was close to Rockefeller. At the time, Fosdick was a member of the board for all three Rockefeller philanthropic organizations that subsequently would be involved with the Megiddo excavations: the Rockefeller Foundation (RF), the General Education Board (GEB), and the International Education Board (IEB); he later became president of the first two boards.39

In his letter, Breasted reiterated much of what he had written in his original sales pitch back in March 1921, particularly about the importance of Megiddo/Armageddon.40 He also told Fosdick that he had been unable to raise the additional funds beyond Mr. Rockefeller’s pledge to fund one season of work at Megiddo because of an endowment campaign being run concurrently by the University of Chicago. Therefore, but also because expenses in the Near East had fallen slightly in the interim, Breasted now proposed an “entirely new Megiddo Project” for which he needed $15,000 for equipment (including tents, furniture, and Decauville railway cars and tracks for hauling away the dirt) plus funds for five years of work at $40,000 per year, for a total of $215,000.41

As an impetus to get Fosdick to persuade Rockefeller to pledge the entire amount, Breasted wrote that another factor relevant to the revised project was that “an admirable man is in sight to take charge of the Megiddo excavations.” We might be forgiven for thinking that Breasted then extolled at length the virtues of Fisher, with his previous dig experiences in Egypt and at Samaria and Beth Shean, but that was not the case. Instead, Breasted wrote, “This man, whose name is Higgins, is firstly a trained geologist with wide field experience in many parts of the world. He has, for example, made a survey of the Peninsula of Sinai and knows all about its resources in oil and minerals. He can accept at any moment tempting commercial offers. But his heart is in archaeological field work. Such a man is a far better field director than the academic scientist. I am very anxious to save Higgins for such work.”42

What had happened? It seems that—possibly because of the events relating to Fisher and the University of Pennsylvania Museum—Breasted had initially decided not to offer Fisher the directorship of the dig, but instead to put this geologist, Daniel F. Higgins, Jr., in charge. It is unclear why Higgins’s heart lay “in archaeological field work,” as Breasted put it, because he had no specific archaeological experience whatsoever. Nevertheless, in all other respects, Higgins’s credentials certainly seemed impeccable—he had been trained at the University of Illinois, Northwestern University, and the University of Wisconsin, and was currently teaching geology at the University of Chicago. He had worked in Korea and China, and then for the US Geological Survey, fought in World War I with the British Expeditionary Force, and conducted explorations and surveys in both the Sinai and Egypt. He had also been married for fifteen years by that point; as newlyweds, he and his wife, Ethel, had served as Methodist missionaries and taught in Korea for two years, from 1910 to 1912. They had two young daughters: Mary, who had been born while they were in Korea and was now fourteen years old, and Eleanor, who was born while they were in China and was now nine years old. As might be expected, they were all quite willing to move to the Middle East.43

However, Fosdick very nearly torpedoed the entire proposal. Although he dutifully forwarded it to Rockefeller, he began by noting, “At first sight this new proposition seems to propose an arrangement of doubtful wisdom, inasmuch as it puts the entire burden [of funding the work] upon you.” Nevertheless, he also pointed out that “in Dr. Breasted we have a uniquely trained man … certainly there is no one better in the world at the present time. The question is whether we ought to avail ourselves of the services of Dr. Breasted while he is still living and in his prime.”44

Rockefeller felt that the answer was yes. After an additional conversation with Fosdick, Rockefeller authorized him to go all in and pledge the entire amount of $215,000 that Breasted had requested, which is the equivalent of nearly $3,000,000 today.45

The welcome news reached Breasted just hours before he departed for England on the SS Homeric. This was a splendid and luxurious passenger ship that began life as the German superliner Columbus in 1913. It was acquired by Great Britain in 1919 as part of the Treaty of Versailles, sold in 1920, and then finally completed and put into service by the White Star Line in 1922.46

As the ship pulled away from the North American coastline, Breasted cabled Daniel D. Luckenbill, whom Breasted affectionately addressed as “D.D.” in all of his communications. Luckenbill was a distinguished professor of Assyriology and one of Breasted’s closest colleagues at the Oriental Institute, with whom he had been discussing the various possibilities concerning Megiddo.47 Swearing him to secrecy, Breasted followed up a few days later with a letter, also sent from on board the ship.

He asked Luckenbill whether, rather than Higgins, Fisher were still available. However, he also asked whether Luckenbill had any other suggestions for a field director, since Breasted wasn’t completely sold on Fisher in that capacity.

It is not entirely clear why Breasted had decided not to ask Higgins to head the project after all, as he had proposed to Fosdick back in May. His decision may be related to the fact that Breasted was initially unsure about hiring Higgins at all but had been persuaded by Luckenbill, who swore that Higgins was the best photographer he had ever met, in addition to being a geologist and a surveyor.48 More likely, it had to do with the fact that Breasted had realized Higgins needed additional archaeological training before he could be put in charge of the entire operation. Therefore, he decided that Higgins would be second in command, under Fisher’s direction, and Fisher would train Higgins in how to run an excavation.

Although he had concluded that there was no one else available on such short notice, Breasted confided to Luckenbill, “poor Fisher is almost neurotic. It is very likely that after having started our expedition and gotten it into good running order for a few months, he will go off the deep end as he has done now with several successive groups of men.” He continued: “I don’t mean that I am taking Fisher with the deliberate intention of splitting with him. He is a very valuable man, and if his health will permit him to go on with us, I am and would be strongly in favor of keeping him; but there is every likelihood that things will go as I have suggested above.”49

As it turned out, Breasted was prescient, for that was exactly what happened. But all of that lay in the future, and so, with no other suggestions forthcoming, Breasted cabled Fisher as soon as he reached London. “CAN YOU ACCEPT FIELD DIRECTORSHIP MEGIDDO EXCAVATIONS?” he asked.

Fisher accepted the offer almost immediately, but only after Luckenbill went to Philadelphia to talk it over with him in person. “FISHER ACCEPTS,” Luckenbill cabled Breasted tersely. He then followed up with a longer cable and an even longer letter, for Fisher had suggested that they should begin immediately, by surveying the mound from September through March and then excavating from April through October. Both Breasted and Luckenbill liked the plan.50

Luckenbill and Fisher also discussed the arrangement to have Fisher train Higgins, which Fisher found appealing. Luckenbill reported that Fisher would take Higgins “in hand at once and train [him] for the work. He seems to think that one season would do that job. So do I. Thereafter, we would still have Fisher’s advice and help, but things would fall to Higgins and assistants.”51

Breasted was pleased to hear that Fisher had accepted the position. He filled Fisher in on the financial details, noting that they had enough money for a five-year campaign: $55,000 for the first season, which included $15,000 for equipment and the construction of a dig house at the site and $40,000 for the actual season, plus $40,000 for each season thereafter. Since that came to $215,000—exactly the amount that Breasted had requested in his modified plan and which Rockefeller had just donated—Fisher’s salary of $5,000 per year plus traveling expenses would come from somewhere else in Breasted’s annual budget for the Oriental Institute.52

At the same time, Breasted contacted Garstang once again, this time requesting that the official excavation permit finally be issued. He told Garstang that they had succeeded in procuring the funds and that Fisher would be directing the field operations.53

Overall, as Breasted saw it, they needed four people on staff: (1) a manager/administrator; (2) an archaeologist; (3) an epigrapher/philologist (to read the inscriptions he was expecting that they would find); and (4) a surveyor/draughtsman/plan-maker. He also suggested that they should take on a student to assist with the work.54 Of course, on an excavation conducted today, we would have many more staff members; it is unfathomable to have only a single archaeologist present at a site during the digging season now, but that was common practice in those days.

As for the student whom he had envisioned taking part in the project, Breasted settled on a young man named Edward DeLoach as an assistant for Higgins, whom both Higgins and Luckenbill had recommended. DeLoach was twenty-four years old, the son of a good friend of Luckenbill’s. He was originally from Georgia but as a student at the University of Chicago had taken surveying classes taught by Higgins. Fisher approved of this plan as well, since he had suggested to Luckenbill that they should take with them “a youngster or two and interest them in archaeology.” At the time, DeLoach was working as a surveyor down in Post, Texas, but he responded promptly and positively to the invitation to participate at Megiddo that Higgins sent to him in July 1925. His only question, as he told his mother, was how much they were going to pay him.55

Breasted was pleased with all of this and told Fisher that he was confident Higgins would be “a very useful and good man,” for Higgins not only understood how to make maps and plans but was also accustomed to managing men.56 In fact, Fisher found Higgins to be neither useful nor good; nor did any of the other Megiddo team members have a more positive reaction. This was eventually made clear by separate correspondence between Breasted and others, including a former Yale student named John Payne Kellogg, who—unbeknownst to the others—became Breasted’s informant from mid-May 1926 onward, surreptitiously reporting directly to him on everything from their emotions to the discoveries made by the team.

Breasted later told Garstang that Higgins had come highly recommended by the Department of Geology at the University of Chicago. However, as he concluded, “Regarding our complete disappointment in this direction I need not say more. The fact that our one year contract with Higgins has not been renewed is probably sufficient comment.”57

By early July 1925, before all the trouble with Higgins came to pass, and exactly one year after he had first written to Breasted, Fisher began making plans to have equipment purchased and shipped to Megiddo. Higgins did the same, beginning in early August. This included equipment for surveying and photography, as well as for the light railway that would be used to haul away the excavated dirt. Fisher requested a car, specifically a Dodge or a Buick sedan, and proposed that a young Egyptian, with whom he had worked in Egypt, serve as overseer of the workmen. He also suggested that Higgins might sail over on the same steamer, so that they “could then get acquainted and talk over plans,” though that didn’t materialize.58

In the meantime, Garstang sent Breasted the official permit to dig at Megiddo, confirming that the work would be conducted under the field directorship of Fisher. Fisher himself made arrangements to sail by mid-August, so that he could begin work at Megiddo in early September.59 This would allow the team to do a preliminary survey of Megiddo, begin building their dig house, and prepare everything for the first season, which would begin in April 1926 and last until October of that year, as Fisher had previously suggested.

FIG. 5. Megiddo team members with Egyptian workmen, fall 1926: Clarence Fisher, with hat on knees in center of photograph; Stanley Fisher is on his left and then Olof Lind; Ruby Woodley is on his right, wearing a hat, and then Edward DeLoach, with two-toned shoes, with Labib Sorial in a fez to his right (courtesy of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago)

Fisher planned to have a trained team in place by the spring. He proposed that their small group should be supplemented by the registrar from his excavations in Egypt, whom he had trained “in careful preparations of notes and plans.” He also suggested that they bring from Egypt “a body of trained workmen, around whom we can build up a body of locals.”60

These trained workmen from Egypt came from the village of Quft, where Petrie had begun this tradition in the 1890s. The descendants of the men whom he originally trained had created a quasi–caste system, in which certain families provided the overseers, while others provided the pickmen, the shovel men, and other necessary workers. According to stories told today at Megiddo, it is these men, eating Egyptian dates during their breakfast, lunch, and work breaks, who were responsible for the date palms now growing all over the top of the mound at the site, but this may be apocryphal. They formed the backbone of the excavation team for the Chicago archaeologists, working for them each season until the end of the excavations in 1939.

When Breasted finally received the official permit for the Megiddo excavations in early August, he forwarded it to Fisher. Two weeks later, the team members left the United States, but on two different ships. On one was Fisher and his twenty-six-year-old nephew (his brother’s son) from St. Louis, who bore the same name but was known as “Stanley.” The plan was to have him serve as their record keeper and accountant/financial officer, in addition to learning how to do archaeology. On the other was Higgins, who would be the surveyor and photographer, along with his wife and daughters, and DeLoach, who was appointed the expedition’s cartographer as well as assistant to Higgins.61 Fisher was the oldest, having just turned forty-nine, but Higgins was only about five years younger.62

The plan was to have these four men begin the preliminary surface survey of the site immediately. Four additional Americans would join them six months later, so that the excavation season could begin as planned in April 1926, with the Egyptian workmen having arrived in the meantime. The four additional men never materialized, however. Only one more team member joined them, the former Yalie named Kellogg, whom we have already met, and who was twenty-eight years old at the time.63

There were no women included among the initial staff; Fisher left behind his wife, Florie, and their seventeen-year-old son, Clarence Stanley, Jr., in the Philadelphia area. Although Higgins brought his wife, Ethel, and their two daughters, the three women chose to live in Beirut, near the American University, rather than at Megiddo; Ethel promptly began teaching first-year Latin to the American schoolchildren there.64

Apart from Fisher, none of the members of the expedition had any actual excavation experience, and only Fisher and Higgins had been outside the United States before. Though we can commend Breasted for having a reasonably multidisciplinary team, insofar as there was an architect, a surveyor, a cartographer, and an accountant among their members, it is truly surprising that there was nobody else experienced in doing actual archaeology. Even Fisher had been trained as an architect rather than as an archaeologist, though that wasn’t all that unusual for the age.

That there were such people available with at least classroom knowledge, and some with actual excavation experience, is beyond question, though. Courses in archaeology, Egyptology, and the like, were already in place in England at Liverpool University by 1904 (established by Garstang) and the University of London (where Petrie had been appointed professor of Egyptology already in 1892). Established curricula were in place even earlier in continental Europe, including at the Humboldt University in Berlin, where Breasted himself had become the first American to receive a PhD in Egyptology, back in 1894. Even in the United States, archaeology courses were being offered at schools, including Bryn Mawr and Smith, as early as 1900.

Furthermore, Breasted could easily have filled his team with pioneering women archaeologists alone, such as Harriet Boyd Hawes, Edith Hall Dohan, and Hetty Goldman. All had directed their own excavations in Greece, Crete, and/or Turkey years before the Chicago team went to Megiddo. It is probably unfair to castigate Breasted in hindsight, given the general tenor of those times, but it is also interesting to speculate as to whether he would do things differently if he were staffing the excavation today.65