CHAPTER VI

“They Can Be Nothing Else than Stables”

The discovery of “Solomon’s Stables” came near the beginning of Guy’s second season, but we need to start earlier than that in order to appreciate what it meant for the expedition. When he had first taken over from Fisher the previous year, in early May 1927, Guy had high hopes that they would find something dramatic.1 So did Breasted. They initially spoke about acting on a proposal that had been made by Fisher, in which they would confine their excavations “to the six northernmost squares on top of the mound and … go down as deeply as possible.” Instead, Guy first continued the practice of opening up as much area as possible, having received permission to hire as many as three hundred workers, as long as he could use them efficiently.2 That would have been a lot of workmen—a force larger than that at most contemporaneous digs—but there were almost never that many available at one time, as it turned out.

Even though, as discussed, his initial 1927 season turned out to be shorter than Guy would have liked, and despite the fact that it was beset by malaria, staffing problems, innuendo, and gossip, as well as the fact that he himself was present only part-time right through the end of August, the Chicago team actually accomplished quite a lot during that first year under his leadership. While they had no major discoveries to report, that year’s work set the stage for the momentous 1928 season. We know this in part from a twelve-page letter that Guy wrote to Breasted in mid-August, detailing their accomplishments to that date, although only part of it deals with the actual digging; the rest is taken up with budgetary and personnel matters.3

This seems to have been the only time that Guy actually sent such a detailed report during the 1927 season. The closest he got at any other time that year was a brief note back at the beginning of the season, from the end of May, in which he simply said: “All goes well meanwhile: clearing of dump area is finished & we have about 100 men clearing exposed levels at the top of the chute. 2 caves on dump area yielded much pottery. Nothing much coming out of the upper dig as yet, of course.”4

Much of the season was taken up with laying down two parallel lines of railway tracks on the mound and setting in place more chutes for getting rid of the dirt and stones that they were removing. There were at least four chutes in use by that point; one of these was a sturdy iron chute that they had ordered from Egypt and which was put in place alongside the old wooden chute that they had been using. This also meant moving one of Fisher’s dumps on the side of the mound and enlarging the space on the eastern slope at the bottom of the tell for dumping. During this process they uncovered more graves and shaft tombs, including some from the Iron Age and others that Guy thought might date to the Middle Bronze Age. One contained a beautiful cylinder seal, perhaps made of lapis lazuli. In all, they found a total of forty-one more tombs during the 1927 season, ranging in date from the Early Bronze Age to the Early Iron Age, in addition to the sixty tombs that had already been excavated by Fisher.5

They also uncovered more of the city wall from the Iron Age levels. This is City Wall 325, previously mentioned, which seems to have been built and encircled the entire mound during what is now called Stratum IV, lasting into Stratum III (Guy’s III and Sub-II). Guy thought that the wall had been built about 700 BCE. He was close; we now know that it was still in use in 700 BCE, though it had originally been built earlier than that.6

On the top of the mound, since the area that they had begun to clear “revealed no buildings of outstanding interest,” Guy decided to dig slightly to the north, where Fisher had already found a number of buildings. In this area, they were following the policy of total excavation, and then total removal, of the various strata, one by one. As Guy noted, for instance, “When the work of clearing on the E[ast] slope was finished, we transferred work to the summit, and moved the level II Temple (?).… We shall shortly, I hope, have the big level III Temple (?) out of the way, and then I hope for something of interest.”7 He was unsure at that time about the identifications of these buildings, but clearly both needed to be moved, or removed, so that the team could get down to the more “interesting” levels, as he put it.

By mid-August, they had already reached in some places what Guy called Strata IV and even V (later renamed V and VI by Lamon and Shipton, in the final publication), “owing to the remains of IV being scanty and broken up” in the area where they were digging. They were also running into stratigraphic problems. As Guy noted, “The levels all over the area of which I am writing are very mixed and run into one another in a manner which demands the closest archaeological supervision while they are being dug, and this seems likely to be the case everywhere on the tell itself.”8 All of that changed, however, in 1928.

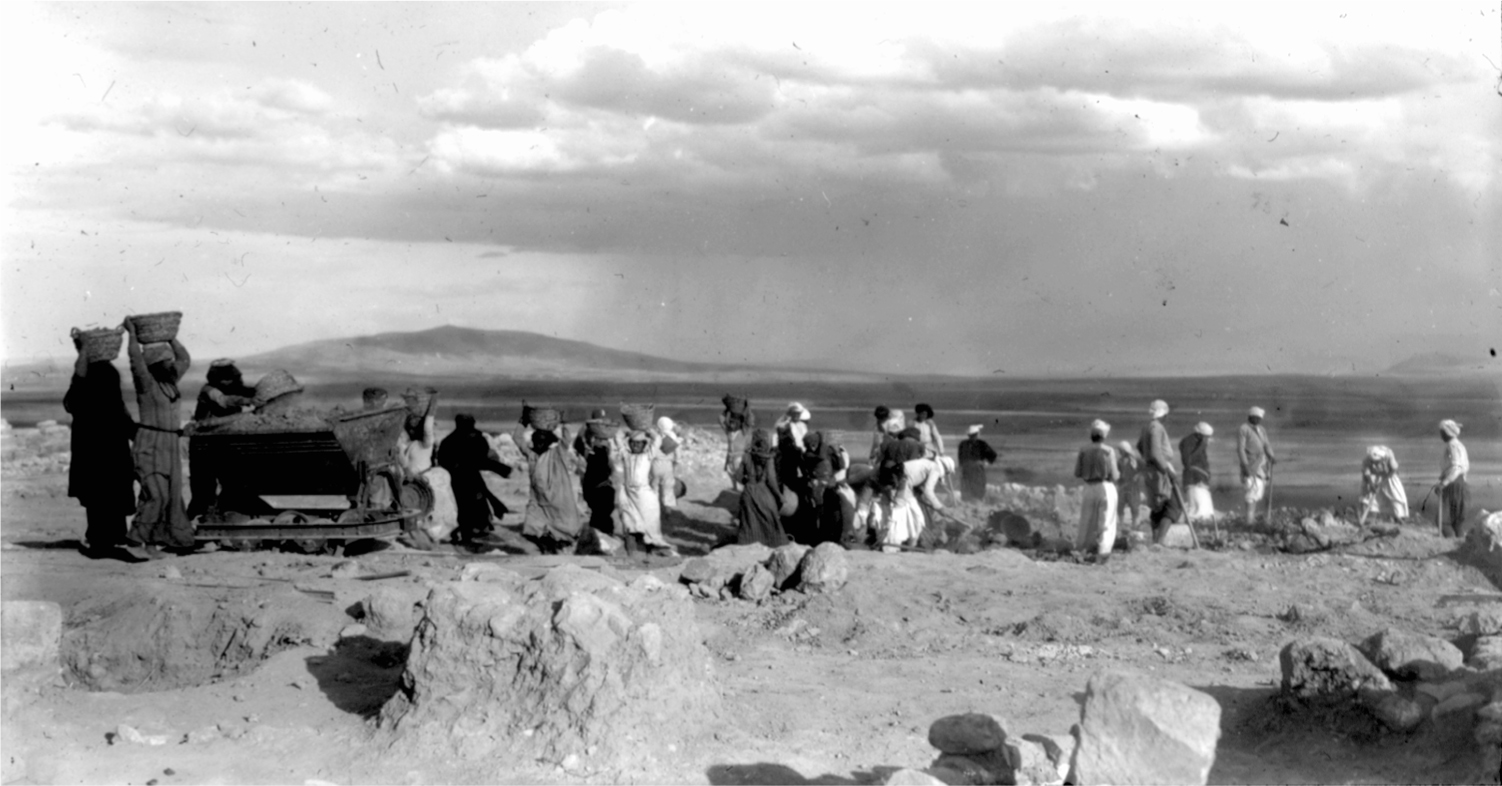

FIG. 18. Megiddo excavations, during Guy’s directorship ca. 1931–34 (courtesy of the Oberlin College archives)

After the Egyptian workmen arrived in late April 1928, they began work at the northern end of the tell, in order to clarify some points and questions left over from the previous season.9 The initial discovery of “Solomon’s Stables” came a few weeks later, just a month into the season. It was at the time of transition between the two surveyors, for Terentieff arrived on 3 June, while Wilensky left two days later, on 5 June. Guy sent the cable announcing the discovery of the stables to Breasted on the day in between (see the prologue, above). However, the first parts of the stables had apparently come to light sometime earlier, as Guy later told Breasted.10

Guy sent the complete details, in a very long letter full of news, at the end of June, several weeks after a division of their finds to that point had been made with the Department of Antiquities.11 This was the type of letter that he was supposed to send once a month but instead ended up sending only once, or sometimes twice, a season … and sometimes not at all.

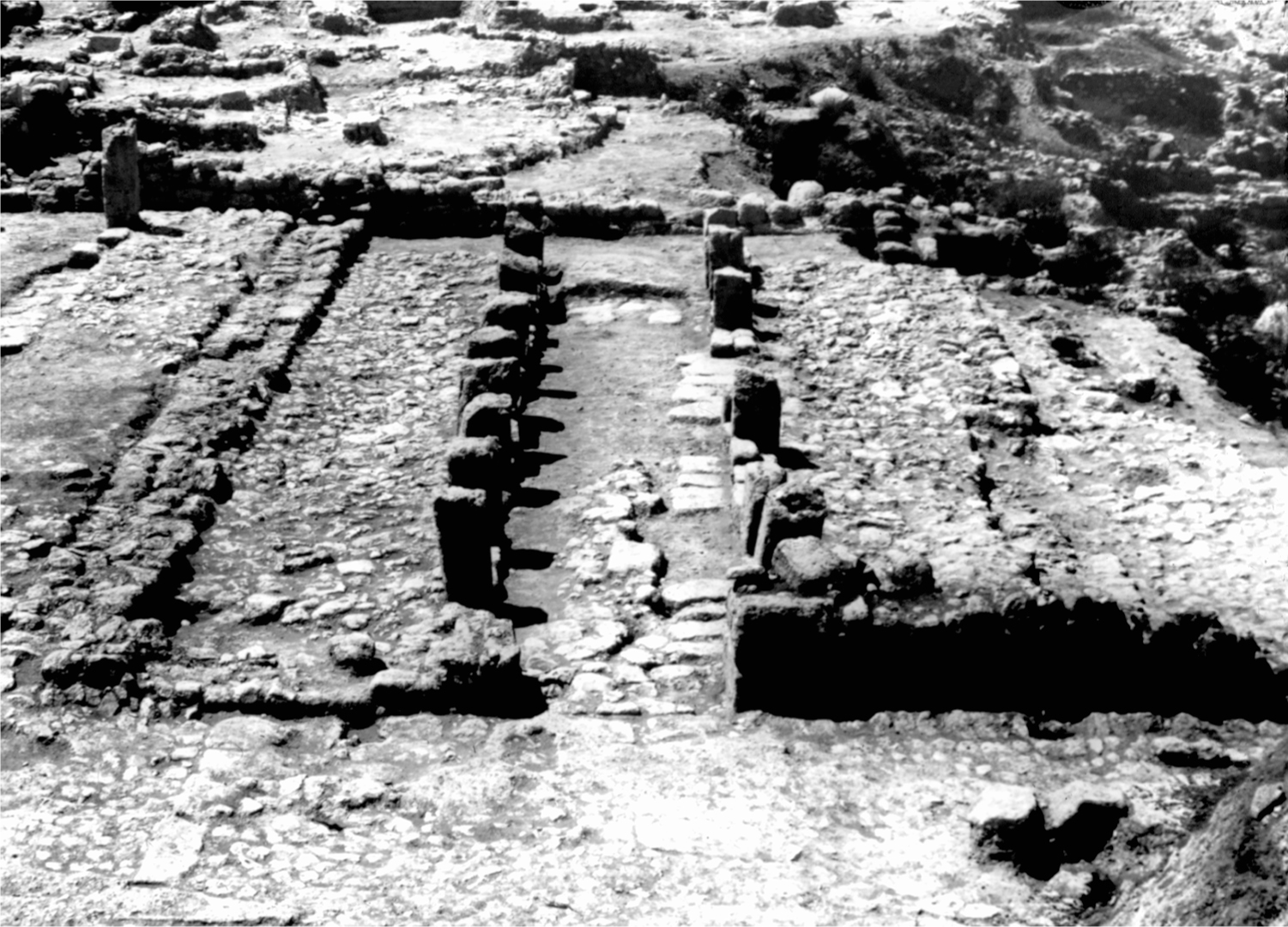

FIG. 19. Portion of northern stables found by Chicago team, June 1928 (courtesy of the Oberlin College archives)

After describing their continuing clearance of City Wall 325, including the fact that there were rooms built up against its inner face, Guy finally got to the important matter of the stables. He wrote: “Our big find, of course, is the great complex of buildings which covers practically the whole of Squares N12 and N13. They can be nothing else than stables, and very good stables too, with room for somewhere about 150 horses. The ‘standing stones’ have no religious significance whatever: they are nothing more or less than hitching-posts, and lots of them have still got the rope holes unbroken.” He thought that there were 12 passages within the stables, with room for 12 horses within each passage, for a total of 144 horses (rather than 150).12

In large part because of these discoveries, Guy asked the draftsmen to begin drawing their plans at a scale of 1:200, rather than the previous 1:100. This resulted in smaller renderings of the buildings and other remains, but they were able to get much more of the site, and the squares that they were excavating, onto a single working plan. This, in turn, permitted them to easily see how everything was connected, even remains that were some distance apart, as Guy reported to Breasted.13

Guy also noted problems with Fisher’s previous methods of recording and registration, complaining that they were pretty theoretical and hard to actually use. He said that others elsewhere, such as at Beth Shean where Fisher had previously worked, had difficulties with them as well, so he had modified them accordingly.14 All of these changes made it easy to better record the discoveries that they were now making.

In early July, Guy elaborated on his previous remarks to Breasted, stating that the stables appeared to be “composed of several units divided from each other by common party-walls. Each unit consists of three passages—the central passage a real passage, the two flanking passages rows of stalls in which the heads of the animals faced inwards so that they could be fed and watered easily from the central passage.”15 By the time the New York Times articles about the stables appeared in August,16 the number of hypothesized horses that could fit into the stables had been reduced to 120, but the rest of the details remained essentially the same.

Each stable was a tripartite arrangement, consisting of a plastered central aisle with a cobblestone aisle to either side. In each of the side aisles, the stalls were arranged in rows with a manger in front of each horse, separated by massive stone hitching posts. Each of the stable buildings that they eventually uncovered had the same plan, usually consisting of at least five such “stable units.” Guy was completely correct about the food for the horses brought in via the plastered central passage, although it now seems that they were probably taken outside for watering.17

Guy also said that they had found grain in one of the stables, which he was submitting to the Department of Agriculture for identification. However, if it was ever done, the results of the analysis seem never to have been reported anywhere.18

Similar structures had been found at other sites, such as Tell el-Hesi and elsewhere, where they had also been dated to the time of Solomon, but nobody had previously been able to identify them. The proper identification of these buildings has, in fact, been the source of continuous debate for most of the last century. While most archaeologists now agree that these are in fact stables, others see them as storehouses or barracks, or as fulfilling some other unidentified purpose. Guy was certain from the outset that they were used as stables, at least initially, when they were built during Stratum IV. However, as he told Breasted, “the stables were re-used in [Stratum] III partly as stables (we have the late mangers in places) and partly, I believe, as dwellings.”19

FIG. 20. Model and detail of “Solomon’s Stables” by Olof E. Lind and Laurence Woolman (courtesy of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago)

As it happens, the most recent expedition to the site, by Tel Aviv University, has uncovered yet more such structures, in the same northern area where the Chicago excavators first found theirs. Their findings have settled the debate in favor of Guy’s identification of them as originally built and used as stables.20

However, there is one other problem—the date of the stables. Guy was sure that they were built during the time of Solomon, as indicated by his initial cable in early June, but he confessed that there were also some stratigraphic difficulties. While he told Breasted that “our Stratum IV, in which our stables occur, is to be pushed back beyond the time of Omri and Samaria to the time of Solomon,” he also noted that “III follows closely on IV, and there is practically no difference between the pottery of the two.… All the Megiddo strata are, so far as I have dug them, mixed up with one another in a way I have seldom seen elsewhere, and III and IV are peculiarly difficult to disentangle in many places.”21

Guy did not realize that the two levels were much later in date than he thought they were. It is now generally accepted that the stables were first built during the second half of Stratum IV, in the period now called IVA. Many archaeologists have dated this phase to the ninth century BCE and the time of Ahab and Omri. It also fits quite well because of a mention on the Monolith Inscription, erected over in Mesopotamia by the Neo-Assyrian king Shalmaneser III, which says that Ahab brought two thousand chariots to the Battle of Qarqar, which was fought in Syria in 853 BCE. However, following the additional excavations by the current Tel Aviv Expedition, a number of scholars would now go even lower and argue that the initial construction of the stables dates to the first half of the eighth century, during the reign of Jeroboam II.22 Either way, it is now clear that this city of the stables, our Stratum IVA, was not built by Solomon.

Not knowing any of this at the time, Guy continued to believe that he had uncovered Solomon’s Stables. He spelled out his reasoning to Breasted, writing: “Horses and chariots were of great importance to Solomon: it would be natural, taking into consideration the importance of Megiddo, the traditional connection of the Plain with chariots, the convenience of its situation for dealings with Kings of the Hittites and of Syria, that Solomon should make a Chariot City of it.”23 Of course, horses and chariots were of great importance to the kings who came after Solomon as well, so the same arguments could apply to them, but that went unsaid.

Overall, in large part because of the discovery of the stables, the 1928 season proved to be much more successful than the previous one. As a result, Guy stated rather melodramatically, “Our current discovery of a city of the tenth century B.C.—well planned and built as a homogeneous whole—leads me to recommend to you that the whole of our plan of campaign should be changed.”24

To his mind, Stratum IV had been “conceived and built by one authority”: Solomon. Therefore, as he put it, they now had the opportunity—or, rather, almost a duty—of excavating the entirety of what he thought was one of Solomon’s largest cities. He noted that previous excavators at sites elsewhere had dug right through strata and cities dating to the time of Solomon almost without a second thought, but that at Megiddo they were lucky to have realized what they had come across before excavating farther.25

Guy therefore asked Breasted for permission to uncover the entire town, thereby continuing their practice of what we would call today “horizontal archaeology,” in which the entire stratum is revealed before any of it is removed. It was for this reason that they needed to acquire the entire mound of Megiddo, he said, and not just the portion that they had been renting and excavating up to that time. And it was for that reason Breasted readily agreed to purchase the land from Mrs. Templeton.26

Guy sent the workmen home because of the rains in November 1928,27 but up until that time they worked in fifteen new squares on the top of the mound, removing the surface strata. Guy noted that “there is very little of Stratum I remaining … the first buildings we find belong chiefly to II.” He was pleased about this, he said, “because of the relative unimportance of [Stratum] I.” Such an attitude would not be tolerated in archaeology today, where every stratum is seen as important in terms of the history of an ancient site. They also weren’t finding many ancient remains or artifacts in the upper level, which delighted Guy, since it meant that they could dig quickly. He did realize that he shouldn’t be admitting to such feelings, however, noting parenthetically, “(is this wicked, [coming] from an archaeologist?).”28

Guy also said, probably trying to get on Breasted’s good side, that he had cleared a bit off the South Slope of the tell, by Square T9. Here he had found City Wall 325, and just below it some pottery from the earliest part of the Iron Age, dating just after 1200 BCE, he thought. Just eighteen inches (half a meter) farther down, they uncovered some Late Cypriot pottery, so he thought that it wouldn’t be long before they reached the period of Ramses and then the Amarna period. The “Thothmes” stratum, as he put it, would not be far below this. “There is thus,” he concluded, “no great depth of debris to be excavated … and I know that you will be glad of this.”29 Unfortunately, Guy could not have been more wrong; it would take another seven years of digging, and a different field director, before they got down to the Egyptian levels that Breasted had long anticipated.