CHAPTER X

“Either a Battle or an Earthquake”

Guy sent a brief note to Breasted in late June 1934, about a week after the “May incident” had taken place but still several weeks before he sent the sordid letter marked “Confidential” that eventually led to his firing. In the note, he said that he was shipping to Chicago a small bronze statue-base that they had found in Stratum “VII lower,” as Guy called it, which had Egyptian hieroglyphics inscribed on all four sides. He said that when they showed the statue-base to Alan Rowe, over at Beth Shean, Rowe thought that the cartouches were those of Ramses II.1

When the statue-base arrived in Chicago and was carefully cleaned, it turned out that the cartouches actually belonged to Ramses VI, who ruled ca. 1140 BCE. It took until the end of November for the experts in Chicago to determine that reading, but once they did, Breasted sent a cable to the team at Megiddo with the news:2

BRONZE STATUE BASE BEARS NAME RAMSES SIXTH MIDDLE TWELFTH CENTURY LETTER FOLLOWS BREASTED

Breasted was ecstatic. He immediately began researching and writing up the statue-base, musing about it in the letter that he subsequently sent to Lamon.3 Although his publication of the bronze statue-base did not appear until 1948—in the pages of Loud’s Megiddo II volume, thirteen years after Breasted’s death—it is clear from the similarity of the sentences in the letter to Lamon that Breasted wrote the article almost immediately. Loud simply added a footnote on the object’s findspot, stating that it was found under a Stratum VIIB wall in Room 1832, which would indeed be Guy’s “VII lower” level. Loud noted that the statue-base was obviously intrusive to its context, which it undoubtedly was, given the difference in dates between the object and the findspot—we now know that Stratum VIIB dates to the fourteenth century BCE, while Ramses VI ruled two hundred years later, in the twelfth century BCE.4

FIG. 31. Ramses VI bronze statue-base (after Loud 1948: fig. 374; courtesy of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago)

The most likely explanation for this is that Guy’s workmen must have found the statue-base in a pit, which they failed to discern while they were excavating. If so, such a pit would have been dug down into this earlier phase by an inhabitant of Stratum VIIA, just as it was ending ca. 1130 BCE (or perhaps even during the next level, VIA, before it too was destroyed). However, we shouldn’t be too accepting of Loud’s statement regarding the findspot since he was not yet at Megiddo when it was found back in 1934.

Loud also misstates when it was found, saying that it was “autumn 1934,” when all of the correspondence clearly indicates that it was found late in the spring and had already been shipped back to Chicago for conservation by midsummer. As a result, tempting as it is, we should be careful about using this particular object to date any of the levels at Megiddo, from VIA back to VIIB, even though it is now one of the most cited objects in the scholarly literature about these periods at Megiddo.

However, all of this is getting ahead of our story about the archaeology during these years from 1932 through 1934, so we’d ideally want to return to 27 March 1932, when the actual digging began for the spring season that year.5 Unfortunately, it does us no good to return to that specific date, or even to the weeks thereafter, for, as mentioned above, there is no information about the archaeology in any letters sent by Guy back to Chicago during the next few months. They dug at the site until mid-December, but it was not until January 1933 that Guy finally told Breasted what they had been finding.6

During both the spring and fall seasons in 1932, Guy said, they had concentrated on the tell itself, removing more of the later remains in the southern portion, between Schumacher’s trench and the water system, and then toward the city gate. These remains were “scrappy,” as he called them, and reused older walls in many places, which meant that the team had to proceed carefully in order to untangle them properly.7

In the end, they managed to retrieve a “definite town-plan over a large area, with four parallel streets.” This must be our Stratum III (Guy’s Sub-II), since he also says that “there are still some houses later than this overlying it in the northern section.” Of the various possibilities, only the plan of Stratum III fits this description of having parallel streets.8

While the identity of the inhabitants of Strata II and I at Megiddo remains debated—specifically, whether there were Neo-Babylonians here as well as Persians, as seems most likely, or exclusively Persians9—it is now clear from the archaeology that Stratum III belongs to the Neo-Assyrian period, and that it was the last time the site itself was of any importance.

The Neo-Assyrian rulers had been recording their battles and triumphs against the kings of Israel and Judah from the time of Shalmaneser III in the ninth century BCE; we know from their inscriptions (and those of others) that biblical figures such as Omri, Ahab, and Jehu actually existed.10 By the time of the Neo-Assyrian kings Shalmaneser V and Sargon II in the middle and late eighth century BCE, the northern kingdom of Israel and its capital, Samaria—not far from Megiddo—had been overwhelmed and incorporated as a province of Assyria. The deported Israelites, many of whom were taken away to Assyria in what is now modern Iraq, became known as the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel.11

Megiddo itself was likely conquered a decade or so earlier, by Tiglath-Pileser III in about 734 BCE, perhaps rather easily since there are few, if any, signs of destruction at the end of Stratum IVA. By the time of Sargon II, a new phase began at the ancient site, namely, Stratum III, which incorporated some of the elements of Stratum IVA, such as the stables, as well as new constructions. The architectural plan, including bathrooms and horseshoe door sockets, reflects the fact that Megiddo now served as one of the Neo-Assyrian regional capitals, when it was known as “Magidu.” We even know the name of one of its Neo-Assyrian governors, Issi-Adad-Aninu, who ruled in the year 679 BCE, during the reign of King Esarhaddon.12

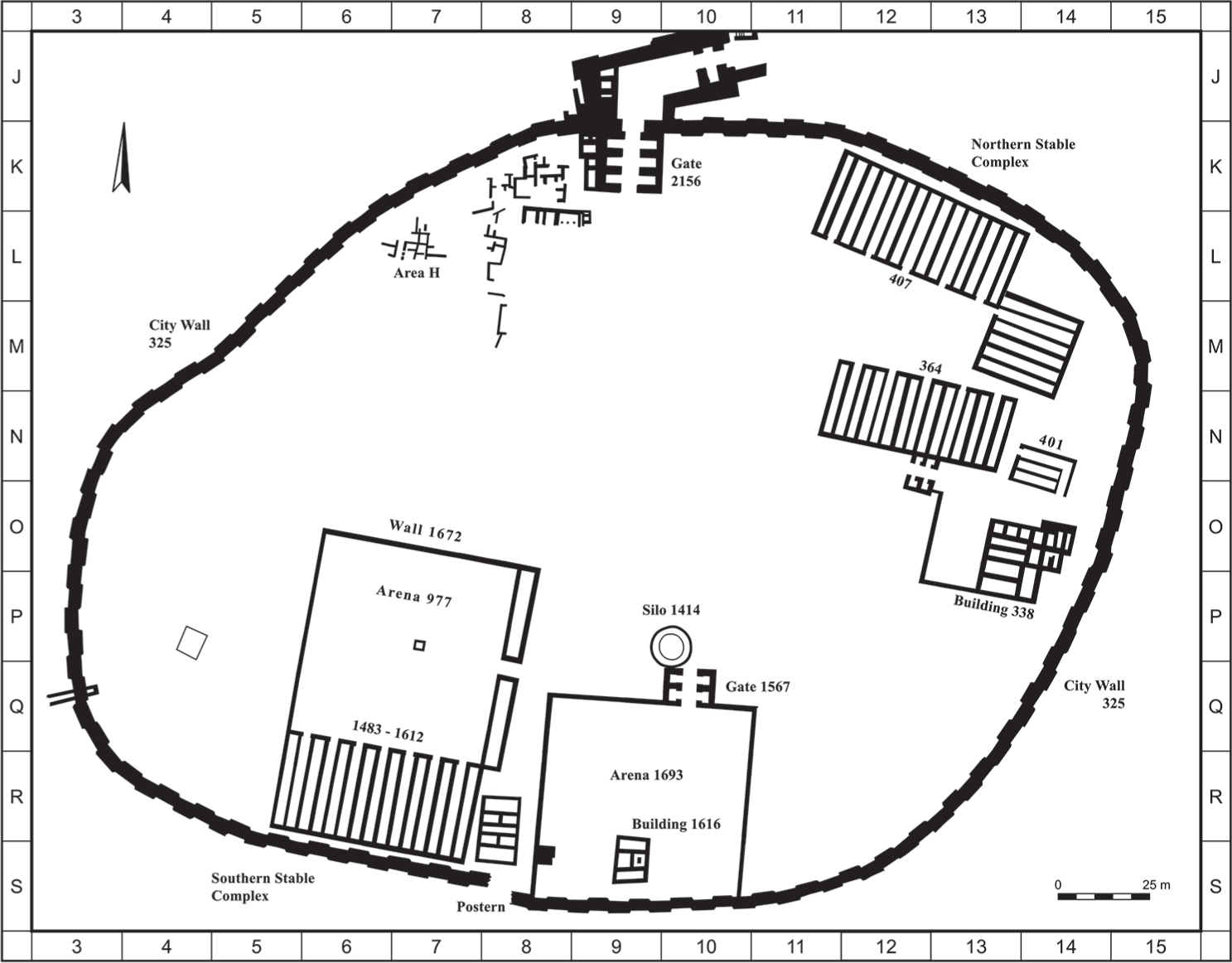

FIG. 32. Plan of Stratum III, view looking west (after Herzog 1997: 256, fig. 5.35; courtesy of the author)

We can, therefore, finally describe what an actual city at Megiddo—that of Stratum III—looked like, since this was the first layer with a cohesive plan that the Chicago excavators uncovered. There were east-west and north-south streets both separating and connecting well-built blocks of houses, primarily within the central area of the city. The water tunnel was in use at the western edge of the city. There were also two open-court palaces/residencies (Buildings 1052 and 1369) and another large (probably public) building (490) at the northwestern edge of the city, located to either side of the city gate and protected by City Wall 325, which still encircled the city.13 These palaces/residencies, or perhaps they were simply administrative buildings, look like those built in Mesopotamia, in the heartland of Assyria. The Chicago excavators removed one of the palaces, in an effort to reach deeper levels, but the other is still visible today.

The population of the city at this time most likely consisted of people imported from elsewhere in the empire, as was the practice of the Neo-Assyrian kings, who were known for “de-porting and re-porting” the various peoples whom they conquered.14 From this point on, from the late eighth century BCE until its demise in the mid-fourth century BCE, Megiddo was incorporated into one large Near Eastern empire after another: first the Neo-Assyrians, then the Neo-Babylonians, and finally the Persians, each of whom dominated the entire region for a century or more, one following the other, as has been noted above.15

Guy thought that the “town of the parallel streets,” our Stratum III, dated to “roughly 500–700 BC,” on the basis of the pottery that the team found.16 This is, to his credit, quite close to our current thinking, ca. 780–650 BCE. He also noted that they were getting more pottery, from all over the mound now; in some cases, they were collecting as many as thirty to fifty baskets of pottery from a single location. Of course, Guy described almost all of this as being rather dull, but he thought that the other material they were finding—on the East Slope and in the tombs—would be of interest to people.

In particular, Guy remarked upon a lecture that he had heard Dorothy Garrod give at the Prehistoric Congress in London the previous summer, on the material that she was finding in the Carmel Caves. He thought this bore comparison with some of the material that they were finding on the East Slope, and believed that it might date back to the Natufian period, at the very beginning of occupation at the site. He was planning to ask Engberg, since he had some training in anthropology, to take a look at the skulls in consultation with Sir Arthur Keith, who was in charge of studying all of Miss Garrod’s skeletal material. He also wondered what Breasted thought of shipping the skeletal material to London so that they could work on it there. As it happened, the material instead went to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, a year or so later, as already described.

Since that is the extent of Guy’s discussion in his letters of the archaeological details from the 1932 season, it is perhaps fortunate that we also have a few additional details in the report that Guy was required to submit to the Department of Antiquities. This was published in 1934, in volume 3 of QDAP.17 Here he reported that more tombs, of various periods, had been excavated on the East Slope, and that these tombs, along with those found in 1927 and in 1930–31, were to be published together in a single volume. He also noted that a number of “habitations—some caves, some houses,” as well as pottery belonging to the fourth millennium BCE or even earlier, had been discovered on the East Slope. Seven ceramic stages had been discerned, he said, and would be published in a volume by Engberg and Shipton, which did subsequently appear later in 1934.18 However, the remainder of his published comments had to do with excavations that were conducted on the top of the mound up through the spring of the next season, in 1933, and seem to have more to do with that year, so we will return to them below.

We also know that Guy provided details for a volume that Breasted had been asked to prepare on the work of the Oriental Institute, which was published in 1933. However, these do not shed any additional light on the work done at the site in 1932, which was one of the least remarkable seasons for the Chicago team at Megiddo.

Guy took to heart Breasted’s order to send monthly reports, beginning 1 June 1933. This is the first such report that we have for the year, but since the spring season came to an end six weeks later, in mid-July,19 it serves as the only information that we have for the entire first half of the year, in terms of archaeology.

Guy said that he had had trouble hiring enough local workmen at the beginning of the spring season because of the harvest, but as of 1 June he had “217 on the pay roll.”20 Even given the fact that Breasted had requested that the labor force always be above 200, this is still an astonishing number compared to today’s excavations. Most now utilize college-age students, rather than paid laborers, and few digs today have more than 100 team members at a time. Those who do employ skilled workmen normally hire only a few, and for limited duration, for today such labor can cost upwards of $90 per day per person. Of course, those were different times, and wages are not comparable, but still, imagining the workers lining up to be paid at the end of the workweek in 1933 invokes what must have been a fairly amazing sight.

In any event, Guy said that they had been following Breasted’s new commands and had been limiting their work to the new area on the southern end of the mound. They had removed all of the surface remains, which had been categorized as coming from either Stratum I or a catchall “Latest Remains” (which seems to have been anything from the Roman period onward). They had then prepared all of the Stratum II remains and taken an aerial photo, after which many of these ruins had been removed as well. They had also extended the tracks of the “Central Railway”, so that they could use it as well as the “Southern Railway” in this area of the mound.21

In addition, they had cleared up a large building in Q10 that had been first excavated by Schumacher, and had found another wall belonging to it running off to the west for at least forty-five meters, with no sign of stopping. Since it was “of excellent workmanship,” Guy was looking forward to revealing the rest of it. He thought it might connect to two walls located several squares away, in O6, and that it might turn out to be a big palace enclosure.22

And, finally, a large circular structure that had been revealed in Square P10 turned out to be a huge grain silo, lined with stone and seven meters deep.23 This large underground silo is on the stopping point of every tour group that visits the site, since it is at the top of the modern tourist pathway leading up to the current summit of the mound, at the junction where most such groups then turn to the right in order to get to the entrance to the water system and descend the staircase to walk through the water tunnel.

FIG. 33. Plan of Stratum IV (after Franklin 2017: 88, Fig. 1; courtesy of the author)

They had also found a lot of pottery, as perhaps was to be expected, as well as a number of small objects, including fibulae (pins), arrows, beads, amulets, figurines, and stone bowls. There were also a few scarabs, Guy said, but these would have to wait for the Egyptologists to identify them.24

In early September, while still on his summer break, Guy sent Breasted the second of the four “monthly” reports that he wrote that year. He spent much of the letter discussing “two great enclosures, each over sixty meters across.” These, which were in the same area where he had found the long and well-constructed wall during the spring, could be seen in an aerial photograph that Guy also sent to Breasted. They had well-built walls and floors made of white lime. The western one turned out to be a large courtyard attached to another set of stables, to match the ones that they had found farther to the north back in 1928.25

Guy sent two more “monthly” reports back to Breasted that year, one in early November and the other in early December. Both were concerned primarily with the continuation of the clearance of the large western enclosure. By the time of the November report, they had exposed a stable of five units within the southern part of the enclosure, with twenty-eight stalls in each, meaning that it could have held 140 horses. Counting the stables that they had found previously, during the 1928 season, Guy noted that they now had accommodations for well over 400 horses at the site during this period. He interpreted the rest of the enclosure as a “parade ground,” which is still considered a possibility, though it is even more likely that it simply functioned on most days as a courtyard for training the horses.26

By the time Guy sent his December report, they had removed most of the floor of the “parade ground” as well as the floors of the stables in the western enclosure. Underneath they found a stratum of “pinkish, burnt mud-brick,” but Guy noted in passing that “there are also buildings—small rooms intermediate between mudbrick and stables.”27

There is a little bit more detail in the report that was published in the 1934 volume of QDAP, the official publication of the Department of Antiquities, as previously mentioned. Here, Guy noted that the excavation of the entire mound had continued into the spring of 1933, with the resulting exposure of the town with four parallel streets, remarked upon above. After May 1933, however, he reported that they had restricted excavation to an area measuring 150 m × 100 m, located “on the high ground in the southern part of the city.”28

He now provided more details about the western enclosure that they had uncovered, which he said measured 90 m × 60 m—consisting of the “parade ground” (60 meters square and covered with white lime) plus the stable of five units at its southern end. The nearby eastern enclosure was simply 60 meters square, because it didn’t have the additional stables. Although they still needed to remove some of the later buildings on top of it, they could already see a large area covered by a white lime floor and a gateway in the northern wall. This, he noted, “is the building described by Schumacher as a palace [his “Palast”].”29

In his December letter to Breasted, Guy added that they had been working quickly, with over three hundred local workers in the gang at one point, but that now they were down closer to the two-hundred-person mark. Although there had been some rain, they were still digging away, and continued to do so until 22 December, according to the letter that Guy subsequently sent at the end of January.30

FIG. 34. Reconstruction of Stratum IV structures in Area A from the northwest by Concannon (courtesy of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago)

About the same time that the skeletal material was shipped to Washington, DC, the spring 1934 excavation season finally began in early April. Guy had given in to Breasted’s repeated pleas and was “going deep in, as you want.” He thought that the area of the eastern enclosure, where they had begun digging the previous year, was the most promising, and so they had staked out an area that measured sixty meters on a side in the vicinity of Square R9; this was later dubbed Area CC. We “shall hope to reach Egyptian strata before closing,” wrote Guy. Engberg echoed the sentiment, writing optimistically, “I believe we should see the Ramesside level before the end of June.” Lamon went even further, writing in early May, “Our slogan for this season is still ‘Thutmose or bust.’ ”31

By mid-April, Guy was able to tell Breasted that below the eastern enclosure they had discovered the foundations of a building that measured about twenty-three meters on each side. City Wall 325 passed over part of it and was actually—in this area—built of finished stones that had been taken from the building. Guy noted that the demolition had been almost total, writing, “This building may well have been a palace, but, as luck would have it, not a single thing remained in it, for the ancient destruction had been thorough except for the foundation course; I am hoping for a foundation deposit under that.” These remains are all that are left of what is now known as the Southern Palace, more usually referred to as Palace 1723.32

FIG. 35. Removal of bronze vessel hoard in Locus 1739 from Stratum VIA (after Harrison 2004: fig. 99; courtesy of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago)

In the 1960s, excavating below the level of the northern stables at Megiddo, the Israeli archaeologist Yigael Yadin found another palace—known as Palace 6000—that dates to the same time as Guy’s Southern Palace (1723). This additional palace was later further excavated by members of the Tel Aviv Expedition, including the present author, from 1998 to 2007. These two palaces are now assigned to what is known as Stratum VA/IVB (which will be discussed further below, in our final chapter). At the time, Yadin thought that it was this level that dated to Solomon, rather than Stratum IVA as Guy had believed. However, Yadin’s hypothesis has now also fallen out of favor, and most scholars date this level to the time of Ahab and Omri in the ninth century BCE. In part this is because of correlations with the site of Samaria, including masons’ marks that Guy first noticed could be seen on the fine foundation blocks of the Southern Palace.33

Guy also said that in some places they had dug into the burnt mudbrick layer that lay below the Southern Palace. This burnt city is the level that we now call Stratum VIA. “In this there seem to be more things preserved in situ than in any of the later strata,” Guy said, “so I am hoping to get something useful out of it.” He also noted that they were working with only 160 laborers at the moment, since there wasn’t room for any more in the limited area that they were now excavating, but even these few were producing enough finds to keep the pottery people and the surveyors busy.34

Sure enough, just two weeks later, at the end of April, Guy telephoned the Antiquities Department in Jerusalem to tell them that they had come across a group of twenty-seven bronze objects that were in extremely fragile condition. He had ordered paraffin wax to be poured over them all and then surrounded the entire group with plaster of paris, so that they could be moved to Jerusalem for the conservators at the department to work on.35 A few days later, he sent them off, along with a letter to the director of antiquities, which read in part: “On 25 April we found in locus 1739 (Square R10) a group of about 27 bronzes—bowls, platters, axes, spearheads, etc. They probably belong to a mudbrick stratum, now in course of excavation, which … may turn out to be dateable to shortly after 1200 B.C.”36 He was off by more than two centuries, since Stratum VIA is now thought to belong to the tenth century BCE, but he was not wrong about their importance.

Excitement ran high at the dig. May wrote to a colleague, asserting that they had “reached a stratum destroyed by violent siege and fire by the incoming Philistines, probably circa 1190 BC.” He described the city as blackened by the conflagration and noted that they had found the skeleton of a young girl, who still lay where she had been crushed by a falling wall. Of the greatest importance, though, was the large palace that they had found, which was “probably built by David.”37 However, May was conflating two different levels here. First of all, David is unlikely to have built this Southern Palace (1723), which belongs to Stratum VA/IVB. Second, incoming Philistines probably did not cause the destruction of the burnt city (Stratum VIA). In fact, May himself had already helped to determine the most likely cause of the destruction of that level—an earthquake.38

FIG. 36. Crushed skeleton and pottery in Locus 1745 from Stratum VIA (after Harrison 2004: fig. 83; courtesy of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago)

Irwin had arrived at the dig by that time—actually more than a month earlier—and he now wrote to Breasted with a detailed description of what they were finding. He seems to have been the first to record the possibility that they were looking at the effects of an earthquake: “The other matter is the interest which May and I are finding in an upheaved course of large stones … just north of our present area of excavation and east of Schumacher’s trench. It seems inconceivable that it has resulted from anything but earthquake.”39

Irwin, ever the Hebrew scholar, suggested that it could perhaps be identified with “the great earthquake to which Amos refers” (Amos 1:1), which the Bible says took place during the reign of Jeroboam II. If so, Irwin continued, it could possibly help to solve “the vexed question of the date of Amos’ prophecy” and even the date of “the fall of Jehu’s dynasty.”40 Would that it were so easy! As Irwin himself admitted, “There are still very weak links in the argument,” and indeed there were, in terms of the dating, for Amos’s earthquake was probably almost two hundred years later, in the mid-eighth century BCE, rather than toward the end of the tenth century BCE, as this destruction has turned out to be.

Guy expanded on all of this later, in his end-of-the-season report to Breasted, which he sent on 13 July after having stopped for the season on 28 June (and, apparently, having also stopped writing the monthly reports in the interim). It is worth reproducing in its entirety, so that the excitement of the moment is captured:41

There had obviously been a disaster of some sort in VI, of which the fire was a culmination, and that disaster may have been either a battle or an earthquake. In the course of it, a number of people had perished. Some skeletons were found crushed under walls in positions of obvious agony … but a number of others had been buried.… They had, however, been buried very summarily, with no orientation and practically no furniture; the most we found was a bowl over a man’s head, and a number of sherds covering the skeleton of a child of perhaps 12. A few people had been stuffed into pots, but not in the Middle Bronze fashion. It looked as if survivors had come back after the catastrophe and had left where they were those bodies which had been hidden by fallen walls but had hastily buried those who were visible.

Guy, like May and Irwin, was also in favor of the earthquake theory for the destruction of the VIA city. He pointed out that several of the walls were cracked, and a few of them had been completely displaced and thrown out of alignment. He also noted that “no weapons, such as arrowheads, were found in any of the skeletons, and very few in the whole of the area excavated.” Finally, he—almost casually—mentioned “the presence of quite a lot of burnt wood, some pieces being posts or other structural articles but others almost certainly planted trees,” adding that they had kept samples for examination. He ended his description by concluding that “the disaster, whatever it was, had been pretty sudden, for most of the rooms contained very large quantities of pottery in situ, and this gave us a most representative collection of types.”42

And then, again almost nonchalantly, as if he had nearly forgotten about the earlier excitement, he added: “To return to stratum VI: though we did not get a great number of interesting small finds, we had one real piece of luck. This consisted in digging up a fine collection of bronzes …—spear-heads, axe-heads, bowls, plates, jugs and strainers—about thirty pieces in all, stuck together in a pile. It looked as if somebody had made them into a bundle with the view of getting away from the city with them, but had had to drop them in his flight. They were not in a house, but in an open space. I have handed them to the Department for treatment, but this has not yet been completed.”43

I have to agree with all of them regarding the earthquake hypothesis, after having been a part of the later Megiddo excavation run by Tel Aviv University, where we excavated part of this same layer in 1998, with the same results, including finding crushed skeletons and walls cracked and thrown out of alignment.44 An earthquake is most likely, in my opinion, especially since (a) there are no arrowheads or other weapons either in or near any of the bodies, nor any cut marks on the skeletons, such as would have been made by a sword; (b) some of the bodies were crushed by falling walls and roofs; and (c) the walls were moved and misaligned by a force greater than that which is usually caused by humans, even those equipped with a battering ram (which is unlikely to have been wielded inside the city proper).

For those who believe this was caused by enemy attack, on the other hand, it is conceivable that the culprit could be Sheshonq/Shishak, although this seems unlikely. Other recent suggestions have included King David and the Israelites or simply Israelites without David, either before or after his reign.45 However, none of the arguments for human destruction are particularly persuasive, especially since they cannot account for any of the points just made, and so I think the evidence points more toward an earthquake.

The date of the destruction is also still problematic. While we’ve seen that Irwin wanted to date it to the mid-eighth century on the basis of the biblical reference in Amos, Guy thought that it fell somewhere between 1100 and 1000 BCE.46 The recent Tel Aviv excavations of VIA levels in their Areas H and K (Levels H-9 and K-4) have now provided radiocarbon dates that should theoretically help to resolve the dilemma, but the range is still too great, for they suggest that the destruction took place sometime during a fifty-year period between 985 and 935 BCE.47 This would be either just before, during, or toward the end of Solomon’s reign, using the generally accepted dates of ca. 970–930 BCE for his rule. However, David Ussishkin has proposed a slightly earlier date for the destruction of VIA: sometime between 1020 and 950 BCE, basically from just before David’s reign until just after (Ussishkin is following the generally accepted dates for David as 1005–970 BCE).48 In short, the range of dates is wide enough to allow those who want to see VIA destroyed by humans to suggest it could have been done by anyone from David to Solomon to “Israelites” to Sheshonq.

It has been suggested upon occasion that VIA was an Israelite city, but by far the majority of scholars agree that it was actually the last Canaanite city—at least in terms of material culture and, therefore, ethnicity. The most recent exhaustive study, by Eran Arie, now the Frieder Burda Curator of Iron Age and Persian Period Archaeology at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem and formerly a staff member of the Tel Aviv excavations, concludes, “One can safely argue that the bulk of the inhabitants of Megiddo VI were Canaanites.”49

Forgetting the absolute dating for a moment, and just going with the material culture of the pottery and other artifacts, it appears that Stratum VB, the city of scrappy ruined houses that comes immediately after the burnt city of VIA, is the first undeniable Israelite city.50 Given its impoverished nature, it seems unlikely that this would have been the city fortified by Solomon, as described in the biblical account, or a city that Sheshonq would have bragged about conquering, and yet, since we have ruled out Strata IVA and VA/IVB so far, we may not be left with much choice. In fact, Ussishkin has recently specifically suggested that VB is Solomon’s Megiddo, though this remains unproven.51

However, there is another possibility. Already back in 1996, even before all of the new radiocarbon dates became available, Israel Finkelstein had suggested that Megiddo VIA should be dated to the tenth century BCE and the time of the United Monarchy.52 It is not impossible that the mudbrick city of Stratum VIA was in fact the city that dates to the time of David and Solomon, even if the material culture indicates that the majority of the inhabitants were still primarily Canaanite. It would have been an impressive city, worthy of mention in both the biblical and Egyptian accounts. Alas, the one thing that we know for certain at the moment is that the complete destruction of VIA was an Armageddon for the inhabitants, regardless of whoever or whatever caused it and whether or not it was the city of Solomon.

In any event, below this level, Guy told Breasted, “we came to a stratum of rubble houses … and in this begin to appear scraps of Cypriote milk-bowls and [jugs] as well as of Mycenaean pottery.” They also found numerous beads and pieces of faience, as well as Egyptian scarabs, perhaps from the time of Ramses III. This they began calling Stratum VII, dating it quite properly to the Late Bronze Age.53 Deep in this level—“VII lower” according to Guy, which is now interpreted as Stratum VIIB, as mentioned—they also uncovered a Hittite stamp seal originally made in Anatolia, which was inscribed with the name “Anu-Ziti” and his title of “charioteer”—he was perhaps a royal emissary from the Hittite king.54 It was here that they also found the bronze statue-base of Ramses VI, which Guy first mentioned to Breasted in late June, as he was shipping it back to Chicago.

The team also dug in two other interrelated places that we know of during that spring season. The first area was inside the actual water system itself. In a letter written at the beginning of May, Lamon said that during the previous fall season, in 1933, they had been doing some additional work in the vertical shaft leading down to the tunnel and suddenly realized that the tunnel did not end (or begin, depending upon one’s orientation) at the shaft, but rather “extends beyond it in the general direction of the middle of the Tell.”55

The other area was just inside the city gate, in Square L9, where they dug in order to investigate a sizable depression that they thought might be the top of another vertical shaft. Lamon wrote, in that same letter sent to Breasted in early May, that he had previously thought this “indicated the existence of a second, quite independent and somewhat earlier water system probably not dissimilar to the present, twelfth century water hold; but, since this depression falls on or near the extended line of the newly discovered tunnel, it is not unlikely that the two shafts are connected.”56

Lamon therefore requested permission from Breasted to conduct further exploration in both areas, though he warned Breasted that this might prove to be fairly expensive. He proposed several different options for conducting the excavations, primarily concerned with how to move the dirt that they would encounter, and thought that the end results would justify the expense.57 Breasted was intrigued, but hesitant about the cost. He wrote back at the end of May, asking Lamon to send him a memo with the probable expenses listed.58

Upon receiving this letter, Lamon put ten men to work in the newly discovered continuation of the tunnel, in order to get some idea of what would be involved in following it out further, so that he could base his estimated expenses in reality. To his consternation, “By noon the same day we reached the end of the tunnel—a ‘blind alley’ only five meters long!” He attributed the extra portion of the tunnel to an error on the part of the ancient engineer, who had miscalculated the distance necessary to meet the bottom of the shaft, since the tunnel was slightly inclined rather than perfectly horizontal.59

He also noted that their related investigations of the “sizable depression” inside the city gate had produced inconclusive results. “If this depression does mark the top of a vertical shaft,” he wrote, “it is entirely separate from the present water system.” To explore it further would cost approximately twenty pounds, he thought, but in the end, this further exploration was put on hold.60

Interestingly, however, in connection with this same approximate area, Irwin wrote to Breasted, also in late May, describing some chats that he had just had with Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie. He wanted to relay the fact that Petrie was “very anxious that we dig just west of our city gate, or at least run in a trench to see whether we locate thick walls of a palace. He cites his own success by following the principle that the palace would be on the coolest, most breezy part of the tell.” Breasted was intrigued, writing back: “I note with interest the suggestion from my old friend Petrie. It shows his old keenness for the practical realities of any situation. There may be something in it, and I shall write Guy about it.”61 In fact, Breasted never did write to Guy about it, for he fired him first, but Petrie was absolutely correct, for it was in this precise location that Gordon Loud, the next field director, found the palace of Stratum VII, complete with its treasures of gold and ivory, which we shall consider in an upcoming chapter.