Hitting .300 is as simple as learning the foundation of hitting. Coaches and instructors often make the mistake of complicating what is a very simple process. We tend to confuse kids by getting them to think about a bunch of technical jargon, when the basic foundation will do the job.

I’m going to give you a conventional and solid basis for everything you will do as a hitter, from day one. When you get to the higher levels—high school, college, and pro ball—and you are already pretty good, then it’s okay to experiment with different stances if you think they will help you see the ball better.

To get started, here are all the basics of hitting that lay the groundwork for success:

Swing a bat that feels comfortable to you. You don’t want to grab a bat so heavy that it will force you to drag it through the strike zone, or one so light that it feels like a whiffle bat. Pick something that feels good. Get a bat in your hand that allows for a comfortable swing. We’ll talk more about bats and batting gloves in chapter 2.

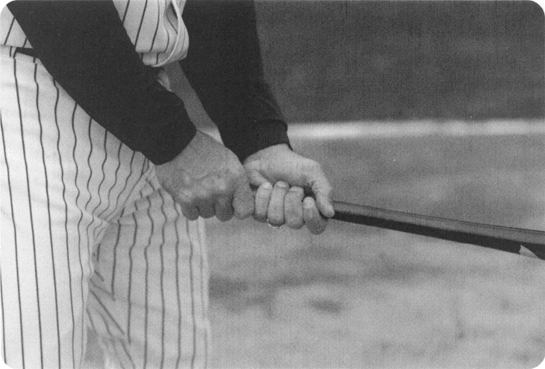

The bat must stay in your fingertips to get the hands moving free and easy.

Just before the pitch: The goal is to stay relaxed and ready to go.

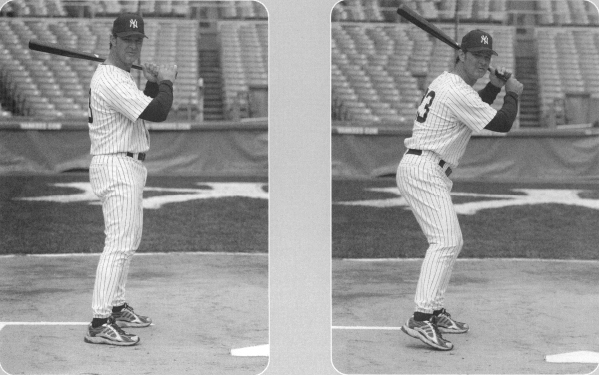

When you stand in the batter’s box, you want to be comfortable. I favor a shoulder-width stance for its simplicity and its ability to help me stay balanced. I always tell kids:

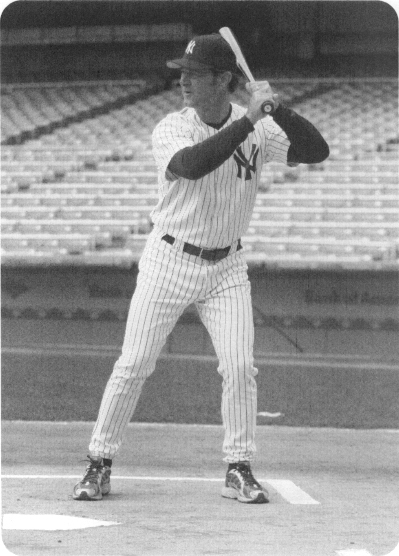

Make sure you are balanced on the balls of your feet, as this will allow you to swing the bat with consistency. The goal is to be able to take the bat from Point A to Point B. This movement starts with a simple stance.

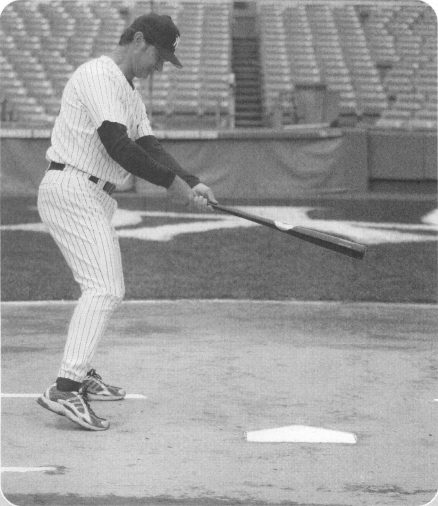

If you were to draw a straight line from where your feet are aligned, the goal is to stride toward the pitcher. If I stride open—if I’m stepping back away from the pitcher—it will force my front-side shoulder to come out, and then I open my hips early. Next thing you know, I’m dropping my hands and I won’t be able to take a straight path to the ball.

For me, the key to success is to take a straight path to the ball, to get back to basics. This first move causes a chain reaction. If you follow that straight path, your hips stay square and at that point you can take the bat directly to the ball.

Remember that the shortest distance between two points (from the bat to the ball) is a straight line. Any deviation from the straight line will make your swing longer. That’s when you hear comments like “He is dragging his bat through the strike zone.”

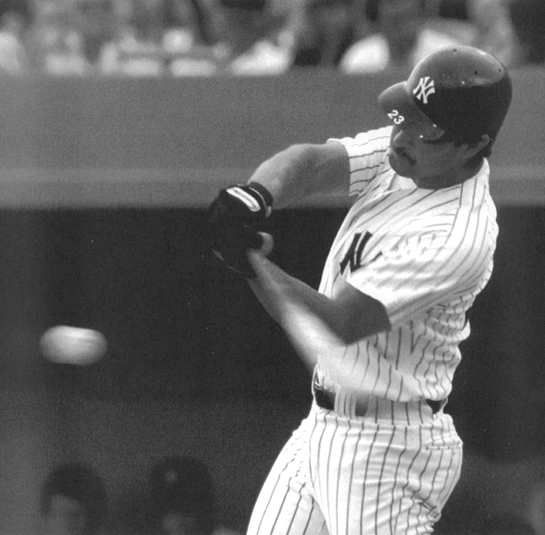

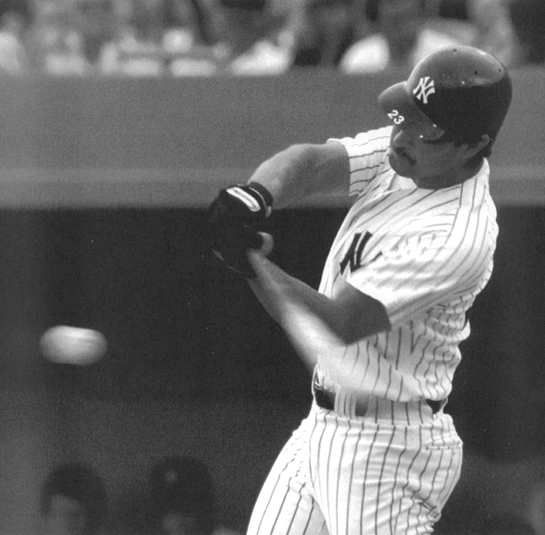

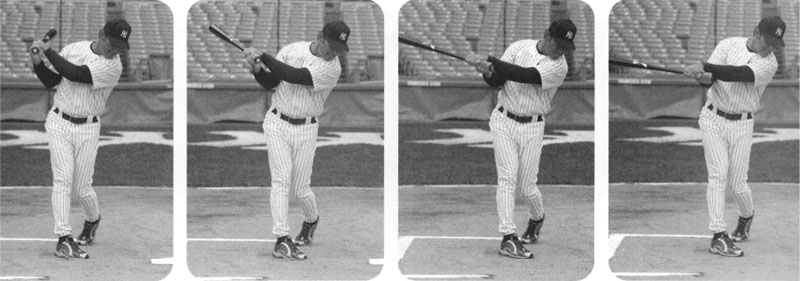

(From left to right): Once again, I’m staying relaxed until the pitcher is ready. As the pitcher is getting started I pick my hands up and get ready to start my swing. The swing gets started with a slight shift of weight to the backside.

You do see guys with long swings make it to the big leagues, and they tend to be power hitters who strike out a lot. Their swing is not as consistent; they are more hot and cold-type hitters.

Ideally, you want a shorter swing that goes directly from Point A to Point B because shorter is quicker. If pitchers throw harder, a longer swing will give you less time to make a decision. We’re talking about time and distance: A swing on a straight line puts your hands straight to the path of the pitch. If you have a longer swing, though, your path is not quite as direct and that little movement will end up causing you trouble.

My advice is to lay the bat on your shoulders; as you pick the bat up your hands are in a solid position to hit the baseball.

Now that we’ve talked about the feet being fairly straight in the stance and the stride moving in a straight line, the next element is proper hand position. My advice is to lay the bat on your shoulders; as you pick the bat up, your hands are in a solid position to hit the baseball. The goal is to get your hands in a nice, relaxed position to start the swing.

You want to have a shoulder-width stance; a good, balanced position, aligned with the release point—the zone around which a pitcher will release the baseball; and your hands in a nice, relaxed position on the bat.

This rule applies to almost any athletic activity. The objective is to create some type of momentum. A cat that’s on the prowl is in a coiled position before it strikes—same thing with a snake that’s coiled. They are essentially moving in reverse—before striking at their prey.

For hitting, there needs to be a little bit of lean back to initiate the swing before you stride forward. You’ll see some hitters do a little step back, which is often called the “toe-tap.” Chipper Jones of the Atlanta Braves does this, and it works well for him: He steps back and then goes forward. I don’t teach the toe-tap, but you have to do something in your swing to get your weight to go back before you move forward—and obviously it works for Chipper.

Think of this triggering mechanism as a bow and arrow: You have to draw back the bow slowly and then let it go so that the arrow can hit its target. Same thing with hitting: It’s a slow start to your swing, with a lean to trigger the movement—the coiling of the snake—and then a smooth move forward. As you pick up your front foot, you should be able to stand on one leg or move forward or glide toward the ball under control. If I pick up my front foot and fall forward, it’s a sure bet that my balance is off.

(From left to right): A side view of the swing: Take a slight movement back to initiate the swing. You should now be able to stay balanced on the back leg, so as you move back and your front foot comes off the ground you will be able to stand in at the plate in a comfortable, ready position.

Here’s how it all works together in sequence: I’m relaxed and ready as I step into the batter’s box with a shoulder-width stance. I’ve got the bat in the position where I picked it up off my shoulders, the pitch is coming, I pick up my foot, and I have to go back before going forward or I’ll be unbalanced at the outset of the swing.

Shift, carry, and glide your weight from back to middle to the point of contact as you keep your head and eyes down on the ball. Swing down on the ball as if you’re chopping down a tree with an ax—taking the knob to the ball, keeping the barrel of the bat above the hands.

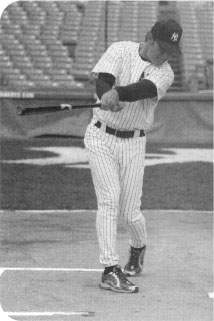

I prefer “finish your swing” to the concept of the “follow-through” on the swing. You always hear about “staying through the ball,” and that simply means to leave your head down and finish your swing. Don’t look up to find out where the ball went. It feels natural, but it cuts your swing off. The goal is to hit through the ball and then look for it after making contact.

When you hear baseball coaches talk about “to it and through it” all they really mean is to finish the swing. Swing to the ball and swing through the ball. If you are trying to chop down a tree with an ax, you never stop short at the point of contact. You want to chop as if you are cutting all the way through that tree.

It’s the same deal with swinging a baseball bat. If you stop the swing and look up as soon as you hit the ball, you end up falling backward. Now, if you swing through the ball, your transfer of weight keeps you going. You’ll rotate through the ball and finish your swing.

As you start the swing (four photos above) the goal is to work down on the ball, which leaves the bat flat in the strike zone. Again, we want to finish the swing before we look up for the baseball to assure that we swing all the way through the ball.

I would always stay on the back line of the batter’s box. My feeling was that the back of the box gave me more time to see the ball and make adjustments. Notice here how my hips are square to home plate.

This is a personal deal. I liked being in the very back of the box. My feeling was that the back of the box gave me more time to see the ball and make adjustments.

Tony Gwynn would always stand in the middle of the box, with his front foot in front of the plate and his back foot in back of the plate. Other players like being even with the plate.

Some hitters will move up in the box to hit the breaking ball. But Tony Gwynn will tell you that moving up or back in the box is the biggest mistake you can make—he was a creature of habit, and preached staying in a comfort zone that’s predictable every time you hit, so you know what to expect.

Like I said, I would always stay on the back line of the box, but I would move closer to or farther away from the plate depending on who was pitching. I would move closer to the plate against a pitcher like Jamie Moyer, who throws a good change-up and specializes in off-speed pitches. That kind of pitcher likes a lot of room, and that’s why I would stand as close to the plate as possible and force everything to be right in my hitting zone. I do not want off-speed pitchers to have any space to throw the ball from inside to outside; if he wants to come inside, a guy like Moyer would almost have to hit me with the pitch.

If, however, I was facing a power pitcher like Randy Johnson, I would move farther away from the plate to give him more room—not because he’s going to hit me, but because I want to cover only one half of the plate or the other. I’m not going to try to cover the entire plate against a power pitcher. I’m only going to hit those pitches that are going to end up being strikes on the inner half of the plate. If Randy can throw two strikes on the outside corner, he’ll have me in a 0--2 hole, and now I’m going to have to fight to get a hit. But up until I’m in that 0--2 hole, I’m still going to try to cover half the plate.

As I reach for the outside part of the plate, the goal is to be able to touch the outside corner; if you bend your knees, you should always have proper plate coverage. A solid swing that is fundamentally sound will enable you to adjust to a wide variety of pitches and locations.

If you don’t stride straight and stay balanced, you’re going to have a lot of trouble making contact against a lot of different pitches. You may still be able to hit a pitch that’s on the inside corner because that’s in a zone you can still reach, but most of the time you will hit that pitch foul. Now you know why I favor solid, straight-line mechanics, as they allow you to hit more pitches in more zones of the plate.

Your mission is to learn how to hit in a way that allows you to handle more pitches from a variety of styles of pitchers. A solid swing that is fundamentally sound will enable you to adjust to a wide variety of pitches and locations. Pulling off the pitch or having a long swing will make it very tough for you to hit pitches in certain areas of the plate. The mechanics of your swing will often dictate what pitches you can and cannot hit. Many hitters never figure out how to hit pitches in all locations, but they’re smart enough to lay off the pitches they can’t handle and instead focus on the pitches they can hit. You either learn to hit a certain pitch or you quit swinging at it—that’s the mark of a smart hitter.

Remember that very few pitchers have pinpoint control. If a pitcher can throw the ball where he wants to all the time, he’s going to win almost every battle—assuming, of course, his stuff matches up with his precision. Every hitter has holes in his swing; it comes down to whether the pitcher has the control needed to locate his pitches with consistency.

If you stride too far, your head starts to move and you won’t get a good look at the pitch.

An inside-out hitter keeps his hands inside the baseball. It’s a great way to look at what Tony Gwynn talks about, when he says to “Take the knob of the bat to the ball.” You can still pull the pitch but you have to keep your hands inside the ball, so your swing must be short and compact.

I like the concept of the inside-out swing, or hands inside the ball, because it keeps a player focused on the straight-line mechanics that are the foundation of hitting. Let’s say you get a pitch to hit in the middle part of the plate. If you have a good swing—and you are making sure your hands are inside of the ball, you can hit the ball in any of three or four different places and it will look as if you hit the ball on the nose. You can hit a bullet to left-center, a bullet to dead center, a bullet to right-center, and probably hard down either line. In each case, it would look like you hit the ball right on the nose.

Remember that you have to hit the ball where it’s pitched; that’s basic. So the one solid swing we’ve been working on will allow you to hit the ball to left field, center field, or right field.

The hands go back slowly; you go directly to the ball; and you hit it in different spots, depending on the location of the pitch, to spray the ball to all fields.

The pitch that nips the outside corner has to come farther to you, and so you’ll have to hit it back farther, or deeper, toward you at the plate. A left-handed batter will shoot that pitch toward the left; a right-handed hitter will shoot that pitch toward the right. The ball you hit up the middle is a ball you hit a little farther out in front of you, and it’s located toward the middle part of the plate.

Pulling the ball is the last thing you’ll learn, and it is the toughest thing to do properly because you have to hit the ball so far out in front. You’ll still be able to keep your hands inside the ball that’s on the inside part of the plate, but you’ve got to hit it farther out—you have to stay closed longer, to get to that pitch and pull it to the left or right.