Donnie is a great coach because he’s willing to put the time and effort into helping his players. I don’t know where I’d be without him at my side.

Before you learn how to become a .300 hitter, you must make a commitment to two things: working hard and having fun. If you enjoy playing the game, it’s no big deal to spend an hour hitting off the batting tee, taking soft toss or batting practice, or fielding ground ball after ground ball to get better.

In all the years I played professional baseball, I never met a player who didn’t have to work hard to be successful. But what’s the point of learning a skill if you don’t get enjoy what you’re doing? It has to be something that you love, that you have a passion for—and forget the shortcuts.

You have to put the time, effort, and concentration into getting better at any skill. That’s basic. But you must have a passion for that skill, sport, or activity. Without passion, you will never have the competitive fire that allows you to get better and better.

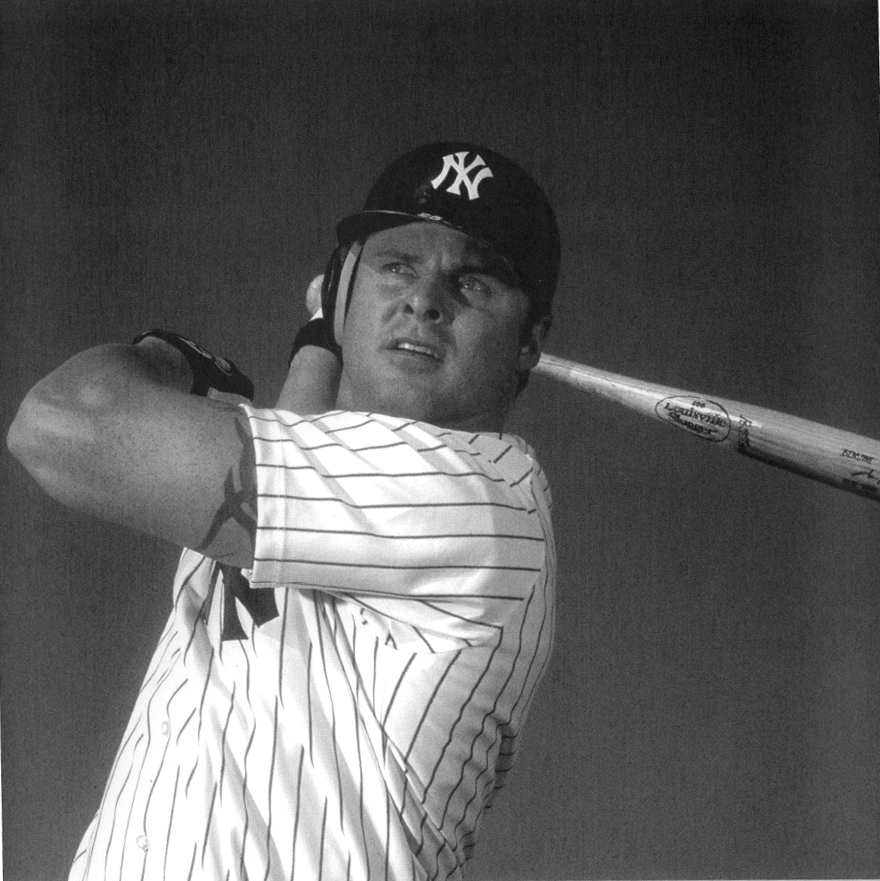

I like this photo because you can tell that I hit the ball the opposite way—my balance is solid.

I was a three-sport athlete in high school and loved to compete to win. Besides being on the baseball team, I excelled at basketball and football, while I also played tennis and racquetball. I enjoyed all of these sports and had no plan to pursue a career in baseball until the summer of my freshman year in high school.

I was fifteen years old and damn lucky to be on an excellent American Legion baseball team in Evansville, Indiana, that even included some college players. Back in the seventies each American Legion post had the pick of the best players from the top four or five high school programs in the area, and the competition was intense. There was a kid by the name of Mark King who was pitching against us for Kentucky—we had a pretty good rivalry going in American Legion ball between teams in Kentucky and Indiana.

The Kentucky--Indiana game was the night before King signed his deal with the Cincinnati Reds, and a huge crowd from two states watched Indiana win 2--1. I went 2-3 with a couple of doubles against King. And that one ball game was the beginning of my commitment to baseball.

All of a sudden I was receiving letters from big-league scouts, on official letterhead. I can tell you that it’s pretty exciting to open your mail as a teenager and see the logo of the Cincinnati Reds or New York Yankees.

As each baseball season would roll around, I’d work on building hand strength with wrist exercises, and hit in the cage and in the practice and in games. I loved every minute of high school baseball. I had a coach in Quentin Merkel who was a work-oriented guy.

And the hard work paid off with winning a state championship when I was a junior (the team went 30--0). We lost in the state championship game the following season, with a 29--1 record—we had won fifty-nine games in a row before that loss in the title game. After the 30--0 season, a lot of coaches would have been smug and satisfied, but he challenged each player to get better and work harder:

“If you feel like you’re the best player in town, strive to become the best player in your region. If you feel like you’re the best player in your region, strive to become the best player in Indiana. If you feel like you’re the best player in Indiana, strive to become the best player in the nation.”

On June 5, 1979, the New York Yankees selected me in the nineteenth round of the amateur draft. I signed right out of high school. When I look back on it and reflect on my skills, here is what the scouts were looking at when they dropped me down to the nineteenth round:

It would have taken a skilled scout to have been able to project that all of those tools would improve over time, with hard work and dedication.

The hidden x-factor in drafting a prospect is: How motivated is this player to be his best? Most teams could not have guessed how hard I was willing to work to make it to the big leagues. Major-league organizations spend more time researching this type of intangible element now than they did when I was drafted. They ask questions like: What kind of kid is this? Does he work hard? Is he able to make adjustments? Would he be willing to learn a new position and work hard at being good?

It is a fine line between success and failure. The talent pool is so close that a lot of guys have the capability and talent to make it to the top. The thing that sets these prospects apart is the commitment to working hard physically and mentally, and to understand the nuances of the game.

I had an easy transition, going from high school to pro ball. I got to play baseball every night and hang around during the day. I thought it was the best thing to do in the whole world. And I was even getting paid to play a game that I loved.

There were several roving hitting instructors in the Yankee organization when I first arrived, but the person who made the biggest impression on me was Mickey Vernon, a former first baseman with the Philadelphia Phillies.

Mickey was great for me because he wasn’t the kind of batting coach who tried to make major changes in my swing. He would simply watch what I was doing in the cage, and it was often unclear what he was thinking. But I remember something he said at the time that made a big impression: “Donnie, don’t let anyone tell you that you can’t play in the major leagues just the way you are as a hitter right now.” He gave me confidence that I could make it to the big leagues, even if I didn’t have much power for a first baseman-outfielder. He wasn’t telling me I had it made right then and there, without putting in even more hard work. All he was saying was that I shouldn’t let anyone take away my God-given gift that I had developed to put the barrel of the bat on the ball.

I prefer batting gloves that fit tight, with no loose fabric hanging off the end of the fingers. Look for gloves that are perfectly aligned to the contours of your hands.

MICKEY VERNON: I met Donnie for the first time in 1979. He was playing for Oneonta in short-season Class A, the first rung of the ladder in the New York Yankees farm system. Donnie impressed me right away with his bat control. He made good contact and was spraying the ball all over the field.

The following season, the Yankees sent him to Greensboro, North Carolina, to work on playing left field. I can tell you that his hitting was already very good.

My theory on hitting instruction is that you should watch a young hitter to figure out what the scouts saw in him in the first place. After you evaluate a player, then—and only then—would you consider making a change in his swing or his batting stance. My rule is to adjust and fine***tune rather than change what made the kid a good hitter from the get-go. Donnie didn’t need to be told too much because he had the natural ability to put the bat on the ball.

Then I went to Columbus [AAA] to help Donnie with his fielding at first base and with his hitting, which was pretty darn good. I remember sending a report on him to the Yankees that year [1982], in which I described him as a future All-Star who would lead the league in batting one year [Mattingly won the AL batting title in 1984 with a .343 mark]. I also said he was capable of hitting fifteen to twenty home runs, once he learned how to pull the ball [Mattingly hit more than twenty home runs five times during his thirteen-year major-league career].

Look at the numbers! He had a tremendous swing and a great career because of how hard he worked to improve, evolve, and adjust.

I remember working with him on his fielding at first base: I’d organize infield drills, where I’d hit the ball to certain spots and he’d have to run over to the first-base bag, turn, and make an accurate, strong throw to second base. He would work for hours to improve his fielding, and ultimately he became the best first baseman in the American League for the better part of a decade.

Donnie is a great role model for kids. His experience and intelligence makes him a great teacher of hitting, and he’s a terrific person and a hard worker to go along with his skill and talent. You do have to work hard to get to the major leagues—trust me—and Donnie worked for all the success he enjoyed in his career.

I remember also working with Rex Hudler, a teammate of Donnie’s in Greensboro, and “Hud” and all of the other young players knew that Donnie was a very special player.

REX HUDLER: Donnie and I played together in the New York Yankees farm system. He was a nineteenth-round pick, and I was a first-round pick a year later [1980], and yet Donnie made it to New York before I did. By the time I got to the Yankees in 1984, Donnie had a rock concert going on—he was the best hitter in baseball from 1984 to ’89.

But in those early days in the low minors, the thing that set Donnie apart was the kind of person that he was. He would look at me, shake his head, and tell me: “Hud—you are going to be a big leaguer.” His wife, Kim, was very nice, too, and I was so happy for both of them when Don was called up at the end of the 1982 season.

The thing you can learn from Donnie is that he had to work hard to learn how to pull the ball and hit to all fields with power. When he signed, he was figured on as an outfielder. But with hard work he turned himself into a Gold Glove first baseman. He had soft hands, a big first baseman’s glove, and an intense competitive desire to be the best

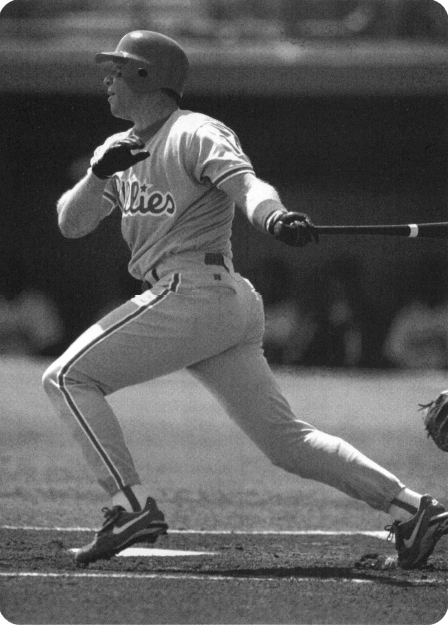

It looks like another good swing from Rex “The Hud Dog” Hudler. It looks like he’s hit the ball well, his head is down, and he’s in balance.