CHOQUEQUIRAO: CRADLE OF GOLD

Tell the white men that to get where we live, the roads are so bad that they will die on the journey, and that we have no chicken eggs to give them.

Message from a village headman

to the Comte de Sartiges in 1834

CORTÉS, ARGUABLY THE GREATEST of all South American explorers, was famous for never being able to stop exploring. Having conquered Mexico and then advanced down much of Central America, he didn’t seem able to enjoy the fruits that these discoveries brought – land, wealth and even a Marquisate – but instead launched various punitively expensive trips up the western coast of Mexico towards what is now California in an attempt to find a supposed city of gold. He found nothing, bankrupted himself and died struggling as a result. The waters between Lower California and Mexico are still known as the Sea of Cortés as an ironic epitaph. Likewise Captain Cook was unable to resist the lure of a third and, as it turned out, terminal voyage, even though he had been offered a well-earned retirement in Greenwich.

Our surprising success in finding Llactapata had not satisfied our need to keep on with our own modest expedition. If anything, it was a spur, a first real hit of the heady drug of discovery, and I could understand better how Bingham had been so propelled from one lost ruin to the next. What also had begun to intrigue me more and more was not the idea of finding ruins, but of tracing the Inca roads between them. Perhaps I’d always felt the same about mountains, where I’d never particularly needed to get to the top but had always enjoyed the passes.

The more I walked them, the more the Inca paths became fascinating in their own right, deliberately over-constructed objects of beauty that were a statement as clear as any work by Christo or Richard Long about a love for the ground they walked on. They were emphatically not simple ways of getting from A to B. Nothing was more remarkable than to emerge on some hidden plateau at 10,000 feet and see a gleaming stone road or causeway laid ahead of you, apparently going nowhere, a testament not only to the Incaic skill in stonemasonry but to their extraordinary, almost symbiotic feel for the mountains themselves.

We determined to follow some of the routes that the early explorers had taken in the hinterland beyond Machu Picchu, even more remote than Llactapata, and in particular, to get to the distant site of Choquequirao. This famous and romantically isolated ruin lay by the side of the Apurimac river and we decided to go there not by the only known open route, ascending from the river itself, but by hacking our way across the jungle and the mountain watershed between the Urubamba and the Apurimac basins and seeing what roads lay between. This was a route that Bingham had considered impassable and not attempted, but which an intrepid French aristocrat called the Comte de Sartiges had taken in 1834, with fifteen Indians cutting a path for him through the dense shrub.

David Drew and some of the Cusichaca archaeologists wanted to study the sites in the higher Santa Teresa valley, which lay on our route, and so we arranged to work together with them for a while before then heading off on our own towards Choquequirao.

We arrived with the archaeologists at the Santa Teresa railway station feeling rather proud of ourselves after the Llactapata discovery. Vincente was even prouder of having taken us there, and I stood him numerous drinks as he regaled the villagers and a slightly disgruntled Juan Ganchos with the tale.

This time we had to see the Chief of Police for the various permissions we needed both for a larger party and for our own later trip across to Choquequirao. He turned out to be an affable man starved of company, who ushered us into a study dominated by an enormous gold-and-green banner above the desk: he explained that the banner was for the police football team. Our paperwork had been prepared by Ann Kendall, an expert in Peruvian bureaucracy, and was impressive enough for him to stamp it no less than three times with different seals.

The Chief offered us the use of their football pitch to sleep on. As an alternative to the bedbugs and sleazy hostel we’d experienced before, this was welcome, although the pitch was so compacted by heavy playing that it was still uncomfortable. One advantage of having the archaeologists along, however, was that our supply of alcohol had now increased to manageable proportions. After a few rum-and-apple-juices, even the football pitch couldn’t stop me from sleeping.

It was good to have some new blood. Along with the archaeologists came Vaughan Fleming, a photographer attached to the Cusichaca group to document finds, but whose real passion in life was natural history. He had already researched a monograph on Cretan flowers and was now making a collection of Peruvian fungi for the British Museum. As we travelled up the Santa Teresa valley together, he would point out both exotic and startlingly ordinary mosses. In a charming way Vaughan looked a bit like an insect anthropoid, with an engaging, alert head and long, thin legs. He was a fund of strange but true zoological stories, from the rainforest conditions along a section of Welsh coast to the migratory habits of Monarch butterflies, one of which landed on our sandwiches but could equally well, according to Vaughan, have been seen off the Isle of Wight.

I was starting to have problems with a wisdom tooth. This may have been due to the constant supply of Army ration sweets, or perhaps Rosilla’s theory about the effect of altitude on the gums was correct, but it was difficult to focus on much else. I increased my supply of coca to try to numb the pain, although by now I was on the equivalent of three packs a day.

That night, at a small village called Miscabamba, I slept atrociously in the tent and staggered out early. The tent was anyway no place to outstay your welcome. J.B. had been in economical mode when he had bought it and the man in the shop had assured him that a three-man tent would be fine for us. What he hadn’t told him was that this was a mountaineering tent, and so ‘three-man’ in the sense that you could get three into it if you were over-nighting on a narrow ledge, or your life depended on it. It was not designed to live in for months on end. As a punishment Roddy and I had consigned J.B. to the very bottom end, where he slept cross-wise with only the occasional understandable complaint about the smell of our feet.

The night had left me debilitated and in considerable pain. The trek up the valley was unrelenting and I looked enviously at the few ponies we had, which were carrying supplies rather than people. By the time we came to Colcapampa, where the various head-valleys met, I was getting behind. David came back for me and gave me a hand with my pack. As the nearest dentist was several days away at Cuzco and going there would mean aborting the whole trip, there seemed no alternative but to persevere.

Colcapampa had one great natural asset – some hot springs that bubbled up from the rock-face right by the path. I stripped off and washed. Holding my head under hot water seemed to help the pain, for no good logical reason. My hat was unable to conceal any longer what was becoming a serious hair problem, and I used a sachet of Johnson’s Baby Shampoo that I’d purchased from the shack down by the railroad. Halfway through the operation, a column of Quechua ladies wound down along the track and passed by without a glance at the unusual spectacle of a pale gringo in his Y-fronts, lathering up his hair.

There were some small farming communities at the head of the valley, and that Sunday they had a fiesta, with plenty of chicha blanca, a drink inherited from Inca times with a wheaty, not quite fermented taste, like a speciality Belgian beer. This was not your all-night-samba sort of fiesta. Most of the participants stayed comatose throughout, slumped against the sides of the hut, and the average age was late forties. Many of the younger men had headed off from the villages to try to get work in Cuzco or at the hydro-electric station. Loosened up by a few glasses of chicha, I started chatting to a lively group of older women and one of them, Tía Ollas, invited some of us to stay up the valley near a little hamlet called Rayanpata. This seemed a good base from which to climb to a rarely visited pre-Inca site above on the cliffs, called Unuyoc.

The hamlet was at 10,000 feet, with a mountainside of forest rising up into the clouds behind. We camped near Tía’s hut and immediately started to receive generous amounts of hospitality. Tia gestured at some of her guinea-pigs. ‘When you leave, we will kill some for you,’ she said with a magnanimous if distressing gesture at the little furry creatures around her feet.

The hamlet was tiny. Social life revolved around the watering-hole where the women met in the evening to gossip and by day to weave large peppermint-coloured shawls they could sell down at Cuzco or Chincheros. Within a few days we got to know them all. Indeed, we spent a while at Rayanpata, lulled by their remarkably attractive lifestyle, which included getting good coffee sent up to them from Quillabamba in the jungle. Roddy and I had endless cups as we played backgammon and waited for the clouds to lift.

With us was a young archaeologist called Harvey Lilley, who impressed me by carrying War and Peace in his pack. After a week at Rayanpata he had almost finished it, as the mountains were usually covered by mist and drizzle and we could rarely climb them.

When we did get up to Unuyoc, we found it to be again on the end of a ridge, with the characteristic double-bonded circles and spectacular views we were getting used to. We started the job of measuring the site. Whatever the archaeologists might say, it seemed to me that all this called for was the ability to hold a tape-measure and draw an accurate diagram. Bingham had self-deprecatingly described his own initiation into this black art: ‘Fortunately I had with me that extremely useful handbook Hints to Travellers, published by the Royal Geographical Society. In one of the chapters I found out what should be done when one is confronted by a prehistoric site – take careful measurements and plenty of photographs and describe as accurately as possible all finds. On account of the rain our photos were not very accurate.’

It was early morning and my reactions were slow when Roddy told me there was a bear behind me. It took a while to realise he was joking and then another delay before I realised he wasn’t. The bear seemed surprisingly small, like Yogi Bear in the cartoon, and was looking at us with total bewilderment, having wandered up the side of the hill about fifteen feet away. He had dark circles under his eyes which I later learnt are the distinguishing feature of the Peruvian spectacled bear. My surprise was all the greater because, despite Paddington, I had forgotten that there were bears in Peru at all.

The bear blundered away, doubtless surprised at finding us. Pre-Incaic sites are rarely visited, lacking the glamour of the full Inca fortresses. The remains of Unuyoc’s walls were thinner than, say, Llactapata and the stonework less impressive. Yet such sites were a useful reminder of the precursors of the Incas. The Inca Empire had grown up rapidly on the back of countless others, many of which, like the Etruscans in Roman Europe, had been subsequently subsumed into their own history and architecture.

By the end of the day the clouds had set in again and we came down through the forests with the damp slowly rising in our nylon waterproofs. We told Tía about the bear and were alarmed to see one of her neighbours, Lucho, immediately head off with a battered shotgun.

Tía Ollas invited us in for a trago of rum on the Peruvian National day of Independence. We got talking about the land reforms that the village had seen over the previous decade. For centuries after the Spanish Conquest there had been a system in which certain landowners, the hacendados, had feudal rights over large estates, which they often abused. In the late 1960s the government had begun a limited process of land reform which had seen some of the more unpopular hacendados either got rid of or paid off by the government. The whole valley of Santa Teresa was now being run on a co-operative basis by an elected president, although Tia commented sharply that if this didn’t work they’d just get the old hacendado back. But she felt they had a much better standard of living than they’d had before.

In their valley, the campaign to get rid of the local hacendado, a man called Ortiz, had been led by the schoolmaster, who had persuaded the various villages to rise up and throw him out of town.

Tía Ollas had a radio in her hut and could tune in to local messages from Quillabamba. It was on while we were talking and when they played the national anthem, the villagers solemnly stood up and the men placed their hats over their chests. This did not seem like fertile territory for the guerrillas of the Sendero Luminoso.

Lucho returned from his search disconsolate at not finding the bear. Despite being relieved at his failure, I gave him a tin of peaches to cheer him up. When I wandered down to wash the porridge bowl the next morning, Lucho greeted me at the watering-hole with a cup of precious fresh milk, in silence. After weeks of nothing but tinned Carnation, it tasted like mother’s milk.

I had a pocket Shakespeare, and some lines from Hamlet stuck in my mind that night as I watched the moon rise over the mountains and the low mists hanging over the roofs of the village huts:

Hamlet: ‘But this is wondrous strange.’

Horatio: ‘And therefore as a stranger give it welcome.’

*

We left Rayanpata reluctantly. Indeed, Roddy and I were so sorry to depart that the others went on ahead while we ate a last meal of roast guinea pig with our various benefactors (the skin had a not unpleasant crisp quality, like chicken). It was already late in the afternoon by the time we got off. With the over-confidence of increased familiarity in the mountains (and too much beer), we decided to look for the abandoned Santa Helena silver mines on the way back. We soon lost our way and had a reminder of how quickly conditions could change at this altitude. The cumuli whipped in from the jungles to the east and, as it started to get both dark and windy, we could only just make out the proper path below us, separated by a steep drop over rocks.

We tried to scramble down and quickly realised that this was a bad idea. The scree of the rocks started to give way in the half-light, and we took off our heavy-framed backpacks as the forks kept catching whenever we slid down. Roddy was ahead to one side when I stumbled and fell awkwardly against a boulder, momentarily winding myself. My backpack took on a life of its own and lurched away from me, carrying on to fall some hundred feet down the slope, bouncing against the rocks, with a sound of crunched metal each time the tin pots that were strapped to it crashed against the stone.

In the half-light Roddy couldn’t see if I was still attached and started to shout for me. It took a moment before I could get my breath back and reassure him. We found a dried-up stream-bed and managed to pick our way down to the pack, which had unbuckled as it fell and had distributed various of my possessions over the mountain. The orange sleeping bag had burst open like a split body. Disconcertingly, there was an odd buzzing coming from the pack like a rescue helicopter – my little electric razor had switched itself on in the fall.

Battered, we struggled on to the camp at Colcapampa, picking out the path with our head-torches. Worse was to come. In Roddy’s own struggles down the rock-face, the tent-frame had fallen off the back of his pack and so we had no way of putting the tent up. Others took us in and I was soothed to sleep by Vaughan as he told me of the various insects he had spotted in my absence.

It was time to leave the main party and strike out on our own for Choquequirao. J.B. had done some more masterly negotiations while waiting for us and we had as many rations as we could manage, although limited by having only two arrieros (muleteers) to help us carry them. There was an experienced local guide in the village called Washington Delgado, a man with charismatic eyes and the owner of various pack animals. He decided to send his young son Willie with us, as a blooding for him, and another muleteer called Claudio.

Willie was an extremely self-assured eighteen-year-old. He brought with him his father’s white horse (it was never clear if we were entitled to ride the horse as well, even though we were certainly paying for it) and an instinctive feel for the difficult terrain we were going to travel through, despite never having been there before.

When the Comte de Sartiges had first made this journey in 1834, he and his men were forced to burn the brushwood ahead of them in order to make their way through what he described as ‘some of the most magnificent scenery in the Americas, but a path that was dètestable’. The rock was worn away in many places and destroyed by landslides while ‘the water which filters up through the granite makes the steps of the mountainous ascents shine like ice’. Sartiges built rope bridges to cross the chasms, and suffered the attentions of mosquitoes: ‘I do not believe that man could ever live in this valley, however fertile it is, because of the voracious mosquitoes that have taken possession of it. It was impossible to breathe, drink or eat without absorbing large quantities of these insufferable creatures.’ One of his men went over a cliff with a mule. The team drank rum morning and night to keep out the cold.

We were under no illusion about the hardships of the twelve-day journey that lay ahead of us. A perpetual disappointment for the explorer is that jungle paths, once cut, quickly revert back to shrub for the next expedition, and we knew that few had ever come this way since the Count.

But we were also as fit as we were ever going to be and were diet-hardened to the porridge, potatoes and tinned tuna that was probably all we were going to eat over the next fortnight. The luxuries of the Army compo packs had long since been truffle-hunted.

Then I made a chance discovery. The little shack in Colcapampa sold the usual array of subsistence goods that we had been surviving on for weeks. However, something caught my eye, high up on a shelf above the cans of Peruvian tuna fish.

Before we had set off on our expedition we had, as most explorers do, looked for sponsorship. Tate & Lyle had unexpectedly donated us a full crate of their Golden Syrup. As the excess baggage on this alone would have been enough to swallow half our available budget, we had sold it ‘off a lorry’ to a local catering concern near the North End Road and forgotten all about it.

But here on the top shelf was the unmistakable green-and-gold label of Mr Tate and Mr Lyle, on a tin covered in dust and chicken feathers. The Señora brought it down for me. The seal was broken and the top had been opened, with about a spoonful of syrup taken out, but to all intents and purposes it was a full tin. Apparently a previous expedition had left it there many years before as a barter for potatoes and eggs, and the locals had decided, after one tasting, that they’d made a poor deal.

We tried to conceal our eagerness as we bargained for it ourselves. It quickly became the high point of each day, something to look forward to as we hacked at the undergrowth and plodded along behind the flatulent mules, while our proper supplies of food inexorably ran out and the packs became perversely heavier: the moment when we could each measure out a spoonful of the syrup onto a digestive biscuit, watched carefully by the others, and lie back on the grass to enjoy every honey-soaked crumb.

The first few days were relatively easy. We climbed high up towards the Yanama pass and I sympathised with Willie on discovering that he too was experiencing bad toothache (although mine was finally abating). I bought eggs and an arroba of potatoes at the last small-holding near Totora.

We camped just beneath the Yanama pass and struck off early the next day to get over it before the heat came up. It was, to use J.B.’s phrase, ‘a bugger of a pass’ which seemed to recede further every time you came over a lip towards it. My altimeter had broken in the backpack’s fall, so I no longer had a reliable way of knowing quite how well we were doing. But finally we were through to the wild country on the other side (a previous expedition the year before had been beaten back by snow at the top, so we were lucky).

A succession of almost magical days followed. Every night Claudio lit deft fires in the most unpromising of locations and we would reflect on our progress. As Willie had never been to Choquequirao before, he was, like us, guessing at the precise route.

Initially it was easy, for our path lay along a proper Inca-laid road, bringing us down in some style through wild country to a long, shallow valley, irradiated by distant splashes of waterfalls against the green. We saw some curious blue eggs lying in clumps out on the rocks, in the open, as if there were no natural predators for them.

In the first flush of victualling our own journey, we had fine meals of tinned meat and potatoes, or pasta and beans, all surprisingly good for one-pot cooking. The only culinary dispute that began to develop was over porridge. Roddy liked his thin and milky, I liked mine thick and J.B. didn’t mind either way as long as it came fast. In the bitter cold of the Andean mornings after sleeping in our cramped tent, this was, as the counsellors say, ground for conflict.

At the small settlement of Yanama we again slept on a football pitch, this time belonging to the school. A quiet girl appeared out of nowhere, bearing potatoes, and we discovered from chatting to the locals that there was another back route from here towards Huancacalle and Vitcos, along narrow mule-tracks and over a high pass. Vitcos was the remote location of Chuquipalta, ‘The White Rock’, and of Manco Inca’s death, a place that intrigued me increasingly as I heard more about it.

Less encouragingly, the locals thought the route over to Choquequirao was impassable in places. We climbed on anyway up towards the next ridge, making our way with considerable difficulty, and after several false detours came to some old mine-workings set into a path along the cliff-face – a path that would have looked like a picturesque set from The Treasure of the Sierra Madre if we had not had to walk along it. The path crumbled away in sheer drops at several places, and Willie and Claudio blindfolded the horse and mule to lead them across.

When we came over the next pass, the San Juan, we could see the Apurimac itself, often described as the most magnificent river in the Americas. The name Apurimac means ‘the Great Roarer’, and this was one of its most impressive stretches as it cut savagely indented canyons in great serpentine arcs through the mountains. With its beginnings deep in the Andes, the Apurimac was thought to be the furthermost source of the Amazon. There were condors close over the pass, one a young bird with the lack of white plumage that showed it to be still undeveloped. The fringed wings of the condors looked gaudy, like the tassels on a moccasin jacket, and they had surprisingly stubby bodies between the huge gossamer expanses. The great birds were catching the thermals up from the valley and doing so in such an elegant way that it was easy to forget that they were essentially glorified vultures, feeding on carrion.

On the other side of the pass there were more mine-workings and some of these seemed to be still operational. Even though there were some hours of light left, we decided to stop early and camp near one of the shafts where there was a useful source of water, as there might be none below. This gave us the chance to have a leisurely fry-up of potatoes. By now we were ready to write the cookbook on 101 things to do with a Peruvian potato and had learnt to identify the six principal different types, from the floury and disintegrating hariñoso to the bullet-hard ones that came from the higher ground. The most unusual and, arguably, inedible were the freeze-dried potatoes, the moraya, which sustained Andeans through the lean months and which bore the same relationship to their parent potato as the raisin to the grape. Roddy tried to soak his in alcohol to improve the flavour, but they would have defeated an Elizabeth David.

That night we had a full moonrise, the moon lighting up little clouds like powder-snow before it took off from the ridge above us.

A man appeared at the camp-fire and introduced himself as the superintendent of the last lead and silver mine that was still working. We shared some whisky with him. He complained a lot about the local Quechua cooperatives, saying that they had no commercial initiative and only provided for themselves. It was certainly true that the locals didn’t have a grain of greed or commercial instinct about them, in a way that I found very attractive: they gave us food without a second thought, and we had to force gifts back on them. It was equally noticeable how avidly the superintendent stuck into our own precious supplies of whisky.

Roddy came up with a delightfully daft hypothesis to explain why the names of all mining communities (Yukon, Yellowhead and now Yanama) begin with a ‘Y’ – that this might be because they would then come last in the dictionary and throw any other prospectors off the scent. At 10,000 feet and after a couple of whiskies, the theory made perfect sense, and when we explained it to the superintendent he nodded in approval.

When I came back this way many years later, I found the mines abandoned and an ore-cart hurled over the side of the mountain onto the slopes below. The Sendero Luminoso had passed through and closed them down in their usual brutal and total fashion.

On our descent the next day we found to our surprise that the path was really superb, a full Inca path that had been maintained by the miners and descended in tough but disciplined gradients. The Incas did seem capable of miraculous stretches of engineering when it came to mountains. The only other time I’d been so surprised by man’s achievements at such altitudes was when travelling on the spectacular curved bridges and roads of the Italian Alps.

A full train of mules passed us as they made their way up to the mine. We had heard their bells tinkling from the depths of the valley long before we had seen them. It was the continued use of the mine which, in a gratifying way, had kept much more of the track open than we had expected, for even below the laid causeway the undergrowth had been trampled by the mules. But our way diverged. From here on the route became harder, and we had to get the machetes out, just as the clouds came up from the valley and enveloped us.

Once out of the cloud, we came to some of the most fabulous landscape we’d seen so far: rich purple flowers against the green of the selva, thick peppermint-striped red-and-white bamboo (one of which I cut to use as a switch on the mule), a huge flamboyant red orchid that the trees wore like a carnation, umbrella ferns, tiny shamrock-like flowers. Across a nameless small river, a tributary of the Apurimac, we saw our next day’s journey, a stark ascent up a fierce ridge.

The country on this side of the great Apurimac/Urubamba watershed was even more savagely indented by canyons than the terrain on the other side. Coming down, we wandered through neck-high grass-reed that by annihilating our vision to a green shade made the whole trip seem even more dreamlike than normal, particularly when Willie led us to a campsite that Jules Verne or Kipling would have enjoyed. With an enjoyable flourish, he slipped through a fissure in a seemingly impregnable ring of granite wall that emerged onto a small, perfectly formed plateau for camping, set near the river.

We forced ourselves to bathe in the water. The river was fast and freezing, and immersing the body totally under the tumbling glacial melt-water was like getting into a washing machine. I felt the way surfers do after battling a cold winter swell when they talk of ‘an ice-cream head’.

J.B. had been grandly designated in the promotional literature for our expedition as ‘Medical Officer’, despite his complete lack of any qualifications to be so (although he assured us that he had been on a first-aid course at school). However, it looked good – indeed, was probably essential – to have a Medical Officer on the letterhead, and J.B. looked the part; he even wore a striped shirt in the middle of the Andes. He also exuded a pragmatic confidence and a list-making ability that gave Roddy and me absolute confidence in his GP’s bedside manner.

How wrong we were only unfolded as the trip to Choquequirao got tougher day by day. The Medical Officer’s resources became increasingly strained. First we discovered that he’d forgotten the antihistamine. On a trip that took us on an etymologist’s tour of the underbelly of insect life, this was a bit like not bothering to bring any water, and Roddy and I put it to him, sternly, that he should at least forfeit a few days’ ration of our Tate and Lyle Golden Syrup as penance. Roddy’s machine that imitated the whine of a male mosquito had thankfully run out of batteries. We were already scratching like monkeys.

But worse was to come. That night J.B. was cooking and decided to test the temperature of the soup with his medical thermometer. Roddy and I watched impassively with the feeling that he must know what he was doing even if we didn’t. The thermometer broke and the mercury swirled around our few potatoes and tinned tomatoes. ‘Do you have a spare?’ asked Roddy in an Eeyore-like voice which presumed, correctly, that he didn’t. ‘Ah well, I suppose if we get ill we’ll know about it anyway. Antibiotics all round, eh?’

‘Actually,’ said J.B., a little diffidently by his usual cheerful standards, ‘I didn’t bother to bring the antibiotics. Big glass bottle, weighed far too much. It’s at camp. Left the Lomotil behind too. And the bandages.’

‘Jesus Christ,’ said Roddy with a heart-felt kick at the embers still glowing under our mercury-poisoned soup. ‘We’re in the middle of nowhere, at least a week from the nearest railhead, on a path that no one’s travelled for hundreds of years – and you’ve left the antibiotics behind. What precisely are we going to do if we get ghardia or the shits? Did you by any chance,’ and he paused to give his words maximum weight, ‘bring any form of medical supplies at all?’

‘Oh yes, there’s plenty of aspirin,’ said J.B. ‘It’s probably better,’ he continued with breath-taking assurance, ‘just to let any illness flush through the system anyway.’

That night we retired to bed early.

*

Claudio’s cry of ‘¡Mula! ¡Mula!, ¡Carajo!’ echoed up the hill as we struggled on the next morning. This was the worst section of the journey by far, virtually unpassable in places, and we often had to double back on our tracks. The canyon trapped the heat and all of us were drenched in sweat by late morning.

Claudio had told us that snakes usually bite the second walker in a group (on the grounds that while they might get irritated by the first passer-by, it’s the second one that really makes them lose their patience), and this naturally caused a certain amount of jockeying for position as we cut through the undergrowth.

When we did come across a snake, we heard it long before it heard us. There was an unholy sound of hissing and thrashing undergrowth ahead and we rounded a turn in the path to see a skunk locked in mortal combat with a coral snake. Claudio killed both with his machete and the skunk’s dying blast against the world stayed with me for the rest of the day, despite all the fragrant flowers we passed. I realised what the medieval writers had meant when they talked of the smell of sulphur in hell.

About one and a half hours up from the river, we found a ruin set back from the path, a site loosely called Espa Unuyoc by someone in Yanama on our return. This was not a site that the Comte de Sartiges had come across and we were not expecting it. There were at least six or seven layers of terraces, with many more stretching into the dense undergrowth, an irrigation canal and one particularly fine room which we set out to clear, with well-preserved doorways and recessed niches (Bingham liked to speculate whenever he saw a recessed niche that it must have been for mummies). We were excited by this and started to measure the site, discovering some intriguing features: a drinking fountain and also a little stone run-off to the actual canal which seemed to be designed as a drinking trough and could presumably have been stoppered and un-stoppered at will.

Because previous twentieth-century expeditions had always approached Choquequirao from the other side, across the Apurimac, no one had recorded this site and (although unaware of this at the time) we were the first to do so. Subsequent years well illustrated the problems that attend such Division B locations: no less than three later expeditions thought that they had discovered, or described, the same site first (the choice of verb is important and can reveal much about an expedition – while explorers will talk of an ‘undiscovered’ site, archaeologists like to talk of an ‘undescribed’ site). We were followed by a team of Cuzco explorers in 1985 – the so-called ‘Cuzco Ramblers’, whose genteel name belied their toughness and achievements – then by the American explorer Gary Ziegler in 1994 and finally by another expedition led by the architect Vincent Lee in 1995 – all of whom thought they were the first to find Espa Unuyoc (later renamed Pincha Unuyoc). Likewise, there may have been people before us who had passed through but had left no record.

There were some oddities in the masonry that we immediately noticed as being atypical – particularly the vertical stacking of stones near the principal gate, which was at odds with normal Inca practice.

After measuring the site, we climbed higher up and looked back to see clouds of smoke rising from the scrub above our camping-place by the river. We suspected Willie and Claudio, as they had lit a second fire after us. The fire seemed to be spreading across a substantial section of the slope, although contained by the walls of the river plateau. We watched gloomily. I thought of Donne’s lines, ‘And that this place may thoroughly be thought / True Paradise, I have the serpent brought.’ We ate the last chocolate with our biscuits at lunch and tried to keep away the flies.

As if to punish us, the next section was very tough indeed. A hard slog up was followed by a vertiginous path skirting above the Apurimac: the river canyon was sometimes hidden by the dense undergrowth, but we could always hear it swirling thickly below. The vegetation changed with bewildering rapidity as we moved from wheat-coloured grass into a dense woody section that could have been a forgotten corner of England, with wood pigeons – cuculas, as Claudio called them – crashing out of the trees at our approach.

There was a lot of pushing through the undergrowth as we tried to hack a way for the pack-animals. Considerable damage was done to the baggage when the mule ran into low branches. My jacket got ripped by some vicious brambles. The problem with using machetes was that we were constantly at risk of cutting ourselves when undergrowth gave way unexpectedly and we got tired.

When we first saw Choquequirao, it was bathed in sunlight on its ridge, looking literally like a ‘cradle of gold’, its meaning in Quechua. It was late and there was no time to reach the ruins themselves, but as I gazed across at them a brilliant red-and-green woodpecker came into focus in the foreground, as if the lens had been pulled. A sheet of green went over us and for once we could properly see the parakeets we had heard so constantly above the trees or glimpsed in silhouette at a distance, flying against the sun or cloud.

That night was clear enough to view the Southern Cross again and we had a triumphant swig of Remy Martin to celebrate our coming.

*

One of the best things about arriving at the ruins was that we could finally sleep in late after days of early cold starts. By the time we wandered over to the site of Choquequirao itself, we were in holiday mood. To get there, we followed an endlessly long wall above which we could make out long terraces and the occasional stairway plunging up into the undergrowth – although some of the stairways had been blocked, for reasons I was to discover much later. The quality of the wall and the monumental size of the terraces indicated a major settlement. Choquequirao was often described as a ‘sister-site’ to Machu Picchu.

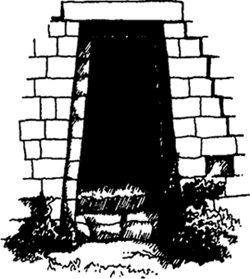

We came to the most visible set of ruins (it looked like there were many more below in the jungle): a long kallanka or meeting-hall dominating the side of a plaza, several more beyond and a great trapezoidal doorway leading through to what may have been a sacred enclosure on top of the ridge. It was satisfying to see perfect and well-preserved examples of the architecture that we had previously come across in a much more dilapidated state, even if much of it was still covered by the undergrowth.

Bestriding the mountain saddle, the city centre had a dramatic view down towards the Apurimac thousands of feet below, moving like a grey ribbon through the green as it began its long journey to join the distant Amazon. It was a most extraordinarily isolated site, and while theoretically useful as a look-out post for attacks from the north, it did not appear to have heavily fortified defences.

A large group of gabled buildings had prompted the Comte de Sartiges to think of Egyptian styles when he came here, and there was an ornateness that I had not previously associated with Inca architecture – a profusion of double-recessed doorways, for instance. However, it was not the buildings that intrigued me most about Choquequirao. Rather, it brought home to me a feeling that had been building up over the course of our explorations.

My impression, from having seen some of the hidden sites of the area, was that the Incas in the sixteenth century were a culture unusually obsessed with the beauty of mountains, in a way that European culture would only assimilate hundreds of years later. Why else build Choquequirao – and Machu Picchu itself, another site draped over the fold of a mountain – far from any convenient source of water and with only their superb views to recommend them? Why did they fetishise mountain rock, elaborately carving into it to draw attention to the natural landscape on either side? Why do the Incas’ accounts of their origins go out of their way to attest to a symbolic birth in the mountains, rather than in the lakes and gardens of almost every other ancient culture’s mythology, both Mesoamerican and Caucasian?

Yet the way in which the Inca sites were located to maximise the mountain setting (‘view’ seems too tame a word) had been virtually ignored as incidental by those seeking to explain such sites. Archaeologists and explorers may have failed to appreciate the primacy that the Incas gave to mountain aesthetics, for a number of complex reasons.

One was to do with the history of our own appreciation of such landscape, acquired long after the Spanish Conquest of Peru. In the sixteenth century, when Pizarro arrived, Europeans still regarded mountain landscapes as savage wilderness and the Inca attitude towards them would certainly not have been understood. Given that almost all our primary sources for what we know of the Incas are filtered through contemporary European sensibilities (including that of the Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, who wrote a classic account of his ancestors after many years of living in Europe, and seasoned it to please a Spanish palate), there was no reason for an Inca cult of the mountain to be either noted or understood.

Only in the late eighteenth century, with Burke and his theory of the sublime, Wordsworth and his mountains, Rousseau and his thoughts on Nature, did any sense of the romantic appeal of such wilderness areas begin in Europe. But having discovered such a sensibility ourselves, there has always been a reluctance to ascribe it to any other culture, let alone one which might have come to it before us. This and an equal reluctance by the modern anthropological and archaeological disciplines to allow any explanation of different cultures other than a strictly functional or religious one seem to have been powerful impediments to a clear assessment of the Inca sensibility.

It seemed an odd vestige of cultural patronage, as blinkered as the original missionaries who could not recognise the validity of any religious convictions they had not themselves arrived at. Why should we be privileged to appreciate a mountain setting and assume that the Incas could not? Why should the buildings have strictly functional or religious purposes, any more than all buildings in Europe did? From the comparatively little we know of the Incas, theirs seems to have been a culture which worked precisely by not being strictly functional.

We went further down the ridge with Claudio, where we found a small two-roomed building with an outer rampart. Roddy, with his neophyte enthusiasm for Inca architecture, pointed out that the features of the building were neither classic Inca nor for that matter particularly distinguished, but it further confirmed my thoughts, as it had the finest position of almost any building I’d seen in any set of mountains, with a magnificent view down both sides of the ridge to the river.

Roddy and I walked on down the ridge as it became a razor’s edge and perched successively on the most eyrie-like position of all as we took photos. It was like sitting in a crow’s nest: the river seemed to run right around the vertical pinnacle of the rock we were sitting on.

I felt completely cleansed, a marvellous pure mountain feeling, in the middle of nowhere with only the euphonious river twisting its course thousands of feet below. I noted in my diary ‘a feeling of rare and elusive empathy with the Incas, mountain people who pick the most spectacular and difficult of refuges’.

Perhaps the ideal explorers to the area would have been Wordsworth and Coleridge. If Coleridge’s scheme for a Pantisocratic society in North America had been transplanted into a similar scheme for Peru (hardly less fanciful), would we have a ‘Lines written above Choquequirao’ which, like Wordsworth’s poem on Tintern Abbey, managed to ignore the buildings completely and just concentrated on the setting, ‘these steep and lofty cliffs, / That on a wild secluded scene impress / Thoughts of more deep seclusion.’ Certainly it was the Romantic impulse that brought early nineteenth-century French explorers like the Comte de Sartiges and Léonce Angrand here, weaned on Humboldt’s stirring tales of the Americas and their infinite possibilities. Wordsworth’s lines about the ‘still, sad music of humanity’ echoed with me as I squatted high above the Apurimac by the lonely set of deserted buildings.

Señor Lucas Coborubias, the aged caretaker of the ruins, came up from his hut to talk to us when he saw the smoke from our fire. We signed his book, which showed a trickle of visitors over the years. Lucas spoke only Quechua, so Willie translated, and it emerged that Lucas had been at Choquequirao as a young boy when Hiram Bingham first arrived in 1909. Looking at his face, it was conceivably true. Little had been done at the site since Bingham’s visit and it had never been properly excavated.

There were many questions to ask about the place. Had the Spanish ever discovered it? Certainly there were no references to it in their literature. Roddy and I had found shards of pottery everywhere, littering the ground in places. Were the ceramics colonial? And was this one of the places that the Incas had retreated to after the Spanish invasion? It was remote enough to deter any pursuit. For the while I was happy enough to stay in a state of what Keats described as ‘negative capability’, absorbing questions without trying to give answers.

That evening we had a salad of dried peaches and apple soaked in rum, reckless in its extravagance given that we had so little food to make the return journey, as J.B. pointed out. He was the most cautious of us, a necessary counterfoil to Roddy and my sudden enthusiasms, and a natural quartermaster. J.B. amused us by husbanding the toilet paper he’d wrapped his lunch with, just in case he needed to use it later; when supplies of paper did indeed run low, he had the last laugh.

Roddy spent hours trying to coax his potatoes into gourmet perfection over a spitting and smoking fire, much to Willy and Claudio’s entertainment. They were relieved to have got here with so little rain, as this section of the Apurimac was notoriously wet even in the dry season. That night I woke to the sound of a heavy downpour and, remembering that we’d left the food out, screamed at everyone to help me cover it with the tarpaulin and the mule’s blanket.

They say that for mountaineers going down is always tougher than the ascent, and certainly our own journey back felt harder, now that we no longer had the testosterone charge of getting to Choquequirao.

Conversationally, we had by now speculated about the love-lives of almost all those we had ever known, of many that we hadn’t and certainly of all those back at the Cusichaca base-camp. We had wondered avariciously about the high starting salaries given to some graduates we knew who had become bankers, and were doubtless having three-course lunches at shareholders’ expense in the City while we ate boiled potatoes. For one particularly strenuous climb, Roddy and I played a game in which we constructed the perfect wine cellar, giving ourselves generous sums to do so: he speculated in vintage claret, I in burgundies. When Roddy moved on to the comparative advantage of white madeira over port, as the butterflies swirled around and the air chattered with the intensity of a mountain forest, I began to feel I was hallucinating. Meanwhile the boiled water flavoured with Stereotabs went tepid in our water-bottles. Once all conversational diversions had been exhausted, there was nothing to think about but the unremitting load of the packs, the thorn-bushes whipping back into our faces and the endless farting of the mules.

When we camped again at the site by the river where the fire had been, the scorch marks traced back with sickening accuracy to our fire, not Willie’s, as he was quick to point out. However, the damage to the surrounding vegetation was less severe than we had feared and I went for a swim in the icy water of the river for absolution.

Willie and Claudio worried that supplies were getting low. As morale plummeted, I got out the last ‘luxury pack’ I had brought from England – a small tin of truffle pâté which had sounded exotic when I had bought it but was now both dull and insubstantial. We had long since finished the Tate & Lyle Golden Syrup. My diary entry for one day’s journey was terse: ‘The food has become monotonous, we already know the route and the weather is bad.’ The constant rain had started to soak through our grimy underwear.

By the time we arrived back at Yanama in the mist, the urge to explore had begun to fall away from us. We had said to David that we would make a detour to look for a possible pre-Inca site he had heard of above the schoolhouse, and we had left this for the return journey. Now our good intentions started to fade, particularly as, after a scramble up, there seemed to be nothing but an endless succession of sprawling cattle-pens. I felt my team slipping away as we discussed the merits of continuing to look.

David himself had been unable to get across the pass the previous year because of snow and I argued that we should at least try to do this for him, now that we were here. In the end I suggested the one lesson in leadership I had learnt so far – that we stop for lunch. The cold potatoes and our last tin of sardines didn’t get us far after a hard morning’s walk, but in the meantime Roddy, who had gone to eat by himself and sulk, discovered the pre-Inca site just ten feet below us in the mist. Our earlier mistake was slightly less stupid than might appear, as the site consisted of the simple, low, double-bonded rings we had seen at Unuyoc and, as such, was easy to miss among the cattle walls. We became enthused again and shot off a roll of black-and-white film for David.

Willie and I then toured the Yanama huts trying to barter for potatoes and the odd egg. We were a good double act, as Willie’s local connections could play off my novelty value, but we were sent ever higher up the valley by the stone-walling inhabitants. ‘Manan kanchu, there isn’t any’, was the constant Quechuan refrain. Normally I admired the way the Peruvian Indians would only sell a fraction of what they could – the reticence was appealing. But not now. The superintendent at the Vittoria mine had told us that the Yanama population were dificil, but this became infuriating. ‘Esa gente son muy cerrados,’ said Willie, ‘very “closed” people,’ and I could not but agree. Even the local shop had nothing for us.

To make matters worse, one of the mules bolted, at least having the sense to go the right way up the valley, and Claudio disappeared after it. It took us a while to catch up with them. When we did, there was one of those little oases of surprise that Peru sometimes brings. The very last house in the valley, a small one, offered us not only potatoes, eggs and coffee, but some chicharrones, hunks of pork ribs. Apart from the odd tinned frankfurter, this was the first meat we’d had in weeks (indeed, since those memorable guinea pigs) and we fell on it with rapacity.

The image of that final night is imprinted on my memory: a strong fire guttering up out of the elaborate stone hearth that Claudio had been teaching me, with much comment on my slowness, to make at each campsite, clouds over the mountains to the north, drinking all of our whisky (as Willie pointed out, there was no point in returning with any) and endless mugs of sweet tea – finally going to bed drunk and happy in the knowledge that there would be an extra egg for breakfast the next day.

*

David was leaning against the doorway of Washington’s house at Colcapampa when we returned, looking even more like a Hollywood leading man than usual and swigging on a bottle of beer. ‘Buenos Días, Señor Hugo,’ he said with a deadpan expression. Ann Kendall was also there – she had come over from Cusichaca to see what progress had been made. A slight flicker of a smile showed that she thought the expedition had gone well.

The hot waters were a life-transforming moment. After the two-week-long expedition to Choquequirao and back it was hard to get my trousers off, let alone washed. The tough corduroy material had been ripped to pieces by thorns and rocks. I sat in my underpants, in the sun, eating fried-egg sandwiches and having as much hot coffee as I wanted. It was a wonderful feeling. Even the tins of Gloria condensed milk now looked appetising: how could I ever have looked at them with such indifference?

I had an awkward parting from Willie, whom I’d come to like over the journey, and I gave him all we could afford as an extra tip over the agreed amount. Then he asked for my watch as well. It was a Graham Greene moment, in which I felt all the anxieties of inequality, ultimately resolved by the fact that I needed the watch too much to give it away. This did not stop me from feeling guilty, or Willie from feeling aggrieved.

Striding back down the Santa Teresa valley, my pack felt light with the relief of having come through it all so well, and when I arrived at Miscabamba, where I had previously suffered the anguishes of a wisdom tooth, it seemed a different place. The one book I had taken to Choquequirao was a paperback of Robert Byron’s The Road to Oxiana and I’d been struck by the pleasure he took in revisiting places: that often what was most interesting was not one’s initial impression of a site but the contrast between that first impression and one’s later growing understanding of it.

I thought of this as I passed Suriray the next day, our leaping-off point for Llactapata. Those ruins, with their surprising hidden sight-line of Machu Picchu, made more sense now that I’d seen Choquequirao. What the Incas seemed to enjoy was not just a view, but a revelatory view.

J.B. and I struck off from the others to investigate a strange report from a man called Andrés who was based near Miscabamba. He told us of a burial cave above the valley and when we got there, at a site called Larmapata, we did indeed find a shallow recess filled with human and animal bones. J.B. and I gingerly cleared a space to get down to work. It was an odd feeling to be sifting through the bones (skulls, a human foot, some vertebrae unstrung like a broken necklace across the cave floor) looking for the really important evidence – pieces of pot – which we were unable to find. The setting stayed with me, though, with the yellow-white bones on a ledge: ‘Those are pearls that were his eyes.’

Afterwards we had lunch with Andrés, our informant. He had a smallholding of about 50 hectares sufficiently below the crucial altitude of 8000 feet to enable him to be self-supporting in maize, potatoes, carrots and avocados – he only needed the market for sugar, salt and oil. Andrés was the first person I’d met to be superstitious about old sites, telling us calmly that we were likely to be blasted by thunder and bitten by snakes for our intrusion into the cave. To show that he didn’t hold this against us – indeed, he rather pitied us – he prepared a special dish of cuy (roast guinea pig).

By now we knew the procedure. First the children would round up the herd until they formed a circling wheel of fluff and fur in the middle of the hut. Then all faces would turn expectantly to us as, Caesar-like, we had to decree which should live and which should die. The decision made, execution was swift and the animals would be spitted over a roasting fire. It was enough to make you vegetarian for life, although the children accepted the ritual sacrifice of their pets with remarkable equanimity. Indeed, the guinea pig is a good example of the pragmatism at the heart of much Andean culture, in the way they serve not only as pets and useful vacuum cleaners around the floors of the huts, but ultimately as food.

Back at the Santa Teresa train station that night, we had to wait for the train which had been delayed downriver. As we sat in the sleazy café, with its Kenwood mixer in a glass case (Kenwood mixers were status symbols in the remote areas of Peru), drinking beer and listening to the rain and dogs outside, Ann Kendall started to talk at length. Up until then, I had hardly heard her utter two consecutive sentences, but the end-of-trip release and possibly the freedom of being away from her responsibilities at the main camp seemed to unburden her. For the next few hours she talked of the discoveries she was making, as outside the rain got worse and the dark set in.

Ann believed in the overriding importance of listening to local inhabitants when it came to investigating sites, an idea that might seem blindingly obvious but was often ignored. I have seen archaeologists jump out of their four-wheel drives, take detailed readings with compasses and altimeters, draw immaculately detailed site plans and then jump back into those same jeeps – without so much as a word to the people who live nearby.

She told a story about the famous rings at Moray, which lay not far upriver. A series of natural hollows in the mountains had been turned by the Incas and their predecessors into a stunning set of concentric terraces that disappeared into the earth below like some physical enactment of the circles of Dante’s Inferno. Their purpose had puzzled observers for centuries. Studies had suggested one possible reason – that the night-time temperature for each layer of terrace dropped significantly as you went down. This had given rise to a number of hypotheses, the most elaborate being that the Incas had used it as a ‘laboratory’ to develop different varieties of maize for the extremes of climate found within their empire. It was still a familiar sight outside Quechuan huts to see a pile of corn in a heap of many colours, from the familiar creamy yellow sort to varieties speckled with red and brown kernels, and the jet-black morada corn used in a speciality chicha drink.

Ann had a simpler suggestion, derived from a local woman who had looked at her as if she was stupid when she asked the question. ‘It’s for freeze-drying moraya potatoes, of course – that’s why it’s called Moray.’

A drunk swung by the café, lurching towards us and demanding money. We ignored him. Ann continued, her low, quiet voice holding our concentration.

A decade of working on sites along the Urubamba and doing so in a way that kept her inside the community had given her a down-to-earth view of Inca life, especially its secular side. She rejected romantic theories such as Bingham’s, who liked to describe Machu Picchu as a mysterious religious hideaway for the Virgins of the Sun.

Instead she described how Pachacuti Inca, the great initiator of Inca expansion out of their Cuzco base, had built the temple-fortress at Ollantaytambo when he had conquered this area, and how he and his successors had expanded their empire down the valley to build Machu Picchu. She speculated that rather than being a religious site, Machu Picchu, with its milder climate, would have made an ideal winter base for the Inca and his court, an attractive retreat from the cold of Cuzco. One of its purposes may also have been as a vast hunting lodge in what was an outstanding area for game – indeed, so outstanding that the area around Machu Picchu is now a protected sanctuary and has the unusual distinction of being a Unesco World Heritage site for both architecture and wildlife.

The idea of Machu Picchu and its surrounding area as a pleasure centre, built by either Pachacuti or his son Topa Inca, was a revelation to us, an idea that made sense of much of what we had seen, and particularly my feelings about the aesthetic supremacy of view and location.

Ann warmed to her theme, as we asked her about the significance of some of the paths we had taken. She speculated that the way the paths seemed to end abruptly on our first trek along the Mesada and Aobamba, which had so puzzled us, was completely consistent with a hunting path – once in the game area, there was no reason to proceed.

Patallacta, the site that Ann and her archaeologists were digging at Cusichaca, offered further evidence for this, as it seems to have been a service town for Machu Picchu, providing the city with crops which its own extraordinary position on top of a mountain made impossible to grow. Patallacta was not necessarily lived in by the Incas themselves but by client peoples, gastarbeiters, who may have been shipped in from another part of the Empire to do the job. The Incas, like Stalin and his treatment of the Cossacks, were fond of moving potentially difficult peoples to new, uninhabited areas.

We had to wait until midnight before the train arrived, so we hunkered down in sleeping bags on the platform, trying to ignore the fighting dogs and the sound of drunks bawling along to the tinny huayno music that was coming out of the radio. As the train then rattled up the valley through the tourist town of Aguas Calientes, where people stayed to visit Machu Picchu, the sleeping Indians hunched in ponchos along the carriages were lit up by the neon strobing from hotels and restaurants, and I reflected that in an odd way Machu Picchu had returned to its original function of resort town.