TO BOLIVIA AND COLLASUYO

I WAS NOW FOLLOWING in the path of the Spanish chronicler of the Conquest I most admired, Pedro de Cieza de León. He too had ridden out from Cuzco towards modern-day Bolivia in order to explore the further fringes of the Inca Empire. In 1549, a few decades after the Conquest, he had reached Lake Titicaca and the monumental ruins of Tiahuanaco nearby. He was the first European to leave an eyewitness account of them.

Cieza de León had been hooked on the idea of the Inca Empire since he was an impressionable thirteen-year-old living in Seville. In 1534 he had seen one of the first ships of booty brought back from Peru by Hernando Pizarro. When Cieza came to write his great Chronicle twenty years later, he recalled ‘the rich pieces of gold that I saw in Seville, brought from Cajamarca, where the treasure that Atahualpa promised the Spanish was collected’. The sight of the beautifully crafted Inca treasures must have been magnificent, particularly as it was such a transient one – the treasures were immediately melted down to feed the coffers of the Emperor Charles V for his endless European warfare.

Fired up by what he had seen, the young Cieza de León managed to secure a passage on a boat heading to the New World. However, it was not until 1547, by the time he was twenty-seven, that he finally arrived in Peru, as part of a Royal Army that had been sent to put down an insurrection of settlers led by another Pizarro brother, Gonzalo: the settlers were revolting at the so-called New Laws from Spain, designed to give the Indians more rights and prevent them from being treated like beasts of burden by their new owners.

During the intervening years Cieza had been blooded in campaigns in Colombia, had searched for a passage through to the Atlantic, narrowly avoided being killed by Indians using curare poison and had gone looking for El Dorado – in short, all the usual training grounds for a budding conquistador.

But Cieza differed from most of his contemporaries in one essential way – by the time he reached Peru he had got into the habit of taking copious notes of all that he saw. This was not a common characteristic among the ‘second generation’ of conquistadors who headed down to Peru after the first gold rush of Mexico had subsided. They were an altogether rougher and less educated group of men. While Cortés had been a skilled writer whose letters to the Emperor about the Conquest of Mexico are impressive literary documents, Francisco Pizarro could barely sign his name. (Perhaps as a consequence, Peru has always taken a surprisingly benevolent stance towards analfabetismo, illiteracy: there are still lesser legal penalties for those who ‘could not read, so knew not what they were doing’.)

Cieza’s great virtue as a chronicler was that he had no political or religious axe to grind, other than a mild, understandable aversion to Gonzalo Pizarro, and his account is fresh and forthright as a result – so much so that when it came to publication many years later, the Inquisition suppressed most of it. Lines like ‘for wherever the Spaniards have passed, conquering and destroying, it is as though a fire had gone, destroying everything in its path’ were not popular at a time when Spain was trying to live down the leyenda negra, ‘the black legend’ that was beginning to accumulate around its doings in South America.

The slow progress which the Royal Army made down the coast enabled Cieza to describe the Inca Empire in great detail. He wrote his account as a travel book in the true sense, in that it interwove reflections on Inca history and customs with a physical description of the country as he passed through it. I found it amazing that he had been able to preserve his increasingly bulky manuscript over the years, as he fought in battles and crossed and re-crossed the old Inca Empire (he was upset when he lost a few sheets in a climactic victory over Gonzalo Pizarro’s forces – he really did seem to carry the whole manuscript with him in a knapsack).

The point that he returned to again and again in his Chronicle was what brilliant administrators the Incas had been and how inferior the Spanish were by comparison. The Incaic road system, their communal labour projects and their ability to coax terraces and irrigated fields out of the toughest of conditions filled him with nothing but admiration. He was careful also to refute some of the more common slanders that were being used by the Spanish to justify the Conquest – for instance, that the Incas encouraged sodomy, which as Cieza pointed out, was far from the case: they actively persecuted other tribes, like the Chimú on the coast, for practising it.

He was impressed by the way in which the Incas had so often won over subject tribes without warfare. Their technique was first to send in spies. Then, after carefully weighing up the local situation, the Incas would let the old chiefs know that they could still keep their positions if they joined the Empire. Judicious bribery with concubines and textiles (cloth had enormous value in the Andes) further lubricated the transition.

Above all the Incas made it clear that they would win whatever happened, because they always did. Cieza reported one Inca Emperor as saying to a prospective new tribe, ‘These lands will soon be ours, like those we already possess.’ Given the Indians’ often fatalistic turn of mind, this proved effective diplomacy and many tribes gave in without a fight.

The Incas were adept at incorporating such new tribes into the Empire. Pachacuti had instigated a typically efficient method for achieving this. Local populations had always carried out works of communal labour, or mita, for their own infrastructure. Now large numbers of people were taken from their homelands to serve as tribute labour elsewhere, in a new system called mitamayo. The workers themselves were known as mitimaes. To take their place in their own community would come other workers from other tribes: ‘In this way all was quiet and the mitimaes feared the natives, and the natives feared the mitimaes and all occupied themselves only in serving and obeying.’ It was a system of divide and rule that appealed to Pachacuti – he seems also to have instigated the Inca practice of splitting towns into two halves, a lower and an upper sector called hurin and hanan, who would compete with each other in providing services to the State and to the town itself, like some glorified version of ‘house-teams’ in a school.

As part of the process of absorbing new peoples, the place-names of conquered towns would be changed to Quechua ones. And just as Pachacuti had effectively created a dynastic myth for his own succession, there is some evidence that the Incas also substantially retold the history of preceding civilisations to down-play their achievements, and in some cases to ignore them completely. Cieza reports, quoting his Inca sources, that before them there were only naked savages and that ‘these natives were stupid and brutish beyond belief. They say they were like animals, and that many ate human flesh, and others took their daughters and mothers to wife and committed other even graver sins.’

This manipulative distortion of history (common to other conquering pre-Columbian cultures like the Aztecs) was so successful – the same myth was repeated by other chroniclers like Garcilaso de la Vega in the early seventeenth century – that the truth has only emerged comparatively recently. Far from imposing order on an unruly bunch of savages, the Incas were merely the latest dominant tribe (and a short-lived one at that) in a series of Andean civilisations that had flourished over the preceding 2000 years: the Moche in the north of Peru, with their magnificent pottery, the Huari of the central states and the Tiahuanaco culture near Lake Titicaca (whose capital I was travelling to) were just a few of the cultures that had attained a high level and on whose achievements the Incas had often built.

It was a German archaeologist, Max Uhle, who first began to reveal how literally deep the roots of Andean culture were. In dig after dig in southern and central Peru in the early twentieth century, he showed conclusively that the Incas had been preceded by earlier cultures and that some of them had built up similarly far-flung empires. In the north, the doyen of all Peruvian archaeologists, Julio C. Tello, had in 1919 excavated the even more ancient culture of the extraordinary Chavin de Huantar, with its jungle iconography of snakes and jaguars dating back as early as 500 BC – two millennia before the arriviste Incas.

Cieza de León would have appreciated the conservationist change that was sweeping over Peru as a result of increased pride in this rich heritage. After centuries in which ancient tombs had been seen as a legitimate source of plunder – the early Spanish had even issued mining licences to prospectors to extract gold from them – they were being protected and restored. Cieza had deplored the way in which Sacsahuaman was vandalised by the Spanish conquistadors after the fall of the fortress-temple at the time of Manco Inca’s rebellion in 1536: ‘I hate to think of those who have governed in allowing so extraordinary a thing to have been destroyed and cast down, without giving thought to future times and events and how much better it would be to have it standing and cared for.’

His main complaint – which won him few friends, not least because it was grounded in truth – was that if you let illiterate conquistadors govern countries, you were going to get disastrous results. No wonder that he died embittered and dismayed in 1553, only a few years after returning from Peru, in the knowledge that while he had successfully published one book, the rest of his great manuscript would almost certainly be suppressed. He had given the better part of his life to the dream he had seen on the quayside of Seville, and when he died at just thirty-three (some said of a broken heart after the death of his beloved wife, or of a sickness he had picked up in Peru), it must have seemed as if for all of those years he had been chasing a chimera.

I liked to think of him, though, on that day when he first took the High Road south out from the Great Square of Cuzco towards Collasuyo, the Quarter of the South, with the knowledge that every writer craves – that he was going to be the first to report on all that he saw.

*

Above Cuzco, the upper Vilcanota river was viscous and sluggish as it meandered along the valley: it had carved great curved gorges that were monotonous in their regularity. As we got ever higher into the puna, the landscape became more barren, with plains of yellow and gold that looked as if they ought to be wheat but were in fact pampas grass.

I remembered Cieza’s words: ‘The excessive cold of this region is a handicap, and the grass that grows here is good only for the guanucos and vicuñas.’ We passed a section where there had recently been some burning and the whole valley was patterned yellow and black as if it had been kiln-fired.

Having been away in the mountains for months, it was a shock to be back on a tourist route. The railway between Cuzco and Puno was a funnel-neck for travellers from Peru to Bolivia and the city of La Paz, who then went on to Argentina and Brazil. For what was an enormous continent (the width of South America being greater than that of the Atlantic Ocean), there were surprisingly few transverse routes. As a result, a sort of ‘Gringo Trail’ had been established, helped by a guide-book of the same name, which had become self-fulfilling: many travellers never deviated from it.

There was a group of Spanish travellers in the carriage with me, complaining loudly about the Indians as ‘maleducados, badly brought up,’ and insisting that I moved my rucksack so that it was directly above my seat – very different from the easy-going behaviour of those same Indians on the mountain trains. That night in Puno, I dined on fresh-water trout from Lake Titicaca with an Australian girl and an American couple I met. The talk was all of muggings in Colombia, of hepatitis, dollar exchange rates, getting ripped off and of marathon journeys across half the continent. They couldn’t believe that I had spent so many months around Cuzco. ‘Cuzco is a five-nighter, maybe eight if you do the full Inca Trail – but no more,’ said the Australian girl in an authoritative tone. She was a big, full-breasted, athletic girl and looked like she would brook no argument.

Puno was generally considered a ‘one-nighter’, if that, but I wanted to hang around and in particular visit the ‘floating islands’ of Lake Titicaca, which had intrigued me ever since I was a child.

I went first to see the nearby ruins of Sillustani. I knew nothing about them other than a few lines in a local guide-book stating that they were there and Cieza de León’s description of ‘the tombs of the native chiefs of this place, as high as towers, broad and square, with doors towards the setting sun’.

What I saw, scattered over the hills above Lake Ayumara, was a host of stone monuments, standing upright against the skyline on otherwise barren ground: they were chullpas, burial chambers, some big enough to take a score of bodies and built with huge blocks in the style that originated around Lake Titicaca.

Sillustani was mainly the work of the Colla, one of the tribes whom the Incas had suppressed in their conquests here and after whom they had named this quarter of the Inca Empire (Collasuyo). Some of the outlying monuments were crude, smaller structures. But the four or so principal towers at the centre of the complex had a powerful if skeletal presence, with the shimmering lagoon behind: the magnificent desolation of the Altiplano stretched out ahead of them, like the desert around Ozymandias’ prostrate head.

However, as I got closer I realised that not all of these central towers were Colla, for they gave a fascinating example of how the Incas could sometimes directly copy the work of others.

One of the four, the largest, was indeed Colla, built with massive cubes of a warm ochre stone and similar to the many smaller monuments on neighbouring hills. Some of the cubes had spilled out from the coiled tower, revealing that they were hollowed on the sides, perhaps to allow adobe bonding between them. But the three other principal towers were clearly Inca, while modelled on that of the Colla. They had followed the same unusual shape (the towers widened as they ascended, in contravention of every architectural instinct), but used blocks of grey granite in the usual Incaic way, irregular but precisely fitting and with some of the strange projecting bosses which I had seen on other Inca buildings and which always caught my attention. They shared the same small plateau with the Colla tower, and overlooked the Ayumara lagoon. Were the Inca towers imitation as flattery or were they a boast by the conquerors – anything you can do we can do better?

The Incas certainly took the monumental style of building they found in Collasuyo back with them to Cuzco and assimilated it as their own. Because they suppressed so much of the history of the tribes they conquered, what little we know of such cultures – and what, therefore, the Incas borrowed from them – tends to come not from Inca records but from enquiries by the conquistadors. The Spanish didn’t conduct these out of anthropological curiosity but rather to prove that the Incas were unlawful rulers of conquered territory and could therefore themselves be legally usurped – a typical bit of pedantic legalism on their part.

The warm stone used on the towers glowed against the sombre backdrop of the Altiplano – a backdrop made more sombre by the build-up of storm-clouds behind, which unleashed not only rain but a dust wind of scratching ferocity, a wind that had me running for my taxi with my head huddled in a coat.

As I drove back into town, I passed a mortician’s with an advertising logo: ‘Funeraria – Servicio Permanente’ (‘Mortuary – Permanent Service’). Puno was not a cheerful place. Exposed to the Altiplano, it seemed to be forever raining – no wonder that most visitors, including the Incas, had always preferred the more secluded climate of Cuzco. To keep warm, I was forced to buy an alpaca jersey (something I had vowed always to resist), and even though I managed to find one that had no llama motifs and wasn’t cardado, ‘combed out’ to look like a moulting hamster, it still felt like a garment John Denver would wear to play songs by the fireside.

The wind lasted for days and turned the waters of Lake Titicaca sheet-metal grey. It was like Weston-super-Mare in the off-season.

*

The ‘floating islands’ of Uros did not live up to my expectations. ‘Floating’ is anyway an erroneous description (they are more properly ‘anchored’). The islanders were said to have originally fled from Spanish occupation and enforced work in the mines. They had constructed the islands out of reeds and now spent most of their time cutting new reeds to add to the surface as the islands continued to sink. This had acquired more urgency in the previous few years as changes in river-distribution from the surrounding Andes and the receding snow-line were causing the water-level to rise. Titicaca is a volatile lake and the changes in its levels may well have precipitated declines of civilisations like that of the Tiahuanaco.

Indeed there is a theory that many of the pre-Columbian civilisations (with some exceptions like the Chimú, who were conquered by the Inca) may have ebbed and fallen as a result of climatic changes rather than colonisation by another power. The occasional eruptions of el Niño phenomena – droughts, landslides and floods – every century or so caused such widespread disruption that entire dynasties could perish.

On the ‘floating islands’ there was an overpowering smell of rotting and fermenting vegetation. Walking around the islands was like negotiating endless puddles on a muddy lane. The novelty of an unstable surface did not give the same tactile pleasure as bog-moss or sand, for one’s feet neither bounced back nor felt any resistance. They just sank a little.

The islanders led a wretched life, their existence centring around the arrival of the local tourist boat from the mainland and desperate attempts to sell crude handicraft and weavings. The schools (there were three, all run by Seventh Day Adventists) were the only buildings with corrugated iron roofs – the others had more of the decaying reed.

‘The mountains of Eastern Peru, where the cloud-forest washes up the sides of the Andes from the Amazon.’

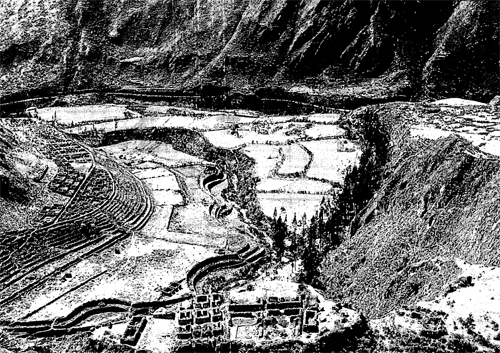

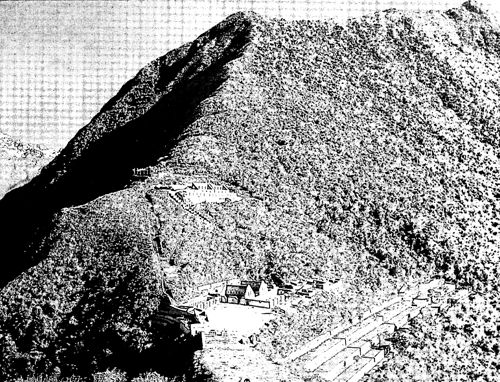

The Cusichaca camp, near the confluence of the Cusichaca and Urubamba rivers, with the site of Huillca Raccay in the foreground and Patallacta to the left: ‘It was the Inca world in miniature and it was to be the base for all our future exploration.’

Cuzco: ‘From the great central square, roads radiated out to the four quarters of the Inca empire, Tahuantinsuyo.’

Struggling up at altitude, with the Vilcabamba range behind me.

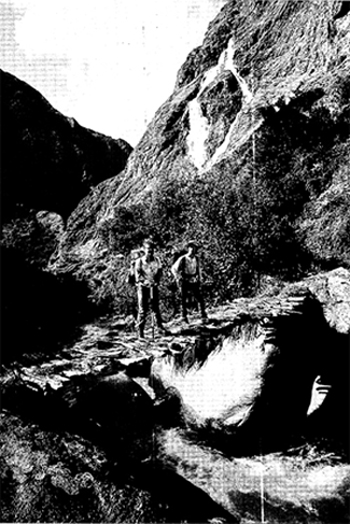

With J.B on a bridge over the Rio Aobamba after descending from Llactapata.

J.B. getting his breath back on the pass above Yanama, on the way to Choquequirao.

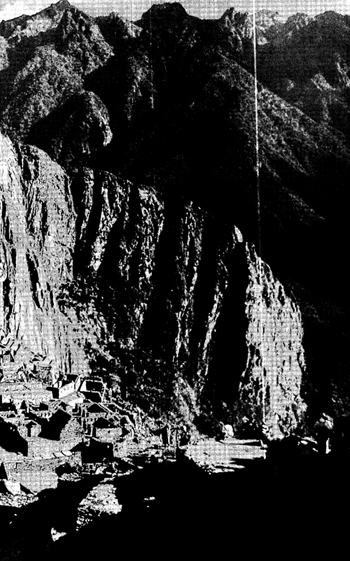

The view from Llactapata: ‘The unmistakable outline of Machu Picchu was folded over the distant skyline.’

Villagers at Rayanpata.

Choquequirao: the great kallankas of the Main Plaza as we first saw them in 1982, covered in undergrowth.

Following Page

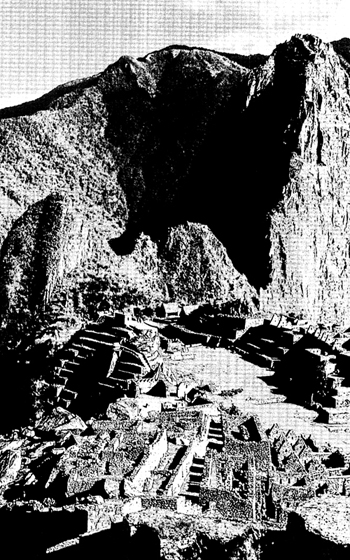

Machu Picchu.

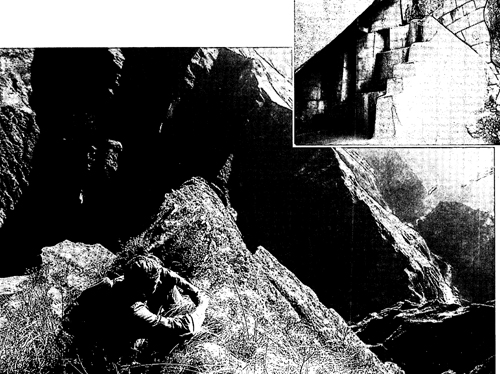

Machu Pichu: the area under the Torreón, which Bingham dubbed The Royal Mausoleum: ‘a receptacle of pure sensation.’

Roddy on the ‘eyrie’ beyond the Outlier Group at Choquequirao.

Choquequirao in 1999, after clearing and restoration. The kallankas of the previous plates can be seen beside the Main Plaza.

I wondered what Swift would have made of it. This would have been a fitting destination for Gulliver, with plenty of scope for parallels to be drawn – men forever trying to shore up the ground they walked on.

By contrast, the little island of Taquile, further out beyond the bay, was a far more hopeful analogy for the human condition. Everything was in harmonious proportions. An island about the size of an English parish, on mercifully firm ground, it had enough hillocks to have ‘hidden places’ and enough people to be prosperous without intermarrying. The land was quite fertile enough to live off without tourism and the islanders had worked out a sensible communal arrangement for taking visitors. There were no hotels so each family would offer accommodation on a rota system. Nor were there, as the islanders pointed out with considerable pride, any thieves or dogs. Certainly there were no police, and the only goods I saw being sold were all worked with impeccable craftsmanship. The islanders lived mainly on fish and vegetables, with little meat. Their traditional dress was flattering – loose trousers, a rough white shirt, black-and-white waistcoats, a red cap.

Both men and women would spin continuously, using small hand looms, and did so even when they walked around the island. I would meet them as I circled the entire shoreline in a few hours and climbed the little summit hill, from where you could see the patchwork of small allotments spread over the island, divided by simple stone walls. To prevent footpath erosion (for each small plot was only about fifty square yards), the island was translaced by carefully walled paths, paths that sometimes contoured, sometimes darted down to the water’s edge and sometimes went up and around the small hillocks, like cut apple peel. With the lake beyond, it looked like a Mediterranean idyll.

The boatman I was staying with, Fortunato, had lined the walls of his adobe hut with bamboo and I slept on a pile of rugs in the centre of the room, with a candle to write by as there was no electricity. His children would sometimes come in, both to watch me writing (which they felt was an odd occupation for a grown man) and to ask for one of the oranges I had brought from Puno. My only problem was that few of the islanders spoke Spanish, keeping to Quechua, of which I understood little. This would have been the savage twist for Gulliver – that having arrived at what seemed, in microcosm, to be a perfect balanced society, the Houyhnhnms, he was unable to communicate with them. Lévi-Strauss had a similar parable of the perfect uncontacted tribe in the Amazon who, while a paradigm of all that the civilised world wants the ‘savage’ to be, were unable to communicate any of their knowledge to their finders, as their language proved impenetrable.

It was with real regret that I left after a few days, and considerable relief that I arrived back in Puno. The crossing of the lake was not a good one. When we left, there was sun on the island and the islanders waiting on the curved jetty were silhouetted heavily against it, like symbolic figures. Once underway, however, a storm quickly began. In a small boat on a big lake this was no joke. We began to pitch. The captain was disconcertingly alarmed and brought out a large pile of oilskins and life-jackets, but rather than issuing them to the passengers, these were lashed to the stern in a heap. One of the islanders told me that the last time there had been a bad storm, the ferry had sunk only a hundred yards from shore and five people had been killed – not helped by the fact that, like so many islanders in different parts of the world, they had never learnt to swim. In the distance we could see the two lighthouses that marked the approach to Puno, winking alternately as if in complicity at our plight. We still had some way to go before we reached them.

I like the sea and have since made films about off-shore sailing, but that trip across the inland lake of Titicaca remains a low point. It was not so much the height of the waves, although the pitch was extreme, but the feeling of total insecurity. The light day boat we were in wasn’t equipped to deal with storms. Some of the plastic fittings ripped off in the wind. A woman started to cry. The water was dripping from the roof as the passengers huddled together in the tiny, rolling cabin.

Up ahead beyond Puno, the sun was setting in a red gap between the black storm clouds. The reeds to either side of the lake were being lashed by the wind, looking like fields of wheat that had been trampled on. It was with a communal feeling of thanks that we finally passed through the channel between the lighthouses. An Italian man who had been staying on the island with me said a prayer. I needed a drink.

I had got talking to three Swedish girls on the boat, day-trippers, who were reserved when I first saw them but became more approachable under the duress of imminent shipwreck. One was tall and striking-looking, with a Garbo profile and blonde hair. After months in the mountains and on my own, this seemed an unfair provocation to my deprived hormones. That night I went with them all to a small Peña, a folk-club, where we were serenaded with the song ‘Abra la Puerta’ (‘Open the Door’): this turned out to be the plea of a despairing man who needed to enter a house not, as I at first assumed, for his girl, but in order to get a drink. An Argentinian guitarist came on who was introduced as being deaf: he played with ferocious intensity, hunched over his guitar and stopping frequently for taut moments; he even played ‘El Condor Pasa’, turning it from the over-familiar pan-pipe lament into something with the emotional lacunae of a tango.

I tried chatting to Garbo, but she preferred to let her smaller brunette friend do all the talking. After a while, what with the noise and the difficulties of speaking in Swedish English, I concentrated on the music and the excellent ponche they served, a mixture of hot milk and pisco brandy.

Garbo and the third girl peeled away back to their hotel, leaving the brunette and me. It was only when she put her hand on mine that I realised, with the usual male slowness, that I had very discreetly been ‘switched’ without realising it. I also realised, now that Garbo wasn’t casting such a shadow, that the brunette was extremely attractive in her own right. Unfortunately the ponches chose that moment to kick in savagely, with the slight delay and extra potency that altitude seems to encourage, and it was all I could do to get back to my hotel, let alone take anything further. I woke up with a hangover and considerable regrets (how often in life was one going to meet an available Swedish girl high after a life-threatening experience?). But at least the boat hadn’t sunk.

*

Later that day I became more seriously ill and remembered the last time I was ill after one of those same ponches – from the milk rather than the alcohol (I thought of the Arctic explorer who alone among his crew never got ill because he refused to mix his whisky with what turned out to be contaminated water). I got onto a serious antibiotic diet and rested for a while before heading on towards La Paz.

When I finally hauled myself onto the bus, I found an engaging Dutch anarchist called Alfred. He was a welcome relief after all the South-America-by-numbers travellers and a good companion for the journey to La Paz. I had already met him wandering around Puno market: at six foot five, with bleached hair and a nose ring, he stood out, to say the least. He was in the process of buying a heavy-duty catapult – to use, so he said, in the Amsterdam street battles that he and his squatter friends fought with police. Alfred had worked there as a male nurse, but the constant carrying of patients had damaged his back and after cashing in the insurance he’d started travelling the world – albeit very slowly. He had spent six months just in Nicaragua, before heading south.

Alfred’s main comment on Nicaragua was how wonderful it had been to have such a thriving black market in dollars – not perhaps a particularly left-wing sentiment, but he reminded me that as an anarchist he didn’t need to follow any dogma. This was what was luring him to Bolivia now. ‘The exchange is going through the roof,’ he cackled with delight. ‘We’ll be able to live like kings.’

Within a short while we were over the border into Bolivia.

*

The name Copacabana was precisely right – a pastiche name for a resort town, a friendly place on top of a hill, looking out over the Bolivian side of Lake Titicaca. It bore about as much resemblance to the Brazilian beach of the same name as Bournemouth does to St Tropez. I felt as if I were suddenly on holiday, in a new country and with different food: there were delicious salteñas in the market, hot pasties stuffed with chicken or egg, and I washed them down with api, a kind of teetotal punch.

Alfred and I established ourselves in a sleepy pensión near the waterfront run by a Señor Ramón, which had chamberpots in the rooms and a decayed balcony looking out over Lake Titicaca. Señor Ramón took one look at us and stated the house rules with all the firmness of a Blackpool landlady: ‘No drinking in the rooms, and no women – or you’re in the street.’

It was a Sunday, and the weekenders were out in force: pleasure cruises were coming back from the Islands of the Sun and Moon, while a photographer was using a box camera straight out of Lumière to take pictures of Bolivians in their Sunday best. The odd kid bicycled along the shoreline. A large family gathering had spilled itself over the shores of the lake, the women bowler-hatted, the men in racing trilbies, and beside them were packets of food in white muslin waiting to be opened. It was a nineteenth-century scene, some Breton seascape for a Boudin or a Monet.

A full Bolivian admiral was promenading with his family, in a magnificent uniform with enough medals to have their own auction at Sothebys. His family kept a discreet ten feet behind him. The admiral probably felt he had to make up in attitude for the lack of any sea-going fleet. The Bolivian navy had been sadly curtailed ever since the War of the Pacific a hundred years before, when the country had lost all access to the sea (Chile had taken the Atacama Desert from them, with British assistance). They now had to make do with elaborate ceremonies on land and the odd ride over Lake Titicaca to scare the smugglers, for whom the political division of the hundred-mile lake was a contrabandists’ charter.

The Copacabana Cathedral was as ornately decorated as the general, Byzantine in style and with a magnificent mosaic roof. Inside the bishop shuffled along with the liturgy: it was only with the sermon that he became rhetorical and forceful, knocking the gilt psalter over in his excitement. It is difficult for the Spanish language to achieve the powerful plainsong effect of an English liturgy, being too inflected, and so church services often oscillate between hastily mumbled intonation and full-blown rhetoric. However, the Church is a powerful force in the Andes. After the violence of the Conquest, the two cultures discovered they had much in common when it came to religious temperament. The mordancy of the Spanish met the fatalism of the Indian, and the resulting combination is a powerful one, a peculiarly Andean form of Catholicism that mixes a fierce eschatology with pastoral images of the cantuta flower and the lily.

Beside the cathedral was a simple capilla de velas (‘chapel of candles’), a narrow concrete trench of a place with a darkened Christ figure at the back. Compared to the gilt and pomp of the cathedral, it was a humble affair. Worshippers had lit candles for the difuntos (a fine Castilian word for the deceased), and also for their patron saints. A woman I had met on the bus came over and poured her heart out to me: she came here regularly as a pilgrim, she had lost her husband, this time she had come with her eldest son, the next day was a fiesta so she had been able to come over from Cochabamba for a long weekend, they had a fiesta there in March when childless men prayed for children and men with too many children prayed they would have no more.

We were interrupted. Outside the usual Sunday brass band had been parading, although with more of a military presence than I was used to in Peru. There seemed to be soldiers everywhere. Suddenly one of them produced a machine-gun and fired off a round into the air in front of the cathedral. If this was to attract attention, it was spectacularly successful. The noise was deafening. Some kids ran forward to retrieve the spent cartridges off the cathedral steps. The soldiers, satisfied that they were now being noticed, continued on their way.

I had known that Bolivia was in political turmoil, but this helped focus my attention. Later that day, over some beers that we had smuggled into the pensión past the disapproving eye of Señor Ramón, Alfred gave me his critique of the Bolivian political situation.

‘The generals want to give up power – by force if necessary.’

I thought that Alfred’s usually excellent English had failed him. ‘You mean “take power”.’

‘No, give up power. The situation has become so impossible to manage that the generals are prepared to force the democrats at gunpoint to take over from them. Of course the democrats don’t want to run Bolivia any more than anybody else wants to. This country is impossible, you see.’

Alfred clearly relished its impossibility. Bolivia was the role-model for an anarchist state. It was said to have had over a hundred changes of presidents in the past century. Now the military government had closed the banks and tried to limit foreign exchange to a few government agencies, trading at a fixed rate. It was an invitation to a thriving black market, as I realised when changing a few sucres outside the bus station, a traditional spot for moneychangers. The sucre was named after Antonio José de Sucre, the very first of Bolivia’s many short-lived presidents and a man who had done as much as Simón Bolivar to throw the yoke of Spanish colonialism off the continent.

I could afford to travel in a luxurious leather-seated Pullman rather than the bone-crunching wrecks I was used to: we pulled out of Copacabana and the narrow ridge road wound across the Tiquina peninsula that juts out into Lake Titicaca. The road was a delight, slipping and sliding across the top of the ridge, with alternating views of both sides of the lake and the small fishing communities that dotted the shore. There were oxen grazing in the shallows of the water.

I sat next to a fit and brisk looking mestizo in shirtsleeves who pointed out to me with some relish the small island where Bolivian prisoners were incarcerated, a ferociously humped Alcatraz that looked menacing even at some distance across the lake. This was Coati, the Island of the Moon.

The Incas made pilgrimages along the peninsula to visit both this and the nearby Island of the Sun. On the Island of the Moon, they built a convent for mamaconas (‘holy women’) which directly copied many of the features of the earlier Tiahuanacan buildings already on the island, like the step-motif which was to the Tiahuanaco culture what the trapezoid was to the Incas. Some Inca legends described the Island of the Sun as their birthplace and one could see why it would fit so perfectly into their aesthetic – the high lake (an altitude of over 12,000 feet), ringed by mountains, with excellent sight-lines and legitimised by the worship of an ancient culture whom the Incas admired.

I felt the heat on my face from a few days sun-bathing by the lake. My body was still feeling the powerful antibiotics that were working their way through my system. The inside of the bus was like a furnace. It would have been a brave gringo who attempted to open a window. Andean peoples may be forced to endure a cold climate, but they still hate it, just as in India the inhabitants complain endlessly about the heat, and the mountain coaches were always compensatory fugs of condensation and stale air as a result. Sitting in the central back seat, I was staring straight down the length of the bus at the neon display over the driver’s windscreen, which was flashing ‘Dios es Amor’ (‘God is Love’) at me in saturated red. The driver sounded the horn by pulling on a bell-rope suspended over his head – and he sounded his horn at every corner, car, truck, dog or sheep.

My companion started to talk to me about the dollar rate (not surprisingly, a national obsession). I worried at one point if he was going to try to change money for me, but instead he told me, very usefully, how to exploit the situation – where I could get the best black-market rates for dollars, where the best markets for contraband were in La Paz. After a while I asked out of politeness what he did. ‘I’m a customs official.’

We came to Tiquina and the straits, the narrow section of water dividing the northern and southern halves of the lake, which the customs man was prompt to tell me ‘have a depth of over 800 metres’ (Latin Americans love statistics), and a curious crossing began in which the passengers were transferred separately onto small launches while the coach itself was strapped onto a large raft. Once over the straits, the Bolivian Altiplano widened out in front of us. After months of being in the narrow Andean valleys, it was like finding oneself on a prairie, albeit one at 13,000 feet. The horizon was made even emptier by the few houses scattered across the plain like broken building bricks, their brown adobe walls even drabber than the land. I found the Altiplano desolate but not in a spectacular way – it seemed rather to be the landscape showing its complete neutrality and indifference.

Beyond the lake, I had already seen the Cordillera Real rearing up. The first sight of a mountain range from afar is always a deceptive one (I remembered when we had first flown over the Peruvian Vilcabamba on arriving in Cuzco). A new range can seem both more anonymous and more clearly visible than when one gets entangled in the valleys and each mountain becomes a looming presence, often unseen behind a cloud or ridge. It felt wrong to see the mountains so exposed – they seemed naked, lit by the bleak afternoon light of the Altiplano.

It was a stage-drop suitable for what was the bleakest passage of all in the Spanish Conquest of South America. If Peru had seen the climax of the conquistadors’ achievements (victory over a powerful Empire had at least been a brave achievement, if a brutal one), Bolivia saw the squalid end-game, the almost Beckettian reduction of their aims to the annihilating extraction of wealth, whatever the human cost, where the only words to be heard were ‘More silver, now.’

When the original conquistadors had set off with Columbus in 1492, they carried with them some of the aspirations and ideals of the Renaissance they had left behind. They searched for wealth and glory as well, of course, but it was also true that some saw the New World as a canvas in the same way as the ones being painted in Rome and Venice, a setting for the best in man to emerge. For the humanist, America could be seen as an Arcadia, a Golden Age setting as envisaged by the classical sources that had only just been rediscovered.

Likewise, many of the first wave of Christian missionaries who went to the West Indies and Mexico genuinely thought they were converting lost souls, re-establishing a prelapsarian state in a land where God had clearly been bountiful in his distribution of riches. The natives, wrote the great campaigner Bartolomé de las Casas, were ‘tablas rasas’, ‘blank slates’, on which a new faith could be inscribed.

Thus Cortés, in conquering Mexico, could mythologise his achievements into a compendium of dashing military conquest, religious conversion and fairytale wealth. His letters back to Charles V are full of optimism about the ‘New Spain’ he had established. Thirty years later, by the time the silver mine of Potosi was found in Bolivia, much of this early idealism had fallen away. The Spanish could no longer play at being romantic heroes in some chivalric epic – now they were not dashing conquistadores but landowners, extracting as much as they could from Peru and shipping it back to a mother country which increasingly distrusted their attempts at independence. The priests had made the disillusioning discovery that the natives of the New World were remarkably like Europeans in their capacity for sin and moral turpitude – and that far from being ‘tablas rasas’ for a new re-birth of Christianity, they held deep religious views of their own that were almost impossible to erase or at times even recognise, such was the cultural gulf between master and servant race. This feeling of increased disillusionment, of a dystopia, was to reach its apotheosis at Potosí.

Potosí was one of the richest silver mines that has ever been discovered. At first the silver was so plentiful that it lay on the ground and could simply be gathered by hand. Around 1550 the Spanish began extensive mining down into Potosi hill, the Cerro Rico or ‘Rich Mountain’. Indians were brought forcibly from hundreds of miles away to work the mine. A horrific number of them lost their lives.

The image of the mine as described by contemporary witnesses seems Dantesque, the great central shaft of the mine descending endlessly into the mountain, with three crude ladders hung from the sides: a ‘down’ ladder, an ‘up’ ladder and a third for use if either of the other two broke, as they frequently did. The Indians would carry enormous loads from the perpetual darkness at the foot of the shaft – one authority quotes 45 kilos, a tremendous weight (even a fit Himalayan porter will rarely carry more than 25). As many as 4500 men could be working in the mine at any one time, with twice that number waiting outside to take their turn. The mine consumed the labour-force of Bolivia’s Altiplano. If they didn’t die, they were ground down by the apology for a wage that was paid to them. Within a generation, the population of those parts of the Altiplano used for mine conscription had halved. Within another generation it had halved again. And still Potosi continued to exact its quota.

Any pretence that this was being done voluntarily by the Indians – a pretence that had been sustained at some of the lesser mines elsewhere – was simply washed away by the enormous wealth that Potosi created for the Spanish Emperor, a wealth which fuelled further misery in Europe with the prosecution of Spain’s European wars. Potosi is a terrible reminder of how the Dark Ages continued past the Renaissance and of how the Spanish Conquest ended. It was to the sixteenth century what Auschwitz was to the twentieth. The great Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano put it succinctly in his book Open Veins of Latin America: ‘Potosí remains an open wound of the colonial system in South America: a still audible “j’accuse”.’ Much of the sadness and instability of the country seemed still to well up from the destructiveness of that early greed.

*

We seemed to circle around the rim of La Paz before finally dropping into it: it was an odd vertiginous feeling to be in the suburb of a city and look down over a precipice at its centre. I was used to city centres only revealing themselves from the tops of skyscrapers or spires – La Paz alone seemed to resemble a plug-hole into which the whole city drained.

‘Dios es Amor’ was still blinking at me in red from above the driver’s seat. It was twilight and the bus was alternately flashed by the city’s sodium light and the washes of coloured neon from the shop-fronts. We stopped at some traffic-lights and hawkers came by with newspapers, which the passengers bought anxiously to read about the political situation.

Alfred was looking very wired, either from amphetamines (his nurse’s duties had left him with a collection of chemical habits) or from the impending excitement of possible street violence and confrontation. I had already heard and wearied of his many stories of fights with the Amsterdam police. ‘This revolution will not be televised!’ he announced suddenly in a loud voice. The Bolivian passengers looked startled. There was already an odd, tense mood in the bus as we circled down through the empty streets.

Outside the diaspora of the bus station, the dim figures of street-sellers and commuters swirled by us in the dust. A big car pulled alongside us. ‘¿Dólares?’ The thick-set Bolivian inside had seen too many Hollywood movies. He was wearing a trenchcoat. Short of having a sign on the roof saying ‘Black Market Exchange’, he stood out a mile. I received an obscene amount of money for just a few dollars. ‘Let’s go drink to the death of capitalism,’ said Alfred.

There was a roof-top restaurant at one of the hotels that was said to be one of the best in the city. The maître d’hôtel looked in horror at my battered backpack and Alfred’s dyed blond hair and nose-ring. But he was in no position to turn us away. We were about the only people left in La Paz who could afford to eat out. Around us were a few other travellers who looked like they couldn’t believe their luck. ‘This is even better than Nicaragua,’ said Alfred appreciatively as he ordered the largest steak they had.

It left me feeling uneasy. I checked into the sort of hotel I normally went to, downtown near a market, and left Alfred to his luxury suite. I fell asleep with the scurrying of city traffic below and an unexpected full moon shining down on me, as if blessing a lost orphan.

*

La Paz was a small city with a small centre. I quite often ran into my friend in the big black car and the trenchcoat over the next few days. He would cruise up behind me and idle along until I noticed him. Because it was pointless changing more than a few dollars at a time (the rate would have doubled by the evening), I needed him: the official exchanges were usually shut or trading at yesterday’s money and the business of continual inflation and trading up prices was addictive. Sometimes he would have a woman beside him, wearing bright-red lipstick and playing moll to his gangster. She would count out the money. Trenchcoat (I never asked his name) was my only reliable source of information about what was happening. I knew a curfew had been declared and that the military were on the streets, but that was all. The newspapers were useless. In my hotel the staff knew nothing (instead the bell-boy asked me to record some passages from Graham Greene onto his tape-player so that he could listen to them for his English course).

Political correspondents reporting on a coup are usually close to the sources of information and each other, so can follow the rapid political changes of a crisis hour by hour. But for the actual inhabitant or less informed foreigner in the middle of a coup, for those on the ground, the process is continually hidden. In La Paz in the autumn of 1982, the newspapers didn’t report what was happening, the television was a closed circuit and the only copies of Time were weeks out of date. No one I knew had a short-wave radio to listen to a foreign station – and if they had, would not necessarily have heard that much. Another coup in Bolivia was hardly news-worthy.

I discussed the situation with Brian, an Australian car-battery salesman who had taken time off to travel the world and was bemused that he had ended up in a coup that was bloodless yet also paralysing. ‘I wouldn’t mind it if there was anything to bloody do,’ he wailed. This was the problem. Even the limited range of activities that travellers kept themselves busy with – hanging out in cafés, trying to negotiate the Byzantine complications of the poste restante system, haggling for souvenirs – were denied.

One day I watched as ‘a general and indefinite strike’ took to the streets, called for by the trade unions who, despite (or because of) a history of exploitation and corruption since Potosí, had become a strong voice in Bolivian politics. The strike was proclaimed from the Plaza San Francisco and spread with impressive speed into every working sector, both public and private. To the Bolivians it made little difference that most of the shops were shut – they had reached the position where they couldn’t afford the goods anyway.

The only outward sign of any political urgency was the shrill ‘Ultima Hora’ cry of the newsreaders, usually choked off into ‘Hora’. Each edition told as little as the previous. The strike had turned La Paz into a dead city. I watched as some riot police set up a barricade; they seemed embarrassed and were trying to stop their Dobermans from barking. One Doberman defecated right in front of the barricade and a policeman stepped forward with a scoop to remove it.

La Paz was a city drawn in charcoal, with washes of brown and grey. The clear light of the Altiplano above seemed to have sucked all the colour out of it. Just by the market and my hotel were rows of soup-kitchen stalls, smoking in the dark like some image from Depression America. I would eat chairo there and watch as the Tránsito, the officious transport police, patrolled the soup-sellers in their long, khaki, buttoned-down overcoats for any signs of sedition. There were police and military of every sort and it took a while to learn how to distinguish them. Once I passed a stall selling masks of gorillas in different types of Bolivian military uniform: although incredibly ugly, the gorilla masks were intended as a sign of masculine strength and were done affectionately rather than pejoratively.

In the streets, the women sat immobile for hours over a pocket handkerchief of goods – a little pile of bootlaces, or rolls of toilet paper – for returns so minuscule that it broke my heart. Bowler-hatted and impassive, they seemed a Latin caricature of English reserve.

Coming down from the Prado, I crossed the end of a big demonstration march by the opposition Left, a hunger march, and followed them towards a large square. The crowd was too big to fit in the square itself and funnelled backwards into the narrow streets. An amplified speech echoed around the walls, distorted by a bad microphone and feedback so that it was impossible to make out any words. Rival trucks were circling the city with megaphones. I felt like I was sitting right behind the speakers at some very bad festival, without being able to see the band.

It was difficult to tell when (or if) the crowd’s jostling and whistling stopped and an actual riot started. Suddenly there were police coming towards us and people running away. The police had gas canisters strapped to their belts. A kid with some scales was screaming, ‘Pésense, pésense, tienen que saber su peso’ (‘Weigh yourself, weigh yourself, you must know your weight’). In the mêlée along the narrow side-streets, I was sometimes unsure if people were hurrying to get away from the police or just to catch a bus to get home. Everyone always hurried in La Paz. It was a cold city. Later I learnt there had been some savage beatings of the demonstrators.

The army curfew meant that I was holed up every evening in the little hotel by the market. I had been carrying Lévi-Strauss’s Tristes Tropiques around with me since the start of my travels, but had always resisted reading it. Given the notoriously circular and somnambulant style of the book, being confined to a small room by military action was one of the few ways I was ever going to do so. It was worth it, for Lévi-Strauss had flashes of brilliance that punctuated the book’s occasional monotony and in his overview of a decaying world slowly becoming more and more homogeneous, a ‘mono-culture’, he made me realise how much more precious those areas of true difference – like the culture of the Incas – were to become.

I could hear the lorries with their amplified and distorted speeches patrolling the streets long into the night as I read of Lévi-Strauss’s expeditions into the interior of the Amazon in the thirties, his nights spent with a tribe sleeping in the ashes of the fire they had lit, the bees which could lodge themselves in a man’s nostril, trees that smelt of excrement, and the slow distillation of all these memories as he wrote the book twenty years later.

Paradoxically, given the famous opening (‘I hate travellers and explorers’), the book is one long and intense meditation on the need for both travel and exploration, even if he argues that exploration should be as much mental as the physical crossing of a space. His own mental travel can be, to say the least, circuitous, and reading the book at times felt like travelling up a particularly turgid Amazonian tributary. Just when I was about to give up on him he would produce some brilliant firework of a thought that would irradiate the page – often a thought that ran completely counter to what he had previously been arguing. For a man who could say that ‘the first thing we see as we travel around the world is our own filth, thrown into the face of mankind’, he was also prone to an extreme romanticism: ‘Dreams … have always slipped through my fingers like quicksilver.’ The mixture of world-weary traveller and poet was intoxicating.

He also helped me define one constant of my own travelling experience – that travel is the perpetual difference between what you expect and what you get.

I couldn’t leave La Paz because of the strike and the only book I had was Tristes Tropiques. Inevitably I resorted to the restaurants. I ate my way through the menus of the fine clubs of the city – and there were many of them, tucked away down side-streets and with verandas looking out over the city, often decorated as if in a parody of a gentleman’s club, with leather armchairs and prints on the walls: the Club Hogar Austriaco (the Austrian Club), the Club de la Paz, the Club de la Prensa, the Club Alemán. All of them had a declining roll of members, peeling wallpaper and furniture that was too large. They felt like a Hapsburg had died in them.

It was in one of these clubs that I met Felix. I was his sole customer and, as there was only so long you could read Tristes Tropiques on your own in an empty restaurant, we fell to talking as he served me the long lunch that was the standard fixture at such clubs: the aperitif, the hors d’oeuvre, a soup (lobster was a favourite, although I tried not to think where it had come from), the segunda (the entrée), and finally a groaning trolley of deserts. My only strength of will came with refusing the liqueurs that Felix would always press on me.

Felix looked as if he had been there as long as the furniture, but I discovered that he had travelled extensively as a young man and had worked in many different European restaurants: ‘I always got work because my comportment was correct,’ he told me proudly. He stood upright, with a shock of white hair and a face so grained and mottled that it stood out against the smooth pressing of his shirt and suit. His Spanish was some of the most formal I had ever heard and I kept trying to keep up with the elaborately courteous phraseology. ‘Would you, Sir, desire some wine with your meal?’ he would say as he showed me a leather-bound volume that groaned with musty Argentinian and Chilean vintages. Even when I ordered a pisco with ginger ale (a chaufflay), the rough solecistic equivalent of ordering a Babycham, he would take it on the chin without a flicker of disappointment at my failure to single-handedly keep the flame of Bolivian gourmet dining alight.

He had worked in the Netherlands, in Italy, even in the Tottenham Court Road, but the place he remembered most fondly was Basle. I asked him if he had ever been to the mountains when he was in Switzerland and he shrugged politely, as if to say why on earth should he have, given that La Paz itself was higher than many Alps. He was, however, terribly impressed by the Swiss. When he mentioned them he always made a gesture straight ahead, as if to say just that: ‘Los Suizos fueron siempre muy rectos, the Swiss were always very correct.’ Then he would shake his head and mutter about ‘la situación’, as he called the political impasse. ‘Things aren’t right at the moment. There is no respect. Sir, would you like the crème brûlée or the diplomats’ pudding?’

Every day I would return to Felix and his steaks done ‘a la inglesa’ (‘English-style’ meant medium-rare for some reason), and he would tell me more of his travels and of those who had not appreciated his manner, but were the poorer for it. One day he announced that the strike had finally been lifted. The assembly who had been elected a full two years earlier but had been usurped by the military could now finally take their seats in government, led by Hernán Siles Zuazo, one of those who had instigated the land reform movement of the 1950s.

I could leave La Paz.

*

Looking back from the bus, La Paz looked like a premonition of a moon-city, packed into craters, rent by fissures and cracks, a red-and-brown terrain. The journey became more lunar as we travelled east, a desert landscape unlike anything I had ever seen. There was not even a cactus to relieve the wide expanse of red-brown rock and dust-bowls, with Mount Illimani looming up ahead of us.

I was heading for one of the old Inca roads that I knew descended towards the jungle, a spectacular path called Takesi that fell from a 15,000 feet pass down to an old mining village some 8000 feet below. It was good to get out of the city. I had felt myself starting to get corrupted by my artificial wealth (eating fine meals while out on the streets there were hunger marches) and there had been an incident that had crystallised this the day before I left.

One of the few other guests who had been marooned with me in the hotel was a Bolivian woman in her forties or fifties. I had found a watch left in the communal shower, a cheap watch with a plastic strap, and guessed it might belong to her but wasn’t sure. I took it back to my room, meaning to hand it in to reception, but then absent-mindedly forgot about it. Later that day I was sitting reading when I heard a commotion outside, with the woman claiming that I had stolen the watch, that I was a ‘delincuente’, that my room should be searched. The management hammered on the door. I panicked, opened the window and threw the watch as far as I could out of the window. It was not exactly my finest hour, but there was something in the city that was beginning to get to me, a state of moral inertia.

Getting back on the trail was a good corrective – and now that I was travelling on my own, with the same tent and stove but no one else to help carry it, this would be a truly Calvinist shedding of any excess fat.

If this was a pilgrim’s progress, I had hardly taken two steps before being way-laid by Temptation, in the form of an engaging, moustachioed Argentinian called Antonio, who turned out to be the controller of the local coca industry. He first stopped me to sell some gold that one of the locals had panned out of the river, but we fell to talking and quite soon I abandoned any thought of walking further that day. He was at the legal end of the coca business – some was allowed to be grown on a quota basis – and had some interesting stories about the smugglers (he himself had elaborated a cunning scheme where he traded any confiscated ‘non-quota’ coca leaves for gold). He also had the first bottle of whisky I had seen in months. It was a compelling mixture. I had been fascinated by the mythology of coca ever since my induction by Presentación and here, clearly, was the man to tell me more about it.

The irony involved in the whole business of coca leaves was so big that it was easy to overlook. Here was a product that provided the recommended daily allowances of iron, calcium, vitamin A and phosphorous, just like it says on the cereal packet. It also gave enormous stamina to those Indians working in the extreme climate of the Andes. For centuries it had been one of their few reliefs from the cold, the mines and all the small potential miseries of daily life. In its natural state, as ingested by them (either by chewing or in a tea), it had no addictive qualities, only positive ones. And in lower climates, it was even easy to grow, potentially providing three good harvests a year. The coca plant, or Erythroxylum coca, to give it its botanical name, was a dream crop and a dream product.

In a different world, the West would have been actively encouraging Andean peasants to cultivate it and coca tea would be promoted as an effective, healthier alternative to our more normal caffeinated varieties. Yet because of our perverse taste for cocaine, a highly processed product of Erythroxylon which contains less than 1% of the actual coca leaf, the whole plant had been tarnished. The United States had poured money (and threats) into the eradication of the crop. Such was the hysteria surrounding the drug and its derivatives like crack that the States had even made it an offence to import coca tea into the country – as absurd as arresting people for drinking camomile. It was miraculous that Coca-Cola, which had originally promoted itself heavily as a ‘healthy drink’ because of the coca content, had somehow managed to maintain a licence to export the leaves from Peru.

Coca-Cola’s involvement had prompted all sorts of elaborate conspiracy theories from some of the long-haired gringo trailers who had hung around the bars of Cuzco. One Canadian had held forth at length to me about it over breakfast in the Wiracocha café: ‘Think about it, Hugh. Coca-Cola are only allowed to export coca leaves if they extract all the cocaine first. Now what do you think happens to all that cocaine they extract? Do you think it’s just sitting in some locked customs warehouse in Callao?’ He leered. ‘Why else should the CIA bother with trying to run down the illegitimate cocaine smugglers if not to help boost their own smuggling business? The CIA, Coca-Cola, ITT, they’re all in it together.’ It had been too early in the morning to argue the case with him. (I found nothing sadder than to hear these same travellers muttering over their beads about how the real psychedelic high was to be had from sniffing datura lilies.)

What was certain was that attempts to close down on the trafficking were leading to some very strange happenings in the more remote jungle. Antonio told me a little about the wilder side of things as he stroked his moustache and managed to imply that while he knew of these things intimately he was at the same time distant from them.

Now that the Americans had more or less managed to close down air-traffic in the drug, the dealers had turned to the remote rivers on the far side of Peru and Bolivia, with their 8000-mile network of Amazonian tributaries. It was almost impossible to stop the dealers getting shipments of coca leaves to Colombia by the back door, where they would be processed into cocaine. In a wonderful example of military-speak, the senior US commander in Latin America had said, ‘Riverine interdiction is the heart of the next important step in disrupting the supply.’

To help ‘riverine interdiction’, the Americans were providing Bolivia and Peru with a hundred patrol boats outfitted with M-60 machine-guns, together with satellite-linked tracking equipment. US military personnel were also using planes to guide local forces in the water below. But as another American official candidly admitted, this time off the record, ‘What we are talking about is impossible to control, over areas that the central governments have never controlled.’ Antonio put it even more succinctly: ‘It’s wild, wild country. You could float a circus from here to Colombia and nobody would notice.’

Coca leaves had always been fought over, even in the time of the Incas. The Emperors had sometimes given symbolic presents of a bunch of coca leaves to conquered rulers, a gift that was double-edged, as it was a sign both of benevolence and of the less symbolic and extremely onerous gifts they expected in return. Substantial amounts of coca leaves would have been part of any tribute given by a lowland tribe.

I had already come across examples of poporas in museums, the ceremonial coca-dippers which nobles would have used to break down the leaf with an alkaline substance for chewing. They were elaborate affairs and a reminder that for the Incas coca was a jealously guarded royal prerogative, although it is hard to see how they could have restricted its use, given the ease of cultivation and consumption. Coca leaves were burnt at religious ceremonies as a demonstration of conspicuous and extravagant waste (they are still burnt by the people of the mountains as auguries for the weather).

With the coming of the Spanish, the use of coca leaves was no longer restricted and the wider population took it up with a vengeance in what must have seemed at first like a pleasing democratisation of an aristocratic pleasure. However, the consequences were to be disastrous.

This was due not to any harmful side-effects of the drug, but to the greed with which the Spanish grew it. It had previously been cultivated in more low-lying areas as a specialist crop for the nobility and delivered in tribute. To mass-market coca, the Spanish now needed a considerably greater workforce and, given that there was little available man-power for them in the jungle, they pressed highland Indians into service. This had predictably miserable effects on the health of men unused to the diseases and diet of the jungle. Half of those forced to work in the cocales, the coca plantations, are thought to have died as a result. Despite attempts to limit the death-rate, the coca business, like tobacco today, was inevitably fuelled by the staggeringly good economic returns. For the conquistadors, coca was as good a trade as silver mining, and, unlike silver, the veins would never run dry. But its reputation as a danger to society was growing.

Coca had always been intimately connected with the Quechuan priesthood, and there were various ceremonies in which it was worshipped in pre-Columbian times. The arriving Spanish clerics were horrified by its perceived power over the nation and the process of its demonisation began – even the normally sympathetic Cieza de León thought it ‘a disgusting habit’.

John Hemming in his book on the Conquest quotes a commentator of the time, Diego de Robles, who declared, ‘coca is a plant that the devil invented for the total destruction of the natives,’ and the drug was officially condemned at the first ecclesiastical council of Lima in 1551. The US Customs Service and DEA would doubtless have concurred.

Yet the enormous and disruptive amount of money spent on trying to eliminate coca leaves in Peru and Bolivia – with very little offered by way of a replacement crop – was particularly absurd given the potentially far more effective use of the same money on prevention and rehabilitation work in the States. Cocaine was a problem of demand, not of supply. It was easier and more politically expedient to blame the peasants of the developing world than to try to address the acute social problems in American inner cities.

Given the enormous symbolic weight the leaves had come to acquire, I found it all the more moving to see the simplicity with which gifts of leaves were made, particularly on the remote mountain trails where quite often a few leaves would be handed over on the strength of a casual meeting and a feeling of fellowship.

There was a nice description of coca from the nineteenth century, by a Peruvian doctor called Hipólito Unánue who had prepared it for a lecture in New York, perhaps in an early attempt to convince the American public of its efficacy:

The Indians believe that the use of coca is indispensable. They must chew it or die. They find that coca is capable of restoring lost strength, of resisting the attacks of age, of surviving the attacks of the elements and at the end of the day of giving a real lift to the spirit in moments of anxiety so as to put aside the troubles of the world. Just as in The Odyssey when Helen prepares a drink for her guests:

‘Into the wine of which they were drinking she cast a medicine

of heartsease, free of gall, to make one forget all sorrows,

and whoever had drunk it down once it had been mixed in the wine bowl,

for the day that he drank it could have no tear roll down his face,

not if his mother died and his father died, not if men

murdered a brother or a beloved son in his presence

with the bronze, and he with his own eye saw it.’

It took me a while to get used to the process of chewing the leaves. Many travellers, particularly those expecting the instant gratification of a hit, gave up after a few attempts. The idea was to take the leaves very slowly into the mouth, one by one, and coat each with saliva before adding it to the slowly accumulating cud in the side of your mouth. This gave the chewer the comical appearance of a ruminating cow: I kept my chewing for tough treks, because that was when I really needed it and because no one could see me look stupid while walking ahead of me. The trick seemed to be in timing the amounts of bicarbonate of soda needed to break down the alkaloids in the coca leaves, without which nothing would happen. The Indians used a powerful alkaline substance made out of the ashes of cacao pods to do this. It was called tocra de montaña or more traditionally llipta, and could take the side of your mouth off if you got the amount wrong (bicarbonate of soda was safer for the ‘light user’). Then you swallowed the small amounts of green liquid which the leaves produced.

Disconcertingly, there was always a considerable time delay before any effect really kicked in and perhaps this was the reason why the Spanish, used to more instant satisfaction, never really took to it. (‘The Spanish use it simply as medicine, or when the inclemency of the hill stations inclines them to take up Indian customs,’ noted one early chronicler.) The results often only began two hours after you’d started to chew, so you could be left unsure as to whether anything was going to happen – but if it did work, there was a real lift and energising effect that could take you over mountains other soap powders wouldn’t. The cocada, as this was known, could last for an hour and the sense of anaesthesia and euphoria was very different from cocaine. Indeed, it would be hard to think of a less suitable drug to take in the mountains than cocaine, which, with its febrile bursts of energy and mild paranoia, would leave the taker exhausted after five minutes and petrified of possible snakes.

*

I needed all the coca leaves I could get the next day. It was not so much the ascent to the pass – although a steep one – but the extraordinarily heavy pack I was carrying. Used to having companions to share the burden with, I had badly over-loaded. I realised it was all getting too much when the kerosene bottle burst and flooded the rest of my belongings.

I gave half my food to the gold-diggers working the river below. A week’s work would produce six or seven grams for them, if they were lucky. Their main irritation was the groups of picnicking families from the cities who came along at weekends to try their luck at panning. ‘They’re such amateurs,’ one woman told me indignantly.

Above one village was a decaying church (the tombstones stuck up like matchsticks) and a group of bowler-hatted picnickers enjoying themselves. ‘¿Anda solito? On your own?’ they asked solicitously after laughing at my lack of Aymará, and offered me chuño with an egg and ají dip. ‘Already twenty-one? You need a wife.’

The Inca stone path branched up from the road and took a characteristically frontal approach to the pass. It was a stunning path, as good as any I’d followed in the Vilcabamba, stone-laid, purposeful and heading directly up between the rock-teeth towards the skyline – and it gave me heart to be following in the footsteps of the Incas again. The villagers below had told me that few people, if any, ever passed along the old road. At the top was a small apacheta, a cairn, which travellers had added stones to: a custom that the Incas were already following before the Spanish arrived. It seemed the instinct both to show that you have been and to guide those who are coming behind was a universal one from the Himalayas to the Atlas to the Andes.

From the pass at 15,000 feet the path fell away towards the jungle areas, the Yungas, and looking down made me think about the dynamics of the Inca Empire. It was not for nothing that so many of their great roads were in areas like these on the fringes of the Andes, where they dropped to the Amazon. This was where the trade and agricultural dynamic was at its most intense – what the academics liked to call the principle of ‘verticality’.

Climatic conditions can be very harsh in these areas – just after I was there an exceptionally bad drought wiped out half the potato harvest. However, such a period of hardship would not necessarily affect each altitude in quite the same way. While the fields of the puna might experience a drought, in the jungle they might be having a normal harvest. From the earliest times, the Andean peoples had adapted to this by keeping land at different levels precisely so as to be able to ride out these climatic variations. Many campesinos of the area still worked the system in which they cultivated land at high altitude, where they could grow potato and quinoa, but also had holdings in the nearby lowlands where they could grow maize or coca.

The same principle applied on a larger scale with trade: the peoples of the jungle and of the highlands needed each other’s produce (and not just for subsistence: the jungles could provide splendid feathers for decoration, the highlands woven wool from the alpaca and the llama). Paths like the one I was travelling on were a necessary part of the Inca drive to weave together the peoples of the area in a mutually beneficial exchange of goods.

Not far over the pass there was an old mining shaft near a lake where I could shelter for a while, with snow at the entrance and the Cerro Mururata framed beyond. Below was a small highland farming community, the village of Takesi, which had given this path its name. At 12,500 feet, it was a good height for farming potatoes, while the villagers had pasturage higher up for their llamas. The adobe huts of the village blended so perfectly with the surrounding landscape that I almost stumbled into it without realising.

There was enough evening sun to have a bathe in a rock-pool in the Rio Takesi that passed nearby, and the next day I descended even further down: the path was a supremely intelligent one, roller-coasting down the gradients and letting the miles drop away under my boots. I felt terrific – sun on my face, downhill all the way and even the pack started to feel lighter. It was the first time I had walked on my own in the Andes, and it was liberating.

The mining village of Chojlla, where the trail ended, pulled me up short – a brutal place, with shanty huts all around. It was dusk when I arrived and Radio Yungas was blaring from all the shacks, so that I could hear the same disc jockey’s voice as I walked along the line of huts. He was making a memorial announcement for someone who had died at precisely the same time the previous year. The faces that looked out at me were the most indifferent I had ever met in the Andes, unable even to reply to my greeting or do more than stare, telluric in the way the cold had carved raw cheekbones out of their mottled skin.

There was nowhere to stay, and precious little to eat, but a grumpy school caretaker let me sleep on one of the school desks, and I laid out my belongings on another as the floor was infested by cockroaches. My last oranges I lined up along the rail below the blackboard where the chalk went. There were old posters pinned up on the wall, exhorting the children of Bolivia to love the patria, the ‘fatherland’, to be honest, to learn how to tell the time and not to leave chewing-gum on their seats.

The windows of the school-room were broken and open, and I woke before first light, determined to leave as soon as possible. The only bus had been sold out days before, but there was a truck driver leaving who was selling standing-room only in his pick-up (at the same price as the bus, but no one could afford to argue with him). He kept us waiting for an hour as he loaded as many people and as much produce as possible into the pickup: I wedged my pack upright against the press of pigs and sacks of potatoes spilling around me.

The light was blue and I was cold. I could only just make out the faces of some of my fellow passengers, huddled into their shawls. Some of the women were swaying on their feet, and held small children against them. The smell of old clothing and of pig was overpowering, and around the truck-stop was another strange, sickly smell like regurgitated fruit, rotting and dying. But as I stood wedged against the side of the truck, the cold burning against my face, I felt a strong affection for the people around me. It was impossible not to feel their stoicism, the capacity of the Andean Indian to endure punishment, and it was impossible too not to feel angry at the punishment they were still being given.

One passenger was better dressed than the rest. He had gold teeth and a small leather bag which he held tightly to his chest. He noticed me looking at him and we fell into a desultory conversation. He was an engineer and told me that there were plenty of gringos like myself who got interested in mining. After letting this sink in, he came up very close and whispered in my ear, ‘I could sell you a small gold-mine, if you like.’ The sun was not yet up, and I was being sold a gold-mine.

Finally the truck took off into a swirl of continuous dust from the road and we were coated in it, the women pulling their shawls around themselves. I saw the sun come up over the jungle of Yungas, burning its way through the dust and the opalescent green before the truck finally dropped me at a crossroads in the middle of nowhere and a shack-owner offered to sell me a beer.

‘It’s too early to drink,’ I told him.

‘What do you mean, too early? It’s already ten o’clock.’

He was right. I had the beer and felt better for it.

*

A few days later and after some tough travelling by roads that bounced over the mountains, I was standing in yet another empty Bolivian street. The only difference was that this was the village of Tiahuanaco and nearby were the ruins I most wanted to see in Bolivia.