OLLANTAYTAMBO

COMING BACK INTO CUZCO BUS STATION first thing in the morning after a night on the coach had a nightmarish quality. I’d come thousands of miles and was dirty, tired and lugging a heavy pack past a notorious training ground for pickpockets. I had no money left to buy myself a moment of luxury, yet wasn’t sure where I was going to stay. And half my insides felt like they were hanging out.

‘Hey mister, why you got holes in your trousers? Your cojones will start to show,’ said one of the local guys leaning up against a wall. His friends leant forward. The market ladies laughed raucously. Like coyotes sensing weakness, I was quickly surrounded by what seemed to be every con-artist in Cuzco. ‘Hey mister, want a hotel?’ ‘Wanna good cambio for your dollars?’ ‘Taxi, taxi!’ One of the registered deaf and dumb beggars chose this inopportune moment to press a card stating his case on me. I was supposed to read it and then he would return and accept a donation. Some blond Mormon missionaries were standing by impassively, watching in pale suits and ties. They looked like they were part of a completely different movie.

Then out of the mêlée of voices I heard someone calling for passengers to ‘El Valle Sagrado’, the Sacred Valley. I had one of those moments that travellers sometimes need where you instinctively just let go. There was no need to spend more time in Cuzco, so why not head straight out again? The Sacred Valley bus would take me to the great site of Ollantaytambo, which I had never seen and which played a key role in the last days of the Incas. I heaved my pack up onto the roof to be strapped down and was away, with some relief.

By contrast to Cuzco, the arrival at Ollantaytambo was one of the best welcomes to a town I’ve ever had. The local bus I’d taken turned out to be full of weekenders and we’d stopped in the little town of Urubamba to eat at a small quinta called Los Geranios. Urubamba had a reputation for being a bit of a tourist town with some large government resort hotels, but this quinta was the real thing, a sun-filled courtyard with criolla music drifting around and huge plates of beans and chicharrones, deep-fried chunks of pork rib. There was a wedding party in full swing off to one side and the band were pumping it out. After a couple of Cristal beers I was well away, dancing with the bridesmaids and a pretty college girl from Lima who was visiting her relatives. The cares of the road fell from me.

By night-time, the band were playing one of my all-time favourites, the lament of ‘Mi Guajirita’, in which the singer implores his love to ‘Quiereme, quiereme, más’ (‘Love me, love me even more’), with a mournful tone that seemed uncertain where it was all going to end. My bus had long gone without me and two truck-drivers offered me a lift to Ollantaytambo in their large pick-up. As they’d drunk at least as much as I had, it was an unsteady journey along the rest of the valley, but with a full moon and a clear night I could see the imposing silhouette of Mt Veronica ahead as I stood on the back of the pick-up and let the wind hit me in the face. I was serenading the drivers with my own versions of Elvis songs and, during an impassioned rendition of ‘Good Rocking Tonite’, my hat blew off. The truckers were becoming almost incontinent with laughter and screeched unsteadily to a halt in the ditch.

With the assistant, Justo, I went back to look for the hat. We scrabbled around half in and out of the ditch looking for it, with trucks looming out of the night and blaring their horns in characteristic Andean style. As we walked back Justo turned to me and said, ‘Look at the mountain. Look at Veronica. Este es un momenta nítido’, using a word I’d only ever seen in literature and meaning that this was a moment of intense clarity. It was one of Borges’ favourite adjectives, which he used when describing events of hallucinatory sharpness in his mythologies. I looked again at Veronica, a cone of a mountain that looked like a Japanese wood-cut, such was the neatness of its silhouette.

They dropped me by the square and I swayed down the path to the little railway station and the river. I knew that there was a small albergue nearby, a hostel where members of the Cusichaca project would sometimes stay. A dog barked as I pushed the gate open into total darkness. A woman with long black hair appeared and seemed unfazed by receiving a drunken hiker in the middle of the night. Wendy lit a candle and showed me into a room. ‘I’m sorry it’s dark, there was a power-cut earlier. In fact, why am I doing this? We have the electricity back on now,’ and she flicked a switch to show a room totally unlike any I’d seen in Peru, with a bed fashioned out of the bare rock and simple tapestries hanging on the whitewashed walls. The baño (which I badly needed) was nearby, a toilet set over an off-shoot from the stream, with the white porcelain gleaming over the pitch black of the waters. You could hear the current swirling below as you sat on the can, a disconcertingly fluid experience which my bowels were mirroring.

Wendy and her partner Robert Randall had come to Peru at the end of the sixties and, together with some other friends, had set up a little bit of Woodstock in the middle of the Andes. The albergue, with its simple frontier-style buildings and, I discovered the next day, a sauna off to one side, had been built by them: they were activists in the local community, helping both with the school and with campaigns to preserve the village’s heritage. Robert had studied Quechua and led trips to obscure parts of the area, while Wendy knew much about the weaving techniques of the high villages. The place was full of the closely woven dark-red cochineal cloth associated with Chincheros and the pieces had the patina of age and hand-weaving.

Ollantaytambo was a good place to come not just because it had a lower altitude and mellower climate than Cuzco (and some magnificent ruins), but also because it marked the beginning of the final Inca retreat into the hills of the Vilcabamba and the subsequent deaths of the last Emperors. It was this route I now wanted to follow, out of conflicting emotions of piety, curiosity and completism: I wanted to see the story through to the end.

In the late afternoon I climbed up Ollantaytambo’s impressively fortified buildings. After losing Cuzco to the Spanish at the great battle of Sacsahuaman, Manco Inca had brought his troops here. From the top of the fort, one could see why it was the natural place for him to come.

Ollantaytambo had a dominating geographical position, being on the edge of the Urubamba plateau where the river began to channel down to the narrow gorges that curled around Machu Picchu and all the sites I had travelled to earlier. But the site also gave access to the north-west and the Vilcabamba over some high passes behind the town, giving Manco a good escape route if he needed it.

The tourist coaches that sometimes passed through Ollantaytambo for a cursory ten-minute stop on the way back from Machu Picchu had all left and I had the place almost to myself. Over the steep crags that fell away to the west, I could see a solitary goatherd in a baseball cap trying to round up his herd, as the sun set behind him.

I was high above the town. From the top of the ruins there was a peculiar acoustic effect. The bowl of the valley made the tiniest sound below reverberate: a child’s laugh from somewhere down by the river, echoed by another child; the hooting of the up-train as it made its way back to Cuzco; the thwack of feet hitting leather as a football was kicked around by the off-duty staff at the small bull-ring directly below me.

I noticed a funeral procession starting up from the small church in the square at the bottom of the hill. Half the town seemed to be following the coffin and the brass band that accompanied it. The music seemed effortlessly to transpose the melancholy of the Andean flute to the Western instruments, with a trumpet that floated the sadness up to me.

An early traveller in the nineteenth century had described the chants he had heard the Quechuan Indians making at such a funeral: ‘Why have you abandoned us? What have we done for you to leave us like this? Will we not see you again? ¿No beberas ya la chicha con la familia? will you no longer drink chicha with your family?’

From the top of the ruins I watched as the procession wove its way through the grids of the tight chequer-board pattern the town had retained since the time of the Incas. The funeral was for a Señora Juana, who I later discovered had lived down by the bridge across the river all her life. Again the acoustic was so clear that I could hear the mourners’ voices rising along with the brass band.

It must have been extraordinary for the Indians on that day in 1536 when the Spanish followed Manco here in an attempt to put the native rebellion down. The leader of the Spanish party was Hernando Pizarro, Franciso’s brother and ‘the evil genius’ of the Conquest, according to the historian William Prescott, whose ‘ambition and avarice were insatiable’, even in a group of men where such attributes were commonplace.

The conquistadores approached across the river-plain at early morning, and the Quechuans from their defences on high would have heard the amplified sound of the horses and the guttural swearing of the Spanish as they fired off the odd arquebus, more for effect than anything else as the range would have been insufficient.

However, no amount of bravado could quite disguise the Spaniards’ dismay at first seeing how impressive the defensive position of Ollantaytambo was (bizarrely, none of them had ever seen it before, although only a day’s journey from Cuzco) and the strength of forces that Manco had accumulated. A series of stepped terraces, built with the usual Inca flair for a steep slope, led up to the fortifications that clung to a knife-edge ridge. The only possible approach was at an angle that could leave a fit hiker breathless, let alone anyone trying to ride up on a horse, even in the light armour that the conquistadors had taken to wearing in Peru.

The Spanish would have seen rows of soldiers on every terrace stretching away above them, including many of the ferocious jungle tribes whose precision as archers was much feared by both Spanish and Indians alike. And at the top Manco Inca himself would have been riding up and down on a horse he had captured, showing himself defiantly to the Spanish enemy and rallying his own troops.

This was certainly in character. Manco Inca is the sometimes forgotten hero of Inca history. His predecessor Atahualpa is remembered as the Emperor whom Pizarro and his men first seized and ransomed for his weight in gold and silver before executing him, while the name of Tupac Amaru, the very last Inca, lives on for its symbolic value and has been sporadically revived as the focus for later resistance groups. But Manco was a more admirable character than either of them. At the time of this engagement at Ollantaytambo, he had survived both a brutal civil war and the Spanish Conquest, which along with a smallpox epidemic had managed to lay waste one of the world’s great empires in less than ten years. The world he had known had crumbled around him. Out of the ashes, and with some consummate political manoeuvring, he somehow managed to rally a rebellion which, if not ultimately successful, at least gave heart to his people.

Manco had been born a full (i.e. legitimate) son of Huayna Capac. After Huayna’s death, Manco backed Huascar in the disastrous civil wars between his brothers and so suffered for being on the losing side against Atahualpa. When there were subsequent reports of strange bearded men arriving on the coast, who seized and killed Atahualpa, Manco and the surviving followers of Huascar at first thought this was divine retribution on the usurper and welcomed the conquistadors on their arrival in Cuzco.

Indeed, so pleased was Manco with the Spanish for having killed Atahualpa that he voluntarily surrendered himself on the outskirts of Cuzco. Francisco Pizarro was very taken by this young prince who was so quick to do the Spaniards’ bidding. Needing a suitable puppet Inca to install on the throne, he chose Manco from the range of available brothers. For some years this worked satisfactorily, if uneasily, with Manco manoeuvring through the complicated net of Inca alliances left after the civil war. Many of Atahualpa’s old troops were still stationed in Cuzco, and some of his surviving brothers did not take kindly to Manco’s succession. But then, disillusioned by Spanish brutalities, he rebelled, took Sacsahuaman and nearly destroyed the Spanish in Cuzco.

Despite having been driven from Cuzco after the fall of Sacsahuaman, Manco still presented a formidable threat when he came to Ollantaytambo, and he had carefully forged alliances with many of the wild jungle tribes to the east, the Antisuyo quarter of the old Empire. He also had an effective plan. Manco used the town’s impressive system of channelled waterways to advantage. On a pre-arranged signal, just at the moment when the Spanish stopped in dismay in front of the great walls above them, water was released to flood the plain below. At the same time archers attached from either side. It was only with luck, as so often with the conquistadors, that they managed to ford the now swollen river and escape.

Still, it must have been wonderful for Manco and his troops to see their enemy retreating both humiliated and wet. That night there would have been much chicha drinking in the square. Even the Spaniards, no mean drinkers themselves, were always impressed by the prodigious capacity of the Incas to consume alcohol. At Manco’s own coronation earlier in Cuzco, the drains of the city were reported to have run continuously with the urine of the revellers, so bacchanalian was the consumption. I’ve since seen Quechuan muleteers put away enough sugar-cane spirit or rough aguardiente after pay-day to be medically anaesthetised, yet still manage to get home, if unsteadily. However, as Prescott mournfully remarks in his history, ‘This was the last triumph of the Inca.’

The following year the Spanish returned in larger numbers. Manco had lost many of his followers, who were taking the usual campaign sabbatical to return home for the harvest. The Spanish had caught a group of jungle archers out in the open and massacred them, although not before the archers had wounded many of their horses. Realising the hopelessness of his position, Manco decided to withdraw. He is reported to have given a speech worthy of Bonnie Prince Charlie’s departure from the Highlands. He told his followers that ‘he felt compelled to give satisfaction to the Antis [the tribes of the jungle] who had so long desired to see him, and so would visit them for a few days,’ although all who heard him must have known that the Inca was abandoning the homeland of the Cuzco plateau for ever.

The conquistadors had been lucky, but they had also brought their own luck. Time after time in the annals of the Conquest, one comes across moments when the occasional fatalistic impulse of the Incas led to their worst moments. Why did Atahualpa’s main commander Chalcuchima meekly and voluntarily surrender himself to the Spanish on their arrival when he could easily have annihilated them, 35,000 men against a handful? Why did the Quechuans allow the Spanish to make the fearsome ascent of the Royal Road from the coast to Cuzco without picking them off as they exhausted themselves on the high passes? Why had Manco himself fatally hesitated at the siege of Cuzco and waited for yet more troop reinforcements to arrive, thus losing the momentum of surprise – a momentum the Spanish intuitively understood as being necessary for war and used so impressively when they took Sacsahuaman?

It is too easy to ascribe the conquistadors’ success purely to superior technology, as romantic sympathisers with the Inca cause are prone to do. Pizarro’s men were also outstandingly brave and determined, however greedy and brutal they may have been. They grabbed every chance offered to them with both broad hands. The Incas did not.

I thought of Conrad’s great line in ‘Heart of Darkness’ – that the strength of conquerors is ‘just an accident arising from the weakness of others’.

High above the main site of Ollantaytambo was a small ruin that faced the setting sun and the mountain fastnesses that Manco would have retreated into. There were some holes in the walls and the usual fantasy had arisen that these might have been used to secure prisoners before some sort of ritual sacrifice (Charlton Heston would have played the role of the captured white man to perfection). In the unlikely event of this having been true, the sacrificial victims would at least have had a superb view before their deaths: the platform faced due west towards the mountains beyond Machu Picchu. As I sat there quietly in the last of the sun, I wondered if the Incas’ positioning of their sites was as much for the aesthetic qualities of stone, so that it caught the most flattering light of the day, as for the reasons of ‘sacred geography’ that were often given.

Like Sacsahuaman, it was easy to forget that just because Ollantaytambo was used as a fort in an hour of need, it was not necessarily constructed as one. This was in fact another of Pachacuti’s great buildings and carried many of his trademarks: the insistence on the highest quality of stonework and of ornamentation, with a spectacular setting. It could have been used as much for religious reasons as military ones, and its purpose may also have been to impress the peoples of the valleys below, whom Pachacuti had recently conquered. There was a noticeably redundant defensive wall, built behind the site on what was anyway an impregnable flank, but which greatly added to the grandeur of the place. Ollantaytambo was ‘decoratively military’, like a Victorian mock-Gothic castle. Manco’s enforced use of it might be compared to Balmoral being pressed into service for a last-ditch defence of the realm if Hitler had invaded Britain.

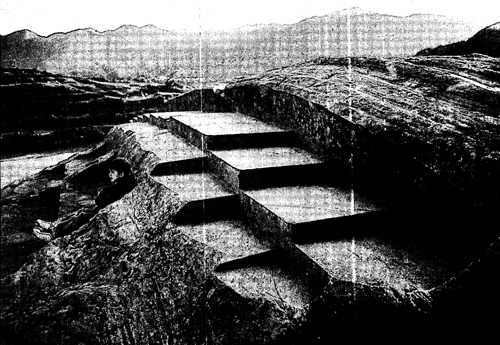

The most celebrated feature of Ollantaytambo were six stones. These great upright monoliths of pink porphyry were almost all that remained of the sun temple. They were arranged so as to face the rising sun, and had some of the strange bosses and protuberances that had so intrigued me elsewhere with Incaic stonework.

These stones revealed much of the Inca relationship and debt to conquered nations. Having now visited Tiahuanaco, I could see the clear connection between Ollantaytambo and that ancient site. There was the same distinctive Tiahuanacan stepped motif on one of the stones, and the Ollantaytambo masons had used thin strips of stone to joint the monoliths – a technique even more difficult than the usual dry-pointing and one which Señor Ribero had shown me at Tiahuanaco.

I had learnt from John Hemming some fascinating details relating to the building of Ollantaytambo. After the original inhabitants of the area had refused to submit peacefully to the Incas, Pachacuti had conquered them with a large army and burnt their town. He had then erected this magnificent memorial to Inca occupation which the Spanish had found so frightening and which modern tourists now admire. To do so, he had shipped in another client tribe from a different part of the Empire, the Colla near Tiahuanaco, whose burial towers I had seen at Sillustani. The Colla brought their stone-building techniques with them, if under duress: they must have suffered enormously in the transportation of the huge Ollantaytambo stones from the quarry across the valley. From records left by early Spanish chroniclers, who interviewed their descendants, we know that at one point they rebelled and fled back to modern-day Bolivia.

This certainly cast the building in a different light from ‘romantic Ollantaytambo’, described in such glowing terms by nineteenth-century travellers such as Charles Wiener and George Squier. Squier had even compared it to a ‘castle on the Rhine’. Yet this was a site built by an army of occupation, using forced slave labour who had been transplanted from their homelands to do so. Those sympathisers with the Inca cause, who picture a noble culture being decimated by the imperial West, sometimes forget that the Inca culture itself could be a cruel and colonising one.

*

I wandered down the hill and traced some of the waterways that still coursed around the town, some dividing the streets as they would originally have done in every Inca city and in Cuzco itself. The usual playfulness of Inca stonework was fully in evidence, particularly around the bases of the ruins themselves, where various fountains chased around corners and delightfully oblique carvings could appear if the rock was looked at hard enough. In a smaller way it echoed the ability at Machu Picchu to blend raw granite with cheeky curlicues of integrated sculpture – a niche here, some steps cut there.

In a rash moment I had revealed to Wendy at the hostel that I had occasionally done magic tricks for kids at parties, on a strictly amateur basis. One of her sons was having a fifth birthday the next day and she persuaded me against my better instincts to put on a show. I agreed before I realised quite how many friends young Nathan had. Standing behind my makeshift magician’s table, there was a sea of little Peruvian and American faces staring up at me expectantly, with an attendant phalanx of parents outnumbering their offspring.

It was a cheerful scene. A clown (a charming gay friend of Wendy’s) was wandering through the audience pouring water over people, to the children’s great amusement. Meanwhile the adults, the men with their beards and ponchos and the women in hippy dresses, looked like a festival audience after a mellow afternoon’s spliff-taking. I warmed them up by taking a few chocolates out of children’s ears, did some tricks with a balloon and the usual card-sharping stuff. It was time for the pièce de résistance. I borrowed a bowler hat from one of the Quechua women watching and then (with an impressive sweep of a cloak, the inappropriate spell of ‘Hey Geronimo’ and my own slight surprise at pulling it off) managed to produce a white dove out of the empty hat, which flew up startled into a completely blue sky. The audience of five-year-olds were so surprised by this that they sat there with open mouths. It was, to use Justo’s phrase, ‘un momento nítido’.

What with the extremes of the Andean climate and my travels through the deserts of the coast, it had taken me a while to realise that it was now spring here. As I climbed up the other side of the valley from Ollantaytambo and the albergue, I noticed how green the valley of the Urubamba had become. The pisonay had flowered in magnificent and shameless scarlet and the strawberry season was imminent. Against the green of the fields, the red-and-black ponchos of the workers stood out in sharp relief. It was a cheating spring, an October spring.

I was walking up to see the old Inca quarries above the town. The quarries were themselves remarkable not so much for what stones were left (there were several partially finished blocks) but for the view back to the town: from above, in the sunlight, one could still make out the route the stonemasons must have used to transport the stones, a track ghosting across the crops in the fields to the bottom of a ramp leading up the side of the temple-fortress site.

Much energy had been expended on various crackpot theories about how the Incas managed to construct their extraordinary buildings. The question asked was how they managed first to cut the blocks and then transport them into place with such uncanny precision, given that they had no metal tools or wheels to do so.

Colonel Percy Fawcett, the overrated British explorer who had disappeared up the Amazon in mysterious circumstances in 1925, had first started this trend. Before doing a Lucan, he had reported as gospel fact the wild rumour that a sort of ‘jungle-juice’ was able to dissolve solid granite. For a public who were as credulous then as now about any form of jungle medicine and who were also inclined, illogically, to put great credence on the words of a man who had since disappeared, this started a long and continuing search for the plant concerned. Others speculated that the Incas, so obsessed with the sun, might in some way have learnt to use parabolic reflectors, so concentrating the sun’s beams enough to act as a laser through the stone.

A more prosaic and infinitely more likely solution had been demonstrated by the academic Jean-Pierre Protzen, who had actually taken the time to test his theories out on site. He had shown that it was perfectly possible to shape the blocks using simple hammer stones from the river that had been rounded by the current. With these he could achieve the smooth bevelling characteristic of good Inca masonry. It seemed equally possible to drag the blocks considerable distances, given the enormous amounts of manpower the Incas had at their disposal through the system of mita, or annual labour tribute, from the locals and from client tribes like the Colla.

Along the path the builders must have used were some great blocks that had simply been abandoned along the way. In a nice phrase, these were known as the piedras cansadas or the ‘tired stones’. One was sitting placidly in the middle of a cultivated field. No one knows when or why this happened: they may have been abandoned when the Colla left, or when Pachacuti died and the estates passed from royal interest, or in the smallpox epidemic of around 1527. In any event, I liked to imagine the moment when a foreman took a break: ‘OK guys, let’s take five. We’ll pick up from where we left off next week, once we get a bit more help on the case.’ Five hundred years later, the job was still waiting to be finished.

There was a trio of brown-skinned boys splashing around in the Urubamba, and I went in for a swim after the climb. ‘Swim’ was perhaps the wrong word as the current was too strong to do much more than push back against the water like a jacuzzi. But up to my neck in the surging water, and with the mountains of the west still touched by sun in the distance, it felt pretty good.

I had the same view as I waited for the train at the station. There were files of uniformed school-kids waiting in lines along the platform: they had just processed around the village to mark the tenth anniversary of the village school. I was gratified when some swarmed around and recognised me as ‘el mago’, ‘the magician’. They were all swinging lanterns at one another and the air was lit up as if by glow-worms. At one point the teacher led the girls to one side of the track to urinate in the normal Andean way, using their full skirts to preserve modesty as they squatted down in a long line beside the railway tracks. (It was quite possible to come across streams of urine in Cuzco streets from Andean ladies caught short on the way to market.)

I swung onto the train and it rattled away down the tracks way beyond Machu Picchu and on towards the mountains of the north-west. If all went well, I was going to follow Manco to his final retreat in the heart of the Vilcabamba.

*

To my delight, the train was full of old friends from the Cusichaca Project who were heading back there to pack up at the end of the season. They had a crate of beer and we drank cold Cristals standing by the open door to the foot-plate, with the phosphorescent waters of the Urubamba swirling away below in the night light. Each time the train turned from side to side on the tight valley corners, the articulated links would stretch and sway us violently from side to side.

They had news of Roddy, who was not at Cusichaca as I had expected but was right down in Quillabamba at the end of the railway line, in the jungle, and I determined to go straight down there to meet up with him.

The beer and the end-of-dig feeling loosened tongues. In the enclosed world of the Project, the volunteers had always tended to be reticent with any criticism, as the canvas was thin and there was a feeling that somehow any comments would always get back to Ann. One of the volunteers now told me a story which stuck in my memory. They had just been in Cuzco to deliver this year’s huge collection of pottery found at the Cusichaca sites to the INC (the Instituto Nacional de Cultura, the government department responsible for archaeological sites). In passing, they had looked into the room where the pottery from previous years was stored, in rows of cardboard boxes marked ‘78’, ‘79’, ‘80’, ‘81’, like so many vintages. Apparently the place smelt like an old potting shed and there was a general feeling that Ann was becoming the victim of her own success: the scale of the digging had produced such an amount of pot that it was becoming impossible to assimilate an avalanche of samples.

An added problem was the narrowness of the time-scale involved in dating the pottery: the difference between a classic and post-Inca pot was only a hundred years, which could pose problems in delineating clear changes of design. From my own brief observations, classical archaeology did seem to be a discipline that could grind to an uncertain halt under the momentum of its own scrupulous thoroughness. The work that Ann had done with the local community – the restoration of canal-systems along Incaic lines and a feeling of pride in the past achievements of their ancestors – seemed much more profitable, perhaps the face of archaeology in the future.

The inevitable tensions of a long dig had also surfaced and many had quarrelled with Ann or her lieutenants about arrangements – there was a rumour (or threat) that in future seasons they would get diggers from an American organisation called Earthwatch who would actually pay to come down and work on the Project, supplanting the current volunteers. Personally my sympathies were with Ann; trying to run a camp that size, for the fifth successive season, would have tested the patience of a saint, let alone an archaeologist.

Davina, the camp administrator, had been through a terrible time while I had been away: her father had died suddenly in England, from a riding accident; at the same time she had contracted severe hepatitis. Despite a rocky start, I had become fond of her, and I was not surprised to hear that she had borne these misfortunes with quiet bravery.

There was tragic news of Graham, the ex-army organiser who had been looking after all the arrangements at the camp. Driving back to Cuzco at the end of the season, he had been involved in a head-on collision and died instantly: the fifty-gallon oil drum he was carrying on the back seat flew forward and broke his neck. During that hot, long season at the camp, Graham had been the good-humoured butt of our endless jokes for his ‘Carry On Up The Andes’ approach to life and his way of adjusting the solar-powered showers with bits of string. It made me feel worse about his death.

The Cusichaca lot bundled off at Kilometre 88 and I carried on alone, heading down the Urubamba river, past Machu Picchu, past Santa Teresa where we’d always got off for our exploring trips and on towards the Vilcabamba.

Passing beneath Machu Picchu reminded me that I was back in the footsteps of the man who’d started me on this journey. Indeed, one of the many curiosities about Hiram Bingham’s discovery of Machu Picchu was how quickly he’d left it and carried on downriver, just as I was doing. In his own words, he ‘pushed on down the Urubamba asking for ruins, offering cash prizes for good ones and a double bonus for any that would fit the description of the Temple of the Sun’.

Bingham had good reason to press on down the Urubamba in 1911. A Peruvian academic called Carlos Romero had alerted him to the recent discovery of a remarkable manuscript: a report dictated by one of the rebel Incas, Titu Cusi (Manco’s son), in 1570 as he led his people in their final resistance to the Spanish. It was the only eyewitness account of the Conquest by any of the major protagonists, Spanish or Quechuan, to have survived, which made it unusual enough. But to Bingham’s intense interest, Titu Cusi had dictated it for the King of Spain’s benefit from a city he called ‘Vilcabamba’.

The term ‘Vilcabamba’ was confusingly used for both an area and a city. The whole area of Vilcabamba was the last redoubt of the Inca defence against the Spanish, as was already well known by Bingham’s time, and the area is still known by the same name after the river that runs through it. It extended over several valleys to the north-west of Cuzco, between the rivers Urubamba and Apurímac, in the quarter of the Empire the Incas called Antisuyo, and was centred on a mountain site called Vitcos, near the White Rock of Chuquipaha.

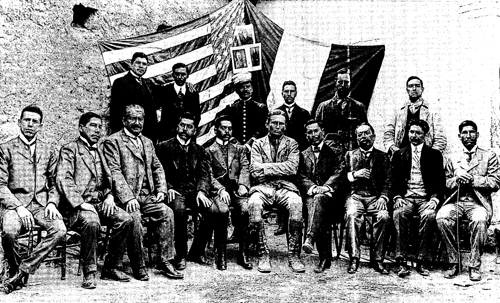

Hiram Bingham, seated at centre right of group, at the end of his successful 1911 expedition.

Hiram Bingham in characteristic pose (and boots): ‘His energy propelled him through the Urubamba in a rolling maul of enthusiasm and sheer drive.’

Martín Chambi: self-portrait, 1930: ‘the very essence of the photographer as lone explorer.’

Martín Chambi Autoretrato con Autoretrato (Self-portrait with self-portrait), 1923.

Martín Chambi Party-goers in the 1920s. ‘Cuzco se desalumbró, Cuzco woke up.’

Martín Chambi Juicio Oral, Corte Superior (Judgement in the High Court, Cuzco), 1928

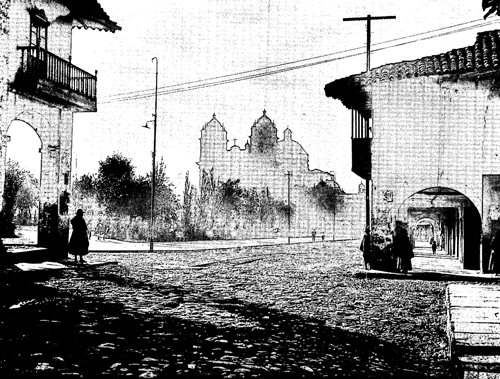

‘Martín Chambi was a chronicler of Cuzco for the remainder of his long life.’: early dawn at the Plaza dc Armas 1925;

Cuzco after thc earthquake in 1950, with Incaic walls visible beneath the colonial structure.

The carved steps of the Throne of the Inca on Rodadero hill above Cuzco, with Sacsahuaman beyond.

The Coricancha, or Sun Temple, in Cuzco after its post-earthquake restoration. ‘Nestled incongruously within the cloisters of a Spanish convent, the effect is like one of those odd medieval dishes, where an entire pigeon is roasted inside a pig’s head.’

Martín Chambi: Carved huacas at Sahuite. ‘The Incas worked stone with more facility than they did clay.’

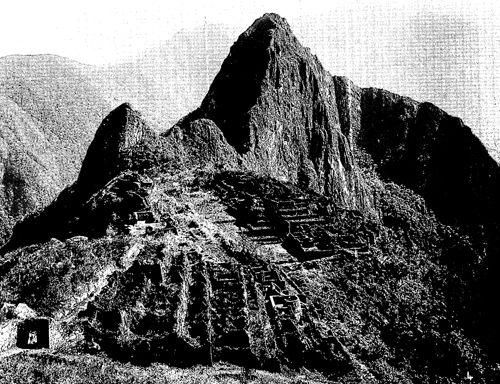

Martín Chambi’s picture of Machu Picchu in 1925; he frequently led expeditions to the ruins.

The Funerary Rock at Machu Picchu.

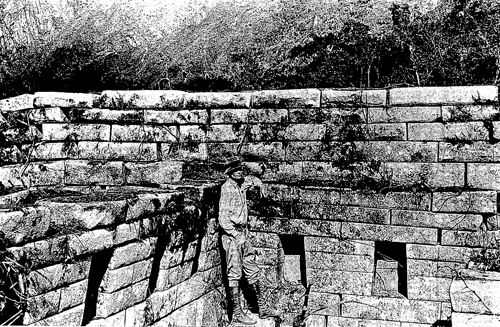

The so-called ‘Incahuatana’ (hitching-place of the Inca) above the main site at Ollantaytambo: ‘a small ruin that faced the setting sun and the mountain fastnesses that Manco would have retreated into.’

The carved stone of Qenko above Cuzco.

This was the area into which Manco led his people after leaving Ollantaytambo (referred to by Prescott as ‘an obscure fastness in the depths of the Andes’), and as a rump kingdom it long survived attempts by the Spanish to destroy it. However, in case even this proved vulnerable to persistent Spanish attack, the Incas decided on a last place of retreat, down towards the Amazon where they could lose themselves in the jungle. There they built the actual city of Vilcabamba, from which Titu Cusi dictated his memoirs, and which, confusingly, was not in the area of Vilcabamba. (To avoid such confusion, I have followed the convention of referring to the city throughout as ‘Old Vilcabamba’.)

Manco’s choice of the Vilcabamba area as a retreat from the Spanish was an inspired one. It was to be a full forty years after the Spanish Conquest and Atahualpa’s murder before the last Inca, Tupac Amaru, was finally caught and brought out of the mountains, to be publicly executed in Cuzco in 1572.

This gave time for a genealogy of Inca Emperors to flourish in Vilcabamba as pretenders over the mountains. Manco Inca was succeeded by his sons Sayri Tupac, Titu Cusi and Tupac Amaru, and it was Titu Cusi who dictated the remarkable document that had only been rediscovered shortly before Bingham’s arrival. In it the Inca told the life of his father Manco and gave a full account of what it was like to be on the receiving end of the Conquest, a useful corrective to the many European versions. Importantly, he also gave many new details as to the actual location of the city, Old Vilcabamba, in which he was living and which the Incas had made their base. From these details it was clear to Carlos Romero that a mistake had been made.

For the previous two centuries, all explorers to the region – the Comte de Sartiges, the geographer Raimondi, the traveller Charles Wiener – had assumed that Choquequirao must have been the great final city of the Incas, Old Vilcabamba. They were swayed to this judgement by Choquequirao’s magnificent position, the fact that no other major Inca sites were known of and, in Sartiges’ case, doubtless by the very human fact that he himself had managed to get there. But from Titu Cusi’s description, Romero was able to assert categorically that Choquequirao could not be Old Vilcabamba. It was, apart from anything else, too high.

Spurred on by the Titu Cusi manuscript, Romero, a dedicated scholar who deserves more recognition for his part in the Machu Picchu discovery, also re-examined the long account left by Father de la Calancha, an Augustinian monk, who had given many details about Old Vilcabamba in an epic account of the doings of his fellowship in Peru.

Romero published his findings in 1909, the year Bingham first arrived in Peru. Bingham’s timing, as always, was almost beyond luck, yet few men would have been so opportunistic and daring as to act quite as decisively on such information as he did. Romero reported from his reading of Titu Cusi that Old Vilcabamba lay at a low altitude, that it enjoyed the fruits of the forest, and he named various places near it which were a long way from Choquequirao. So when Bingham careered on down the Urubamba, he had that most intoxicating of documents figuratively under his arm, in Long John Silver style: a manuscript, which few others knew about, with good clues as to the whereabouts of an archaeological treasure. The Titu Cusi manuscript could show him the way and Carlos Romero had supplied some other detailed and scholarly pointers as to where to look for Old Vilcabamba, which, as Bingham constantly reminded his readers, was the real ‘lost city of the Incas’.

The search for Old Vilcabamba became his great obsession. One reason why he pressed on from Machu Picchu with such indecent haste after first discovering it must have been his quick realisation that however wonderful, Machu Picchu, like Choquequirao, did not fit particularly well with Titu Cusi’s account of the city of Old Vilcabamba. It was too high and also too close to Cuzco to offer any real escape from the relentlessly following conquistadors.

So Bingham left his colleagues behind to clear and map the Machu Picchu site (like many an explorer, he preferred the excitement of the search to the cleaning up) and pressed on down the valley in search of this city of Old Vilcabamba, accompanied only by the delightfully named Professor Harry Foote, who sounds like a character from Conan Doyle’s The Lost World or Spielberg’s Jurassic Park.

Bingham made the journey on foot and with mules. I felt no shame about sitting in a comfortable train to do the same, particularly as the food vendors kept jumping on at each stop: I filled up on coffee, cakes, tamales and chocolate (the best of the local varieties of chocolate bar was called ‘Sublime’, pronounced with three stressed syllables like ‘cor-blimey’).

As we left Santa Teresa and started to descend, the Urubamba widened into what felt like a major river, with wide pebbled shores that made it look coastal in the moonlight. The climate quickly changed from the brisk chill of an Andean night to a jungle moistness, and all the passengers started to disrobe. I watched with some fascination as an old Quechuan woman unwrapped herself like a mummy, each succeeding layer revealing more foodstuffs tucked about her person. By the time we got to Quillabamba, the vendors were getting on in shorts. One cheerful woman flashed a smile full of gold teeth as she waved papaya slices at the carriage.

Roddy was sitting morosely in Quillabamba’s only hostel when I found him. A few days of Quillabamba’s delights had clearly exhausted him. It was good to see him again. We headed out for a meal, passing a hairdresser’s nearby called the ‘Peluquería Beatles’, with photos of the ‘Fab Four’ in the window in their early-sixties ‘Beatles cut’ days: it was a style that many of the Indians in Quillabamba still followed. Next to it was a stationer’s with an array of comics outside: Roddy pointed out to me some of the more lurid titles such as El Sadismo and La Ninfomanía, illustrated in photo-romance style with caption-bubbles coming from the characters’ heads; they were from a series called Psicológico Trauma (Psychological Trauma), with equally lurid covers, and sat oddly with the children’s notebooks and sets of pencils.

For a town with a wild reputation, Quillabamba seemed quite stately. There were wide streets and a large market, to which vendors would come from hundreds of miles around. Yet this was a place that back in the 1960s and 70s had been on the frontier. The state in which it lay, La Convención, was then a byword for terrorist activity, and the guerrilla Hugo Blanco (later, like all good guerrillas, to become a senator) had led his men in fierce resistance to central government. Gunmen were regularly seen on the streets. In those days, it was not a good place to be in if you were a government official and we had heard that those days were returning with the Sendero Luminoso, the ‘Shining Path’ movement.

It was also a bad place to be a chicken. I had never seen so much chicken being fried. Every sidewalk, bar and restaurant seemed to have a rotating spit of birds. The standard dish, to go, was a quarter of chicken, chips and a beer. As they ate this, the citizens would perambulate around the square on a gentle paseo, taking in the evening air and the other chicken eaters.

There were little bars set up in the open doing a brisk business. Each stall had a TV attached, blatantly hitched up to an illegal feed from the mains cable above. In a scene reminiscent of the recently released Bladerunner, the bar-women were cooking and serving food in a cloud of smoke: a cluster of clients around them were watching mesmerised as poorly receiving televisions played video hits from Europe and the States. We ordered a bottle of rum and washed down some lomos americanos (steaks with banana, eggs, chips and cheese), as Rod Stewart sang ‘Maggie May’ on the screen. It was difficult to know what the average Peruvian would make of lines like ‘All you did was wreck my bed / and in the morning kick me in the head’, although they were not that far from some of the criolla ballads about ‘la negra’, who did her man wrong.

A vendor came by with a fabulous array of jungle ice-creams: mango, tangerine, coconut, even avocado. The best (Roddy had done extensive pre-sampling) was lúcuma, eggfruit. As we sat eating ice-cream, an old Scotsman seized on us as the first Europeans he’d seen for five years. He had been living in the jungle prospecting for gold and looked it, wearing a battered check shirt and some thin Peruvian tracksuit bottoms with elasticated legs that cruelly showed the swellings and abrasions around his ankles. His stubbled face was pockmarked with sores and rashes. He came into Quillabamba occasionally when he got lucky to cash in his finds and buy some chicken and beer.

The Scotsman told us dolefully that the amount of metal he was ‘taking’ was diminishing each year. ‘Heard of any rich spots?’ he asked hopefully, and refused to believe that we hadn’t, or our protestations that we weren’t there looking for gold. ‘Why else come to Quillabamba?’ was his attitude.

He told us more about the Sendero Luminoso. Up until recently they had been a distant rumour, an impending storm, centred around Ayacucho in the south. Now they were building up strength in La Convención, particularly along the Apurimac, for the same reason that guerrillas since the time of Manco Inca had come here. It was ideal country to mount a campaign, with many inaccessible valleys both to hide in and launch sallies from. ‘These guys aren’t like the old terrorists,’ said our Scottish friend (we never learnt his name), with some regret. ‘The old ones would cut you a bit of slack, leave old-timers like me alone. But these guys …’ He made a gesture of a neck being cut.

We gave him more rum. ‘Have you heard of the cult of Fatima?’ he asked. We hadn’t. ‘Well, let me give you one piece of advice. Make sure, when you get back to Europe, that you investigate the cult of Fatima.’ And with that he hobbled off into the night.

Roddy took me off the next morning for a fortifying breakfast at a market stall he had discovered. The ladies greeted him like a regular prized customer, as well they might: Roddy had a prodigious breakfast appetite and I had once seen him eat six bananas on the trot within five minutes of awakening. Roddy ordered two jugos especiales for us, long fruit juices made up of orange, papaya and pineapple, mixed with lime juice and raw egg to give sabor and beer to give fuerza. The ingredients were solemnly prepared for us in one of the big Kenwood mixers that were such status symbols in the remote areas of Peru.

It seemed a good time to sell Roddy on my plan. My idea was that we should travel into the heart of the Vilcabamba, to Vitcos and the famous White Rock nearby. I’d already tried once to get a permit to do this, without success, as the government was worried about the growing Sendero Luminoso presence in the region. The only way we could do it was to travel without papers and risk getting caught by the police. After another jugo especial, Roddy was game for it, although such was the kick of the especiales that I could by then probably have got him to dance naked in the town square with a live chicken, if such a thing existed in Quillabamba.