ADENTRO (WITHIN)

IN A WAY I WAS BEHAVING like Fernando or Titus Groan – returning to see a place that I had once known well. But I was also going further, for I was determined to press on down into the jungle and finally see the city of Old Vilcabamba at Espiritu Pampa, the last city of the Incas, a magnet for every explorer in this part of the Andes since Hiram Bingham himself. It rankled that it had eluded me before, and there was something about the descriptions of this huge city down in the rainforest that seemed incomplete or that I had found (perhaps wilfully, to force myself to travel there) impossible to visualise.

I was still as ambivalent about the Amazon as I had been when I first experienced it in Ecuador. I decided to go and see a man who knew about the jungle. It had taken me years to discover where Nicholas Asheshov lived (the last address I had had for him was at the Lima Times). I knew his name well from tales of explorers in the sixties. When I did finally manage to track him down, it came as a surprise to discover that he now lived just down the road from Ollantaytambo, where he was running a hotel.

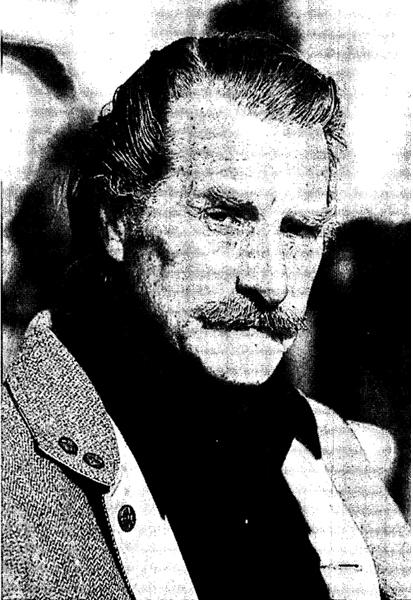

‘You’ll see me at the bar,’ Nicholas had said on the phone. ‘I’m a white-haired old buffer doddering about.’ In fact Asheshov, while about sixty and now partially sighted, was wearing a faded blue denim jacket and looked extremely fit. Later he told me that he deliberately dressed like a down-at-heel tourist in his own hotel so that no one would realise he was the manager and approach him with complaints about the service.

Nick had had a supremely adventurous life. As a young man in the fifties, he had come out to Peru (‘for all those gorgeous girls – it sounded the nearest thing to a cowboy film’) by working his passage on an oil-tanker and had then stayed to carve out a lively journalistic career with the Lima Times. This had given him the means and the excuse to travel through much of what Paddington Bear would have called ‘darkest Peru’. I knew that Asheshov had worked closely with such legendary explorers as Gene Savoy (indeed, he had often bailed Savoy out of jail) and had covered some of the small wars that occasionally erupted over the continent as a freelance for Fleet Street. He had also been responsible for the tabloid battle between the Mail and the Express that Ann Kendall had unwittingly found herself in (by his own admission, not perhaps his most glorious moment). Along the way, Asheshov had always made time for some supremely intrepid exploring.

It was a while before we circled around to talking about it, as we stood at the bar. Nick plied me with double whiskies (it was, after all, his bar) and told me he could still sail a thirty-foot yacht even though he had problems seeing which bottle of Scotch was which on the other side of the counter.

He noticed my clear curiosity about the hotel. ‘I made a lot of money on the markets down in Chile during the boom years of the early 90s – enough to buy this place, which up until then had been a lumbering government-run white elephant. Now we want to turn it into a total experience for the traveller. We’re going to call it Inca-Land.’ Some disused railway-tracks (from a long-abandoned plan to connect the hotel to Machu Picchu direct by train) ran right up to the bungalow house to one side, a house which Asheshov had converted from the original railway station. Cattle now grazed on the grass covering the disused track.

He reminded me of a character out of Conrad: the same bullish determination to carve a way in a still surprisingly open part of the world, mitigated by long experience of the problems in doing so. Asheshov’s father had been an émigré White Russian bacteriologist, his mother an English pathologist, and he had grown up in the West Country before getting the urge to travel himself. He had nine children, fathered over a thirty-year span – but he also had a nice line in self-deprecation which prevented any comparisons to Hemingway or the macho image which his record might suggest.

It was clear that Asheshov’s heart was more in exploring than in the hotel business – he had spent much time in the little-known areas to the north-west of the Vilcabamba, along the Apurimac. ‘The thing is, Peru’s so littered with ruins that there’s something seriously wrong if an area doesn’t have any – either no one’s looked hard enough or they’re just incompetent.’

Asheshov was, like most explorers, slightly contemptuous of archaeologists. ‘They’re trained to keep their noses to the ground, preferably below ground. So they rarely find the genuine lost cities out in the bush and frankly they don’t even go looking for them. It wouldn’t be scientific.’

‘I used to think, perhaps naively, that if you found a lost city and so could provide work for needy archaeologists, they might respect you for it, or at least buy you a drink. Not a bit of it. They hated Bingham and disliked Gene Savoy intensely. Both of them were accused formally of being huaqueros, grave-robbers. It’s unbelievable!’

In 1963 he had become involved in one of the strangest of all the expeditions to the Vilcabamba. Two Americans, Brooks Baekeland and Peter Gimbel, had decided that the only way to penetrate the higher interior plateau to the north-west was simply to parachute in. Using aeroplanes as a tool of exploration had already been extensively done – the Shippee-Johnson aerial expedition of 1931, for instance, had both mapped Chan-Chan by air and surveyed the Urubamba valley – but no one had ever parachuted into unknown territory before, at least not for a scientific and legitimate purpose. The area the Americans wanted to investigate through this radical plan was a large, intriguing plateau jutting right out into the Amazon basin like the prow of a ship, 9000 square miles of uninhabited land – a ‘Lost World’, as Asheshov described it.

Within seconds of arriving they realised why: ‘I was just thinking that this [the parachute landing] was even better than we had dreamed,’ wrote Baedeland later, ‘when I felt cold water seeping in through the knees of my jump suit.’ What looked like firm ground from the air was in fact a bog, and much of the plateau was similarly water-logged, making it totally unsuitable for human habitation, agriculture or indeed expeditions. In its exposed position, the plateau received the first drenching of water from the air flowing in over the Amazon basin.

The team were in real trouble. They had intended to make a bridgehead after their parachute drop and prepare an air-strip (Asheshov referred to it sarcastically as ‘Vilcabamba International’) so that further supplies could be brought and they themselves could at a later stage be flown out. To make the air-strip they had planned to drop a 700-pound bulldozer, which, even disassembled, was clearly not now a practical proposition. It looked as if they might have to walk out – a walk across completely uncharted territory, for hundreds of miles.

This was where Asheshov had come in. ‘I could see from the word go that they were probably a bunch of assholes,’ he said in his characteristically forthright way. ‘And Brooks fulfilled that early promise by turning out to be a total asshole.’ Not knowing the explorers myself, I refused to be drawn on this, although in the article they had subsequently written I had noticed a worrying tendency for them to say ‘Holy Smoke’ to each other, an expression I had otherwise only heard Batman use to Robin. There was also a terrific but equally worrying caption over a shot of the team wading through a mountain stream: ‘A false step on these slippery rocks could be a man’s last.’

Asheshov had been asked to find a way in to rescue them, although they themselves (and this was where Nick felt they had been such a liability) steadfastly refused to admit that they needed to be rescued. Nick went in with two local helpers (‘Policarpio, a Campa chief, and a backwoodsman called Angel Soto’) and tried to cut a way up the Pichari river, seemingly the only way through the high cliffs that surrounded the plateau from the Apurimac canyon. Initially he had with him a distinguished biologist, Hans Koepcke, but it was too much for the scientist and he turned back. (A few years later Koepcke’s seventeen-year-old daughter Juliana was the only passenger to emerge out of the jungle after a plane crash in the Pucallpa region – because of Asheshov’s connection with him, Koepcke allowed the journalist to get a front-page scoop on the story for the Daily Mail.)

The Pichari river proved a nightmarish mission from which Asheshov returned emaciated and exhausted – and without the American parachutists, who had refused to descend that way: he showed me a photo of himself hanging between the arms of his two Peruvian helpers, half his usual weight.

‘I forget how Brooks and Gimbel, on one side, and me on the other quarrelled, but it was all done by letter on my side, and by walkie-talkie to the pilots on theirs. From the Drop Zone I sent Brooks and Gimbel some notes and suggestions. These were picked up by hooks trailing from the planes and Poli, Angel and I set up half a dozen pick-ups and rescued all their expensive parachutes. My notes, whatever they said – they were probably insufferably cocky – went down like lead balloons and we were told “not to come and rescue them and to get out of the Vilcabamba!” – the pilots were even told not to continue to supply us.’

‘We headed off towards the Pongo, so as not to have to return down the Pichari, which actually had been pretty difficult, with dreadful thickets of cane, cliffs, waterfalls. We were wet, lost and hungry most of the time. Angel was at one point going along a very sharp ridge and almost fell off a precipice. He only saved himself by letting his baggage drop instead. I took it as a warning and decided to go back the way we’d come, which turned out to be as miserable as we thought it would be. I remember raiding our medicines for a few remaining cough drops because we were hungry. Poli managed to shoot some monkeys but they were so tough even after hours of smoking that I could only manage the heart, liver and kidneys.’

Meanwhile the American team above on the plateau were calmly doing the usual things expeditions like to put on their letterheads (‘we studied the local topography and fauna’). Brooks Baedeland asked for new sneakers to be dropped down to him at regular intervals. After telling Asheshov to head back without them, they set off in the other direction, north-east towards the Urubamba, thinking that in the more open country they would have more chance of receiving regular air-drops (this had been one of their concerns about returning with Asheshov). However, although not as precipitous as the Apurimac territory, their route soon became heavily wooded and, good as the pilots were (‘And they were very good,’ said Asheshov), they couldn’t make all the drops. ‘What’s more,’ said Nick, with only an understandable hint of irritation from a man who’d offered them a quicker way out, ‘instead of the fifteen days they thought this “shorter route” would take, it took sixty-one.’

By the time Baedeland and his team finally arrived at a Dominican mission on the Urubamba – ‘Sod’s law that you always emerge out of the jungle somewhere where you can’t even get a decent drink,’ commented Asheshov – they were nearly starved. They had also experienced close encounters with possibly hostile Indians (‘Though we felt we had been observed, we couldn’t be sure,’ wrote Baedeland in what must be the most common of all jungle literature devices), snakes that never materialised and the usual literary incidents of travel in the Vilcabamba, including at one point a stoic – and, it must be said, absurd – line from Baedeland about how ‘I thought I was going to die, but was not much concerned.’ They had not discovered a single stone that could have been placed there by a human hand, pre-Columbian man clearly having realised early on that the whole area was best left well alone.

The experience with the American team had, if anything, just whetted Asheshov’s appetite for more exploration. That was why he had been so interested when in 1970, now promoted to Features Editor at the Lima Times, he had been approached by one of his freelance writers, Robert Nichols, with a story about Paititi. Paititi was the name the Spanish conquistadors had given to a mythical ciudad perdida, a lost city of riches that was supposed to be as yet undiscovered in the jungle, an ancient legend that twentieth-century explorers had constantly ridiculed at the same time as they succumbed themselves to the same powerful myth.

‘Now I’d always said that there was about as much chance of finding Paititi or El Dorado as of winning the New York State lottery. But Bob was a very tough guy,’ said Nick, ‘and a man who really knew what he was talking about. He wasn’t a bullshitter. He’d spent years in the jungle on his own, writing stuff for me, and he’d travelled to some of the toughest places. If he said he’d come across something, then I believed him.’

Nichols showed Asheshov on the map where he was planning to go. ‘To be honest, it was a busy day in the office, press day, and I didn’t really concentrate too hard on precisely where he was heading. But later I remembered it was further down in the jungle from his old stomping ground of La Convención.’ La Convención was the area of Peru that I had done most of my own exploring in and it was where I had first heard Nichols’ name mentioned. ‘I just gathered that he was heading into the Alto Madre de Dios jungles at the bottom of the Q’osñipata valley. It’s still a tough place today but it was a really tough place back then in the sixties. I didn’t like to press him too hard for the details of precisely where he was going – it was his story and, as you know, explorers can get cagey about that kind of stuff.’

Asheshov paused and a waiter came to take him over to the table which was reserved for him every evening. The waiter read the menu out to us but it was obviously a formality. ‘I’ll have the set meal as usual, Jorge,’ said Asheshov before I could say anything, ‘and so will Señor Hugo here.’ Asheshov ate distractedly, hardly bothering about what was put in front of him. He was completely focusing on the events of thirty years before.

‘To be honest, it was only when Bob didn’t come back well over a month after he said he would that I started to get really concerned. Then more months passed. In the end, I headed down to the area myself.’

‘Some priests from the Dominican mission at Shintuya told me that they had seen Bob and that he’d headed into the jungle with a pair of wild young French travellers. They were worried that none of them had returned. What’s more, Bob had also set off with half a dozen Mashco Indians as guides. These guides had returned shortly afterwards. Apparently they had refused to go on past the Shinkikibeni petroglyphs. They said that Bob and the two Frenchmen had pressed on.’

More whiskies arrived at the table. ‘I hired a plane to fly over the area in search of any traces, and at the same time I got a land expedition to go on their trail, led by Elvin Berg.’ This was the same expert Peruvian guide who had explored with John Ridgway and who had later been savagely tortured and killed by the Sendero Luminoso in 1984. ‘Even with Elvin leading the team, they had no luck at all.’

‘This was 1970. We spent six more months looking with no success and no further indication of a Paititi. But two years later a quite young Japanese law student turned up out of nowhere and volunteered his help. He was very persistent. His name was Yoshiharu Sekino.’

Yoshiharu Sekino went into the jungle alone and eventually found what turned out to be the killers of Nichols and the two Frenchmen. It was an extraordinary achievement. From them and from other witnesses, Sekino pieced together the story of what must have happened to the explorers. This was the story as he had told it to Asheshov and as Asheshov now told it to me.

The two young Frenchmen (whom the missionaries had described to Asheshov as being volatile) had apparently made advances to the local Machiguenga women. ‘Nichols would have been horrified,’ said Asheshov. ‘Years of living in the jungle had made him very careful.’ Naturally this had not gone down well with the tribe. Relationships had quickly soured, leading to the murders of Nichols and his companions.

Yoshiharu Sekino had even been able to take a photo of the killers with Nichols’ machete and some of his surviving possessions. Asheshov knew that one of the killers was still alive today, almost thirty years later.

As for Paititi, Sekino went back more than once trying to follow up Nichols’ lead, armed with satellite photographs which did seem to show a curious series of ‘dots’, apparently in a neat triangular alignment. He found nothing. In the years that followed, Nichols’ disappearance fuelled further interest in the Paititi legend.

By now we were on the fifth double whisky. Asheshov looked at me with his disconcertingly clear blue, almost sightless eyes: ‘I still think a lot about Bob,’ he said. ‘The thing is, you see, he was stoned to death. It must have been a terrible way to die.’

*

At first the passengers in the bus out of Ollantaytambo were unsure about how to react when the young hustler in the Hawaiian shirt – a cholo of the streets if ever there was one – stood up and started to address them. These were mountain people, usually ‘muy recto y callado’ (‘very proper and reserved’), at least when sober, and they behaved much as a British train-carriage would when serenaded by a busker – by looking out of the window or exchanging amused glances of embarrassment. I was still nursing a vicious hangover from my evening with Nick Asheshov and had only slept for about four hours – but there was something about the hustler that commanded attention.

He was a good-looking young guy, with the darker skin and gold-capped teeth of the jungle towns and he brought a rush of vibrancy into the bus as we headed out of Ollantaytambo. His patter of ferocious and scatological Spanish came pouring out in a torrent as he began a series of magic tricks, standing in the aisle and swaying from the hips each time the bus took a corner on two wheels. ‘Look at these cards – here’s a Jack – you look a bit of a lad yourself, Sir’ – this to a man who in Britain would have been wearing a grey suit. ‘Now watch – I’m going to eat the card – and then this one too – and another – and now watch.’ With elaborate pantomime he produced the missing cards from between his buttocks, digested and excreted intact. The fat lady travelling with her husband, kids and assorted agricultural produce gave a huge roar of laughter and nudged her husband so hard in the ribs she could have cracked them. ‘Que cabrón! What a stud!’ she shouted.

Encouraged, the hustler began his own demographic survey of the passengers’ bathing habits. ‘Now, as we all know, the ladies are very particular about their soaps. Señora, what soap do you use?’

‘Camay.’

‘And you, Señora?’

‘Lux’ (pronounced ‘looks’).

‘What about you, Sir, what soap do you use?’ he asked a Señor in a battered straw hat who wasn’t paying much attention. The man shrugged. ‘¡Ya ven! See what I mean!’ screamed the Hawaiian-shirted one in triumph, ‘that’s the problem with men!’

By now he had the ladies in the palm of his hand, out of which he finessed some suspiciously sticky bars of nougat: ‘I’m going to give one of these to each of you sin compromiso [‘with no obligation’]. You can always hand them back later if you don’t want them. Otherwise they’re yours for just two soles.’

Then he had a last trick for us. Whipping a tube of vivid red lipstick out from his bum-bag, he gave a dab to his lips and flounced the Hawaiian shirt around his waist. ‘Do you think I’m a marica then, a maricón, a great big pansy?’ The woman he was asking screamed with laughter and embarrassment. ‘No, do you really?’ The woman paused. Whatever she said was going to make her the centre of attention. ‘No.’ ‘Then give me a kiss,’ and he smacked her on the lips to a roar of approval from the rest of the coach.

He paused, as if a thought had just occurred to him: ‘Momento. Those delicious bars I gave you. The only problem is – now that you’ve handled the products, they may be too shop-soiled to sell again. Maybe you won’t be able to give them back after all, so give me your money!’ In the laughter that followed, he must have picked up about forty soles in profit – twice what a muleteer could hope to earn in a day.

Through a burst of static on the driver’s radio came a fine Colombian rendition of ‘La Cosita’, ‘The Little Thing’, a salsa song about Wayne Bobbitt losing his penis (the said ‘little thing’), with the singer trying to inspire Wayne with a philosophical attitude (‘Why are you worrying, Wayne? … What you’ve lost is only a little thing … which can only lead to trouble for a man anyway’). The Bobbitt case had aroused considerable interest in South America, not least because his wife Lorena, who had done the Struwelpeter bit, was herself Ecuadorian.

We were beginning the long haul up the pass known as Málaga or Panticalla. Looming above us was the mountain of Veronica, or Wakay Willka, a perfect triangle of white above a patchwork of brown fields and thatched huts, each with its chacra or small-holding. It was still early morning (the bus had departed at dawn) and the early fires lit in some of the huts had left smoke seeping through every crack in the thatch, as if the whole building was smoking.

The very fact that there were alternative Spanish names here as well as Indian ones – the Malaga pass, Mt Veronica – in a mountain range of otherwise largely Quechuan peaks showed the importance of this area to the conquistadors. It marked the edge of their dominions: beyond lay the Inca rump kingdom of Vilcabamba that Manco Inca had established.

After Manco’s death in 1544 at the hands of the treacherous Spanish he had taken in as refugees, the state of Vilcabamba had passed to his sons. Under first Sayri Tupac and then Titu Cusi the Incas had continued to hold the Spanish off by astute diplomacy. They had frequently pretended to be about to ‘come out’ from their hideaway and accept the lands that a succession of Spanish viceroys offered as bribes (Sayri Tupac did actually emerge towards the end of his life, in 1560, but disappointed the Spanish by promptly dying).

Titu Cusi, a tougher character altogether than Sayri Tupac, had flirted constantly with the Spanish, receiving envoys and allowing Christian missionaries into the Vilcabamba. He liked to give the impression that he was on the verge of giving way to Spanish importunities, while never quite doing so. In this he was helped by the turnover in Spanish viceroys: given potential assassination, disease and political intrigue, it was a job with a short life expectancy and none gathered quite enough momentum to really address ‘the Inca problem’.

So by 1570 the state of Vilcabamba was still intact, some forty years after the Conquest. It had successfully preserved most of the Inca traditions, albeit in miniature and with limited resources.

My battered copy of Prescott’s nineteenth-century classic, History of the Conquest of Peru, was no longer any good to me. He had ended his account of the Conquest shortly after the time of Manco’s death and had shown little interest in the achievements of the very last Incas. However, one of John Hemming’s great contributions in The Conquest of the Incas, his twentieth-century reworking of Prescott, had been to tell the story of the forgotten final years of the Empire as it survived after Manco.

John Hemming’s reputation had grown enormously since I had first met him in the study of his house back in London. His book had been recognised as a towering work of scholarship which mined every available bit of source material to tell the detailed history. Back in Cuzco, Barry Walker’s voice had grown positively hushed as he told me that John had once sat in his bar, having a quiet pint with him. ‘Just over there,’ he said, pointing out the precise chair he had sat on. The Peruvian government had awarded him the Ordén de Mérito. They hadn’t yet got around to selling T-shirts in the Plaza de Armas saying ‘John Hemming is God’, but it was only a matter of time.

For his achievement in resurrecting the last days of the Vilcabamba Empire was two-fold: on the one hand it was simply a matter of putting the historical record straight – the broad outline of the story had always been known, but Hemming had filled out many details with contemporary sources and given it added legitimacy; perhaps more importantly, the book was also a resounding clarion call to a nation at times unsure of its own identity, for it was a reminder that the Incas did not go gently into that good night when the Spanish arrived (as the popular imagination supposed), but courageously fought a spirited rearguard action to preserve the essence of Quechuan culture – a culture which was now becoming increasingly viewed as Peru’s natural patrimony.

Hemming had not only revisited the sources to tell the story of how protracted the end-game had been after Manco’s death, but had also put forward an attractive picture of how Vilcabamba could possibly have continued indefinitely, ‘a native enclave related to Spanish Peru in much the same way as Lesotho or Swaziland were related to modern South Africa’.

Unfortunately a viceroy arrived who was not content with this status quo: Francisco de Toledo, unlike most of his more aristocratic predecessors, was essentially a civil servant of great efficiency and he wanted tidy solutions to the problems that had beset Peru since the Conquest and caused endless civil wars. A principal problem was the continued existence of an Inca stronghold and Toledo determined to flush the Incas out of their lair. He was helped in this by the sudden death of Titu Cusi (probably from excess drinking, although his subjects suspected poison and brutally murdered a nearby Christian priest in retaliation). In the transitional period before the establishment of his successor, yet another son of Manco’s called Tupac Amaru, the military commanders of Vilcabamba made misjudged decisions that Titu Cusi would never have done, needlessly killing some Spaniards and providing the sort of provocation that a legalist like Toledo could exploit to justify using force. So was to begin the agonising final invasion of Vilcabamba.

In April 1572, at the start of the dry season in the mountains, a party set off from Cuzco with a mission to destroy for ever the last vestiges of the Inca dynasty. Many of their old enemies joined the Spanish against them and took part in the expedition, including the Cañari tribe, one of the subject races the Inca Empire had treated with ferocity and who had been so ardent in their pursuit of Manco. There were also some members of Tupac Amaru’s own family, who had defected to the Spanish – these last were to prove some of the most relentless in pursuit of their own kin, as much to prove to the Spanish that they had no residual rebellious tendencies themselves.

As we headed up to the pass that led to Vilcabamba, I was travelling on the route the Spaniards took on that final journey to get rid of the Incas. It was a spectacular and tough journey even by bus, as the road was bad and the pass was at around 14,000 feet. For the Spanish advancing into hostile territory, it must have been daunting. When the French traveller Charles Wiener came this way in the nineteenth century, he had been startled to come across ‘un singulier monument’: a pyramid of the skulls of horses that had died on the ascent.

The members of the punitive expedition were a pretty ragged bunch. These were no longer the tough conquistadors and battle-hardened fighters of the original Conquest. Three of the four Pizarro brothers had since died, all violently. The last brother, Hernando, had been held for twenty years in a Spanish prison and was a broken old man. Most of their original companions had died from disease or civil war. Instead Viceroy Toledo had assembled the best force he could from the riff-raff of Cuzco, including the dandies and merchants who wanted to go along for the ride. While only too happy to dress up in armour and live out some of the romantic legends of adventurous conquest they had been brought up on, many of them were far from being soldiers.

With the party were just three of the original conquistadores, now old men, who could advise on how to deal with an Inca attack. One of them, Alonso de Mesa, had been a bit of a lad in his youth, fathering six children by six different wives and a further child by a concubine. The early camp-fire talk as they set out from Cuzco would have tried to re-live the stories of derring-do and adventure from forty years before, doubtless much glossed over to ignore the slaughter of helpless Indians and exaggerate the chivalric prowess of the conquistadores.

The stories would have been of how Pizarro (or the Marquis, as he had latterly become) and his knights had been so few against so many, and yet prevailed. These tales – much embroidered – would have been part of the armoury that accompanied Toledo’s expedition. Peru at that time was much like the American Old West in the way that history became mythologised almost as soon as it happened.

At the top of the pass was a tiny chapel where the driver and passengers got out to light a candle. From here one could see the wild lands of the Vilcabamba ahead, a great ridge of snow-lined peaks with savage indentations between. It was no wonder that the Spanish were said to have drawn back in horror from the region whenever they saw it. The sight would certainly have silenced the loose braggarts of the party who had set off from Cuzco on the assumption that this would be some sort of glorified hunting-party, a nostalgic recreation of the glory days of the Conquest. If the punishing climb of the 14,000-foot pass had not already given them an intimation of the hardship to come, this first view of the Vilcabamba would have brought home to them all that real blood was going to be spilt and that it would be a test of bravery and endurance to bring the last of the Incas out of a region grid-locked by canyons, jungle and mountain ranges.

Looking down, I remembered the magnificent opening lines of the Peruvian novelist Ciro Alegría’s La Serpiente de Oro (The Golden Serpent):

Por donde el Marañón rompe las cordilleras en un voluntarioso afán de avance, la sierra peruana tiene una bravura de puma acosado. Con ella en torno, no es cosa de estar al descuido. (Where the Marañón River breaks through the mountains in a headstrong surge of attack, the Peruvian sierra has the fierceness of a cornered puma. Just as with the river, it is wise to treat it with respect.)

La Serpiente de Oro is the first of a trilogy of novels Ciro Alegria wrote in the 1930s as a powerful meditation on the relationship between the people of the mountains and those of the jungle. The narrator of La Serpiente is a young cholo, a lad from the jungle, and he disdains the mountain people who come down to his village

whimpering about mosquitoes. They would spend the whole night sensing snakes nearby, for all the world as if they’d laid their ponchos down on a nest of them … They don’t eat mangoes because they think it will give them fever. Even so, they still die shivering like wet dogs. This isn’t the country for the Indians of the mountains and there are only a few who ever acclimatise. They find the valley-bottoms too febrile. Meanwhile, for those of us of the jungle, the solitude and silence of the mountains tightens our chests unbearably.

The Spanish plan was to encircle the Incas in their stronghold and force them down into the jungle. To this end they had sent other expeditions around the Apurimac from Cuzco, to close off all the mountain passes that led from the Vilcabamba. Only the northern exits to the Amazon would remain open to the Incas. The one problem with this strategy was that it might be successful – and then the Spanish would themselves have to go down into the jungle after them. For the Spanish, as for the Incas, this was the last place they wanted to wage a war.

Both sides shared a largely paranoid and irrational fear of the snakes, mosquitoes and wild animals waiting for them, although the threat of disease was very real. So too was the well-earned reputation of the Antis and the other jungle tribes for being some of the most effective fighters on the continent. The Antis’ archers with their poisoned arrows were particularly lethal and were capable of defeating even the Spanish. When Manco had held Ollantaytambo against the conquistadors, these jungle archers had been one of his greatest assets.

Manco had been careful to forge alliances with the network of Amazon tribes behind his back when he arrived in Vilcabamba, and his successors continued those alliances after his death. During the time of the Inca Empire, the jungle had always been the least desirable posting and the site of some of the Empire’s worst defeats. At one point the Emperor Topa Inca had become separated from his troops and managed to get lost in the jungle: he was found only after a frantic search party was sent by one of his generals. While the Incas expanded dramatically north and south along both the Andes and the coast from their base in Cuzco, their expansion into Antisuyo, as they called the eastern quarter of the Empire towards the Amazon, had always been a shallow one.

The Antis (Antisuyo was named after them) had a tradition of wholesale cannibalism that appalled the Incas as much as the Spanish. John Hemming told an amusing story of Titu Cusi wanting to impress a Spanish envoy called Rodriguez who had been sent to parley with him. The Inca summoned up a phalanx of jungle warriors who paraded in front of them and then offered to eat Rodriguez for the Inca if he so desired. The Inca, to Rodriguez’s relief, turned down the offer, but the psychological effect this had when relayed back to the other Spanish in Cuzco can only be imagined. Certainly no one in the Spanish ranks can have relished the thought of heading into the jungle to meet them.

They would also have remembered the disastrous missions of men like Aguirre and Orellana into the jungle, missions in which most of the participants had died – and that Gonzalo Pizarro had, after all, succeeded in doing precisely what they were now doing thirty years before, when Manco was still alive and he had driven the Inca down into the Amazon. Yet Manco had survived, spirited away from tribe to tribe to re-emerge later and reclaim Vilcabamba when the Spanish had left it.

Something of the dangers of the Amazon area entered deep into the Peruvian psyche of the descendants of both the Spanish and the Incas and has remained to the present day. It is still adentro, the land within, hidden and dangerous. In Alegría’s novel, the outsider who comes to live with the people of the jungle is at first seduced by the beauty of the river and the landscape, but is ultimately killed by it. Even now it is still remarkably unoccupied and communications remain abominable: there are many tribes who have only recently been contacted for the first time, and doubtless many more remain.

As we descended below the pass, a red-hawk flew by. This was wild, isolated country. Spanish moss hung over a landscape of pines. It was difficult to tell which trees were alive and which were dead. Great spills of red earth ended in abrupt cliff-faces. There was something Arthurian about it, a landscape of the Grail quest, the ‘Sankgreal’.

We passed a truck that had gone off the road and down a canyon during the night. The skid marks were fresh in the mud. It must have happened only a few hours beforehand. The truck lay upturned, about a hundred feet below the road. We stopped to help, although there seemed to be no sign of any survivors. Oranges and apples were scattered pathetically down the side of the hill to where a local campesino was trying to hack his way across the steep bamboo to get to the upturned truck. ‘Buenos Dias,’ he shouted up to us in a voice that was startlingly cheerful.

The landscape began to change lower down; small-holdings were growing coffee, some huts had papaya-trees outside, there were daktura lilies hanging overhead with their uniquely rotting, decadent smell, bromeliads in the trees, huge poinsettias and then, to my surprise, nestling in the verges as an odd touch of the suburban amongst this vegetal opulence, large clumps of busy lizzies, grown to a size that would win prizes at any village horticultural show in England.

On the other side of the valley I could see that the slash-and-burn methods of the campesinos had destroyed large sections of hillside. Apart from bamboo, very little grew back afterwards to replace the vegetation once the land was abandoned, as it invariably was. The slash-and-burn method was notoriously wasteful of top-soil and had been made illegal in Peru, although this was hard to enforce. ‘Señor, a fire starts, what can we do?’

It was ironic to think that when the first Europeans arrived they initially presumed that because the forests were so tremendously fertile, their agriculture would be as well. Much has been made of the subsequent destruction of the rainforest itself, but how cruel it must also have been for the first settlers, after laboriously clearing and sowing their first crops, to see the top-soils washed away by the rains once the retaining and protecting vegetation had been burnt. It must have been baffling to them that trees grew to hundreds of feet in height, yet the soil was too light to support more than a single crop of corn.

I was reminded of one theory about the decline of the early Mayan civilisations in Central America: having over-stripped the surrounding rainforest to maintain a growing population, they could not sustain the resulting imbalance and the cities imploded, aggravated by civil wars and a punitive theocratic system, leaving the rainforests to come back and take over. For an ecologist the story has a particular savour (‘The rainforest will indeed come back and prevail!’), but as an example of the inability of man to maintain even the most advanced of civilisations in the face of hostile natural conditions, it has a certain sadness.

The technique of slash-and-burn, although the most short-term of solutions, would never quite go away in the Andes, for it did allow at least one brief crop to flourish before the land became useless. Transient farmers could move on after every crop. The effect was disastrous in the valleys, where it led to landslides like the one that had swept away the railway line.

The tendency of the Incas always to build high, on the sides or tops of valleys, could be attributed to a prudent aversion to such landslides – although the cynic could also point out that perhaps only the high ruins survive. There may have been many buildings on the valley floors which have been systematically destroyed over the centuries as landslides and floods occurred.

The bridge at Chuquichaca, which Roddy and I had crossed some two decades before, had been completely swept away by the flood. There were still some twisted remains of railway-line here and there, and a carriage on an old bit of siding.

It marked the point where the Vilcabamba river joined the Urubamba. Just as in Manco’s day, this was one of the essential strategic points for the Spanish advance: again they managed to cross it and started to make headway along the banks of the Vilcabamba river towards Vitcos. However, not much further along, the track came to a narrow pass, crossing a spit of land with a drop either side. Red rice grass fringed the verge, so that we looked through a curtain of red at the ferociously steep gorge of the Vilcabamba river below.

It was here that the Incas ambushed the Spanish, attacking with courage and ferocity. An Inca captain leapt on Martin Garcia de Loyola, one of the expedition’s leading captains, and tried to topple with him over the ravine edge. Only the prompt action of García’s servant, who slashed at the Inca warrior with a sword, prevented his death. Crude clubs and axes were as usual no match for Spanish firearms and although they killed a few of the enemy by rolling boulders down from above, the Incas retreated from this minor skirmish the losers.

When we reached the valley bottom, the sweat and smell began to rise inside the bus. We stopped to get a tyre fixed, to the indignation of many of the passengers. ‘This was supposed to be an express service,’ muttered the fat lady who had so enjoyed the Hawaiian-shirted magician’s performance. She got up and started to berate the driver. ‘This should all have been checked before the bus left. The mantenimiento just hasn’t been done properly. You can see the whole bus is dirty.’ She wiped a finger on the back of a seat-cover in the manner of an aunt from Blackpool and advanced menacingly. The driver maintained his equanimity impassively, given that he had 200 pounds of prime Andean womanhood bearing down on him. He gave a magnificent shrug. ‘Lo arreglamos, we’ll fix it’, he declared. But the other passengers had now taken up the cry: ‘Vámanos, vámanos! Let’s go, let’s go!’

‘I tell you what,’ said the driver, as if making a magnanimous gesture, ‘we’ll stop early for lunch.’ Quite how this made any difference to our arrival time was unclear, but we were treated to a bowl of disgustingly awful stew with glops of potatoes and unidentifiable meat – from a place which clearly gave the driver both a commission and a free lunch.

It was nightfall before we reached Huancacalle.

*

Seeing it in the moonlight, with the tall eucalyptus groves surrounding it, made my arrival there some twenty years before, huddled in a truck and trying to evade the police checkpoints, seem even more phantasmagorical. Huancacalle now had a small hostel, set up by the Cobos family. It was spartan, but it had a shower and more importantly it had beer.

Leaning against the doorway was the tall, rangy figure of Gary Ziegler. Gary was an explorer who had worked in this area for thirty years. In his stetson and breeches, he looked as if he might just have stepped off a Colorado ranch – as indeed he had. Gary was a true vaquero, a cowboy. Part-owner of a hundred head of horses back in the States, he mixed his exploring with ranch management. In fact Gary mixed his exploring with just about everything else in the Tom Sawyer logbook of jobs for active boys: over sixty years of enjoyably hard living, he had worked as a photographer, mountain guide, geologist and yacht handler.

Once, after a trip exploring the Vilcabamba, Gary had arrived at a local train station, left his hired horse (he insisted on riding everywhere) and rolled wearily into the carriage with his companions. The Quechuan Indians on the train gave them a wide berth, but Gary and his crew were too tired to worry about what might be wrong. Finally one Indian sidled nervously up to Gary: ‘Excuse me, Señor, but I’ve been talking with my friends and – are you Clint Eastwood?’

Over some vicious vodka martinis that Gary mixed up (I learnt later that he never travelled anywhere without a bottle of vodka and some green olives) we swapped stories.

Gary, like me, didn’t like the Amazon much. ‘I worked in intelligence in South-east Asia during the Vietnam war, and I tell you that was enough jungle for me. Used to go out on night patrols with infra-red vision to pick the enemy out with. Then we’d get those suckers. I tell you, being in the army is fun – at least in wartime. In peacetime it’s kind of dull.’

He had climbed most of the major peaks in the area and many of the minor ones. ‘I like those little suckers,’ he said, ‘the little insignificant peaks that no one else is ever going to bother with. Most have never been climbed before. Hell, most don’t even have a name.’

I had originally got into contact with Gary via the Internet and discovered that he too had taken an expedition to Choquequirao. After swapping e-mails, we were now about to go together to one of the most remote and little-visited of Inca sites, that of Inca Wasi in the Puncuyoc hills. My interest in the place had been stimulated, as so often with exploring, by the discovery of a map.

*

I had first seen it at the apartment of the distinguished archaeologist Adriana von Hagen.

The map was in an old brown cardboard tube. Adriana had inherited it from her father, Victor von Hagen. She carefully extracted the two-foot-square piece of parchment paper, covered in the thin red lines of Inca trails which gleamed on the translucent paper. It was the only copy of an only copy of an only copy. The original map had been made in 1921 by Christian Bües, a pioneering German explorer of the Vilcabamba who had finally died of drink and poverty. His map (entitled ‘El Señorío de Vilcabamba’, ‘The Kingdom of Vilcabamba’) had later come into the hands of a certain A. Palma, who in 1937 had copied what must have been the tattered original. This in its turn had come to the attention of Enrique Bernigau, a German doctor living in Urubamba, who had again painstakingly copied it and passed it on to Victor von Hagen when he came through Cuzco in 1952. Von Hagen had not done much exploring himself in the Vilcabamba, but he had directed colleagues of his on the Inca Highway expedition to do so.

Bolivians picnicking near the start of the Takesi trail: ‘¿Anda Solito? on your own?’ ‘Already twenty-one? You need a wife.’

The Takesi trail in Bolivia, descending towards the Yungas lowlands.

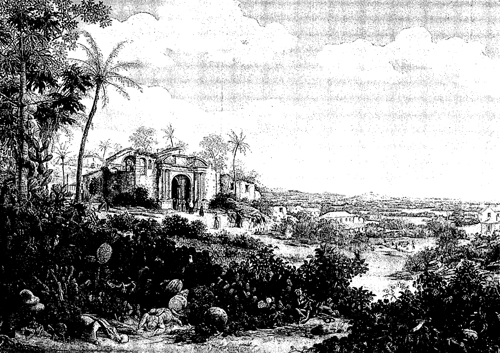

Frans Post, View of Olinda, Brazil, 1662. Painted eighteen years after the painter’s return to Holland from South America. ‘In South America, events of the distant past are often foreshortened and looked at with startling clarity.’

John Everett Millais, Pizarro Seizing the Inca of Peru, 1846.

Lake Titicaca.

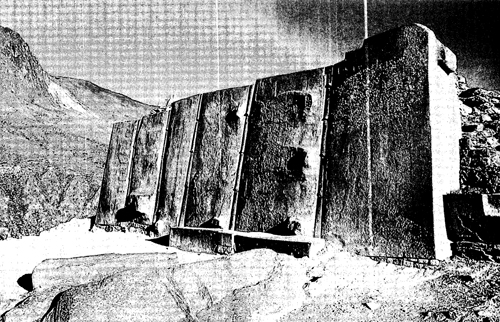

Ollantaytambo: ‘These great upright monoliths of pink porphyry were almost all that remained of the sun temple. They were arranged so as to face the rising sun, and had some of the strange bosses and protuberances that so intrigued me.’

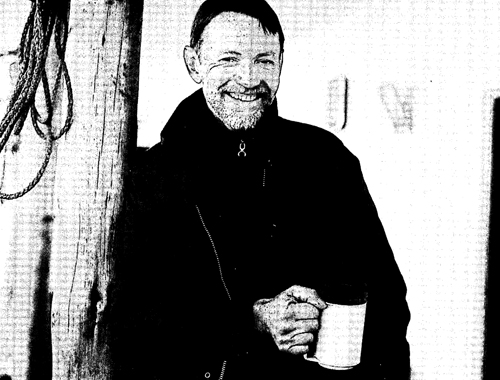

Gary Ziegler, at the Cobos family house in Huancacalle when I first met him: ‘he looked as if he might just have stepped off a Colorado ranch – as indeed he had.’

Camp near Inca Wasi at dawn, with Pumasillo massif beyond.

Inca Wasi in the mist: one of the highest of all Inca sites at 13,000 feet.

Chuquipalta, the White Rock.

Chuquipalta, the White Rock: the northern side, with projecting bosses.

Just below the pass of Ccolpo Cosa, on the descent towards Old Vilcabamba, the ‘last city of the Incas’.

Rónal with the horse that threw us both.

Gene Savoy, discoverer of Old Vilcabamba at Espíritu Pampa in 1964: ‘“What you have to remember,” Nicholas Asheshov told me, “is that Gene Savoy is a cult. A real this-man-is-the-centre-of-the-universe cult.”’

The ruins of Old Vilcabamba at Espirítu Pampa, ‘which Bingham liked to translate literally, as the “Pampa of Ghosts”: the rain forest had taken over completely.’

The reason that it had been so carefully preserved from one generation of explorers to the next was clear to me as soon as I saw it. Bües had obviously travelled far more extensively and thoughtfully than had ever been fully appreciated. His map was far more detailed than many I had seen from more recent years: he also appreciated fully the significance of the road network that linked Choquequirao and Vitcos.

Victor von Hagen must have seized on it. In his handwriting was a tiny cross he had added just off the map, to the north, in a range called the Puncuyoc hills. It was a place he had discovered but few had been to since, called Inca Wasi, one of the highest of all Inca sites at 13,000 feet. It was an irresistible temptation and I felt my blood rising as soon as I saw the map. I had to go there myself.

At least this time no one had painstakingly to sit down and spend what must have been a week’s work tracing the map. Adriana took it down the road to a Lima photocopying house who specialised in large-format architectural drawings, and within five minutes I had my own copy.

*

The Coboses’ house was almost the last house in the village of Huancacalle and had been the jumping-off point for most of the post-war expeditions into the Vilcabamba. They were a dynastic family of guides. Benjamin Cobos had travelled down to Espiritu Pampa with Gene Savoy in the sixties, José Cobos had worked with Vincent Lee in the eighties and now Juvenal Cobos and other younger members of the family were helping Gary and me on our expedition to the Puncuyoc hills and that little cross on the map.

We headed back to the small village of Yupanqa and started to load up the mules. As I knew from years of experience, this was not as straightforward as it might have seemed.

The procedure for loading mules is very similar to that which an elderly aunt of mine adopts when going on holiday. First the muleteers lay out all the bundles on the grass and move them around until they look deceptively ordered and graded. Then these bundles are packed into saddlebags and onto the mules (in my aunt’s case, suitcases). Like her, the muleteers will invariably decide that everything is in the wrong place and must be taken out so that the process can be started all over again. The mule you most need to do this with has got bored and absconded over the horizon.

Experienced arrieros can spin this process out for hours. We were lucky and got off that same morning. In Bhutan, my film team were once compelled to spend the night on a Himalayan pass because the wranglers had managed a tour-de force delay of four hours in loading the pack-animals.

Of course, one technique is to forget the mules and head on up a path in the hope that the muleteers will catch you later. But this, particularly on the first day of an expedition, can remain just a hope.

As we started up into the rugged, igneous peaks of the Puncuyoc hills and looked back, we could see why Vitcos was such a convenient centre for the Incas in their exile – it was the hub of a wheel, with spokes extending not only into the Puncuyoc, but away towards the jungle at Old Vilcabamba and up the Choquetecarpa pass towards Choquequirao: beyond were various areas around Pumasillo and Arma that remain under-explored. In the centre Vitcos rose up, a natural location for Manco’s successor to use as Lords of the Vilcabamba.

As befitted a cowboy, Gary had made sure that we had riding horses for the trip. This was a novelty for me, and not a wholly welcome one: I was used to keeping two feet firmly on the ground. While the idea of occasionally mounting up and letting the horse do the work was agreeable, I suspected that the narrow overgrown paths wouldn’t allow for much manoeuvring. Gary had a friend along with him on the trip called Joan Harrell, who looked equally fit – she alarmed me by saying that she’d trained for this by running marathons. The most exercise I had taken in recent months was to get the coffee and bring it back to the film cutting-room. It was going to be an unequal contest.

We set off up the hill at a ferocious rate, made harder by the fact that while the trail was initially surprisingly good, Gary suggested we lead rather than ride the horses. My own horse sensed that I was not a natural horseman so I had to pull it up most of the way. Just when I was regretting my lack of fitness, the others started to talk about ‘running up the mountain, because walking’s so boring’. They even had trainers packed for the eventuality. I put my best foot forward and thought of the vodka martini at the end of the day.

After a brisk 3000-foot ascent to a stopping-place for lunch, we saw a short, flat, open section extending ahead of us for a few hundred yards, before the trail re-entered the selva. ‘This is where we get to ride,’ said Gary. We duly rode for five minutes, before dismounting and leading the horses downhill for the rest of the day. Although mollified when Gary and Joan said that I was the first person who had ever managed to keep up with them, dragging a reluctant horse around the Andes in full sun was not my idea of fun. I asked a little petulantly what the point of having the horses was. ‘Exercise,’ replied Gary laconically.

By now anyway Joan was not feeling well – a combination of altitude and unfamiliar diet had taken its toll. She looked pale and had taken a full hit of 500 milligrams of Ciproxin. (There is a prevalent theory among expeditions in the Andes that it’s better to have one huge dose of antibiotics rather than follow a course through to the end – an idea which runs satisfyingly against all medical orthodoxy.)

The diet was getting to us all. Gary was so flatulent that he could have been heard on the other side of the valley. ‘Sorry about that,’ he apologised. I couldn’t resist. ‘Don’t worry, Gary. If you hadn’t said anything, we’d have thought it was one of the mules.’

Below us down a ridge was the camp-site and our jumping-off point for the exploration proper. We were above the cloud-line and had a spectacular view of the Pumasillo mountain range rising up ahead. Mt Pumasillo has a curious characteristic: despite being 20,000 feet high, it is so shielded by a host of lesser mountains as to be completely invisible to the surrounding valleys and villages. Only when some distance away does it reveal itself: it was not even accurately put on the map until 1956.

Our cook’s name was Aurelio (what with our chief guide Juvenal, we seemed to be in the middle of some classicists’ convention) and he had gone ahead to prepare a dieta de pollo, steaming chicken broth with a large hunk of bird in the middle. Aurelio, like most camp cooks, had a few quirks (in his case cooking delicious food hours before it was needed, so that it had grown cold by the time we ate), but he was a dab hand with the machete, whether for cutting up chickens or undergrowth. On a memorable later occasion he slaughtered a sheep he’d brought with us over the mountains. After hanging it for a day in a nearby tree, he roasted the carcass in hot stones and ichu grass for the Andean dish known as pachamanga.

I sat up late with Gary and Joan, talking about previous expeditions. Gary had enormous energy for archaeological exploration and an instinct for finding the spoors of long-forgotten Inca roads and buildings that came from years of hunting them down. He also brought an immense range of knowledge to his exploring, from geology to obscure forms of cattle disease, fuelled by an obsessive drive that had kept him coming back again long after most men would have hung up their boots. ‘The thing is, guys like us are all a little off-centre,’ he told me. ‘Explorers have to be. Otherwise we just wouldn’t do it.’

That night I tried to keep quiet about the fact that I had a self-inflating sleeping-mat (sleeping on the ground had been fine twenty years before, but now I needed a little comfort) and after a couple more of Gary’s vodka martinis I sank into a strange dream that was a badly shot melange of cinematic clichés: for some reason, I met Tobias Schneebaum at the airport, who showed me a photo of himself years earlier, alone in the jungle. ‘Naturally it’s in black and white,’ he said in his New York drawl. Then I was on the plane without a ticket, knowing that I had no ticket and waiting to be discovered. In a hammy moment, my dream-vision pulled focus past the approaching stewardess, who looked Hitchcockian, blonde and reproving, to an envelope with my name on it tucked into the bulkhead beyond. Inside, I felt suddenly sure, was my ticket. I woke up just as the plane started to spiral down towards the jungle.

Mist swirled around the tents. The cloud had risen around us during the night. Even though we had Juvenal and José Cobos with us, who had worked with those few explorers who had come here before, it was tricky finding the way. To help us there were some sections of Inca stone-laid path and an unusual amount of miradores, stone platforms built out from the contouring path from which (on a clear day at least) one could view the valley. These were good signs of an Inca presence, but nothing prepared us for what lay ahead.

As we came through two miradores flanking the path on a shoulder, the path widened dramatically and there were traces of an Inca bridge crossing a stream. We looked up. The wind was blowing the mist and in one clear gap we saw a glimpse of what was unmistakably Inca Wasi high above us, a single dramatically gabled building right on the ridge with (just as at Machu Picchu) a summit rearing up behind it. Then the mist closed in again.

I remembered the words of Stuart White: ‘The site has no particular strategic advantage but it is awesome for the size of the mountain at its back and the depth of the valley falling away below it.’

Stuart White was the first explorer to have seen Inca Wasi before he wrote about it. Others, such as Victor von Hagen, had relied on reports and this had led to their making substantial errors (von Hagen had even claimed it might be the lost city of Old Vilcabamba, a wild guess from a man who hadn’t been there). Nor had the archaeologists been much better: White noted sharply in his subsequent report that while two prominent Peruvian archaeologists, Victor Angles Vargas and Edmundo Guillén Guillén, had discussed Inca Wasi (Vargas hypothesising that it must have been a communications post), ‘unfortunately neither of these investigators have actually reached the site’. White had written his report as recently as 1983. I was continually surprised at how young such real knowledge about the Incas was.

One dramatic feature about Inca Wasi is its elevation. It stood at 13,000 feet. By way of comparison, Machu Picchu, which most visitors feel to be up in the clouds, is at a mere 8000 feet.

White had made a convincing case for this being the site of the oracle that the Emperor Sayri Tupac, Manco’s son, was known to have consulted in 1557, before leaving the Vilcabamba. By then, the Inca guerrillas had been holed up in the province for twenty years. After Manco’s death, Sayri – made of less stern stuff than his father – began to find the continuing rigours of existence in the highlands not to his taste. He finally succumbed to Spanish blandishments and the offer of a comfortable existence back in Cuzco (with lands, a title and protection) – but not before going with all his advisers to consult this oracle on a high mountain near Vitcos.

We began the climb up to it along an extraordinarily well-built path, which showed Inca Wasi to have been a destination of some ceremonial importance: it was a finely laid Inca causeway some ten feet wide in places, which negotiated the marshy side-valley before entering a tangle of trees that over the centuries had uprooted some of the thick stone blocks. The forest was so overgrown that I needed my machete to hack a way through. At times the road faded, but then emerged clearly again, cut into the side of the slope and contouring around, with views of the small side-valley below. As we got higher, the vegetation became gradually more stunted, shrouded in mosses, lichens and epiphytes.

I thought of Sayri Tupac being carried up here on his litter to consult the oracle, with the sound of his trumpets filling the valley and the priests and attendants ahead of him. The writer of the contemporary Relación Francesca had witnessed just such a procession: ‘There were in front of him [the Inca] many Indians who cleared the road in spite of the fact that it was rather clean and there was nothing to pick up.’ The Incas would have fasted all that day, and by tradition no fires could be lit along the way for warmth. By the time the stone path climbed above the tree-line, they would have been bitterly cold. Even with several layers of polar fleeces and a thermos of coca tea, I was still shivering.

I climbed the last stairway alone, as Gary and Joan had stayed below for a while to look at a small site on the approaches. The stairway mounted in a sharp and slightly uncharacteristic zig-zag, perhaps determined by the unusually steep slopes. As I came up the final rise, the building was in front of me, a terrace with nine trapezoidal niches rising up to a two-storeyed building, steeply gabled, positioned on a knife-edged ridge that spread the cloud to either side.

It was remarkable for being so well preserved, partly because at this altitude it was above the tree-line; trees can be more destructive to old Inca stone than erosion or even the attentions of huaqueros, the treasure-hunters. The local granite stonework had probably been originally covered with a red plaster and there were still residues of it in some of the niches. With its two storeys and high gables, it reminded me of the great buildings at Choquequirao, and like Choquequirao it had stone eye-bonders set into the wall. These curious and finely worked rings of stone had exercised the imaginations of many investigators in the past. The Comte de Sartiges, the early French traveller to Choquequirao, had wondered fancifully if they were used to tether pumas – although the more likely and mundane use may have been to secure hanging doors and textiles.

The American explorer Vincent Lee had described this as being ‘one of the most elaborate, best preserved examples of Inca architecture in existence’. But as fine as the building was, it was what you could see from it that made for a memorable experience. As the mists cleared again, I witnessed a remarkable phenomenon. On the other face of the valley was a monumental rock, which had a striking white spot on its summit. From Inca Wasi, this spot was perfectly reflected in the lake directly below, with an odd ghostly effect of white on water. ‘Jesus,’ whispered Gary softly as he joined me. It seemed as if the building was placed to be precisely on the sight-line for this reflection – and we later saw that Inca stonework had been used to dam the lake below, thereby creating the effect artificially. If you moved just a few feet away from the centre of the terrace the reflection was lost.

The building of Inca Wasi had a clear spiritual axis: to one side lay the valley of Vitcos and the Inca’s temporal domain; to the other, in this hidden valley, lay what must have been the oracle, for the striking reflection in the waters of the lake cried out for divination.

The Inca captains were in great difficulties as to whether Sayri Tupac should depart from the Vilcabamba. They held many meetings and conferences on the matter until the day of Our Lady in September 1557, when all agreed to make sacrifices according to their custom and to ask for a response from the Sun, the Earth and the other huacas that they had. And so, on the morning of that day, having ordered that all should fast and that no fire should be lit, all the captains climbed a high mountain and the Inca went with them, with his trumpets, taking with him and in front of him the priests, who are greatly respected and strictly obeyed. The priests then asked the Sun, the Earth and the huacas to declare if the departure would turn out well. When that was done and the omens had been read, the priests said that they had received from the Sun, the Earth and the huacas the reply that the departure would be successful and fortunate. All their questions had been answered with ‘yes’, in contrast to the requests that they had made at other times, when other governors had tried to arrange a departure.

(Diego Fernandez, Historia del Perú, 1571)

So Sayri Tupac left Vilcabamba and was rapturously received by the Spanish. As it turned out, the oracle was wrong, at least for Sayri personally. After his conversion to Christianity, he was allowed to live on the old royal estates of his grandfather Huayna Capac, at Yucay in the Sacred Valley, which contained many contemplative lakes of the sort we had seen below Inca Wasi. However, the estates had been severely reduced by both Spanish colonists and the predations of a local Cañari chieftain called Francisco Chilche (originally moved there under the Incas’ mitamayo policy) who, like most of his tribe, hated the Incas with a vengeance – a vengeance which in his case he may have taken personally, as when Sayri Tupac died suddenly three years after his surrender, Chilche was arrested on suspicion of poisoning.

It must have been a miserable last few years for the displaced Inca – walking in the ravaged remains of what were once great pleasure gardens, humiliated by the meanest conquistador who chose to insult him and surrounded by former subject-races who were naturally hostile. Even surveying his gardens in the fertile Yucay valley can have given him little enjoyment. The exotic fruits and plants his ancestors had grown there – the cucurbitae, the coca, the sweet potatoes, the peanuts – were once imperial symbols of Inca victory over the far-flung provinces where such rare produce originated. Now they would have been reminders of all that they had lost.

Yet for the Inca State (and the increasingly powerful priesthood who had interpreted the oracle for Sayri Tupac), the decision that he should leave may have been the right one. It completely wrong-footed the enemy. When Sayri left the Vilcabamba and his subjects, he also – unbeknown to the Spanish – left behind the borla, the ‘royal fringe’ and insignia of the Emperor which was worn around the head: Sayri told the Spanish he wasn’t wearing it because he didn’t want to offend them by claiming imperial jurisdiction, a ruse the legalistic Spanish accepted hook, line and sinker. The Spanish naturally assumed that they now had control of the Inca and therefore of any further rebellion. It was some time before they realised that his much tougher brother Titu Cusi (who had narrowly escaped being assassinated with his father Manco when he was just a boy) was not only wearing the borla in his place, but firmly intended to maintain the independent rump-state of the Vilcabamba.

With Sayri’s premature death in 1560, Titu Cusi came out into the open as the new and extremely competent Emperor. Unlike Sayri, he showed no signs of weakening towards the Spanish, although he was very capable of pretending to accede to their demands whenever it suited him. The Spanish still had a problem in Vilcabamba, and it was to be a further ten years before they regained enough political momentum and Viceroy Toledo sent his final expedition to try to capture Titu’s own successor, Tupac Amaru. On the expedition, heading his troop of Cañari Indians, was that same Francisco Chilche who had been accused of murdering Sayri Tupac.

By now it was getting late and we stumbled down in the gloom. In the dark, the trees that had ripped up the old Inca causeway took on a malevolent Arthur Rackham aspect. Lower down we came to an area where fire had cleared away the thick shrub, always a boon to the explorer if not to the ecology: Gary spotted some Inca stonework off to one side. ‘It’s mine, it’s mine,’ he shouted excitedly as we rushed over to examine the perfectly formed stone bath built up over the stream bed. Below, by a path we had not previously taken, there was more – a small complex of waterways and buildings near a waterfall and a large chunk of phosphorescently white granite, at about 11,000 feet. The baths here had a beautifully channelled water system, with overflows and complex drainage. It was clear that Inca Wasi was only the very apex of a whole set of buildings and that many of those were in the ‘pleasure building’ category I was familiar with from Machu Picchu and Choquequirao. Had Manco (and perhaps later his various sons) built this site up not only as an oracle but as a moya, ‘a place of leisure’ for his own personal retreat in the manner that his great antecedents had done in more liberated days? Even in exile (perhaps particularly in exile), the Inca would have wanted to continue the lifestyle to which an Emperor was accustomed.

We passed a small pile of roofing-pegs by the lake that had been prepared for insertion but never used. There were abandoned hammer-stones nearby. These seemed to testify to the mournful idea that work on the complex was abandoned before it could be completed, just as at Ollantaytambo and Choquequirao.

It was getting dark and we still had some distance to travel, but with the euphoria of these findings it was difficult to drag ourselves away. As we crashed down through the jungle following a trail that José Cobos had cut for us, trying not to trip over roots in the approaching gloom, we saw building after building loom up out of the dense greenery. ‘This is exciting,’ said Gary. ‘It’s like Chachapoyas. These are ruins all around us.’ It would take a later expedition (and some serious clearing) to see what was there.

It was another few days before we returned to the valley and the road-head. We had camped by a lake called Llana Cocha (the Dark Lake), with Andean gulls and black loons flying overhead, near some simple pre-Inca circular stone foundations. The field nearby had been freshly hand-ploughed, almost like archaeological test-trenches (if a little less carefully than archaeologists themselves would have liked) and shards of crude, simple pottery lay everywhere.

On the last day, Gary and Joan decided they were going to ‘run off the mountain’ and were wearing little running shorts and extremely technical trainers to do so. ‘We’ll wait for you and Aurelio at the bottom.’ Originally this had not seemed such a bad idea – Aurelio was terrific company and had some good Quechuan jokes if we were to make up the slower rear party – but as the two runners set off, something in me bucked at the thought of being last, perhaps spurred by Aurelio’s gentle jibe about being the tortoise to Gary’s hare. I took off down the mountain myself and, despite heavy boots and a full pack (and laughing too hard), found I could not only keep up with Gary and Joan but easily outdistance the Americans – mainly by the technique of using boots to scrunch down the scree while they jogged more genteelly on the path itself. With some elation, if breathlessly, I found myself the first to run across the bridge at Yupanqa, 3000 feet below.

It is an image that is anyway a staple of Andean exploration: emerging out of the selva at midday after a long trip – the wide brown streets, with brown houses, everything brown and stark from the overhead sun – the gringo lumbering down the main street, silhouetted with his backpack, walking loose, already punch-drunk from his discoveries before he’s even had a beer. It felt delirious and wonderful.

*

Back at Huancacalle, it was time to revisit the White Rock itself. The walk from the village up towards Chuquipalta was as lovely as ever. Opposite the Coboses’ house were little pools for breeding trout, and the river came down with a freshness that sang out against the silvery grey of the eucalyptus groves. As I climbed, I could look back on the village – it seemed virtually unchanged after almost twenty years. Indeed, the whole valley was still remarkably unspoilt and must have looked much the same to the Incas. The one exception to this, the groves of eucalyptus trees (a later import brought over from Australia for their resilience and good timber), now looked as natural to the valley as chestnuts in an English landscape.

A small boy came down the hill with his sister and some friends, on their way to the village school. They asked if I had any money or biros. I didn’t, but I had a bright blue glass button in my pocket, a good luck charm. I squatted down with the kids on the ground, took the button out and told them that it was mágico and that if one of them closed his eyes and made a wish, it would come true. The kids’ eyes opened wide and I told the boy to shut his tight as he touched the button. He gripped it hard. Then I whispered to him close, so that none of the others could hear, ‘Lo que quieres más en el mundo, vas a conseguir’ (‘Listen, whatever you want most in life, you can achieve’). Then they went on their way.

I crossed over the meadows. An electric-green rocotillo snake threaded its way elegantly across the grass. The White Rock still loomed up like a battleship out of the meadow, with its extraordinary carvings and coursed waterway leading to an Inca fountain nearby. It seemed as little visited as ever. I had borrowed the key from the curator down in the village, whose log-book showed only a handful of travellers coming through. The key was for a gate in the cursory fence that had been put up around the rock to keep the cattle out (most of them seemed to be inside the fence anyway), but the site itself was exactly as I had remembered it.

If there had been any changes, it was in the sensibility with which I now looked at it. Twenty years before there had been a reluctance to consider such stonework aesthetically. Archaeologists were still so concerned with function (which was often difficult to ascribe to the carved free-standing stones of the Incas) that the accomplished sculptural quality of the work had received hardly more than a passing nod. The feeling that these carved stones were exclusively religious in purpose had also side-tracked any aesthetic assessment. While Western critics could quite happily ignore the religious connotations of a Renaissance Maestà when discussing an Italian artist, they seemed to be inhibited by the far less specific religious connotations of pre-Columbian work.

Perhaps because I was trying to secularise what had always seemed to me an excessive tendency to attribute spiritual values to every Inca monument, I found it easier to see the stones for what they were: quite extraordinary sculptures. And of all the many examples I had seen, the White Rock was still the most extraordinary of them all, each side a developed yet unexpected part of the whole. On one side a glissade of rock, with a water channel carved into it; on another, a symmetrical descent of huge sloping steps cut into the granite; and on the highest wall, the series of asymmetric bosses projecting spectacularly from the sheer granite. By any standards it had to rank as one of the world’s finest sculptures, even if it had been parked in some white-walled gallery. Here, in a small side-valley of the Vilcabamba, with the flow of surrounding mountains behind, it was luminous. The original whiteness of the stone had long since turned to dark grey with the growth of lichen, but the shape shone through.

Nor was the White Rock alone. Scattered over the meadows for some way below, in amongst the arum lilies and the grazing cattle, were many other carved stones in what was a veritable sculpture park. One, a carved chair, was similar to a Henry Moore: others followed the usual tactful Inca convention of allowing the stone still to speak for itself, while adorning and shaping edges. In any other part of the world UNESCO would have declared it a world heritage site. Yet in the days I spent there, the only visitors were two English girls who surveyed the site from on top of the rock like conquerors and departed within five minutes.

However, the feeling that these stones had validity as sculptures was slowly spreading. An Argentinian artist called César Paternosto had written a book, The Stone and the Thread: Andean Roots of Abstract Art, challenging the archaeologists’ hegemony over the carved stones, and trying to reclaim them as art. Although he hadn’t written about this particular site, César had some interesting comments on the strange bosses or protuberances the Incas often used, which had made such a strong impression on me the first time I had come to the White Rock.

Archaeologists in the past had performed intellectual contortions to try to explain why these bosses protruded so dramatically from otherwise flat walls of carefully hewn granite. Were they unfinished work, or props to lean the stones up with before they were dropped into place? Or were they used for some unspecified religious purpose (as when they occurred at religious sites like the Coricancha, the Sun Temple, in Cuzco, or at Ollantaytambo), such as to hang sacred weavings? I had seen similar curious bosses at Machu Picchu, on the so-called ‘House of the Princess’. Some commentators had speculated that they might be weathered corbels supporting some form of shutter. To me they seemed purely decorative, and decorative in a flamboyant way. The bosses called attention to the sheer virtuosity of the granite carving which could leave such vivid protuberances coming back out from the rock, like faces through a sheet.

They were sublime stone-working which served to demonstrate a supreme mastery of the material – to leave such bosses in place is to work completely against the grain of the stone. César suggested another parallel idea. Much has always been made of the fact that the Incas had no formal system of writing, but relied on a system of knotted cords, the quipu, to pass on information. The quipu was an old Andean tradition which the Incas had inherited from the Huari. Knotted cords in different colours were hung from a central cord, and these knots could then be ‘read’ by skilled interpreters, the quipucamayos. (César had quoted the Taoist master Chuang Tzu, who said that ‘keeping records on knots was the sign of a happier, earlier age’.)

The conquistadors had frequently lamented this system (and evidenced their own system of writing as one of the benefits that a more advanced society could bring). It is only recently that scholars have shown the quipu to be a more inventive and flexible means of recording information than a mere mnemonic device to inventory the Inca holdings. It may, for instance, also have been used as an aid for story-telling, a historical prompt.

César had compared the logic of the quipu system with its random system of knots, which remain indecipherable today, to the similarly indecipherable protuberances, or stone knots as he described them, across the face of the carved stone. It was an exciting idea. Rather than functional work whose function we did not understand, the bosses could be considered as being expressive and significant, writing with stone.