The case of Frederick Ransom was written by his brother, Daniel, in his unpublished manuscript, “Memoirs of Daniel Ransom.” Although the script was written many years after the incident, when Daniel was in his eighties, it still brings home the dilemma that New England people faced in regard to the evil disease consumption. The incident took place in 1817, based on the recollections of Daniel. It is a classic example of how families turned to folklore and superstition in a desperate attempt to stop the dreaded affliction that was taking their loved ones to the grave.

Many notable figures have hailed from the bucolic Vermont town of Woodstock since its settlement in 1768, but it is also well known for its ghosts, peculiar monolithic structures and vampires. The Ransom memoir appeared about the time of Exeter, Rhode Island’s Mercy Brown exhumation, having been acknowledged in 1894. About this time, articles and stories were popping up in just about every publication, from small-town papers to major scientific journals. It appears that the New England vampire had finally sunken its teeth into the annals of history.

Frederick Ransom, a twenty-year-old Dartmouth College student born on June 16, 1797, died of consumption on February 14, 1817. Frederick’s father began to fear that his son might rise from the grave and begin to feed on the rest of the family, thus taking them to their graves. He therefore sought to have Frederick exhumed and his heart cut from his body and burned in order to save the family from imminent death. Daniel was only three years old at the time of the incident but recollected the eerie event with strikingly vivid detail.

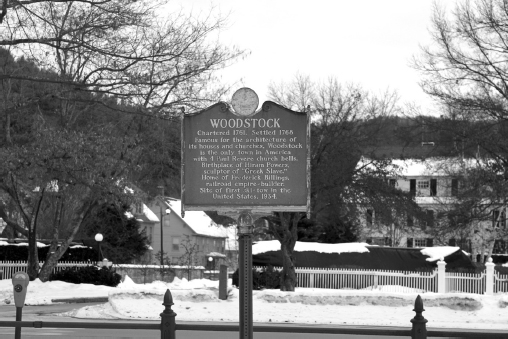

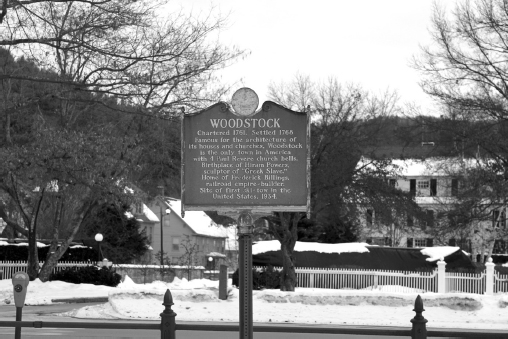

The quaint little Woodstock Green in Woodstock, Vermont, where a vampire exorcism was said to have taken place, twice. Photo courtesy of Victoria Julian.

The family was told that consumption, the early name for tuberculosis, was hereditary in the Ransom family. As stated before, many doctors and researchers believed that the disease was hereditary and not a contagious affliction. Even young Daniel was told that he would never see old age, as the white plague would take him to the grave before his thirtieth birthday. Daniel’s father, being perhaps a bit desperate and superstitious, ordered Frederick’s body to be exhumed and his heart to burned at Captain Pearson’s blacksmith forge. The cure, however, failed to work; Mrs. Ransom died in 1821, followed by a daughter in 1828 and two sons in 1830 and 1832. Once again, we see the blacksmith forge being used as part of the ceremony for the exorcism of the evil that was upon them. Mothers used to pass their sick babies over the forge of a blacksmith in hopes that its magical powers would cure the toddler’s ailments. Some went as far as having the blacksmith tap the child, who was laid upon the anvil, three times in the afflicted area with his hammer.

The Ransom account was published in the Vermont Standard in the 1890s. The manuscript resides in the Williams Public Library on Woodstock Green. For the rest of the century, families would use the same grisly method in hopes that this remedial effort might put an end to the infirmity that was ravaging New England households. Perhaps this is why Mr. Ransom decided to write his recollections at the time he did. By then, exhumation was a somewhat common occurrence in New England. Rider’s Book Notes, Stetson’s “Animistic Vampire” and the pamphlet on consumption and its causes in New England by Dr. Henry Bowditch (see chapter on Saco, Maine) undoubtedly received some press. Coupled with the many other articles from reporters and newspapers, it seems that it was almost in vogue to write of vampirism, which was, years before, a shunned topic.