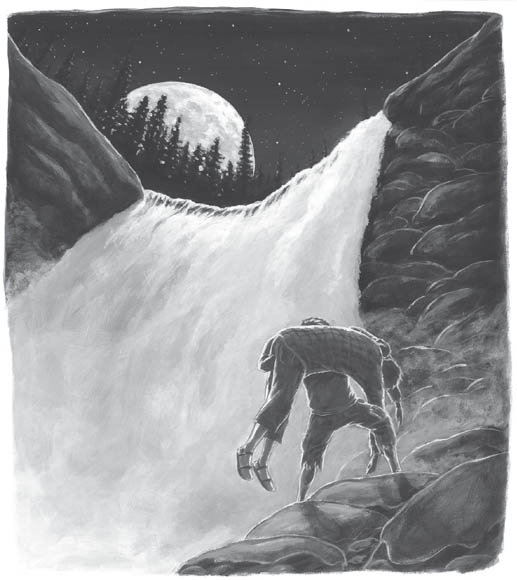

The more I look up at the path beside the waterfall the more I realize Dad can’t walk up it, even leaning against me. It’s too dangerous. If one of us slips, we’d both topple back into the raging cauldron below.

I have to think. But there’s no time for thinking. But I have to think anyway. The path is dark, but I see a glow through the trees above, up on the edge of the canyon.

It must be the moon. It should be almost full by now. Dad says something. I can’t make out what he’s saying over the roar of the waterfall.

“Louder, Dad!” I bend my head down near his mouth.

“You go. I can’t . . . walk. Go get . . . help.”

“No way! I’m not leaving you down here. You’re coughing up blood. You’ll freeze.” He’d attract some hungry grizzlies for sure, but I don’t say that out loud. “Just let me think a minute.”

We haven’t seen anybody else the whole trip, not a soul. Just one canoe broken in half. Other paddlers should be coming behind us in a day or two, but we don’t have a day or two. Dad won’t make it that long. Rangers are supposed to patrol periodically, but we haven’t seen even one. It’s probably not worth their while if it’s just a few of us paddling the circuit now. We’re registered at the ranger station, but Dad estimated we’d be back in eight or nine days. It’s only been six. They won’t start missing us for a few days.

We can’t wait that long. We have to get out now. I have to find a way.

Just then the moon breaks free of the trees and shines down on us, and I don’t know why, but suddenly I know what to do. What I have to do.

I take some deep breaths and say, “Dad, we’re going now. It’s time to go.”

I hunch down and slide my arm and shoulder beneath him, plant my legs and feet into the ground like a weight-lifter . . .

. . . and I lift!! I mean, I lift him clear off the ground! And into a fireman’s carry—slung sideways across my shoulders.

Dad’s taller than me and outweighs me by at least twenty pounds, but thinking of Cassidy carrying my dad up out of Desolation Canyon two years ago gives me a shot of pure energy. Superhuman strength.

Still, I creak under his weight and I feel like I’m going to snap in two. But feeling that energy coursing through me, I keep waddling in a half crouch, and start slowly, very slowly, up the path.

One step at a time.

I climb through a cloud of mist, the roar of the waterfall, with Dad on my back, across my shoulders—dangling, deadweight, huffing, groaning, but not saying anything. Wheezing.

First one switchback, then another. Up and up. Endlessly up and up and up.

After a few minutes, exhaustion starts taking its toll, but it’s also taking the chill out of my bones. I’m sweating. I’m soaked. Sweat, river water, spray from the waterfall.

I don’t know if I can keep going. I need to stop and rest. But I’m afraid that if I put Dad down, I won’t be able to lift him back up.

So I keep taking one step, and then another, and another.

I’m gasping. My heart is thumping, pounding, in my chest, in my ears. My thigh muscles are burning, my calves. My knees and hips are straining, tearing, aching.

I keep trudging with my load up the hill. And then I remember that dream I had. The grizzly bear carrying the moon up the mountain. The Moon Bear. Almost making it to the top.

Then falling, tumbling back down the mountain with the moon.

And starting up all over again.

But I can’t fall. I can’t tumble down the mountain. I can’t start all over again. I have to keep going. Keep climbing. Up and up. Up toward the sky.

Finally, just when I think I’m going to die, I see the top of the path. Another fifty yards. Half the length of a football field.

But farther, really. Much farther. Because of the switchbacks.

But I keep going. Seeing the top sparks hope. Hope that I will make it. I will make it. I will make it.

We make it!

We make it to the top of the canyon and I lower myself down to all fours, then slowly swing Dad around and let him slide slowly to the ground.

I flop beside him, sprawled out, gasping. My chest heaving. I close my eyes and see stars. I open them, and see stars, dimmed a bit by the rising moon. It’s getting close to full.

Suddenly Dad coughs. An awful, ragged cough. He tries to sit up and gags. He tries to clear his throat. He launches into an attack of coughing.

I roll him on his side, patting his back.

We have to get going. The dampness and chill are creeping back into my bones. Dad must be freezing. We’re both wet.

And hungry. Hunger’s like a fish hook tugging my guts.

And the more we wait here the hungrier we will get. The colder we’ll get.

I take several deep breaths. I rub my legs and shake my arms and roll my head around, and try to loosen my shoulders. And take more deep breaths.

Then I say, “Up we go, Dad. It’s a bummer, but we’ve got to go.”

Again, I sneak my arm beneath him, my shoulder. First I lean him against a boulder. Then I sink into a deep squat and heft him onto my shoulders and lift. With all my might, I lift.

We’re up. I almost fall backwards. I catch myself. I start along the path.

One step at a time.

When we start descending I figure it’ll be easier now. But my knees keep buckling beneath me. It’s easier on my lungs, but even harder on my legs.

Thinking of fish and a fire, I get a second wind. I try to think of gravity as my friend. Along with gravity, my friend, we are climbing down now. Down.

I think of Cassidy. He carried my dad up the walls of Desolation Canyon, but two or three of us helped get Dad back down.

Now it’s just me. And gravity. A tricky friendship.

There’s less than half a mile to go.

It’s the longest half mile in the world.

I round a bend and finally see the moonlit lake below. Dad’s dangling arms and legs are swinging with each step I take.

I think he’s gone unconscious again. I fall into a kind of stupor from exhaustion, but I don’t let go. I swing my legs and stumble along, like a dying but loyal beast of burden.

Time disappears. One leg shuffles in front of the other. Down and down and down we go.

One step at a time. Until . . .

The lake the lake! We’re at the lake!

I don’t stop. I can’t stop. We have to get back to our camp. Fifty yards to go. Forty yards. Twenty.

At last, I strain with my last ounce of strength and lower my dad next to the fire ring. We both collapse on the cold ground. I’m totally exhausted. And dehydrated. I need water, but I can’t move.

And Dad, he’s out. He’s out cold. I want to get him out of his wet clothes and into a sleeping bag, but I don’t know how I’m going to do that. I want to drink water and make a fire and catch a fish and eat. Especially eat. And feed my father.

Wanting isn’t the same as doing.

I’ve got to do this.

I shake myself awake and glug some water from my water bottle and try to think. We have to eat. We have to get dry. And warm. We have to rest. To sleep.

A cold wind blows down from the mountains. I have to try to get a big fire going. Now!

First I pull Dad’s sleeping bag out of our tent and over to the fire pit. I fluff it out next to Dad, and roll him on it, then pull it closed over him. I lift his head and stick his small pillow beneath it. I’ll have to get his wet clothes off him later, after I get the fire going. No time now.

Luckily there’s a small stack of firewood leftover from before. With the moon and stars as my only light, I set a few of the slenderest pieces into a little tepee, with some birch or aspen bark—whatever, it’s like stiff but brittle paper—shred it into a fire nest, then twist the last of our newspaper and stuff it underneath.

Dad had left the four remaining matches in an empty tin of mints, in the tent, and I get it.

I kneel by the fire and I think to myself, Okay, here goes!

And I strike the first match against a large, rough stone.

The head flies off. Bummer!

Three matches left.

I try striking this match less forcefully, but nothing happens. I keep trying till the head is worn down to a nub. To nothing.

Two. Two matches left! Dad groans. I check him out but he’s still out cold. The moon is high overhead. The night is bright and clear and cold.

Okay. This is the one! I will the match to light, and with fumbling fingers, scratch it across the stone.

It breaks in half! My heart breaks with it.

I feel like giving up, but I’m obsessed with getting this fire started.

I’m obsessed. I put all my concentration into the last match.

The last match!

I focus on it with all the power of the universe funneled down to this one match.

And strike.

It flares up!

And goes out!

A whiff of smoke spirals into nothingness.