13

Clutch waited for the night he wanted – a clear sky with a south-easterly breeze bringing scents of dangers ahead. He already knew some things from analysing the wind from the top of the chimney on previous nights. And his mother, though she had never been very far east, told him what she’d heard from gossip at the community latrine. This is what Clutch knew:

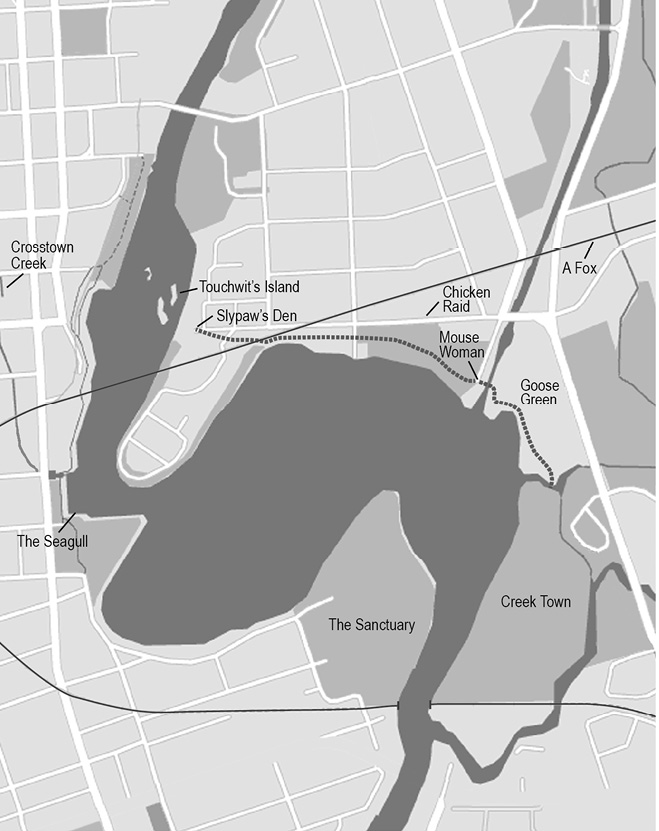

His biggest obstacle would be a Primate thoroughfare. Full of traffic at any hour, it was a treacherous crossing. The road marked the eastern boundary of the inner city. Beyond it lay a neighbourhood of newly built houses without a mature tree to climb or porch to hide under in a crisis. And some houses had fenced yards containing Droolers and every Drooler that was imprisoned outdoors had to be considered vicious. The neighbourhood was no place for raccoons. Yet it would provide sanctuary if he had to escape from the powerful raccoons who made up the Clan Fathers. They wouldn’t risk going into the suburb.

He also knew that if he could find a creek amid the new housing, he could follow it northeast into the countryside. The creek was an ancient pathway for animals travelling into the city from afar, bringing them to where it drained into the Lake. Here the prosperous raccoon settlement called Creek Town had flourished since antiquity, but he intended to travel upstream, away from raccoon society to seek his fortune.

Clutch was the first of the cubs to go. He touched noses with his brother and sister, committing their scents to memory – he might never see them again. Then he gave his mother the hug that a first-born son gives when he is about to start his journey to become a man.

Clutch left the roof by the front-door cedar and travelled with the Great Raccoon Ancestor high in the southeast sky pointing the way.

“I wasn’t sure then,” Clutch subsequently recalled, “what it was I was seeking. I just felt it had something to do with the Great Spirit and with my Father. I felt that to become my own self, I had to find my relationship with my celestial and earthly forebearers. Was it a service to one of them I was meant to perform? Was it a problem between them that I was supposed to fix? I didn’t know. But I set out with a high heart, knowing I’d find the answer.”

He must have gone east along the arterial street that runs across the top of the lake. I know this because he recounted coming to the spot where Uncle Wily was killed by an electric car. He sniffed his death-place, but no trace of his spirit lingered on the road, only oil and rubber on the worn asphalt. Yet the moment with his uncle was powerful, and as Clutch honoured the only relative he had known as an infant he hoped that some of the old raccoon’s wisdom passed into him. Then he picked his way parallel to the street through the back gardens of houses on the lake until he came to his first obstacle.

A canal extends up the east side of the city from Little Lake. It was constructed a long time ago to take people up to the lumber mills and summer resort hotels, getting around the rapids and power dams on the river. Today, the canal carries yachts and touring boats. Clutch had to cross the canal before he faced the next obstacle – the hazard presented by the adjacent highway. The best way across the canal, which his mother mentioned without enthusiasm, was to sneak south down a canal service lane. A row of poplar trees flanked the lane, offering a series of evenly spaced escapes. Just before the canal met the lake, he would find a walkway along the top of a canal lock. He’d have to cross it in the dark with water plunging twenty feet down from a sluice. It led through some pines to a park extending around the northeast corner of the lake directly to the creek, and if he went upstream, away from Creek Town, he would find a culvert that would get him under the highway. If he ran into trouble, he could find refuge in the ancient raccoon colony.

From his account, it seems Clutch reached the canal without incident. He cleared his mind of a distracting scent of chickens kept in the backyard of a nearby house, and analysed his rejected options. Yes, the swing bridge in front of him was just as his mother had described it – a lifeless, metal monster daring him to dart across between vehicles. He noted the railway bridge to the north. A way for animals to cross the canal, it might be handy in a crisis. But the service lane to the south was right where his mom said it would be, and he scampered under the swish of poplar leaves in the breeze, south to the lock. And crossing the narrow wooden walkway wasn’t as dreadful as he feared. The experience was over in an eye blink. He crouched in the pines waiting for his heart to stop racing and then took a pathway through the park around the shoreline of Little Lake in the direction of Beavermead Creek. Strange that there were no fresh raccoon scents. Creek Town was a major raccoon community at the juncture of creek, lake, parkland, and forest. He ought to have been challenged by a sentry before now. Instead he was challenged by a serious danger.

Geese! And many of them, and they had goslings! This meant they wouldn’t be relying on their usual half-hearted hissing to warn off a territorial nuisance: they’d be ferociously aggressive. A warning hiss, and the males would charge straight at his face, striking his head with powerful shoulder bones, biting and kicking, driving him away. He couldn’t detour around the flock through the pines to his left because the geese would think he was stalking their goslings; for the same reason, he couldn’t take to the water where the geese had an advantage. Time for diplomacy. Were geese open to reason?

Clutch looked up to the sky for guidance. There, outlined by stars, the brilliant form of his Ancestor said “No!”

“What should I do then?”

“Use your clever Raccoon mind.”

Clutch consulted his clever raccoon mind. There was a puzzle here. What was it? The geese were sleeping except for the periodic honk of all’s well by the designated watchgoose. They hadn’t sensed him downwind. But why were the geese here at all, so close to the top of a raccoon town? Geese wouldn’t be parenting goslings near raccoons, and from the scent of the goose scat the geese had been here for awhile. Where was the huge Creek Town clan family?

Only one way to solve this puzzle. Ask the geese.

Clutch approached slowly. He perched on his hind legs at intervals to make himself conspicuous in the gloom. A series of urgent honks. The geese rose with effort to their feet and began bobbing their heads, spreading alarm. He stood still and looked away from the flock so as not to appear to be an intent predator. No effect. The mothers were leading their goslings towards the water while the fathers covered their escape. One enormous Gander stood his ground, the rearguard for the flock.

“Pisssss off! This is our pasture. We have children.”

Standing still and looking away was completely useless. The Gander advanced, loosening its wings and arching its neck.

“I do not intend harm. I am only a solitary Raccoon of no consequence looking for my Clan.”

“You’re a Carnivore, and your very existence is an insult to Grazers. Also, you’re full of tricks.”

“I assure you I will not interfere with your parenting.”

“Go home and mind your own business, which is eating garbage.”

“I beg passage through your grazing place to the Beavers’ creek, where I hope only to be reunited with my own kind.”

“Forget it! There are none of your kind there. They have taken flight, which you ought to do too before I peck out your eyes.”

Witnessing the standoff, the other male geese turned and began advancing behind a barrage of hisses. Clutch counted six family heads, full of attitude. Geese had the impulse of many flocking creatures to excite each other into a state of frenzied purpose. If they attacked him, he wouldn’t be able to run away. He conceded ground in slow, deliberate movements, always facing his attackers. He tried to appear relaxed, though he felt tense as a closed clam. Also, his feelings were hurt. He was a peace-loving raccoon. True, he had a predator’s impulses, but they were well under control.

Clutch walked away alone, not daring to look back at the self-satisfied ganders.

It wasn’t until he was back on the west side of the lock that he felt himself unstiffen. All through the confrontation his hackles had been raised, contradicting his peaceful intent. So much for diplomacy.

Clutch lay under a poplar tree and licked his paws, recovering his dignity and his options. Why did he let a self-superior goose stop him? He could have charged right at the bird, grabbed him by the throat, flipped him over wings still beating, and bit into his neck, sucking his blood. Only the certainty that the other geese would have swarmed him had prevented him from asserting himself.

But then when he’d settled down more and his heart had stopped pounding under his ribs, he began to recover his reasonableness. No, he’d never go head-to-head with a pumped-up goose. Or anybody, for that matter. The impulse was silly. It was against his principles. Ever since he was a cub, he had committed himself to the refined reasoning of diplomatic persuasion instead of the coarse logic of fight or flee. He took after Uncle Wily who avoided bloodthirsty aggression.

But where had diplomacy got him? He was back on his home side of the canal. His Ancestor was splendid in the sky, on the distant side of the canal. And he was feeling hungry. Aggression gave a person the munchies.

Clutch picked himself up and went north on the service road to the lockmaster’s house. Here, where boaters came ashore to use the washrooms and tourists gathered to watch the lock in operation, there were recycling bins. But first, he scented sandwich crumbs beneath a park bench against the wall of the house. And what was that tiny scuffling noise around the corner? Someone else was looking for crumbs. Someone succulent to feed a hungry raccoon.

Clutch waited in the dark until the mouse crept around the corner. One pounce and he had it between his paws. A quick, merciful decapitation, then he’d chew its body with leisure. But the object in his hands began to speak:

“Oh, please don’t eat me, Sir. I am but a tiny mouseling with no flesh on my bones and scarcely worth the swallow.”

Clutch instantly regretted that he hadn’t devoured the mouse on the spot, for now his supper was reasoning with him. “Why shouldn’t I eat you? You’re a Rodent,” he replied. He picked up his prey by the tail and carried it in his mouth around the corner of the gatehouse, dropping it under his paw below the light from an outdoor lamp. Grey, with a white belly. A Field Mouse. Too young to be a mother.

“Reasons why you shouldn’t eat me. Number One: everyone is moving away from meat to plant-based substitutes. Two: you’re not really all that hungry anyway. You’re feeling out of sorts, and people shouldn’t try to get out of their depressions by eating comfort food. Three: …”

“If you had as much muscle as you have reasons, I’d have eaten you before you opened your mouth.” Clutch tried not to sound piqued. Prey had no right to argue with their predators. That wasn’t how the system worked.

“Indeed, I was stupid enough to make myself vulnerable, and you caught me fairly,” the mouse went on. It certainly was a chatterbox. “However, people nowadays like to be responsible for their actions. They like to know why they are doing what they are doing, the context of their decision as well as its consequences. Especially when it involves a member of a minority.”

“Since when did mice become a minority? They are underfoot everywhere, and they multiply like fleas.”

“I am a minority in the sense that I am the victim of an imbalance in a relationship of power, for instance between a responsible Raccoon and an errant Mouse.”

Clutch closed his eyes and prayed to his gods until the rage provoked by this display of impudence passed. First he prayed to the Great Raccoon Ancestor who gave Raccoons their cleverness. Then he prayed to the First Mother, consort of the Spirit Ancestor, she who is called Hapticia, who bestowed her hand-eye coordination on all Raccoons. Meanwhile, the animacy was watching him keenly with its bright eyes. He felt its little heart beating in his paws.

“Since when did you corner the market on victimhood?” he asked it.

“I didn’t. We are all victims. The world is a mean place, and it’s getting meaner by the minute.”

“I’m not a victim,” Clutch said.

“You’re not? Where is the River Clan Family?”

“You tell me, if you know so much.”

“Its people are cowering under porches and in tree hollows from here to the horizon. Like mice.”

“Who is preying on them, to make them as cowardly as mice?”

“That is for you to find out. But don’t let your mission distract from my main point. My point is that most of us are victims in this unbalanced world. We are all minorities.”

Clutch grew tired of this argument. It sounded like one of those paths of reasoning that led to an entanglement, and it was only delaying the inevitable. He cleared his throat for a gulp. This victim was going down the chute. Conversations about bully versus victim power imbalances were going down with it. What next? Were vegetables going to start arguing with their eaters?

“Besides,” the mouse said casually. “You shouldn’t eat me because I can tell your fortune.”

Clutch hesitated again. It was bad enough to be bested by a Goose. But now a Rodent full of a pesky pertinency. Yet in all fairness, he should hear it out. Mice don’t know much, but what they know is close to the ground.

“What do you know about my fortune?”

“I know that you are going to squeeze through a tight space into your future. And that you will become a responsible Raccoon.”

“You could be less vague.”

“You have kinfolk hiding nearby in a boathouse on the lake. They haven’t eaten in nights and they are hungry.”

“I am hungry too, but you’ve taken away my appetite,” Clutch said, releasing the mouse. “Now I don’t want to eat anymore.”

“Neither do I.”

“You’ve made me pointless, moody, and malnourished.”

“But you’re a better Raccoon.”

“Anytime you want to have a disquisition on moral philosophy before lunch, let me know,” Clutch said gruffly.

“I will. Cheers.”

The mouse curled her tail above her ears and watched the raccoon turn sharply away and walk stiff-legged back down the service road in the direction of the lake.