CHAPTER 26

Battle of Santa Cruz

25 October

Sunday—what a day of rest! Dispatches indicate Jap push on Guadalcanal. 2 CV, 2 BB, 2 CA, 3 CL, some DD moving down in support of 6 AP’s. Halsey’s orders to us and to TF 62 (Enterprise, now back in the area, plus Hornet): “Strike.”

The Nicholas (449) has joined giving us 10 DD. We are fairly far out, but push off at the Washington’s near top [speed], a shade over 26. At 1400 we go to G.Q. just as we start past the N. side of Rennell Is. Visibility not too good; ceiling low; no shadowers—but shore observers on Rennell, plus previous shadowers plus our position, make air attack likely. Plan is to enter the inland waters of the Solomons West of Guadalcanal, make a sweep through the area the Japs have used for landings, bombardments, etc., and smash anything we find. Frequent rain squalls, maybe a close-range, shot-guns-across-the-dinner-table, sort of affair.

At sunset we take battle disposition, 6 DD in van; Atlanta supporting van DD’s; San Francisco, Helena, Washington as main body, next in column; 4 DD’s rear. Weather now clearing, Guadalcanal in sight to N 50 miles or so; prospects are now for good visibility, which with the full moon make surprise unlikely.

At 2200 we turned North, passing West of Russell Island, into the expected enemy area. Went North, then NorthEast, then East, then Southeast, headed directly for Savo. Meanwhile San Francisco had catapulted three planes to search the area, moonlight now being very bright and visibility phenomenal. Their reports showed no Japs present, and off Savo we turned to 220° and stood out. Secured from G.Q. at 0230, and then I had the 4–8 watch! So it goes.

26 October

Headed S. at 25 kt, expecting air attack. Shadowed all morning by a Nakajima 97 twin-float seaplane, probably from Buin, and then by a Kawanishi 97. No immediate developments, but we spent some hours at G.Q. during time of expected attack.

Got the news of what the carrier group found the 25th—the night of our foray that found us arriving to see the bird flown. Theirs hadn’t. Hornet lost, also Porter (356) in an engagement off the Stewart Island to East of Solomon area, with a strong Jap force. Hornet got several bomb and aerial torpedo hits and had to be taken in tow by Northampton. A second attack then got to her, as a result of which it was decided to torpedo her—which I suppose has been done; haven’t heard. Enterprise was there, as were our 3 sister ships and the South Dakota—must have been a heavy air attack to get through that effectively. Although its success is of course enhanced by our phony carrier tactics, which I have long decried. What corresponding damage we were able to do I dunno, but am afraid it falls far short of being worth it. So now we are back to one carrier, again.

27 Oct

Sub took a shot at Washington this morning, no doubt put on the trail by yesterday’s shad. Missed. One detonated at end of run, between her and us, another ran right up our wake, porpoising, and sank about 800 yds away. Evidently, her spread was fired from extreme range, outside our screen. They have about 20 subs known to be in this area, so can afford long shot at such of our remaining effective units as they find. Needless to say, we got the hell outa there, continuing on Southeast, to fuel.

***

By midday on October 24, Task Force 64 was positioned equidistant from Cactus and Button and steamed on a variety of courses in waters that had been dubbed “Torpedo Junction,” awaiting an opportunity to steam north to engage Japanese naval forces. That opportunity appeared the next day as Imperial Japanese naval forces closed on Guadalcanal in anticipation of a breakthrough by Lieutenant General Maruyama’s Sendai Division. As Japanese destroyers appeared off Lunga Roads mid-morning, the contact report reached Lee before noon, and the powerful American surface flotilla surged on the northwesterly heading at 22 knots. At the time of the sighting, Lee’s ships were to the southeast of Rennell Island, a large coral island located some 100 miles directly south of Guadalcanal.1

By 2000, Task Force 64 was positioned off the southwestern quadrant of Cactus, and an hour later, Washington, San Francisco, and Helena each launched scout planes. At 2154 Atlanta’s war diary recorded “Changed Course to 000°(T),” and six minutes later Lee’s ships slowed to 22 knots as they inserted themselves into the slot.

With the Japanese surface forces having extracted themselves before sunset, Lee’s scout planes searched in vain over the moonlit waters northwest of Cactus for any sign of a Tokyo Express column or a flotilla of Japanese heavy warships charging down for yet another bombardment mission of Henderson Field and environs in support of Maruyama’s last gasp attacks that evening. Satisfied that no surface engagement would occur that evening, at 0215 early on October 26, Atlanta stood down from General Quarters and Condition 3 watches were set. At 0315, now heading due south, Task Force 64 formed a cruising disposition, with the major combatants following Atlanta in column while the destroyers steamed parallel to Jenkins’ light cruiser in a line abreast. At 0535 Task Force 64 once again split. Task Group 64.1, centered on Washington and Atlanta, continued to steam south. At 0605 lookouts in Atlanta spotted a Japanese seaplane to the south, “well beyond gun range.” By 0800, Task Group 64.1, now well clear of Cactus, steamed in waters west of Rennell Island.2

That afternoon, as Lee’s ships continued deeper into the Coral Sea, the screening destroyers took an opportunity to refuel with black oil that could be spared from Washington’s bunkers. As the destroyers took turns at the battleship fuel trough, Atlanta steamed astern in a lifeguard position. That night, Lee’s formation steamed well south of Rennell Island to stay out of range of Japanese carrier aircraft. However, as Lloyd recorded, submarines also posed a threat. At 0329, early on October 27, Lansdowne reported a torpedo approaching Washington. Having evaded the underwater missile, Lee’s force cleared the area only to find themselves facing another spread of torpedoes just over two hours later. Lloyd recalled that with dawn breaking, the ship had been called to General Quarters per standard operating procedures. He went on to describe what happened next:

… lo and behold, we had a submarine contact. The submarine fired torpedoes and everyone turned successfully to evade them including Washington. They had been firing at the Washington from the other side from where the Atlanta was so when they missed her they came on past us too. We just watched them run down each side as we threaded between them.3

The torpedo avoidance incident represented the closest Lloyd came to actual combat with the Japanese over the span of these three significant days in the Southwest Pacific. For his stepfather, the narrative would prove much different.

For several weeks since the loss of Wasp, Hornet—the centerpiece of Task Force 17—remained the U.S. Navy’s remaining carrier in the region, and Vice Admiral Ghormley used it sparingly, given the Japanese land-based air threat and reports of Japanese carriers. Fortunately, with the arrival of Hornet’s older sister Enterprise and Task Force 16 on October 24, the balance of naval power evened, though still favoring the Japanese. Not only did American carrier strength double, but with the return of the patched South Dakota, the American Navy now fielded 18 16-inch guns to take on a surface duel with Japanese heavies. Under the command of Rear Adm. Thomas Kinkaid, Task Force 16 brought an additional heavy cruiser Portland, the light cruiser San Juan, and eight additional destroyers. The return of San Juan meant that all four Atlanta-class light cruisers were serving in the region, with Juneau and San Diego assigned to Rear Admiral Murray’s Task Force 17.4

As the two task forces rendezvoused at 1400 on October 24, the more senior Turner took command of the overall American formation as Commander Task Force 61. Turner’s immediate superior, Vice Admiral Halsey, remained ashore at Noumea, having moved his staff off the cramped quarters that had been provided by Argonne. Halsey and his boss, Admiral Nimitz at Pearl, matched wits with their Japanese counterpart, Admiral Yamamoto, who maintained his flag on the super battleship Yamato at Truk. That this behemoth of a battlewagon remained well away from the action illustrated that the Japanese faced the same problem that confronted the Americans and their battleships in the earlier months of the war—fuel consumption.

That fuel was needed to sustain the Tokyo Express and maintain Vice Adm. Nobutake Kondo’s support force. Kondo steamed with the advance force, having Carrier Division 2 with the carriers Hiyo and Junyo backed with two battleships, five cruisers, and 10 destroyers. Fortunately for the Americans, the Japanese numeric flattop superiority dropped as an engineering space fire forced Hiyo to depart the area on October 21. Meanwhile, the bulk of Japanese striking power lay with the main body centered on Vice Admiral Nagumo’s Carrier Division 1, having Pearl Harbor veterans Zuikaku and Shokaku and the light carrier Zuiho. These carriers were lightly protected by a screen that included a cruiser and eight destroyers. Rounding out Kondo’s command, a vanguard force commanded by Rear Adm. Hiroaki Abe boasted serious surface firepower from two battleships, four cruisers, and seven destroyers.5

Despite the Japanese advantages not only in carriers but in surface combatants, Halsey intended to ease enemy naval pressure on Cactus. While Lee and Task Force 64 swung up from the Coral Sea to interdict Japanese forces coming down the slot, Halsey directed Kinkaid to take Task Force 61 to well northeast of Guadalcanal north of the Santa Cruz islands and sweep from east to west.

Though the Japanese held numeric advantages, the side with carriers that launched “firstest with the mostest” had the best chance of prevailing, so reconnaissance proved critical. On October 25, the Americans gained the supposed upper hand due to multiple sightings of Japanese forces by PBYs and B-17s, leading to a launch of torpedo planes and dive-bombers off Enterprise. However, Vice Admiral Nagumo, appreciating the consequences of being sighted, prudently reversed course and took his carriers beyond the range of Enterprise’s fliers who had to return to their carrier after sunset.6

Night-flying Catalinas with airborne radar not only continued to give the Americans a spotting leg up on the Japanese, but also an offensive capability. Having again reversed his course and wondering if the Americans were aware of his presence in the pre-dawn hours of August 26, Vice Admiral Nagumo found out when four bombs dropped from one of the American PBYs exploded a mere 300 yards off Zuikaku at 0250. Nagumo, fearing that the rising sun could obscure swarms of American carrier aircraft, again changed Carrier Division 1’s course to a northern heading. Unfortunately for the Americans, Rear Admiral Kinkaid embarked in Enterprise could not discern a clear picture of the Japanese forces from the nocturnal reports of the PBYs, so prior to sunrise the Big E launched a combat air patrol of Wildcats and eight pairs of Dauntlesses to obtain a positive fix on the enemy carriers.7

One pair of the SBDs came across Abe’s Vanguard Force at 0630 bearing west of Enterprise at a distance of 170 miles. Twenty minutes later, a second pair observed Nagumo’s main force to the northwest at a distance of 200 miles. Nagumo’s own combat air patrol chased away this and another pair of U.S. Navy dive-bombers that responded to the contact report, but a third pair found gaps in the Japanese fighter defense and pressed an attack on Zuiho at 0740, scoring a hit aft. Though Japanese damage control teams quickly extinguished the flames, Zuiho no longer could conduct flight operations and factor in the evolving battle.8

At the time the Americans had placed Zuiho out of action, that light carrier, along with the two heavy carriers, had already launched a potent strike of 62 aircraft in a southeasterly heading in response to a Japanese scout plane sighting of Task Force 16. Nagumo, confident his aviators would knock out the sighted American flattop, ordered Abe to steam east to close for a decisive surface action. If the first wave of Japanese dive-bombers and torpedo planes did complete the job, the follow-on smaller waves of Val and Kate aircraft would mop up what was left.9

As a total of 110 Japanese aircraft headed toward Task Force 16 as well as Task Force 17, a smaller cadre of American planes lifted off Hornet and Enterprise. Hornet provided the bulk of the American initial strike force with 15 dive-bombers and 6 torpedo planes escorted by 8 fighters. Whereas the Japanese used aircraft catapulted from battleships and cruisers for scouting purposes, the American practice of deploying scout planes from carriers limited the number of airframes available for a strike. That morning’s dispersing of 16 SBDs from Enterprise cut that carrier’s contribution to a mere 20 aircraft. A half hour after Hornet’ s first launch, Lloyd’s stepfather watched another 25 aircraft lift off and turn to the northwest.10

With two groups of warplanes heading to opposing objectives, not surprisingly they met along the way. As the Japanese were first in the air, their initial strike group had gained higher altitude. Somehow Hornet’s planes passed in the vicinity unnoticed, but their Zero escorts spotted the smaller Enterprise group and dove on the Americans. The ensuing dogfight cost the Americans four Avenger torpedo planes and four Wildcats, while the Japanese lost four Zeros and suffered damage to a fifth.11

Forewarned by radio and then radar, Hornet scrambled more fighters to meet the onslaught of Japanese aircraft that had George Murray’s task force in sight as Task Force 16 had slipped into a rainsquall 10 miles to the northeast. As Wildcats from both Enterprise and Hornet struggled to gain height to meet the oncoming attackers, Capt. Charles P. Mason brought Hornet up to 31 knots on a northeasterly heading, and her escort of four cruisers pinched in to increase the number of gun barrels aimed skyward. Off her bow, sailors on the heavy cruisers Northampton and Pensacola scanned the skies as did sailors on Atlanta’s two sisters, San Diego and Juneau astride her stern.12

Though those sailors could see some evidence of the Wildcats challenging the Japanese on the western horizon, the combat air patrol had been poorly directed and there simply were too many attackers. At 0910, nearly 20 Vals started to descend on Hornet one by one. Captain Mason’s evasive action plus voluminous gunfire caused the first two dropped bombs and bomb-dropping aircraft to fall to starboard of the bridge; however, three Vals scored bomb hits on the flight deck adjacent to the bridge, and between the midship and aft elevators. Another Val crashed against Hornet’s stack, spraying the signal bridge area with burning aviation gas. The remnants of the plane and its undetonated bomb reached the crew’s galley, setting off an intense fire.13

The skill exhibited by the Val pilots was matched by Japan’s torpedo plane crews as they divided into two formations that approached the burning carrier from two directions, assuring that a turn to straddle one spread of fish would simply expose Hornet’s broadside to a second set. Two torpedoes pierced the carrier’s hull. One on the port side punched a hole into the forward engineering space, and the other hit on the starboard quarter into compartmentalized spaces. In one final blow, another Val flying from astern flew over the bridge and plunged itself on the port side of the flight deck, eliminating a number of gun mounts and their crews.14

Only minutes after Hornet withstood what would prove to be fatal punishment, her aviators exacted some revenge on Shokaku. Dauntlesses scored hits, tearing up her flight deck aft of the bridge. Near misses also damaged the big carrier as well as a screening destroyer. Hornet’s torpedo planes, the following Enterprise planes, and the second Hornet strike, failed to locate Carrier Division 1 and attacked Japanese surface combatants if they could be found. The second group from Hornet, which included bomb-laden Avengers, located and delivered a savage attack on the cruiser Chikuma.15

Meanwhile, the Vals from Carrier Division 1’s second strike arrived in the vicinity of the two American task forces past 1000 and passed over the billowing Hornet to search further for the other American carrier. Having met nominal American fighter resistance, the Japanese dive-bombers located Kinkaid’s flagship and positioned themselves for their steep descent. Though guarded by fewer cruisers, with the heavy cruiser Portland close to her port bow and Atlanta sister ship San Juan to starboard, there was the battleship South Dakota astern. With the carrier’s and battleship’s recent repair visit to Pearl Harbor, both ships were each fitted with 16 Bofors rapid-fire 40mm antiaircraft guns.

As with the attack on the Hornet, the Japanese aviators scored hits at great cost. One bomb passed through the forward port flight deck only to travel into and out of the forecastle to clear the ship’s interior before detonating, and then a second hit the flight deck aft of the forward elevator, causing damage and death on both the hangar and third deck below. One near miss sent a shock wave through the ship that bounced a plane over the side.16

Unlike the attack on Hornet, the torpedo plane attack on Big E was slow to develop, and the combat air patrol and gunners would have ample time to test their marksmanship. Attempting to run the gamut of American ordnance, one Kate crashed into the forward 5-inch mount of the destroyer Smith. With a blazing forecastle driving the bridge team out of the pilothouse, Smith’s commanding officer calmly regained control of the ship from the after-steering station and maneuvered the light tin can under the churning wake of South Dakota, which served to dampen the flames. Those planes that survived the hot metal fired in their direction failed to score hits with their fish. Of the 44 aircraft used in Nagumo’s second wave, 24 would fail to return.

With still an hour before noon, the situation for the Americans grew more unfavorable. Hornet crippled, sought a tow from Northampton to clear the area as her engineers evaluated the damage, and contemplated getting steam up to get one shaft turning. Though still able to land and launch aircraft despite having its number two midships elevator locked in a down position, Enterprise was incapable of unleashing another strike at the Japanese. Though the Americans had forced Zuiho and Shokaku from the scene, the remaining heavy carrier Zuikaku and light carrier Junyo of Kondo’s advance force, along with an impressive array of surface forces, now provided the Japanese a lopsided advantage that they intended to press.

Junyo’s first strike of Vals passed over Hornet and arrived over Enterprise at 1121 as Task Force 16 ducked under the low cloud cover of a heavy rain squall, forcing the Japanese to glide in on their target. Though the defending gunners could only pick out the incoming attackers on their final approach, they splashed a number of enemy aircraft. Unfortunately, one bomb detonated 8 feet off the starboard side had the carrier heeled over to port, shuddering the ship and causing below-waterline damage comparable to that of a torpedo.

Junyo’s fliers also went after some of the other ships in the task force. San Juan became the first ship of the Atlanta-class to be bloodied when a bomb passed through her thinly plated stern section to explode beneath the ship, jamming the rudder in a full right position. With South Dakota’s AA batteries dispatching broadside attackers, one Val pilot took a head-on approach and successfully lobbed a bomb onto the battleship’s forward turret. Shielded under heavy steel, the turret survived unscathed but the exploding bomb fragments wounded over 50, killing two.17

As surviving Junyo pilots turned their aircraft homeward bound, Hornet and Enterprise aircraft returning from the raid on Nagumo’s carriers could finally be landed. Big E ’s landing signal officer successfully trapped 57 aircraft. Tragically, one Avenger damaged in the attack on Zuiho ditched ahead of the destroyer Porter, jarring its torpedo loose to commence an underwater voyage that, despite desperate strafing by overhead Wildcats, would end up hitting Porter between her boiler rooms, killing 15 of her crew. Rather than spare a warship to tow Porter out of harm, Rear Admiral Kinkaid elected to order Lt. Cdr. Wilbur G. Jones in Shaw to recover the surviving crew and sink Porter with gunfire—the first ship that day on either side to be sunk.

No longer fearing American naval airpower, Vice Admiral Kondo detached Junyo to join Nagumo’s main body and surged forward with his advance and vanguard forces to bring the Americans within range of his 14-inch guns. To delay any potential departure of the American forces from the scene, both Junyo and Zuikaku launched early afternoon strikes.18

Appreciating that the numbers now heavily favored the Japanese and having no interest in engaging in a gun duel, Rear Admiral Kinkaid ordered Task Force 16 to withdraw to the southeast. Kinkaid’s departure with Enterprise meant no air cover for a struggling Hornet that Northampton attempted to take under tow. Lloyd’s stepfather had transferred his flag to that cruiser just before noon. Meanwhile, destroyers pulled close by the crippled carrier to take off the seriously injured and hundreds of others who no longer were needed. Other sailors remained aboard to flesh out gun crews or work below to place at least one shaft back in operation.19

At around 1500 the Japanese aircraft arrived in the vicinity. Without air cover, Northampton released the towing line and presented a stern aspect to the slow descending Kate torpedo planes off of Junyo. Though Hornet’s gunners dropped several of the attackers, a torpedo struck on the starboard side at 1523 aft and above an earlier hit. It was a crushing blow that erased any hope of recovery as the ship listed close to 15 degrees. As Junyo’s torpedo planes departed, Vals from Zuikaku arrived and scored near misses by Hornet and San Diego. Bomb-carrying Kates made a level bombing run, dropping a pattern of projectiles of which one penetrated the stern of the doomed carrier. By this time Captain Mason had ordered the remaining crew to abandon the carrier that had once carried Doolittle’s raiders on their famous strike on the Japanese homeland. Mason was last to step off at 1627.20

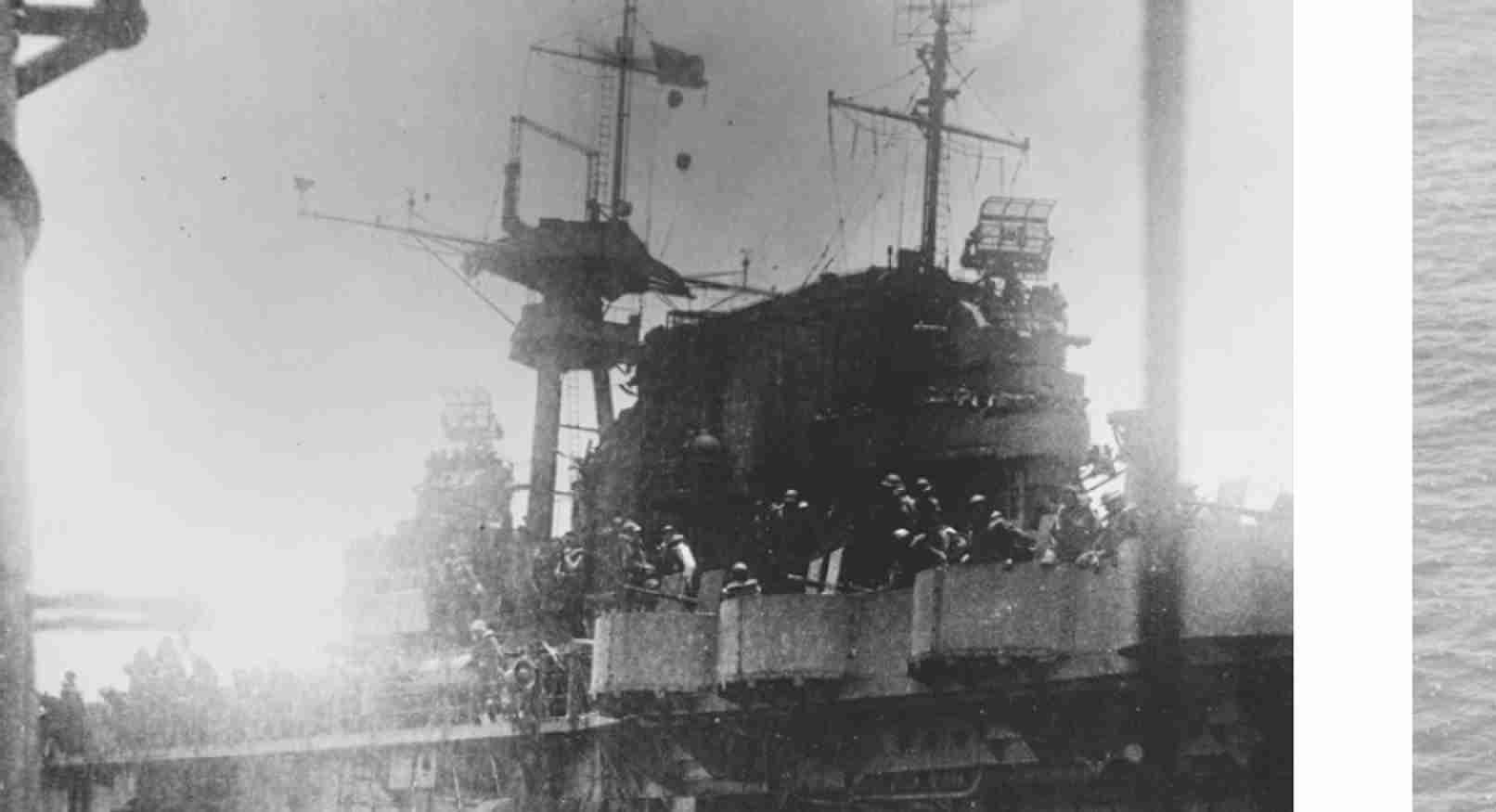

USS Hornet (CV 8) dead in the water with a destroyer alongside taking off crew following the decision to abandon ship. (Archives Branch, Naval History and Heritage Command, Washington, D.C.; 80-G-34110) (Archives Branch, Naval History and Heritage Command, Washington, D.C.; 80-G-304514)

Just after 1700, more Vals from Junyo appeared and made a run on the now-empty listing hulk that was Hornet, scoring yet another hit on the hangar deck. With Admiral Nimitz relaying to Rear Admiral Murray that radio intelligence indicated that heavy Japanese surface forces were converging on his position, Murray detailed the destroyer named for his wife’s first husband and Lloyd’s father to assure Hornet would not fall into enemy hands. Of the spread of eight torpedoes Mustin fired, three exploded against Hornet’s hull. However, the workers of Newport News Shipbuilding Company built one solid warship, and Mustin failed to observe any progress toward expediting Hornet’s plunge into the Pacific. Soon Mustin was joined by Anderson, which doubled Mustin’s score with her spread of eight fish. However, the six additional blows to Hornet’s hull still failed to flip her over. As the day receded, Japanese scout planes flew over to observe the odd scene of two American destroyers peppering one of their most prized ships with 5-inch rounds. Alerted of the potential of capturing an afloat albeit crippled American carrier, Vice Admiral Kondo’s forces accelerated, and he sent destroyers ahead to engage and chase off the two American surface ships that were attempting to foil their attempt at capture. At 2015, Mustin’s radarmen reported contacts to the west, and soon numerous contacts could be discerned. Having expended hundreds of rounds of ammunition into the dying carrier’s blazing hull, the two American tin cans exited the area at flank speed, chased by Japanese floatplanes. Twenty minutes after Mustin and Anderson departed, the burning pyre drew the Japanese destroyers Akigumo and Makikumo to close quarters. As the Japanese capital ships came over the horizon with their commanders, hopes for towing home an American carrier to impress the Emperor faded as the list on Hornet increased to 45 degrees. Concluding that the carrier was beyond salvage, Vice Admiral Kondo gave the two destroyers permission to finish her off with two Long Lance torpedoes apiece. Early on October 27, a day that had been celebrated in the United States for two decades as Navy Day, Hornet finally began her plunge to the ocean floor.21

Lloyd recalled his stepfather was a quiet person who privately remained bitter on how Hornet was abandoned as his long-time friend, Thomas Kinkaid, departed, leaving Task Force 17 with no air cover. “I think what had been a friendship for many years between those two officers was never the same thereafter.”22