G iven Japan’s mountainous nature, with forests, fields and agricultural land covering some 80 per cent of the country, 1 it’s no surprise that the nation’s urban areas are crowded. Tōkyō has a population of over 13 million, 2 with more than six thousand people per square kilometre. 3 As a result the Japanese have become masters of small-space architecture and styling.

Personal space is limited and, in recent years, clutter has become as much of a challenge for Japanese people as it has for many of us in other nations. Perhaps this is why they have become so adept at organisation and storage, why Muji (literally, ‘no label’) is a high-street favourite and why Marie Kondō is a household name. However, don’t be fooled into thinking that most Japanese people now live in tatami -matted rooms 4 devoid of stuff. They don’t. While the overall concept of minimalism has had a transformative impact for many, it can end up being another kind of perfection. It’s one more opportunity to beat yourself up for not doing something right, and frankly, it’s exhausting.

Perhaps you’re like me. You like the philosophy of minimalism and have entertained dreams of a perfectly tidy home, but found that disciplined minimalism doesn’t really work for you because you have children/pets/a hectic lifestyle/a weird fetish for antique teapots/more books than your local library or some other reason that makes you run from perfectly organised sock drawers. Or perhaps you rent and are limited in terms of how you are allowed to alter your living space. Or maybe you are on a tight budget and think that a welcoming home is for people with more disposable income. Or maybe you are just busy, and it feels like such an effort to go through everything. If any of this sounds familiar, the alternative ‘soulful simplicity’ might just be for you.

‘Soulful simplicity’ is my name for decluttering and styling your home with love, without making it clinically minimal or trying too hard. It’s a way of organising and personalising your space, which makes your home welcoming and beautiful, while still feeling lived in.

A wabi sabi lens can inspire us to embrace soulful simplicity and treasure what we already have.

There is a lovely phrase in Japanese, igokochi ga yoi

(![]() ). The kanji

5

literally mean ‘being here-heart-place-good’, and it is used to describe a feeling of comfort, of feeling at home. I like to think of it as a place for a happy heart. That’s what we want to create with soulful simplicity.

). The kanji

5

literally mean ‘being here-heart-place-good’, and it is used to describe a feeling of comfort, of feeling at home. I like to think of it as a place for a happy heart. That’s what we want to create with soulful simplicity.

Your home, your space

The spaces in which we live influence the way in which we live, and how we feel as we go about our daily lives. If we want to live differently, changing our environment, and the details of our living spaces, can play a major role in making a shift. Our homes can be sanctuaries, gathering places, repositories of love and laughter, solitude and rest. They can be grounding, comforting, inspiring and relaxing. Our homes are where our stories are written, and they have the potential to enhance our experience of the every day.

A wabi-sabi- inspired home: lived in, loved and never quite finished

The beauty of ‘soulful simplicity’ is that it can help us make any dwelling – regardless of size or budget – a lovely place to be. This comes as a relief to those of us who swoon over design magazines and lose hours on Pinterest and Instagram, but have the niggling feeling that our homes will never quite look like that. Wabi sabi reminds us that they are not supposed to look like that. Homes are for living in, and living is not a perfectly tidy affair. The good news is that the chaos of real life, edited a little, can reveal a lot. Most of us already have the makings of a welcoming space. With just a little time and attention, your home can become a sanctuary reflecting what really matters to you.

Taking inspiration from the traditional tea room – the embodiment of wabi sabi – we can envision a clean, simple, uncluttered space. It’s about deciding what to retain and what to release, what to show and what to store, what to tinker with and what to treasure.

You don’t need to wait for the perfect time – when you have the money to redecorate, when your children have left home or when you finally have time to sort every drawer and cupboard. You can begin today, right where you are. This is not a set of rules; it’s a set of ideas and questions for you to consider in order to do it your way.

The emotional connection

The truth is many of us have houses filled with clutter, even though we don’t like it. We buy stuff when we don’t need it. We tell ourselves we really should get everything in order, and then we switch on the TV instead. Over the years in my work with people trying to make major life changes, decluttering has always been a significant part of their journey. As they begin to release more and more stuff, they begin to notice the releasing of negative thought patterns, feelings of insufficiency, allegiances to busyness, attachments to past versions of themselves and desires for a life that is not connected to who they are or what they really value. This is where wabi sabi really comes in.

Soulful simplicity makes for contented sufficiency.

When you realise you are perfectly imperfect just as you are, you have less need for ‘stuff’ to boost your self-image. Ultimately, soulful simplicity in your home is about you and the experience you want to create for yourself, your family and your friends. This is about tuning into what you love and making space for authentic inspiration. It’s about what pulls you in. It’s about quality, depth and choice. And it’s about putting your judgement to one side, and focusing on what you can do with what you already have.

A wabi-sabi -inspired home is a restful space that welcomes guests and nourishes family life. It’s a place for treasured things that carry love and evoke memories, not just new things bought on impulse. There is no right or wrong. It’s unpretentious styling, done in a perfectly imperfect way.

Later in this chapter, I will introduce some tips for decluttering and soulfully simplifying your space in a wabi-sabi -inspired way. But first, let’s take a look at the notion of Japanese beauty that lies beneath it all.

Making beauty

If you were to put your nose against the glass and peer through the window of the old shed studio, you might see Makiko Hastings at her potter’s wheel, sitting on a wooden chair flecked with slip and marked with the ghostly fingerprints of an artisan at work. You’d notice her shoulders rise and fall in gentle rhythm as she ushers the clay into shape. On the shelves behind her, you’d see rows of drying pieces, each handcrafted with love and her innate sense of beauty.

I first came to know Makiko’s work seven years ago, when I bought a set of the bird-shaped chopstick rests she made to raise funds for victims of the Great East Japan Earthquake back in 2011. In all, she made over a thousand ceramic birds, to support the residents of the town of Minamisanriku which was 70 per cent destroyed by the tsunami that followed the earthquake. Makiko has had her own share of challenges over the years, but she has come out the other side with a deep appreciation for her family, and for her creativity.

These days, Makiko crafts each of her pieces with individual care, for her online shop 6 and trade customers. Asked about her aesthetic choices, she explains how simplicity in one area allows for detail in another. One example is a set of dinner plates she was recently commissioned to make for the head chef of a local restaurant. Unusually flat, they have an exquisite cobalt glaze which varies slightly from plate to plate, giving each diner a unique visual experience of their food.

Beyond her consideration of the form, decoration and colour, Makiko sees her plates as a receptacle not just for food, but also for memories. Crucially, she believes that the customer completes the beauty of each piece by using and treasuring it. And therein lies a crucial observation: Japanese beauty is discovered in the experiencing, not just the seeing.

Deconstructing Japanese beauty

There is no single agreed set of terms to define Japanese beauty, so I have curated the most popular ideas with the aim of making it easily translatable into your life. On the surface of Japanese beauty there is taste (the visual); beneath it is flavour (the experience).

Consider for a moment some of the things we might associate with beauty in Japan: the striking elegance of a maiko 7 in her sumptuous chartreuse silk kimono , paired with an intricately embroidered scarlet obi , 8 the chic look of a smart Tōkyō-ite, the artfulness of a single camellia in an ash-glazed Hagi-yaki 9 vase or the simplicity of a traditional tatami mat room. How are all these views of Japan – so different in style, colour, texture, pattern and complexity – part of the same aesthetic construct? It all comes down to taste.

The beauty on the surface

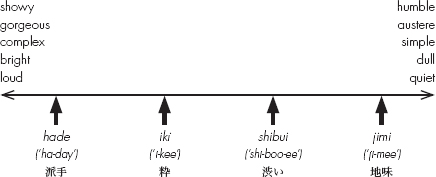

If we were to mark out the key types of Japanese taste on a spectrum it would look something like this:

|

Hade

( |

Showy, gaudy, liberal. A bright kimono , bejewelled nails, high-colour manga characters. The colours can be anything from primaries through to neon. |

|

Iki

( |

Chic, stylish, worldly and sophisticated. The appearance of being effortlessly cool (although it may have taken some effort); think sharp suits and sophisticated officewear, confident use of colour. |

|

Shibui

( |

Sometimes translated as austere, subdued, subtle or restrained, although ‘to the Japanese the word is more complex, suggesting quietness, depth, simplicity and purity’. 10 In recent times, shibui has come to mean something closer to quietly cool, well-designed, understated style. In terms of colours, it suggests dark, rich and deep, often with some neutrals and a hint of a dusty accent colour, like the palette of a hydrangea. 11 |

| Jimi ( |

Literally means ‘earth taste’ – sober, conservative, unobtrusive. Neutral, beige or dull grey tones. If patterned, a low contrast all-over plain design. |

There is a place for elegance in each of these tastes, but they look very different on the surface. They can also be used to describe attitudes.

Where does wabi sabi fit in?

For some time now the term wabi sabi has been used in the West as an adjective to describe a particular taste. It has come to represent a natural, rustic look, which honours imperfection, organic materials, textures and character. In terms of colours, think subtle shades of nature – earth tones, greens, blues, neutrals, greys, rusts. I love objects with characteristics like these. I am drawn to them, and I decorate my home with them. But they are not wabi sabi in the deep sense that we have been discussing.

My guess is that this shift in meaning happened some time ago, when some daring foreigners, intrigued by wabi sabi , sought to get to the heart of the matter. I imagine the kindly Japanese people they asked about it perhaps couldn’t find the right words, so instead they pointed to things like a simple bowl, a tea-ceremony room or a withered leaf – things they associate with the experience of wabi sabi , but that are not intrinsically so. As a result, we have come to a curious place where many of us non-Japanese are familiar with wabi sabi as a name for a particular ‘look’ that celebrates imperfection and the mark of time, rather than appreciating its powerful depths.

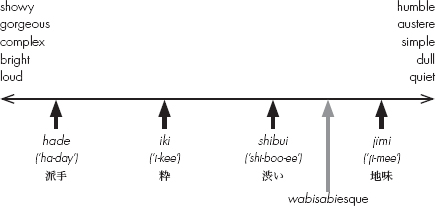

To avoid confusion, and for want of a single Japanese word, I will use the term ‘wabisabi esque’ to describe this particular kind of visual taste (on the surface), in contrast to the philosophical wabi sabi as an experience of the essence of beauty (in the depths).

Here are some of the terms most commonly used to describe the wabisabi esque look:

• Asymmetrical

• Atmospheric

• Flawed beauty

• Humble

• Imperfect

• Irregular

• Marks of the passage of time

• Modest

• Natural

• Nostalgic

• Organic

• Raw

• Restrained

• Rough

• Rustic

• Serene

• Simple

• Soulful

• Subtle

• Textured

• Understated

If we were then to add this ‘wabisabi esque’ to the taste spectrum, I think it would sit somewhere between shibui and jimi (although exactly where it sits is, of course, a matter of taste):

What is your natural style?

Take a moment to consider where your natural taste lies on this spectrum. To help you identify this, take a look around your own home, and think about the kind of spaces that inspire you. Remember, visual interest can come from texture, shape, scale and shadow, not just from colour.

• If your taste is hade or iki , wabisabi esque style can add a little calm and serenity, and help you reconnect with nature.

• If your taste is shibui , wabisabi esque style is likely a natural fit for you, if not already on your radar, and can bring a little more character and story.

• If your taste is jimi , wabisabi esque style can add a little warmth and richness.

The beauty beneath

The Japanese appreciation of beauty does not stop at the external ‘look’. Rather, there are particular words to describe the emotional quality of beauty beneath the surface, connected to our experience of that beauty. There is a host of different words to represent different aspects of this, some of which cross over in meaning with others. To keep it simple I would like to share just the most important ones here. 12

Mono no aware

(![]() )

)

The term ‘mono no aware ’ is a refined sensitivity and emotional response to time-limited beauty, and has been variously translated as ‘the pathos of things’, ‘the bittersweet poignancy of things’ and even ‘the ahhness of things’. It is the beauty in perishability. At first glance, the description may seem similar to ideas about wabi sabi , but there is one distinct difference: mono no aware focuses on the beauty (and the impending vanishing of that beauty), whereas wabi sabi draws our attention to what that beauty reminds us about life. When Japanese people use metaphors to describe each term, they will often reference the fleeting beauty of the delicate blooming pink cherry blossom just before it falls when alluding to mono no aware , but for wabi sabi they would be more likely to speak of a fallen autumn leaf.

Yūgen

(![]() )

)

The term ‘yūgen ’ refers to the depth of the world as seen with our imagination. It has been likened to the beauty of grace, of mystery and of realising we are a small part of something so much greater than ourselves. Yūgen is considered one of the most important principles of traditional Japanese Nō drama. It emerged from the highly refined culture of the Heian-era nobility 13 and has evolved over time to represent a profound sense of wonder instilled by the poetic nature of beauty.

Wabi

(![]() )

)

As we saw in Chapter 1 , wabi is the feeling generated by recognising the beauty found in simplicity. It is a sense of quiet contentment found away from the trappings of a materialistic world. The spirit of wabi is deeply connected to the idea of accepting that our true needs are quite simple, and of being humble and grateful for the beauty that already exists right where we are.

Sabi

(![]() )

)

Again, as we saw in Chapter 1 , sabi communicates a deep and tranquil beauty that emerges with the passage of time. Visually, we recognise this as the patina of age, weathering, tarnishing and signs of antiquity and, as such, it can be used to describe the appearance of a thing. But it also goes deeper than that. It is a particular beauty which respects, reflects and reminds us of the natural cycle of life, prompting a host of emotional responses, ranging from wistfulness and melancholy to pensiveness and longing.

These emotional elements of beauty are of great importance to the Japanese aesthetic sense. To appreciate them, we have to pause, pay attention, be open and tune in.

Writing about Japanese beauty in House Beautiful in 1958, then editor Elizabeth Gordon, who was in the process of a five-year-long research project preparing for two record-breaking issues on Japan, said:

First, you won’t learn to recognise beauty if you are tied to the familiar or the time-honoured way of doing something. You have to look at everything through pure eyes, which means forgetting all associations of price, age, social context, prestige, etc. Wipe away all judgements made by others and respond to the object as you do to those things in nature such as trees, sunsets, clouds and mountains. Second, you won’t learn to see beauty if you look at objects isolated from each other. Especially in objects inescapably tied to each other. Things grow or shrink in beauty depending on what environment they are seen against. 14

Inspired by Japan, one of America’s leading tastemakers at the time hereby gave her readers blanket permission to stop judging the things they put in their home by their perceived value in relation to what others thought, and rather to embrace what instinctively drew them in.

The beauty inside

Japanese beauty cannot be described, in one word, with logic. It has to be seen with the eye and the heart, participated in, experienced. The most important lesson wabi sabi teaches us for inviting more beauty into our lives and living spaces is this:

Beauty is in the heart of the beholder.

But if beauty is in the heart of the beholder what does this mean in practice for us, in terms of discovering a new way of seeing?

It means seeking out beauty with all our senses. It means pulling ourselves back from the constant pursuit of more, so we can notice what’s already in our field of vision. It means slowing down enough to look, and paying attention to what lies beneath the surface. It means surrounding ourselves with things and people and ideas we love and cherish. And it means reflecting, every now and then, about the fact that life is a cycle, not a forever, and that it’s short and precious.

It also means opening our hearts to possibility and wonder. And it means looking for the gifts of a simpler life.

![]() Senjyōjiki ni nete mo tatami ichi mai.

Even in a room of a thousand tatami

mats, you only sleep on one. Japanese proverb

Senjyōjiki ni nete mo tatami ichi mai.

Even in a room of a thousand tatami

mats, you only sleep on one. Japanese proverb

Making your home your own

Spread around me on the floor is a multitude of interior magazines and books I have collected from Japan over the years. I am trying to pinpoint exactly what it is that has long drawn me to Japanese design and style. As my eyes flit across the covers, and my hands flick through the pages, I am transported back to the early 2000s, when I was living and working in Tōkyō. I had a hectic job in the world of sport, but in my spare moments – at lunchtimes, and weekends – I would spend hours in cosy cafés, reading about architecture, interior design, ceramics, textiles and styling. Rare days off were spent visiting exhibitions and seeking out independent shops in Jiyūgaoka, Daikanyama and Kagurazaka, delighting not only in the beautifully crafted products on offer, but also in the way they were packaged and wrapped.

When considering what to do after my contract had ended, I mulled over the prospect of training as an ‘interior co-ordinator’, helping people style their homes. There was a huge boom in zakka shops. The rather dull translation of zakka as ‘miscellaneous items’ belies the delight found in zakka treasures – things that express your taste and personality, and add layers of story to your home. Many of the products in zakka shops were compact, reflecting both the Japanese love of attention to detail, and the practical reality of people living in small spaces. Around this time, I developed a slight obsession with Japanese stationery, a love that remains to this day. I also discovered the Japanese genius for home organisation and creative storage.

My tiny apartment in Ushigome-Yanagichō was tucked away in a quiet patch of residential houses, far from the nearest high-rise, which made the area feel more like a village than the middle of a thriving metropolis. The front door opened into a genkan (entranceway) where shoes would be removed before stepping up into the apartment. With the exception of a small bathroom, my place was a one-room studio. Outside the kitchen window was a small disused piece of land where mint grew like wildfire. To this day, I think of the apartment every time I smell that cool, refreshing scent.

I furnished it slowly and carefully, on a budget and within the constraints that come with such a modest space. Each item was treasured, and had a memory attached. The washi paper I used as a wall hanging had been sourced from my favourite paper shop one early spring afternoon, just as the plum blossom was falling. The linen tablemats, hand-carved chopsticks and well-loved crockery had been precious gifts from friends. I used them even when it was just me for dinner, which was most days. Books about flowers, pottery and slow living were stacked in small piles with a teapot or a vase atop, used as decorations in place of expensive objets .

Before we can beautify, we need to simplify, and make the most of the space that we have.

These days, we have so much choice, and access to so many cheap things, we usually shop, consume and grow our credit-card bills in a hurry. Our lives and our cupboards are rapidly becoming overstuffed. In recent years, as my family has grown to include two young daughters with a penchant for pink plastic and baby dolls, I have found myself returning to Japanese inspiration for ideas on bringing a sense of serenity to our home without breaking the bank.

Themes to inspire you

To come back to the commonalities between the Japanese interior books and magazines that lay scattered at my feet, I noticed several threads: simple clear spaces, texture in furnishings, carefully chosen items displayed in a way that is gentle on the eye, small things in a small place (no oversized furniture, for example), more put away than on display, nature indoors (from a tiny courtyard garden to flowers and found objects displayed inside) and a sense of the seasons, shadows and light, lots of neutrals, flexibility in the way the space is used and an underlying sense of calm.

There was also often a detail that invited a sense of wonder. A single bloom in a tiny vase. A partly hidden view, suggesting, but not telling. This made me think about how we could benefit from not putting all our treasures on display, not cramming every spare inch with stuff, not telling our whole life story on first meeting or rushing to fill all the pauses in a conversation.

I have gathered these threads into five themes for you to explore in your own life. They are: simplicity, space, flexibility, nature and details. 15

Simplicity

One Japanese lifestyle brand I have admired for years is ‘fog linen work’, 16 founded by designer and entrepreneur Yumiko Sekine over two decades ago. Her store, tucked away on a small street in the trendy Shimo-Kitazawa district of Tōkyō, is a serene oasis in the bustling capital. Exposed concrete walls are a textured, yet neutral backdrop for wide open shelves, which hold linen napkins in wire baskets, small stacks of wooden plates and open trays with tiny buttons. Linen clothing and bags in subtle colours are spread out on a long rail. My favourite items are the heavy-duty aprons, which make you want to go straight home and cook something. There is a sense of space, and of time stopping inside the store.

Sekine-san has had years of exposure to the West, having imported lifestyle goods from the USA before she set up ‘fog’, and now working primarily with Lithuanian suppliers to manufacture the linen goods she designs herself. This makes her style choices even more accessible, as they seem just as at home in a San Francisco apartment or London town house as in a Japanese abode.

When asked to share a few words about her particular style she told me:

It’s simple, minimal, organised. My European distributor tells me there is something distinctly Japanese about the way I display our products. I like calm neutrals, and I sometimes use accent colours for our clothes, depending on the season. My aim is to make quiet products that can ease themselves into people’s lives and homes, bringing a subtle sense of calm. I like to live with natural materials, such as linen, cotton, wood and some metal. No plastic. This suits my personality, and my love of simple things.

Every time I go to Sekine-san ’s store it inspires me to make my own shelves more open, to pare back and display only things I really love. When we stop using shelves just for storage, and instead see them as holders of treasures, the difference is remarkable. Instead of a room closing in on you, it seems to open up.

On my return from Tōkyō this time, I hung my linen apron on a hook where I could see it, made a simple display of cookbooks paired with vintage bottles and old photos on the windowsill, shook out a favourite tablecloth and popped some wildflowers in a vase to go in the centre of the table. It took a couple of minutes and cost me nothing. Instantly, I wanted to be in the kitchen, making something delicious for my little family.

Top tips for decluttering

It is well documented that decluttering our spaces can help declutter our minds, not to mention save us time and money. Try it in your own home with these simple tips:

1. First, taking inspiration from the household-organisation guru Marie Kondō, 17 make a list of the main categories of ‘stuff’ in your home, such as books or toys. Then, pick a category and gather like things together from all around the house. Select only what you need or truly love, and then get rid of the rest (sell, recycle, donate). This can be fairly daunting if you have stuff spread all over your house, but in the end it means you are making decisions based on all the facts. When you realise you have five sun hats but only go somewhere hot once a year, it suddenly becomes easier to let go of excess stuff. When putting the remaining items away, try to keep like things together, so you can easily retrieve them.

2. Consider what you can replace or eliminate with technology – for example, using music apps instead of buying physical recordings, printing and framing a few special photos and storing the rest digitally, or perhaps using ereaders and the local library for all but your favourite books.

3. Consider what you can store in your memory, instead of in your cupboards. For example, if a distant relative passed away and you received a box full of items connected with them, choose one thing to keep as a reminder, and then release the rest.

4. Gather up your paper mountain, and sort it into three piles: a) To Action; b) To File; and c) To Bin. With pile a) To Action, set aside an afternoon where you action every single item. No excuses. With pile b) To File, where possible scan and digitally store and back up your documents, and then shred the originals, keeping only what is required by law, such as home-ownership documents. With pile c) To Bin, shred anything private and recycle the rest. Then choose one place where you will put all pending paper from now on, and make a weekly appointment with yourself to action, file or bin.

5. One dropped piece of clothing, unfiled letter or dumped toy is a magnet for others. Bring in a simple system for easy tidiness.

6. Involve those you live with. Make it a game.

7. Don’t forget to declutter your handbag or wallet. It’s a space you probably view more times in a day than most of the rooms in your house.

Space

Although the average Japanese person does not live in an architect-designed home, there are valuable lessons to be learned from the principles of Japanese architecture to inspire our own spaces. To discover more about these, I sought out Dr Teruaki Matsuzaki, one of Japan’s foremost architectural historians, who outlined the main characteristics of Japanese architecture as follows:

•

Ma

(![]() , space)

18

, space)

18

• Nature and the connection between inside and outside

• A sense of beauty

• An understanding of light and shadow

• The careful selection of materials (quality, source, texture, smell)

• The concept of ‘less is more’

Reiterating Makiko’s feelings about her pottery clients playing a role in the beauty of her products, Matsuzaki-sensei said that the key to aesthetic genius is leaving something unfinished to draw the viewer in. Beautiful writing leaves something unsaid, so the reader can finish it in their imagination. Beautiful art leaves something unexplained, so the viewer participates with their curiosity. It’s the same with architecture and interiors. Perfection and completeness are not the ideal, even if architecture appears ‘perfect’ in design magazines. Matsuzaki-sensei said, ‘Spaces are ultimately created to be lived in and used, and if they don’t do that well, they are not considered successful.’

What can we take from this for our own homes? We can create space. We can bring nature in. We can decide what we consider to be beautiful and integrate that. We can be aware not just of light, but also of shadow. We can choose the materials we use carefully, and we can make choices that leave us living with what we really love.

The satisfaction of early results breeds enthusiasm so I’m a big believer in first tackling what you most often see. First, declutter main items (books, clothes, toys, files, etc.), using the tips in this chapter. Then try some of these ideas in one room at a time, in your home or workspace:

1. Clear everything from the floor.

2. Clear everything from the surfaces.

3. Clear everything from the walls

4. Now add back in slowly, asking yourself the following questions:

• How do I want to feel when I am in this room? What colour palette will help me feel that way? (Consider the spectrum of taste shared in this chapter, and how wabisabi esque style and colours could bring a sense of calm, warmth and character to the room.)

• What do I like about this emptier space? Which aspects of it would I like to keep clear? (If you feel like repainting, now is a good time.)

• What could I do differently on the walls? What would be special? What has meaning or memory? (Examples of interesting things to frame include maps, postcards, inspiring words, children’s art, your art, posters, a tea towel or scarf, a sheet of beautiful wrapping paper, dried flowers.)

• How can I arrange the furniture to make best use of the space? Is this the right furniture for the room? (Now might be a good time to sell something that doesn’t work for you, and visit a flea market, antique shop or independent furniture maker for ideas for a replacement, or try upcycling something yourself.)

• What particular items do I already own that can bring beauty into this room? What adds a sense of story? What can I repurpose? Add these back in slowly, in small groups for interest.

• How can I bring nature into this room, and introduce more natural materials? How can I reflect the season?

• How can I bring in texture (with fabric, paper, rough finishes, for example) on the walls, the furniture, the floor, the ceiling?

• If you enjoy books, how can you include them as display items? (On shelves, stacked to make a side table, three high with something on top to make a small arrangement, for example.)

5. Now look at all the other objects you removed from the room, which you have chosen not to put back. Use the tips in this chapter to declutter and sort them.

6. Make a note in your diary to swap things around and refresh this room once every season, or monthly if you prefer.

7. When you’re ready, enjoy a cuppa in your beautiful space, then move on to the next room!

Flexibility

For those people who live in more traditional Japanese dwellings, usually in the suburbs or rural areas, their homes tend to be made primarily of wood. Walls are thin, and often flexible to allow for best use of space. Tatami -matted rooms are often multi-purpose, transitioning from a relaxation space, to a meditation space, to an eating space to a sleeping space. You can move doors and tables, lay the futon out or put it away, host people or retreat from them.

To find out more about this idea of flexibility, I spent some time in the home of my friend Daisuke Sanada, CEO of Suwa Architects and Designers. Son of a carpenter himself, Sanada-san built his home with a little help from several carpenter friends, in a small town on the outskirts of Tōkyō. He lives with his wife, Sayaka, who is an interior designer, and their family, in a compact, well-thought-out, beautiful space.

Sanada-san , who is descended from a famous samurai warrior, has a strong sense of tradition and vast knowledge of his country’s heritage. He brings this to his work, along with a contemporary eye and a love of cosy spaces, which help strengthen the bonds of the people living in them.

His own home is over two storeys, the front part double height with a carefully hand-crafted pitched cedar roof and a huge triangular window at one end, which makes the trees outside feel like they are part of the house. This open area houses the living, dining and cooking spaces, with a raised section of tatami alongside a wood-fired stove creating the perfect place for his dog to curl up, for doing some morning yoga or for catching a nap on a winter’s afternoon. A simple wooden sideboard plays host to a relaxed display of crumbling Yayoi period pots dug up in his friend’s rice field. In the region of two thousand years old, they have been repurposed as simple vases and brought into the Sanada family’s daily life to enjoy, rather than being stored away like museum pieces.

At the back of the ground floor are a bathroom, bedroom and storage room, and a ladder leading up to the chill-out area and further sleeping space on the mezzanine above. This upper section is divided up using flexible furniture, such as moveable bookcases and fabric curtains hung from the roof, to allow for privacy or company, depending on the day. The result is a welcoming home that supports the lifestyle Sanada-san and his family want. It is stylish, yet practical, and soulfully simple.

Sanada-san and I spent many hours talking about the value of contrast and relationship in Japanese life: how beauty is found in the existence of tension; light and shadow; sound and silence; simplicity and detail; sublime and ordinary; presence and absence; freedom and restraint; wabi and sabi . We talked about how beauty often arises in the middle of things – a conversation, a lifetime, a walk in the woods. And how everything is connected – everything within a space, the inside and the outside, our surroundings and our minds, in our relationships with each other and ourselves in the web of nature.

Those of us who do not live in Japanese-style homes can still be inspired by these ideas. We can divide up our spaces with the placement of our furniture, rugs and shelving, and move things around regularly, depending on how we want to use the space, acknowledging that it is never ‘finished’ and we aren’t aiming for perfection. We can repaint walls, swap out displays, bring in some seasonal flowers and plants, and refresh whenever the mood arises. We can pay attention to the visual contrasts, and the relationships between what we see and how we feel. A window is not just a window – it is a frame for all that lies beyond it. A shelf on one side of the room may be a balance for something on the other. Notice how individual things in a room affect others, and how things work together, with the space, the flow, how you live and how it makes you feel.

Remember: utility, simplicity, beauty, story.

How can you look at the spiralling excess and waste, and the poisonous culture of comparison, and decide to do things differently? How can you be quietly radical like Sen no Rikyū (see p. 13 )? How can you be an advocate for something that feels more real?

The most soulful shopping of all is that which costs nothing, and only inflates what you own with natural beauty. Try spending time in nature, collecting gifts from the forest, or creating with your hands instead of buying.

When you are considering buying something new, ask yourself these questions:

• Do I really need it? Do I already own something that can do the job? Am I actually going to use it?

• Do I love it? Will I still want it twenty-four hours from now? A year from now? There is a beauty in longing. Can I wait a while for it, to make sure I really want it?

• Does it serve the season of life I am in right now (or in buying it, am I trying to hold on to the past or pressuring myself into a particular version of my life in the future)?

• Does it work with the other things I own?

• Will it help me use my space more flexibly?

• Is this something I could get for free by borrowing or trading?

• What am I willing to get rid of to make space for this?

• What will I have to sacrifice to pay for this? Is it worth it?

• Is it made of natural materials? If not, is there a version that is?

• Is it worth paying a little more to get a version that will last?

Nature

Nature is an essential element of a wabi-sabi -inspired home, as it connects to the deepest part of the whole wabi sabi philosophy, reminding us of the transient nature of life. We will explore nature and the seasons in detail in Chapter 3 . For now, consider how you can bring more natural materials into your home. For example, wood with a rough grain, bamboo, clay, stone, dull metals, handmade paper or textures woven from natural fibres. One of my favourite treasures is the old wooden rice bucket we use for storing firewood. Be creative with your ideas. Upcycle. Repurpose. Spend time at flea markets and in vintage and antique shops. Age often adds depth and beauty to natural materials, so don’t assume you have to buy new.

Spontaneity is to be encouraged. I often mix up potted herbs and bottles of oil in the metal containers hanging in my kitchen. I might use washi tape (low-tack masking tape made from Japanese paper) to stick some fallen nature treasures onto the wall, or put up a makeshift collage of photos alongside my children’s bark rubbings and leaf prints.

Cut flowers can brighten up a space. Try leaving them a little longer than their peak, and notice the beauty in their fading. It can also be refreshing to embrace a little wildness, using wildflowers and found objects. Even pretty weeds. Go outside and take a look at what nature is offering you in this particular season. What gifts from the forest, or wood, or hedgerow or beach could you bring back into your home? Fallen leaves, berries, conkers, acorns, seed pods, shells, driftwood and feathers all carry the spirit of nature and of wabi sabi .

Try incorporating some of these natural items into grouped displays in corners of your home, perhaps paired with a favourite book and some old glasses, or your vintage typewriter and a stack of old ribbon. A sprig of winter berries in a small jug. A handful of snowdrops from your own garden. A string of fairy lights on a fallen branch.

Details

Attention to detail is something you notice everywhere in Japan. In cafés, in shops, in homes, in temples and shrines, even in public spaces, someone has taken care to add a small detail. These details add to the interest of a space, and can really make it yours.

We have a double-height window on our staircase, which used to have long, heavy curtains. They were there when we moved in, and I was loath to remove them because they looked like they had cost the previous owners a lot of money, and to take them down would be a waste. But I went up and down those stairs several times a day, and every time I passed the curtains I felt a little bit resentful. In the end, I realised I was being ridiculous. It was our house now, and we could use it however we wanted. So I took the curtains down.

Instantly, the hallway was flooded with natural light. In time, I would discover that at other times of day, the windows would throw interesting shadows onto the landing. Now we could see the deep, wide windowsill, I unwrapped an old, mottled ceramic sake bottle, gifted from a friend when I left Japan, and repurposed it as a vase with a single flower from the garden. Next to it I set out pebbles from the beach, treasure hunted by small hands on a windy day, and I finished it off with a simple postcard which said, ‘There is a lot of beauty in ordinary things.’

My little arrangement sits on the right-hand side of the windowsill, with empty space on the left. Every now and then, I’ll swap out the flower and the postcard, pile up the stones or move them around. It is my kind of beautiful and offers a moment of stillness every time I go up or down the stairs.

Where could you create pockets of serenity and beauty around your home?

Below is a summary of my ten key principles for a wabi-sabi- inspired home. While wabisabi esque objects have a role to play, they are not the full picture. The philosophy of wabi sabi is the guide here. It’s perfectly fine for your home to be a work in progress. Real life is not like design magazines. A home is to be lived in, so there’s no need to wait until everything is finished before you invite your friends round to enjoy time together.

1. Make the most of your entranceway, which is called a genkan in Japan. Tidy out-of-season coats away. Put out some flowers. Invite visitors to leave their shoes at the door, Japan-style (and try to encourage anyone who lives with you to make it a habit). Stack shoes on shelves or in a shoebox, or perhaps under the stairs. You might want to offer guests house slippers if the floor is cold. This keeps everywhere cleaner, and gives an immediate sense of comfort and familiarity.

2. Decluttering saves you time and money, and makes space to appreciate the things you really love. However, stark minimalism is another kind of perfection. Go for soulful simplicity instead. Think clean, uncluttered and welcoming.

3. Experiment with natural matte materials like wood, clay and stone in your home, and natural fabrics for bedlinen, clothing and kitchenware. See how these bring a sense of character and calm. The eye and the imagination love imperfection, asymmetry and non-uniform surfaces.

4. Consider how you can bring actual nature into your space, with flowers, branches, seed pods, feathers, leaves, shells, pebbles, handmade wreaths, woven baskets and so on. Discover the joy of finding and styling these yourself, creating visual poetry with the gifts of the land and sea.

5. Keep both light and shadow in mind, noting how the contrast changes your space at different times of day. Embrace low light and darkness when it suits the season and your mood.

6. Consider all the five senses in your space. This depends on where you live and the kind of space you have, but it can include anything from opening a window for the breeze to using textured fabrics on your furniture, from diffusing essential oils to playing calming music. You can even consider the sense of taste, such as using fruit and vegetables within your simple displays, or adding details to make your breakfast table feel extra special.

7. Curate things you really treasure to decorate your space and nurture it with story and memory. Think about contrasts: past and present, grounding and inspiring, ordinary and special. Where possible, be creative with what you have, or repurpose items that have had a previous life.

8. Think about the importance of relationship and visual harmony. How do things look and feel in relation to other things in the room and the space itself. What is framed by your windows and internal doorways? What is on full view and what is partly hidden, hinting at something else beyond? What different textures are bringing character and warmth to the space?

9. Create tiny corners of beauty in unexpected places. A small vase on a windowsill. A handwritten note in the bathroom. A framed photograph under the stairs.

10. Notice how you need to use the space differently depending on the season of the year, and the season of your life.

Sharing your space

Writing in the nineteenth century, Lafcadio Hearn 19 famously said about Japan: ‘The commonest incidents of everyday life are transfigured by a courtesy at once so artless and faultless that it appears to spring directly from the heart, without any teaching.’ 20 This attention to the moment and the recipient’s needs is at the heart of omotenashi , Japanese hospitality.

If you have ever spent time at a Japanese ryokan (traditional inn) you will know that the sense of deep relaxation comes not just from the healing waters of the cedar bath, or the cosy warmth of your futon , but from the bowing and quiet attentiveness, and the delicate care wrapped in the phrase goyukkuri dōzo (‘Please, take your time’).

Ichi-go ichi-e

(![]() ) is a well-loved phrase that often appears on hanging calligraphy scrolls in the alcoves of

tea-ceremony rooms. It means ‘this meeting, this time only’ and is used to remind people to treasure this particular experience as it will never be repeated. If someone hosts you at their home in Japan, however casual the event, you will likely feel incredibly well looked after. This warmhearted and sincere hospitality is not just displayed in the food and drink you are offered but in the warmth of the welcome, the attention to detail and the presence of the host. Your host might say, ‘Dōzo, omeshiagari kudasai

’ (a polite way to say ‘Please begin’), and you might respond with a bow and the word ‘Itadakimasu

’, (meaning ‘I humbly receive this with deep appreciation’). This ritual is a lovely way to begin a shared meal.

) is a well-loved phrase that often appears on hanging calligraphy scrolls in the alcoves of

tea-ceremony rooms. It means ‘this meeting, this time only’ and is used to remind people to treasure this particular experience as it will never be repeated. If someone hosts you at their home in Japan, however casual the event, you will likely feel incredibly well looked after. This warmhearted and sincere hospitality is not just displayed in the food and drink you are offered but in the warmth of the welcome, the attention to detail and the presence of the host. Your host might say, ‘Dōzo, omeshiagari kudasai

’ (a polite way to say ‘Please begin’), and you might respond with a bow and the word ‘Itadakimasu

’, (meaning ‘I humbly receive this with deep appreciation’). This ritual is a lovely way to begin a shared meal.

Wabi-sabi -inspired hospitality is not about having a perfectly tidy house, all designer furniture or perfectly well-behaved children. It’s about sharing your home in a relaxed, thoughtful way, and being sensitive to your guests. Having said that, we must not forget that the embodiment of wabi sabi is the tea house, which is often modest, unassuming, spotlessly clean and bare other than for what has been prepared for the guests. This reminds us to make our spaces clean, uncluttered and welcoming, as far as is possible within the context of our daily lives.

Think of the kind of words used to describe the visual wabisabi esque – natural, humble, understated. These are the opposite of slaving over a hot stove all night to deliver the perfect gourmet six-course dinner to impress your friends, panicking when you burn the main dish and obsessing about the fact you forgot to make a dressing, while missing out on the real conversation.

Pay attention to small details to make your guests feel at home – their favourite drink, fresh flowers on the table, your treasured heirloom tablecloth, something nourishing to eat, cosy slippers, a blanket for stargazing on a chilly night. What really matters is paying attention, lending your ears and sharing the moment.

WAHI-SABI

-INSPIRED WISDOM

WAHI-SABI

-INSPIRED WISDOM

FOR SIMPLIFYING AND BEAUTIFYING

• Beauty is in the heart of the beholder.

• When you realise you are perfectly imperfect already, you have less need for things to boost your self-image.

• Soulful simplicity is a source of delight.

In a notebook, jot down some thoughts about the following:

• How does your physical space make you feel? What is your favourite thing about it? What would you like to change?

• What kind of objects do you own more of than you need?

• What accumulation habits do you have? What life habits might these be reflecting?

• What kind of items do you own that you treasure, and could use more in your daily life?

• What particular aspects of Japanese beauty and soulful simplicity inspire you? How could you bring these ideas into your own space?

• If you could let go of one thing in your life (material or otherwise), what would it be? What difference might that make? How could a deeper awareness of beauty and soulful simplicity support you in letting that go?

• What else in your life would you like to simplify?

• What is it that you really need?