Chapter 2

Jinx usually lived in the farmhouse kitchen, but of course with the Beans away in Europe, there was nobody to open the door and let him in and out, so he had moved down into the barn for the summer. When he got home, he fixed up a bed for Little Weedly in the box stall, and then, while Freddy went down to Centerboro to see the sheriff, he wandered over toward the house to see what he could find out about the newcomers.

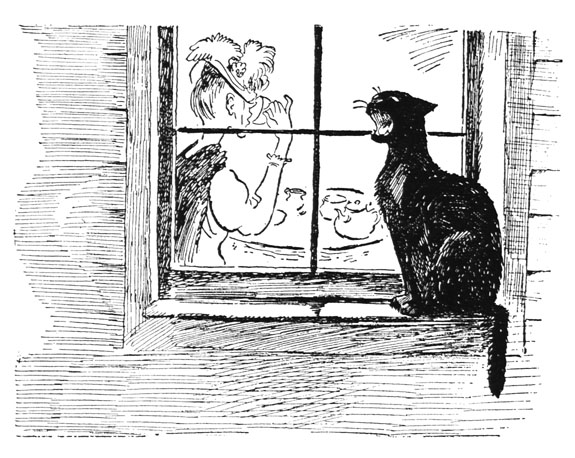

The house was shut up tight, but there was a light in the parlor window. Jinx mewed at the door to get in, and then he jumped up on the sill and mewed at the window. He could see a tall bony woman sitting at the table drinking a cup of tea. She had a black silk shawl around her shoulders and a funny old-fashioned bonnet on her head, and when she lifted the teacup she held her little finger out straight. Jinx had used his saddest and most mournful mew. It made you think of little children crying and cats dying of starvation and all sorts of sorrowful things, and you would be pretty hard-hearted if you could keep from going to the door. But the woman didn’t even look up. So Jinx made the mew even more heart-rending until you would think that he had the most awful stomachache that any cat ever had.

And at last the woman got up. She came and opened the window and said: “Scat! Stop that caterwauling before I take the broomstick to you.”

So Jinx jumped down. He was pretty mad. “Keep me out of my own house, will you?” he said. “Well, we’ll see about this.” He went around to the front door. Standing on his hind legs, he was just able to reach the bell. He put his paw on it and kept it on until he heard footsteps. Then he stepped to one side as the door opened.

A little man with a bald head opened the door wide. “Good evening, sir or madam, as the case may be,” he said, bowing very low. Then he straightened up. “Eh!” he said in surprise. “Not a soul here! Dearie me and welladay, not a single, solitary soul.” He walked out and looked around and Jinx slipped inside.

The woman had her back to Jinx when he came into the parlor, and he went under the sofa. In a minute the man came in.

“Well now, there’s a funny thing, Effie,” he said. “Doorbell rings and nobody there, nobody, not anybody at all. What a thing, eh? Eh? That was queer, wasn’t it?”

“You talk too much, Snedeker,” she said. “It was probably just neighborhood boys, playing tricks. Just let me catch them once, and there’ll be no more of that.” And she crooked her little finger genteelly as she took a small sip of tea.

“Eh, eh, all very well,” said the man. “But there’s no neighborhood around here. Can’t be neighborhood boys if there isn’t any neighborhood. Eh, Effie?”

“Where there’s people, there’s a neighborhood,” said the woman, “and where there’s a neighborhood, there’s boys, and where there’s boys, there’s mischief. Don’t bother your head about them, but go do as I told you to.” But whatever it was she had told him to do, Jinx didn’t find out, for at that minute the doorbell rang again.

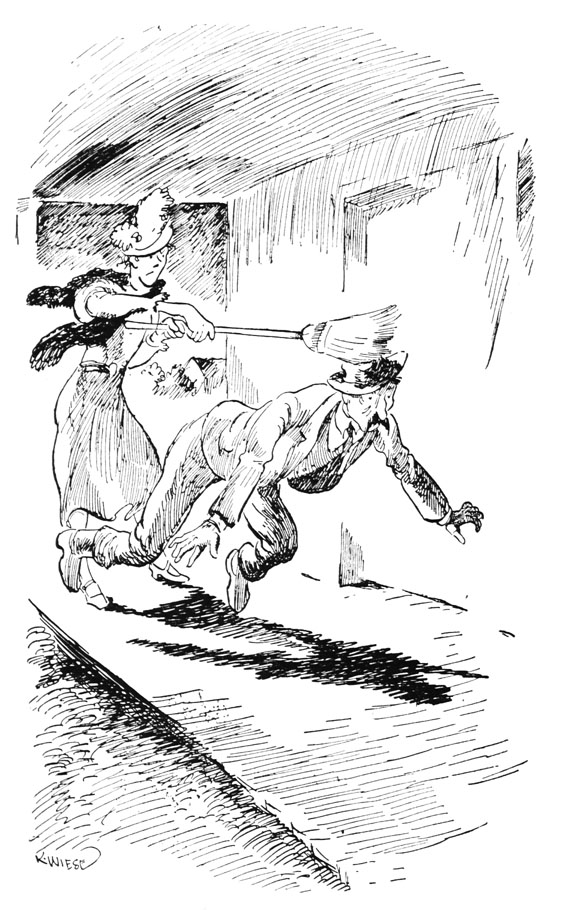

“You stay here, Snedeker,” said the woman, getting up. “I’ll see to it this time.” She took a broom from the corner and went as quietly as she could out through the back door. After a minute of silence there was a loud thwack! and a yell, and then a sound of excited voices and the front door opened and in came the woman, followed by a tall man with long drooping moustaches and a silver star pinned to his vest.

—there was a loud thwack!

“Well, ma’am,” said the tall man, “to hit the sheriff of this county with a broom when in pursuance of his duty ain’t no way to prove to him that you’re law-abiding citizens. These here premises belong to Mr. Bean, and what I want to know is: why do I find you occupying said premises, and what’s to hinder my chargin’ you with unlawfully entering same, and takin’ you down to the Centerboro jail?”

The sheriff didn’t always talk this way, but he knew that the language of the law is pretty terrifying to most people, and so he used it when he wanted to impress anybody. Besides, he had just been hit behind with a broom.

“Why, sheriff,” said the woman, with a sour smile, “that was a bad mistake on my part, and I admit it freely. But some boys have been ringing the doorbell tonight, and then running off, and when you rang I thought it was them again. I’m very sorry, and won’t you have a cup of tea?”

“One thing at a time,” said the sheriff. “Are you occupyin’ these premises with Mr. Bean’s knowledge and consent?”

“Why, I’m Mr. Bean’s Aunt Effie—Mrs. Snedeker. We’ve come all the way from Orenville, Ohio, to pay the Beans a visit. We didn’t know they were away. But now we’re here—well, we’d made all our arrangements to be away, and so we thought we might as well stay a while. Snedeker, show the sheriff William’s letter.”

Mr. Snedeker began feeling in all his pockets. From one he pulled out a ball of string and a pipe and a small bottle of cough medicine and a candle end, and from another he produced a driver’s license and some matches and a china duck and two lollipops, and from a third two watches and a screw driver and—

“Come, come, Snedeker,” said Aunt Effie, “the sheriff doesn’t want to decorate a Christmas tree; he wants to see the letter.”

“Got it somewhere,” said Mr. Snedeker, beginning on another pocket. “Eh, Effie, here’s that darning egg you were looking for last week. That’s funny, eh? And a picture of Niagara Falls—Eh, here it is, here it is.” And he handed the sheriff a letter.

“It’s Mr. Bean’s handwriting, all right,” said the sheriff. “‘My dear aunt,’” he read. “‘I hope this finds you as it leaves me, in good health and spirits.’ H’m, he spelt ‘spirits’ wrong, but I guess that’s no harm. H’m, h’m. ‘If you pass by this way going to Albany, we will be glad to have you stop for dinner.’ Well now, ma’am,” said the sheriff, “that ain’t exactly an invitation to come for a long visit.”

“Oh, you know how William is,” said Aunt Effie. “He never says more than a quarter of what he means. Why look how he signs the letter. Anybody else would sign: ‘Your affectionate nephew.’ But he just signs: ‘Respectfully, William Bean.’”

“Yes, that’s true,” said the sheriff. “What’s the meaning of this postscript—something about a silver teapot—”

“Oh, nothing,” said Aunt Effie, picking the letter quickly out of the sheriff’s hand. “Just some family business.”

“Well, it seems to be all in order,” said the sheriff. “You understand, ma’am, it was my duty to investigate.”

“Certainly, sheriff, certainly. And now won’t you have a cup of tea?”

“Afraid I must be getting back,” the sheriff replied. “I just remembered I left the jail locked.”

“Left it locked!” said Mr. Snedeker. “Well, that’s all right, ain’t it, eh? Prisoners can’t get out.”

“They can’t get in,” said the sheriff. “Most of ’em are out visiting their families tonight or at the movies, and they’re going to be good and sore if they come back and find they can’t get in.”

“Sounds like a pretty nice jail,” said Aunt Effie.

“It is a nice jail, if I do say so,” said the sheriff. “One of the most popular jails in the state. I have to make it nice, or I wouldn’t have any job. You see, ma’am, we don’t have any crime in Centerboro, and if I didn’t keep a nice comfortable jail that people want to stay in, why I wouldn’t get any prisoners to look after, and where’d my job be? So I got the cells all fixed up with good beds, and we got a game room and tennis courts and so on, and we set a better table than the hotel does. Folks like to stay in my jail, so now and then they break a few unimportant laws so they can get sent there. I don’t say it’s right of ’em, but it’s reasonable.”

“Well, I’m glad there’s no crime in Centerboro,” said Aunt Effie, “but how about these boys that were ringing the doorbell just now?”

“There aren’t any boys around here, ma’am,” said the sheriff. “My guess is, it was some of the animals on this farm. I expect you’ve heard about Mr. Bean’s animals?”

“I’ve read about them in the papers,” said Aunt Effie. “Smart enough animals, I suppose, but that’s one reason we thought we’d stay here for a while. I can’t understand William going away and leaving them all alone here. We are going to stay and look after them.”

“Well, I don’t know,” said the sheriff. “Mr. Bean knew what he was doing all right, when he left them to run the place. I guess you haven’t talked to any of ’em yet, have you, ma’am?”

“Talked to ’em, eh?” said Mr. Snedeker with a giggle. “That’s a good one, that is.” And Aunt Effie said: “Do I look like the kind of woman who’d go around talking to animals? Oh, I know,” she said: “there was a lot in the newspapers about how they can talk and about how they had the first animal bank in the country, and so on. Folderol and fiddlesticks! Don’t you try to fill us up with that kind of nonsense, sheriff.”

“I can’t make you believe it if you don’t want to,” said the sheriff. “But if I were you—”

“If I were you, sheriff,” interrupted Aunt Effie, “I’d stop talking foolishness.”

“Have it your own way,” said the sheriff stiffly. “But if you want to stay here, you’d better make friends with them—that’s all I have to say. Good evening, ma’am. And to you, sir.” And he went out.

“Eh, well, suppose there’s something in it, Effie?” said Mr. Snedeker. “Animals talking? Could be, you know. Parrots talk—why not animals? Eh, Effie?”

“Well, there’s one thing certain,” said his wife, “nobody ever said you couldn’t talk, Snedeker. Why don’t you go up in the attic and look for that teapot?”

“I will, Effie, I will. Only I’d like to ask you if you meant what you said to the sheriff about staying here for a while, eh? I thought you said we’d start back to Orenville as soon as you got the teapot.”

“And so we will. But it may take some time to find it. You may be sure William has got it hidden away in a safe place. And while we’re staying here, we’re going to see that this farm is properly run. It’s a sin and a shame for them to go off and leave everything to rack and ruin. Leaving the animals to run the place, indeed! I never heard such nonsense!”

Jinx, who had been listening all the time under the couch, was doing some hard thinking. He knew something about that silver teapot. Mrs. Bean prized it very highly and only used it on special occasions, and once when she had been polishing it with one of Mr. Bean’s old flannel nightcaps, which she saved for that purpose, he had heard her tell Mr. Bean that she would have felt pretty badly if he had given the teapot to his Aunt Effie.

“Couldn’t give it to her,” Mr. Bean had said. “ ’Twasn’t mine to give. My grandmother gave it to me, and told me to keep it for my wife.”

“Which you did, Mr. B,” said Mrs. Bean. “And yet I feel sort of sorry for her, too, not having it. She wanted it so much, and she does so love tea parties.”

“Tea parties, tea parties!” Mr. Bean grumbled. “Seemingly that’s all they do out in Ohio is give tea parties.”

“No harm in that,” said Mrs. Bean. “I expect we’d give ’em too if we had anybody to give ’em to.” She held the teapot up so that it glittered in the sunlight that came through the kitchen window. “It’s a pretty piece of silver. And yet, you know, if she’d asked us nicely for it, instead of acting as if we’d stolen it from her, I’m not sure I wouldn’t have given it to her. I suppose you’ll say I’m too softhearted.”

“No harm in that either,” said Mr. Bean gruffly, and patted her on the shoulder as he went out toward the barn. But in a minute he came back and poked his head in the door. “As long as you don’t give way to it,” he said, with the little grumble that was what he used for a laugh. And Mrs. Bean laughed too and put the teapot away.

So Jinx knew that the Snedekers must not be allowed to get that teapot. He also knew where it was, for he had been with. Mrs. Bean when, before she left for Europe, she had wrapped it in a flannel petticoat and put it in the bottom of an old horsehide trunk in the attic.

He slipped out from under the couch and ran upstairs. But the attic door was closed. He thought a minute and then went into the spare bedroom. “Hey! Webb!” he said in a cautious whisper. And in about half a minute he felt a tickling on his left ear and a tiny voice said: “Hi, Jinx! What’s on your mind?”

Mr. Webb was a spider who usually lived out in the cowbarn. But before the Beans had gone away, Mrs. Bean had been worried about flies getting into the house, and especially into the spare bedroom, so Mr. and Mrs. Webb had moved in there and had built their fly traps in every corner of the room. As a matter of fact, no flies had come in, and the Webbs couldn’t catch enough of them to make a living. But they kept on living there just the same because they knew it would please Mrs. Bean, and Mr. Webb went down to the cowbarn every day, just as a man would go to his office, and caught enough flies to keep them going. This was really pretty nice of Mr. Webb, for though you or I could have gone from the house to the cowbarn in a couple of minutes, it was a long weary tramp for a spider, particularly at the end of the day when he was tired out hunting.

“Careful, Webb,” said Jinx. “Don’t get on my nose and make me sneeze, or those people will hear me. Have they been up here?”

“Turning the house upside down ever since they got here,” said Mr. Webb. “I heard the woman say she was Mr. Bean’s aunt. She doesn’t look like him.”

“How can you tell whether she does or not?” said Jinx. “With all those whiskers.”

“Whiskers?” said Mr. Webb. “I didn’t notice she had whiskers.”

“I mean Mr. Bean’s whiskers,” said the cat. “He’s got so many that nobody has ever seen what he really looks like, so how would you know whether his aunt looked like him or not? But anyway,” he said, “we’ve got to do something about it.” And he explained.

Mr. Webb didn’t say anything for a time. He paced up and down between Jinx’s ears, deep in thought. At last he said: “If we can keep them from finding the teapot tonight before they go to bed, then before morning we can get word to the other animals, and they’ll have to do something. But in the meantime, we’ve got to keep Uncle Snedeker from finding it if he goes up in the attic. Listen; that sounds like him coming now. You follow him up if you can, and try to scare him. There’s a crack over the window where Mrs. Webb and I can get up there. We’ll do what we can. So long; I’d better hurry.”

Jinx could hear feet coming up the stairs. In a minute he saw Uncle Snedeker, with a candle in his hand, walk along the hall and open the door to the attic stairs. Jinx followed him and when Uncle Snedeker held up the candle to look around, the cat darted behind an old chest of drawers.

Mrs. Bean was a good housekeeper. Everything in the attic was piled up and packed away neatly. The floor was swept, and there were even clean little muslin curtains at the windows. “Neat as a new pin,” said Uncle Snedeker. “Let’s see, now, Snedeker; where’ll you begin, eh? Where’ll you start? That big chest in the corner looks like a likely place to find a silver teapot in, eh? Well, then—Whoosh!” he said suddenly, and began pawing at his face with both stands. “Spiders! Ugh, how I hate the nasty things!” For Mr. Webb had dropped from a rafter on to Uncle Snedeker’s nose, and had run down across his face and then jumped to the floor.

Uncle Snedeker brushed himself off, and then he picked up the candle and looked around, but didn’t see anything. If he had looked up, he would have seen Mrs. Webb, but he didn’t. He was just starting for the big chest when Mrs. Webb jumped.

Uncle Snedeker was pretty bald, and Mrs. Webb landed on the top of his head and skidded halfway down his forehead before her feet took hold properly. She ran down his face and jumped just as Mr. Webb had done. Then she and her husband climbed back on to the rafter, all ready for another jump, if it should be necessary.

But it wasn’t necessary. For Uncle Snedeker was still saying “Whoosh!” and “Phow!” and all the other things people say when bugs drop on them, when Jinx gave a low ghostly moan. Uncle Snedeker dropped his candle and bolted down the stairs and slammed the door at the foot of them behind him.

Well, they had saved the teapot for the time being, but Jinx was certainly worse off than he had been before, for he was shut in the attic with no way to get out. Of course he could sit down and howl, and if he howled long enough, somebody would come and let him out. But he had an idea it would probably be Aunt Effie who would come, and Aunt Effie was entirely too handy with a broom.

He talked it over with the Webbs, but they couldn’t think of anything. “I tell you what I’ll do though, Jinx,” said Mr. Webb. “I’ll go on down to the pigpen and tell Freddy. Maybe he can organize a rescue party.”

But Jinx said no. There was a heavy dew that night, and although it was nothing that would have bothered you or me, a spider would be certain to step into a dozen puddles that were over his ankles. And Mr. Webb was subject to colds. He had had one cold after another all that spring.

Mrs. Webb was much relieved. “I’d rather Webb didn’t go, and that’s the truth,” she said. “He feels so bad when he has a cold, and then he sneezes all the time, and the flies hear him and get away. You know yourself, Jinx, it’s no use going out hunting if you’re sneezing every two seconds. It got so the flies just laughed at him. They sat in rows on the wall and waited for him to sneeze and they laughed their heads off. They even invited their friends to come hear the sneezing spider. You can’t imagine how trying it was.”

“Jinx doesn’t want to hear about our troubles, Mother,” said Mr. Webb. “Besides, that’s all over now.”

“I just wanted him to understand why I thought you oughtn’t to go,” said Mrs. Webb. “But goodness, I’ll go down and tell Freddy myself. A breath of air’ll do me good.”

But Jinx wouldn’t hear of it. “No indeed, ma’am,” he said. “I certainly won’t let a lady do a thing I can’t do myself. No, no; I’ll just curl up here on this old mattress and Webb can see Freddy in the morning.” And so they left it at that.