Chapter 3

Jinx had forgotten all about Little Weedly, whom he had left curled up on an old blanket in the box stall of the barn. But Little Weedly hadn’t forgotten Jinx. He lay there staring into the darkness and wondering why his handsome new uncle didn’t come back. For Jinx had said he’d only be a few minutes. “Oh dear, oh dear!” said Little Weedly to himself. “Why doesn’t he come?” And like all scary people, he began trying to scare himself worse, by thinking of all the terrible things that could have happened to Jinx, until he was in a regular panic.

In the stall next door he could hear Hank, the old white horse, breathing in long slow breaths, and occasionally muttering in his sleep. You can’t imagine anything much more peaceful to listen to. But if you want to scare yourself there are always, in any old building, creaks and snaps and rustlings that you can imagine are bears or burglars or bugaboos of unprecedented ferocity, just crawling up on you and waiting to pounce. And so by the time there did come a sound that he really couldn’t explain, Weedly was almost ready to fly into a fit.

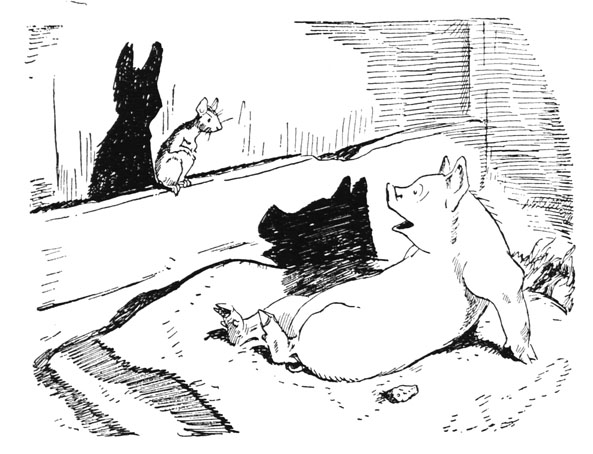

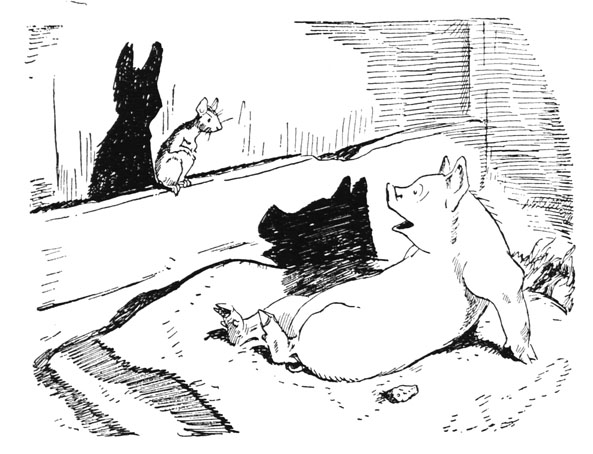

It wasn’t a very large sound. In fact, if you or I had been lying awake and had heard it, we would merely have said: “H’m, mouse somewhere,” and would have turned over and tried to go to sleep. And we would have been right, too, for it was a mouse named Quik, who was sitting on the edge of the manger just over Weedly’s head, eating a peanut.

Quik and his three brothers, Eek and Eeny and Cousin Augustus, had gone to bed at their regular time, up in the hay mow. Usually they lived in the house, but while the Beans were away there weren’t any crumbs under the dining room table, or any little saucers of things that Mrs. Bean left out for them, so they had moved down into the barn. The other three mice had gone right to sleep, but Quik had been wakeful, probably because he had eaten a coffee bean at dinner, and at last he had got up. He crawled out of the hay and walked up the wall to a hole under the eaves, and out on to the roof. But an owl hooted and he went back in again. All of the owls in the neighborhood were friends of his, but it is hard to recognize friends in the dark, and if there was a mistake it would be too late to explain who he was after he was eaten. So he went back in and foraged around in the part of the barn where the boys used to play when they were home. For where there are boys, there are usually crumbs. And sure enough, he found an old peanut.

Quik took the peanut into the box stall and climbed up on the manger and started to eat it. It was so dark he didn’t see Weedly at all. The peanut was pretty stale, but Quik didn’t get peanuts very often and I’m afraid he smacked his lips a good deal as he munched it, although mice, as a general rule, have very good manners. It was this smacking that Weedly heard. He began to tremble, and that made a rustling noise. Quik looked down and saw something white on the floor that moved a little bit, and that startled him so that he dropped his peanut, which hit Little Weedly on the nose. And then Little Weedly lost all control of himself, and began to squeal “Help! Mamma! Help!” at the top of his lungs, and he ran, still squealing, out into the barnyard.

For his size, a pig can squeal louder than almost any other animal. Little Weedly was small but in five seconds every animal on the Bean farm was tumbling out of bed, shouting: “Hey! What’s wrong? What’s the matter?” Quik, who had, of course, been nearest the first squeal, fainted dead away and didn’t come to until all the excitement was over. Hank woke up with a snort, and came clumping out, and Robert and Georgie, the two dogs, rushed out, and the three cows, Mrs. Wiggins and Mrs. Wurzburger and Mrs. Wogus, pushed aside the little lace curtains at their windows in the cowbarn and stuck their broad noses out. Freddy came out of the pigpen, and the ducks, Alice and Emma, came waddling up from the pond as fast as their short legs could carry them, and the chickens, clucking and cackling, piled out of the henhouse, Henrietta in the lead, and Charles, the rooster, as usual, talking very loud, but bringing up the rear.

When Little Weedly came out of the barn door, he headed straight for home. He dodged through the animals that were gathering in the barnyard, and galloped up across the brook and into the woods, yelling all the time. He was afraid of the dark night, and of the woods, but he was more afraid of that box stall where he had had the terrible experience of having a peanut drop on his nose out of nowhere. And if he had got home, this story wouldn’t have had much more to say about him. He would have gone down in history just as a terribly bashful pig, and that would be the end of him.

But up in the woods the squealing had been heard, too. Birds stirred on the branches, and rabbits and chipmunks and squirrels came to their doorways and sniffed and pricked up their ears. And Peter, the bear, who had been curled up in the raspberry patch, where he had been sleeping lately so that he could keep an eye on the blue jays who came early in the morning to steal his berries, got up and came sleepily out to see what was going on. And he came out right in the middle of the path up which Little Weedly was galloping.

Bears are good-natured animals. They aren’t any more ferocious than mice; they’re just bigger. Down the path Peter could just make out that something was coming, and he stood up on his hind legs to see better. Weedly came tearing along toward him, screeching like a fire engine, but just before he got to the bear he stumbled over a projecting root and fell flat.

“Hello there,” said Peter. “You must be the little pig that says ‘Wee, wee’ all the way home. What’s all the trouble?”

Weedly looked up and saw towering over him, a great shaggy animal, such as he had never seen before. Peter held out a big paw to help him up, but Weedly thought the creature was trying to catch him. He jumped up and tore back down the path the way he had come, squealing just as loud as he had before. Only now he was calling on his Uncle Jinx for help, instead of his mother.

… he tore back down the path.

“Well, my goodness!” said Peter, and went back to the raspberry patch.

In the Bean barnyard, the animals had gathered around Freddy, who was telling them about Little Weedly. “Jinx said he’d look after him,” said the pig, “but evidently Jinx has gone off hunting somewhere, and he got scared. Do you know what scared him, Hank?”

“Didn’t know anything about it till he began squealing,” said the horse. “My land, he scared me out of a year’s growth. He ain’t coming back, is he, Freddy?”

“He didn’t sound as if he intended to,” said the pig. “No, he’s gone back home, and I don’t believe—”

“Yeah, he’s comin’ back,” said the horse gloomily. “Listen.”

The squeals which had got fainter and fainter and died away in the distance had begun again, and were getting louder and louder. “It’s like these moving pictures of races,” said Georgie, “and then you see them run over again backward.” Louder and louder. “Help! Uncle Jinx! Help!” yelled Weedly, and then he was in the barnyard, and he scattered the animals as he dashed through them and disappeared again into the barn.

“There goes my night’s sleep,” grumbled Hank.

“Where on earth is Jinx?” said Mrs. Wiggins. “He’s the one to be looking after the poor little creature.”

But Jinx had heard the squeals. He had been just dropping off to sleep when they began. “My goodness,” he said, jumping up, “it’s Little Weedly! I forgot all about him! Oh, I’ve got to get out of here!”

Jinx didn’t waste any time. The only way to get out was through the door, and as he couldn’t open it himself, either Aunt Effie or Uncle Snedeker would have to open it for him. He climbed up on a big pile of boxes and began pushing them one after the other on to the floor.

After the bang that each box made in falling, he listened a minute, and at last he heard what he had been waiting for—voices in the hall. He went down close to the door.

“Eh, eh, I’ll open it, Effie, I’ll open it,” he heard Uncle Snedeker say. “But ain’t it kind of foolhardy, Effie? Indian warwhoops, that’s what those yells were if I ever heard ’em. And then the noises in the attic—that’s the way the Indians come; cut a hole in the roof and then creep in, all silent and stealthy, and first thing you know—zip! And you’re scalped.”

“Nonsense!” said Aunt Effie sharply. “There hasn’t been an Indian around here for two hundred years. And if there was, what good would your scalp do ’em, I’d like to know?”

“Eh, that’s just it,” said Uncle Snedeker. “‘Tain’t myself I’m thinking about. I’m balder’n an old eagle. But your nice long, thick hair—eh, I’d hate to have you lose it, Effie. All the trouble you’ve had combin’ and curlin’ it—”

“Snedeker,” interrupted Aunt Effie, “open that door!”

There was a pause, and then as the knob turned, Jinx got ready. And when the door slowly opened he dashed through.

Even then he was hardly quick enough. Uncle Snedeker gave a yelp and staggered back, but Aunt Effie was made of sterner stuff. “There’s your Indians!” she exclaimed, and swung with her broom. It missed Jinx by the width of his tail, and then he was dashing down the stairs, with Aunt Effie in pursuit.

It was lucky for the cat that the Snedekers had thrown up the front parlor window to see what all the noise was about. He made one bound from the foot of the stairs to the parlor door, another to the windowsill, and the third landed him on the ground and in safety, with Aunt Effie shaking her broomstick at him from the window. At another time Jinx would have sat down in full view of Aunt Effie and calmly washed his face, pretending all the time that he didn’t see her, that he never had seen her before, and that he hadn’t the slightest interest in anything concerned with her. And he probably would have succeeded in making her good and mad. But now there were other things to attend to. So he went over to the barn.

Little Weedly was cowering in the farthest corner of the box stall. He was about worn out—not so much because he had been running, as because he had been yelling. For yelling is about the hardest exercise there is, and if a lot of people who weigh too much would just yell ten minutes a day, instead of playing golf or tennis or swinging Indian clubs, they would reduce very quickly. Only, of course, the neighbors probably wouldn’t like it much.

“Well, well, Weedly,” said Jinx, “what’s wrong here? Who’s been playing tricks on you?”

“Oh, Uncle Jinx,” panted Little Weedly, “I’m so glad you’re here. It was awful!”

“What was awful?” said Jinx. But Weedly couldn’t tell him. It was awful, and it had scared him; that was all he knew.

“Well, you’re all right now,” said Jinx. “You go to sleep, and I’ll be back in a minute. I’m going to get to the bottom of this.”

So he went out to get to the bottom of it. The animals were still standing around the barn door. “You fellows ought to be ashamed of yourselves,” he said angrily, “playing tricks on a poor little helpless pig.”

“Nobody played tricks on him, Jinx,” said Robert. “As far as we can make out, he just scared himself, because you’d gone off and left him alone. After all, you adopted him; why didn’t you stay with him?”

“Because I had important business to see to, for Mr. Bean,” said Jinx.

Henrietta cackled drily. “Yes, we know the kind of important business. Down on the flats chasing frogs, probably. You’ve got about as much sense of responsibility as—well, as Charles here. I can’t put it any stronger than that.”

“Oh, come, Henrietta,” said Charles, “just because you asked me to sit on those eggs this afternoon, and I forgot and went down to swim—”

“Now, now,” put in Mrs. Wiggins good-naturedly, “one thing at a time. Are we discussing Charles’ shortcomings as a husband, or Jinx’s shortcomings as a guardian? What was this business, Jinx? You’ve got something important to tell us, I know.”

“Yes, if you’ll let me tell it,” said Jinx grumpily. “I couldn’t be with Weedly because I was locked in the attic.” And he told them his story.

The animals were a good deal worried by the news. They had heard from Freddy about the result of the sheriff’s visit, and so they knew that the Snedekers really were Mr. Bean’s relatives. It was probably going to be unpleasant enough trying to get along with them until the Beans got home, but nobody had supposed that they were really up to any mischief.

“We mustn’t let them get that teapot if we can help it,” said Mrs. Wiggins. “But I don’t see how we can help it. Even if one of us could get in and get it, he certainly couldn’t get out with it. Of course, I’m not very good at thinking up things. Maybe one of you animals has got an idea.”

“I’m afraid I haven’t,” said Freddy.

“Land sakes,” said Hank, “don’t look at me!

“Peter could get in,” said Georgie. “He’s terrible strong. He could just push the door in and walk upstairs and get the teapot, and then walk out with it. And if she came after him with the broom, he’d just laugh.”

“Yes,” said Jinx, “and what if, instead of the broom, she picked up Mr. Bean’s shotgun? We don’t want to spend the rest of the summer picking birdshot out of poor old Peter. No, we can’t prevent them getting the teapot. But what we’ve got to prevent them from doing is taking it back to Ohio. We’ve got to keep them here either until we can get it away from them and hide it, or until the Beans come home.”

“And I know how we can do that,” said Freddy suddenly. “Jinx told you what Aunt Effie said; that she thought it was terrible to leave a farm with nobody but the animals to look after it, and that she was going to see that it was properly run. You see, she’s one of those people that can’t stand it to see things being misused, and not taken care of. Even if they aren’t her things. So all we’ve got to do is make her think everything on the farm is going to pieces, and then she’ll stay here until she gets it all in good shape.”

“Gosh, that’s an idea, Freddy,” said Jinx.

“Maybe it is,” said Mrs. Wiggins. “Maybe it is. I’m not much good at ideas myself, and that’s a fact. You mean, Freddy, that if there’s a hole in the barn roof, she’ll stay until she gets it mended?”

“Exactly,” said Jinx, “and I know just where we can make a hole in the barn roof. It’ll keep her busy here for one day, anyway. There’s some loose shingles I noticed the other night when I was up there singing.”

“Yeah,” said Hank, “and I guess maybe it was your singing that loosened them. If I had that gun you were talking about, there’d have been a hole in that song of yours that it would take more than Aunt Effie to patch up.”

“Why, Hank,” said Jinx with a grin, “don’t you like music?”

“Sure,” said the horse. “But I thought we were talking about your singing.”

Jinx couldn’t think of anything to say to that so he just said, “Pooh!” And then after a minute he said: “Well, as I was saying, I can go up and tear some of those shingles out—”

“You’re not going to leave that little pig alone any longer,” said Mrs. Wiggins firmly. “You brought him here, and you’ve got to look after him. Though what you’re going to do with him, I’m sure I don’t know.”

“Pooh,” said Jinx, “you leave it to me. He’ll turn out all right; you wait and see. He’s smart, that young one—smart as a whip. He’ll get over being so bashful and scared in a little while. We were all that way once ourselves. Why, when I was a kitten—”

“When you were a kitten,” said Mrs. Wiggins, “you were the worst nuisance on four legs. You were about as bashful as a pack of firecrackers, and just about as comfortable to have around.”

“Oh, that was later,” said the cat. “I really was scared of everything though. And do you know what cured me? I was down playing in the brush-lot with my mother one day. My mother was pretending she was a mouse, and I was jumping out and pretending to scare her. Well, she hid, and I was hunting for her when I saw something come poking through the bushes. I thought it was mother, and I made a jump and landed with all four feet right on your nose. You’d heard something moving in the bushes and had poked your nose in to find out what it was. Ho, ho!” Jinx laughed, “talk about Weedly making a noise! They could hear you over at Witherspoons’.”

Mrs. Wiggins smiled, and if you have never seen a cow smile, you don’t know how large and comfortable and pleasant a smile can be. “I guess I did make quite a commotion,” she said.

“I’ll say you did,” said Jinx. “And I wasn’t ever scared of things after that. When I knew that an animal fifty times as big as I was, was afraid of me—” He stopped suddenly. “Golly!” he said. “That’s how we can cure Weedly. If we all pretend to be afraid of him—”

“Pretend to be afraid of a pig?” exclaimed Charles, ruffling up his feathers indignantly.

“Sure. When you see him, squawk and run away and hide. Give him the big build-up.”

“Well, I certainly shall do nothing of the kind,” said the rooster. “Why, it’s—it’s undignified.”

“Ha!” said Henrietta. “That’s a good one—from you.”

“Let me handle this, Henrietta,” said Jinx. “Come on, Charles, be a sport. Just to please me. The others will all do it; won’t you, animals?”

“’ Twouldn’t be any trouble for me,” said Hank. “I’m scared of the critter now.” And Freddy and Robert and the other animals said, well yes, they’d try it.

But Mrs. Wiggins shook her head. “I don’t know, Jinx,” she said. “I’m willing to do anything within reason. But I can’t go cavorting off over the hills in hysterics every time I see him. How would it be if I just look startled?”

“How do you look when you look startled?” the cat asked, and Mrs. Wiggins thought a minute, and then she opened her eyes wide and dropped her jaw and waggled her ears. “Guess that’s about it,” she said.

“Good gracious!” said Jinx. “You’d scare him to death!”

“H’m,” said Mrs. Wiggins. “Well, how’s this?” And she suddenly sat down weakly, and closed her eyes, and put one front hoof to her heart and said: “Oh! Oh, dear! Oh, dear me!”

“Splendid!” said Freddy. “Mrs. Wiggins, you’re a born actor. My goodness, that gives me an idea. Good night, you fellows.” And he trotted off toward the pigpen.

“That’s what it is to be a poet,” said the cat disgustedly. “Right in the middle of something, you get an idea and have to go write it down, and leave the other fellow to do the work. Well, anyway, I guess it’s all settled that you’ll help me out with Weedly. I know it’ll be a nuisance, but he’s a swell little pig, really. And I know you’ll help him a lot. Besides, you’ll be doing something for me. And I don’t ask favors of you very often.”

“No, that’s true, Jinx,” said Henrietta. “You can count on the chickens—and that includes Charles, of course.” And she moved over beside her husband and smoothed down a feather on the side of his head with her beak.

Charles started, and eyed her suspiciously. Her beak was very close to his ear, and although a rooster’s ear isn’t large, it is very sensitive. “Well,” he said, “I—er, that is, certainly, Jinx. I am only too pleased to take any steps which would tend to ameliorate the conditions surrounding the education of your adopted nephew, and I will say here and now—”

“Don’t make a speech,” said Henrietta sharply.

“—that I—er, that is, you can count on me,” concluded Charles.

“Fine,” said Jinx. “And now that’s settled, I’ll go fix that roof. Don’t worry—I’ll take Weedly along so he won’t cause any more trouble.”