Chapter 11

Little Weedly trotted along up the bank of the brook towards the woods. “An old bird!” he said to himself. “As if I couldn’t scare an old bird!” And he giggled.

Pretty soon he came to the duck pond. He thought he’d sneak up quietly behind a bush and if Alice and Emma were there, he could scare them again. And sure enough, there they were. But they were acting very queer. They were sitting on the bank, looking very sad, and first Alice would give a deep sigh and say: “Oh, deary, deary me!” and then Emma would give a deeper sigh and say: “Alas! Alackaday!” And then they would look at each other and sob.

Weedly watched them for a few minutes. Then he giggled. “My goodness!” he said. “When I scare ’em they certainly stay scared. I guess maybe I’d better not do it again.” Then he began to feel sorry for them, because they seemed so terribly unhappy, so he crept backward out of the bush and then came walking along again towards the pond until they caught sight of him.

“Is there something the matter?” he said. “Are you in trouble?”

The ducks stopped sighing and looked up at him.

“It’s that little pig that Jinx adopted,” said Alice to her sister. “No,” she said to Weedly, “we’re just practicing being sad for the play Freddy is going to give. We’re to have parts in it, you know. We’re ladies-in-waiting to the queen, and we have a secret sorrow.”

“My goodness, there isn’t anything very secret about it,” said Weedly. “I should think if it was a secret sorrow you’d try to hide it. I should think you’d have to act very happy.”

The ducks looked at each other. “Dear me,” said Emma, “we didn’t think of that, sister. I suppose we ought to act very gay. Like this.” She gave a little quacking laugh, and then quickly turned her head aside as if to wipe away a tear.

“That’s it, sister,” said Alice. “That’s it. A laugh that hides your breaking heart, and then to show that your heart really is breaking, under all your gaiety, you stop laughing and cry a little.”

“Oh, yes, I think that is much more artistic,” said Emma. Then suddenly she looked sharply at Weedly and said: “Why, you’re the little wretch that jumped out and said ‘Boo!’ at us! I remember now.”

“Well, yes,” said Weedly. “I did. I scared you good, didn’t I?” He tried to laugh, but the ducks were both looking at him now so ferociously that he thought he’d better not. “I—well I hope you aren’t mad,” he said, beginning to back away. “It was just in fun.”

“In fun, was it?” said Emma. “Well, it wasn’t fun for us, I can tell you. If our Uncle Wesley was here you wouldn’t dare do such a thing.”

“Just in fun indeed!” exclaimed Alice. “You’d better keep away from this pond in the future if you don’t want to get into trouble.” And both ducks, with wings spread and bills outstretched, came waddling towards him.

Weedly didn’t wait any longer. He turned and ran.

He didn’t run very far. After a minute he looked back, and the ducks were sitting on the bank again, practicing being sad, so he slowed down. He walked up along the brook, and then he took the path which went up into the woods. It was bright and sunny out in the meadow by the brook, and he could hear birds calling and dogs barking and a mowing machine whirring and the far-off whistle of a train, so that he knew that all around him the world was going on, full of happy, busy people. But in the woods it was dim and still. He walked along in a green twilight, and the sounds of the outside world were shut off from him by the tall silent tree trunks that, wherever he looked, seemed to close him in. There were sounds, but they were different—mysterious rustlings, and now and then the mournful whistle of a pewee, or the queer ringing notes of a wood thrush.

Lots of people like the mysteriousness of the woods, and so of course do lots of animals, even those that don’t live there. Jinx loved the woods, and he used often to wander around in them by himself, and sometimes he would spend a whole day hiding in them, not to catch anything specially, but just for the fun of hiding. But Little Weedly was a pig, and pigs don’t like to be alone much. So as he went along, he walked slower and slower. He didn’t exactly jump when he heard little noises because he wasn’t exactly scared, but he wasn’t exactly comfortable about things either. It was fun pouncing out on people, but suppose something pounced out on him? He wondered what an owl was like. A big, fierce-looking bird, probably. Well, he’d said he was going to scare Old Whibley, and he was going to do it. But maybe he’d better not scare him too much.

So as he got nearer the big maple where Freddy had told him Old Whibley lived, he left the path and began creeping along through the underbrush. He crept from tree to tree like an Indian, and pretty soon he saw the maple. It was big and tall, and maybe fifty feet up, where it divided into great thick limbs, there was a hole. Weedly was peeking out from behind another trunk at it when a voice said sleepily: “Ho hum.”

Weedly pulled his head back so quick that he bumped his nose on the tree trunk. When he had rubbed it till it stopped hurting he stuck it out again cautiously. A big bird was sitting on a branch a little above him. The bird had his eyes closed and seemed to be asleep, though he wasn’t sleeping, like most birds, with his head underneath his wing. Weedly ducked back behind the tree again. “My goodness,” he said to himself, “I wonder if that’s Old Whibley. He doesn’t look very ferocious. I wouldn’t be afraid to scare him.” And he was just getting ready to jump out and yell “Boo!” when the voice said: “Stop acting so silly and come out from behind that tree. I won’t hurt you.”

Weedly hesitated a minute and then he came out. “I—I thought you were asleep,” he said. “I’m not afraid of you,” he added quickly.

The bird opened one enormous yellow eye. “I’m not afraid of you either. That makes us even,” he said. “Well, what do you want? Advice?”

“I—well, no, I guess not,” said Weedly. “I was just wondering—are you Old Whibley?”

“That depends,” said the bird, closing his eye again. “Who sent you?”

“Nobody, I just came. By myself.”

“And you want to see Old Whibley?”

“Yes,” said Weedly. “That is—no, not exactly.”

The bird opened both big round eyes and stared at him. “Yes—no, yes—no. What kind of an answer is that? Either you do or you don’t. Can’t waste time with people that don’t know their own minds. Old Whibley isn’t home.” He closed his eyes.

“Oh,” said Weedly. He looked at the bird a minute and then he said: “Well, if you aren’t Old Whibley, maybe you can tell me where I can find him?”

“You here again?” said the bird crossly, opening his left eye. “Well, tell me what you want with him. Then maybe I’ll help you. Maybe I won’t, too.”

“I guess you don’t know who I am,” said Weedly, who was beginning to get cross. Silly old sleepyhead! Why couldn’t he give a plain answer? “I’m Little Weedly, and Uncle Jinx—”

“I know,” the bird interrupted. “He adopted you. Don’t give me your family history.”

“My family’s all right,” protested Weedly.

“I daresay,” said the bird. “I don’t want to hear about it, that’s all.”

“Oh, dear,” said Weedly, “you get me all mixed up. It isn’t anything important. I’ve just been having fun today scaring the animals on the farm, and Cousin Frederick said I couldn’t scare Old Whibley, so I thought—”

“You thought you’d scare him,” said the bird. “Not a bad idea. You jump out and say ‘Boo!’ I suppose. Some people enjoy that kind of thing. But how are you going to work it? Old Whibley in the treetops, you on the ground. He wouldn’t even hear you.”

“Oh,” said Weedly. “I didn’t think of that.”

“You wouldn’t,” said the other. “Still, if you could get up in his hole there, in that tree—eh? Then when he comes home, stick your nose out and say ‘Boo!’”

“Oh, if I only could!” said Weedly. “But I can’t climb a tree!”

“We can fix that,” and the bird gave a hooting cry, and immediately another bird of the same kind, only a little smaller, came floating down from somewhere high up in the treetops and lit on the branch beside him. “My niece, Vera,” he said to Weedly. “Vera, this is Weedly, who wants to scare Old Whibley. Wants us to take him up into Old Whibley’s nest so he can jump out and say ‘Boo!’ at him when he comes home. Very funny idea.”

“Very funny indeed,” said Vera. But neither of the birds laughed.

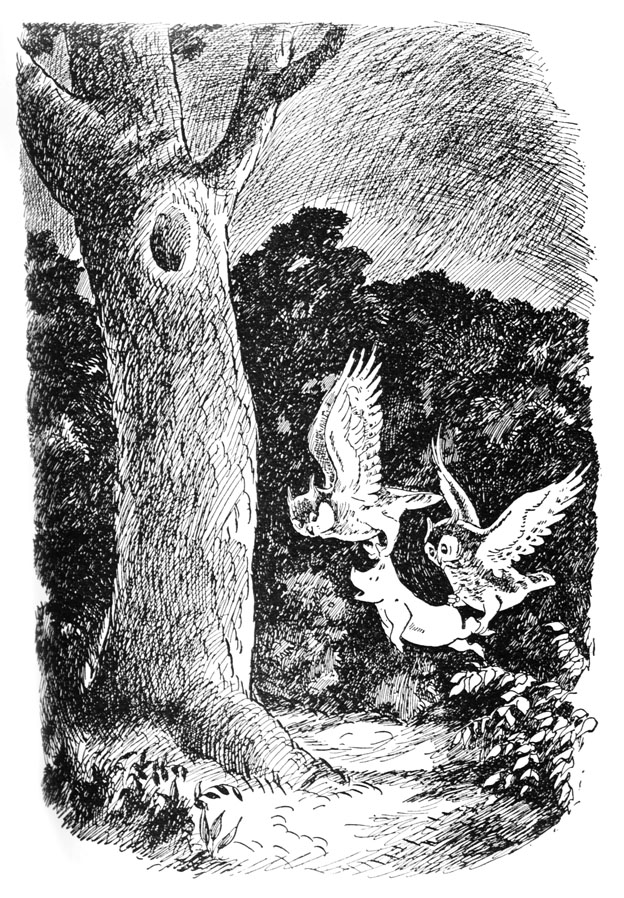

“I guess,” said Weedly doubtfully, “that I’d rather wait till some other day. I guess—” But he didn’t finish, for the two birds suddenly swooped upon him, seized him with their strong beaks and claws, and with powerful flapping wings bore him up to the hole high in the trunk of the giant maple.

… the birds suddenly swooped upon him.

“There you are,” said the first bird. “In you go. Hang on, there.” And they tumbled him into the deep cavity, which was filled with sticks and leaves.

“Oh, dear!” said Weedly. “Oh, dear!” For his left ear and his tail had been badly pinched in the strong beaks, and the claws had dug into his plump little sides like big fishhooks. “How will I ever get down?” he moaned.

The two birds sat outside and looked at him. “Don’t you worry,” said Vera. “We’ll carry you down after you’ve given Old Whibley a good scare.” And she laughed for the first time.

“But when do you expect him?” said Weedly anxiously.

“Can’t tell for sure,” said the first bird. “But he ought to be back in a week or two.” And both birds opened their eyes very wide at him, and then burst into hoots of laughter and flew off.

“A week or two!” said Weedly. And then he thought of that hooting laughter. “I’ve heard that sound before,” he said to himself. “And mother told me it was owls. Then if they’re owls—why,” he exclaimed, “I bet that was Old Whibley himself! Oh, dear!”

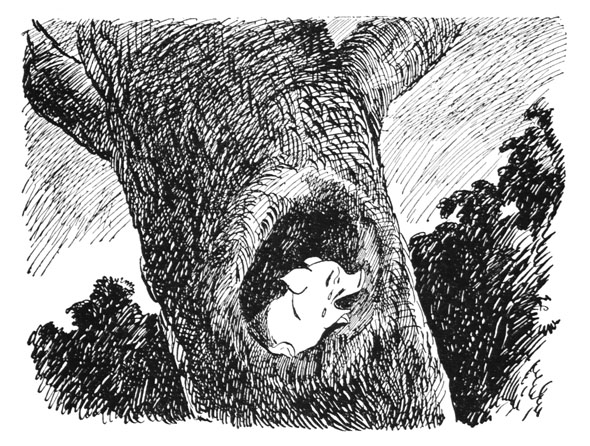

It wasn’t very smart of Little Weedly not to have thought of that before. But of course he had never seen an owl. And then, although he thought it was funny to play tricks on other animals, it had never occurred to him that they might think it funny to play tricks on him. He wasn’t very happy. Here he was in a hole in a tree fifty feet above the ground, and he didn’t believe that those owls had any intention of coming back and taking him down. Not for a long time, anyway. He stuck his head out and yelled as loud as he could for his Uncle Jinx. But in the thick woods his voice didn’t carry very far, and nobody heard him. And so, after he had yelled himself hoarse he did a very sensible thing. He curled up and went to sleep.

When he woke up it was beginning to get dark. At first he couldn’t remember where he was. He got up sleepily and started to go out of the door, but just as he was going to step over the edge he looked down and saw the ground way below him, and he gave a yelp and jumped back. He stayed quiet after that, and it got darker and darker. He was hungry now, too. Back at the farm, he knew, the animals were all sitting down to their supper, talking and laughing and never giving a thought to the terrible danger he was in. He yelled for a while, but nobody came, so he went to sleep again.

The next time he woke up it was really dark. Out in the open fields, even when it is cloudy, it seldom gets as dark as it does in the deep woods. Weedly couldn’t even see the door. At least he couldn’t at first, but after a minute he knew where it was, because through it he saw a queer flickering light coming towards him through the trees. He didn’t know what it was, but then at a little distance he saw another light, and another, and after a minute he heard voices.

“Help!” he yelled. “Uncle Jinx! Here I am. In Old Whibley’s nest.”

The lights came together and approached the tree, and he saw that it was Jinx and Freddy, and the two dogs, Robert and Georgie. And on each head was a little flickering green light.

“What on earth are you doing up there?” said Jinx. “We missed you at supper and we’ve been hunting all over the farm for you.”

The light on Jinx’s head seemed to fly apart into sparks, which floated up towards the owl’s nest, and then came together again on the bark just over the door. Weedly saw now that they were fireflies.

“I want to get down,” he said.

“Yeah,” said Jinx drily, “I suppose you do. Well, you got up there somehow, so I suppose you can get down.”

“But I can’t,” said Little Weedly. “That old owl carried me up here.” And he told them how the trick he was going to play on Old Whibley had been turned against himself. “He’s a mean old thing,” he said.

“That’s where you’re wrong,” said Freddy. “There isn’t a mean feather on Old Whibley’s body. He did just right, if you ask me. You’ve been getting pretty fresh lately, Weedly.”

“He’s just played a joke on you,” said Robert. “He wouldn’t let you stay up there much longer. He’ll be back before long to take you down. He’s a good fellow.”

There was a sudden loud hoot above them in the tree and Old Whibley’s voice said: “Thanks for the compliments, gentlemen. You didn’t know I was up here, so I take it they’re sincere. Well, want me to bring him down?”

“I don’t want him to bring me down,” said Weedly. “He—he clawed me, carrying me up.”

“Clawed, nothing,” said Old Whibley contemptuously. “Want to know what it’s like to be really clawed? I’ll come in there and show you.”

“You let me alone,” said Weedly. “Uncle Jinx, you make him leave me alone.”

“Suit yourself,” said the owl. “Can’t wait around here all night. Evening, gentlemen.”

“He’s gone,” said Georgie. “He’ll be back, all right. But look, Jinx, we can get Weedly down if we have some rope.”

“I’d like to get him down,” said Jinx. “Whibley’s a good scout, but he don’t know what a time I’ve had getting Weedly not to be so scared. If he’s left up there all night, he may be just as scary as he was when he first came here, and then we’ll have to train him all over again.”

“If he was my nephew,” began Freddy, but Jinx interrupted. “Well, he isn’t,” he said crossly.

“All right, all right,” said the pig. “I have something to be thankful for, then. Well, come on, Georgie; you and I’ll go get the rope.” And they trotted off, the clusters of fireflies on their heads showing them the way like the little lanterns miners wear in their hats.

In half an hour they were back with the coil of rope. “We brought a ball of cord too,” said Freddy, “because the rope will be too heavy to carry up all that distance.”

“Hey, boys,” Jinx shouted to the fireflies over Old Whibley’s door, “go on up and find me the first branch directly over the door opening.”

The fireflies broke apart and clustered again on a branch about three feet higher up.

“Fine!” said Jinx. “Hold it!” And he took one end of the cord in his mouth and began to climb. He went up past Weedly to the branch, dropped the end of the cord over it, and then sat on the branch and pulled the cord up and over it until the end reached the ground, where Freddy, who was awfully good at knots, tied it to the end of the rope. Then he and the dogs got hold of the other end of the cord and pulled on it until the rope was up over the branch.

Jinx took the rope end in his mouth and slithered down the trunk and into the nest, where he tied it around Weedly’s waist.

“All ready, fellows?” he shouted. “Get a good grip on the rope now while I swing him out.”

“We’ve got it,” said Robert, as he and Georgie and Freddy seized the rope in their teeth and braced themselves.

For a wonder, Weedly did not protest at being pushed out to dangle over fifty feet of thin air. Perhaps it was because he had so much confidence in his adopted uncle. He only gave one faint squeal as his feet slithered over the edge of the doorway. He kicked a little when Jinx shouted, “Lower away!” and he began descending in jerks. Some of the jerks were pretty jerky, too, particularly the one when Freddy fell over a log. But they brought him to ground safely. And then from up above them came Old Whibley’s voice again.

“Nicely done, gentlemen.”

“My gosh,” said Jinx, “were you there all the time? You might have helped us.”

“I might,” said the owl.

“Letting us do all that work.”

“I’m like you that way,” said Old Whibley. “Never do work if I can get someone else to do it for me.”

“Aw, rats!” said Jinx disgustedly. “I ought to know better than to argue with you.” And he turned and cuffed Little Weedly severely. “Now,” he said, “get along home. I’m not very pleased with this night’s performance. You’re not a very good sport, I guess. You can dish it out all right, but you can’t take it.”

“Don’t be too hard on him, cat,” said Old Whibley, and they all looked up in surprise. “It’s easy enough—telling somebody else to be a good sport. Remember the time that rat down in Macy’s barn—”

“All right, all right,” Jinx interrupted hastily. “We haven’t time for all this talk. It’s Weedly’s bedtime.”

“Put him to bed then, and don’t lecture,” said the owl. “He hasn’t done so badly, and if he’s still mad at me, I guess I can bear it.”

“I’m not mad at you, Mr.—Mr. Whibley,” said Weedly.

“Good,” said the owl. “Just remember, there’s two ends to a joke. Depends on which end you get hold of whether it’s fun or not. Now get along and take those lightning bugs out of here. They hurt my eyes.”