Nowa Fantastyka Nov 2016

You may know that I was a biologist long before I was an author. You may not know how far back those roots extend, though: years before I ever stepped onto a university campus. Way back into childhood, in fact.

I was really bad at biology back then. I was downright horrific. Now I am old, and remorseful, and afflicted with some weird disease that nobody seems able to identify; so I figure I should make my peace. Consider this a deathbed confession, delivered early to avoid the rush.

My intentions were always honorable. I love other creatures almost as much as I hate people; the running joke of my life is that I’m a bad biologist because I have too much compassion, can’t bring myself to experiment on fellow beings with the ruthless dispassion that Science demands.

But I don’t just love life; I want to know how it works, I always have. I decided to be a biologist at age seven; by fourteen I was building metabolic chambers out of mason jars.

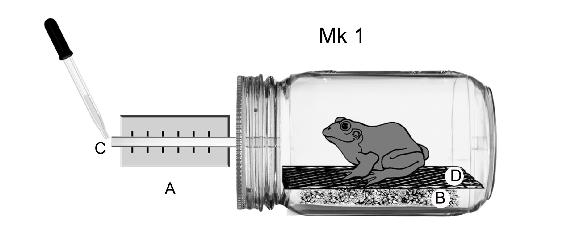

That’s actually easier than it sounds. Stick a straw (A) through the lid of a mason jar. Put some CO2 absorbant (B) inside (I used Drano). Insert an animal, tighten the lid, and—this is the cool bit—seal the end of the straw with a soap bubble. Animal inhales O2, exhales CO2; Drano absorbs CO2, reducing the volume of gas in the jar and pulling the bubble along the straw. If you know the straw’s volume, you can measure the O2 consumption of anything inside by timing the rate at which the bubble moves.

Cool, huh?1

One thing, though: Drano is corrosive, so you want to keep it away from your animal. I kept mine safely under a plastic grille (D) that served as the floor of the chamber. It worked great. The only potential risk was when you took the animal out afterward, which you did by sliding the grille from the jar like a tiny drawer.

Especially if the animal was a jumper. A toad, for instance.

In my defense, the mouth of that jar was a pretty small bullseye given all the directions in which he could have jumped. Any random leap off the grille should have missed it completely. But maybe this particular toad liked that jar. Maybe he felt safe there. For whatever reason, he jumped unerringly off the grille, back into the jar, and landed smack-dab in the Drano.

I grabbed him instantly, of course. Ran to the sink, thrust him under the running water to rise him clean and his back half just—

—washed away . . .

I kept the front half—still blinking, a little confused—in a shallow bowl next to my bed so I could check on it during the night. I was a wuss as well as a bad biologist, you see; I didn’t have the heart to smash the little guy with a hammer, put him out of his misery. (I got better at that over the years, at least. You don’t spend a lifetime with cats without learning to put small things out of their misery. Remind me to tell you sometime about the bouncy, impact-resistant, almost indestructible elasticity of various kinds of eyeballs. They ought to build cars out of the stuff; I’m sure it would save lives) I guess on some level I held out hope that he might survive.

He didn’t. He was dead by midnight, and I had killed him.

Maybe I should have laid off the whole experimental-biology thing at that point. Maybe I would have, if I hadn’t discovered a frog someone had been using for target practice, down at the local pond. He’d healed but you could still see the BB under the skin, roll it between your fingers when you palpated the abdomen. And those pellets were made of lead. Toxic stuff. This frog had survived the initial gunshot, but the shrapnel inside might kill him yet.

So I wasn’t just curious, this time. Now I was being downright noble. I would heal the poor thing. I would remove the bullet. But cutting into an active frog would only compound one cruelty with another. No, first I’d need to anesthetize the little guy.

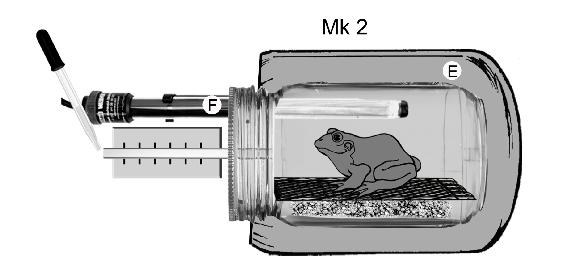

Canadian frogs hibernate, as it happens. As it also happened I’d upgraded my metabolism chamber, added new Drano-proofing features and—more to the point—temperature control. Metabolism Chamber Mk. 2 was jacketed in the blue gel that fills freezer packs (E): pop it in the freezer until it hardens and you’ve got a nice subzero environment when you take it out. Use an aquarium heater (F) to control temperature as desired.2

I put my patient in the fridge for a while to get him in the mood, then slid him into the chamber and gradually lowered the temperature until the little guy was out cold. I cut the teensiest incision in his belly, just big enough to remove the pellet. It popped out easily; froggy barely even twitched. I brought him slowly back up to ambient, transferred him to a private terrarium for recovery. Soon he was hopping around as if nothing had happened. It was one of the proudest moments of my young life.

How was I to know that frogs get frostbite?

He started chewing his digits. I didn’t worry at first—lots of people chew their nails, after all. The difference is, most people don’t chew their fingers to the bone; this frog was skeletonizing himself, chewing flesh that had frozen and gone necrotic. It was looking bad.

Not wanting another horrible death on my conscience. I took him back to his pond and set him free. When I last saw him he looked perfectly content, sitting in shallow water on hands and feet of barest bone.

I’m sure he pulled through, though. Yeah. Let’s go with that.

Eventually I outgrew basement science and graduated to the real kind, where—thankfully—my kill rate dropped to zero once I hit grad school. (It spiked again briefly years later—if you’ve read the snake-gutting scene in Echopraxia, you’ve caught a glimpse of my ill-advised 2006 post-doc in genetics—but that was an anomaly.) And while I’ve since taken in more than my share of wounded and/or brain-damaged creatures, it’s been a long time since I’ve been the cause of such carnage.

Just for the record, I’d like to keep it that way.

1 I wasn’t smart enough to invent this apparatus on my own, in case you were wondering; I got the plans from Dr. Mengele’s Book of Science Activities for Young Boys, or some such title.

2 Now this, I did come up with on my own.