Nowa Fantastyka Dec 2016

Blog remix Jan 18 2017

Back when I was in grad school, I built an electric bong out of Erlenmeyer flasks, rubber stoppers, and an aquarium air pump. It fed into an inhaler that dangled over my bed like the deployed O2 mask of a falling airliner—right next to the control panel that ran my planetarium, a home-built device that projected stars and nebulae and exploding spaceships across the far wall. The stars actually moved in 3D, came right out of the center of the wall and spread to the edges at different speeds. Wisps of nebulae would undulate as they streamed past. Planets swelled across the screen, rotating. Not bad for a contraption built out of old turntables and light bulbs and half-melted plastic peanut butter jars stuffed with colored cellophane. You haven’t lived until you’ve got stoned and sailed through the Trifid Nebula to the strains of Yes.

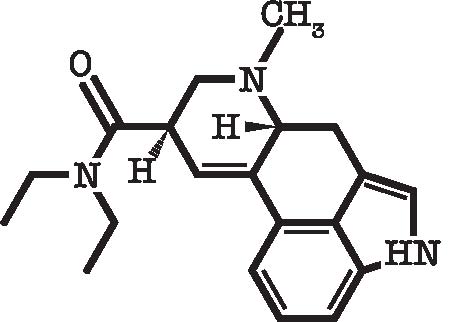

Back then I was what some might call a “pothead.” And yet I never progressed beyond cannabis, never even dabbled in hallucinogenics.

In hindsight, it was a serious deficiency in my upbringing. Two thirds of those who’ve used psychoactives describe the experience as among the most spiritually significant of their lives. MRI studies show that LSD wires together parts of the brain that normally don’t even talk to each other1. It deconstructs one’s sense of Self right down at the neuronal level, and you know me: I’m flat-out fascinated by this stuff. So why, half a century of my life already spent, had I never tried LSD?

About a year ago I voiced this regret to a friend of mine, a guy I’d first met when he was just a bright-eyed adolescent asking me to talk to his high-school English class. Somehow he’d grown up in the meantime (I myself remained utterly unchanged); now he has a PhD under his belt, teaches at a local university. He took pity on me; a few months back he slipped me a couple of confetti flakes laced with hallucinogenic goodness.

I knew people who swore by the stuff. I also knew people who admitted that under its influence they’d wandered down the middle of busy streets, or tripped along the edges of the Scarborough Bluffs with a strange sense of invulnerability. I was curious, but I had no great desire to end up as a puddle of viscera at the foot of some cliff. I chose a more controlled approach. I called on my buddy Dave Nickle to ride shotgun.

“Three ground rules,” Dave told me upon his arrival. “First rule: You don’t leave the house. Second rule: When you break the first rule and leave the house, do not go into the road. Third rule: when I say Stop what you’re doing right now, you stop doing whatever it is you’re doing. Right. Now.”

I sucked the first tab to mush. Not much happened, beyond a growing impatience at Dave’s rate of progress through the game of SOMA he was playing while we waited for things to get interesting. So I popped the second one after about an hour.

Things got interesting.

It kind of sneaks up on you.

At first it just feels like being drunk or mildly stoned: light-headedness, a loss of somatic inertia, but without any nausea or hypersalivating spinniness. After a while the edges of vision start to look a little like those optical illusions you see in Scientific American—you know, those moiré patterns that seem to be moving even though you know they’re not. The effect starts at the edge of vision, spreads inward to the center; suddenly the folds in my bedcovers are rippling like rivulets in an alluvial delta. Plunging my splayed fingers down onto the bed stops that movement dead, for a few moments at least; my fingertips somehow anchor the material, force it to behave. But then those rivulets start eroding around them, as though my fingers are sticks in a stream: not stopping the flow, only reshaping it. No matter how hard I stare, no matter how intense my focus, I can’t get them to stop.

I’m a ghost for a while, my body as ethereal as mist. I think I know why. They’ve done experiments where you watch someone say a word, but the word you hear doesn’t match the speaker’s mouth movements. The brain reconciles that conflict by hearing different sounds than those actually spoken, sounds closer to what the mouth seems to be saying.

I think this is something like that.

I feel incredibly weak. I just know, down in the gut, that I lack the strength to even lift my arm off the bed. And yet I do more than that: I rise up off the bed entirely, go into the next room, do a few chin-ups. How does the brain reconcile that? How does the wetware square you’re too weak to move with you’re moving? I think it’s decided that I must be massless. I lack the strength to move anything; I am moving; therefore I must be made of nothing. I become a ghost, utterly free of inertia. I feel the truth of that right down in my diaphanous bones.

There are different cognitive modes, mindsets as distinct as delight and dementia. They do not overlap. Sometimes the hallucinations are vivid and undeniable but my mind is stone cold sober: I can look hard at the bright static image on the screen, see beyond doubt that the things there are moving—and yet know intellectually that they’re not. I report the hallucination with clarity and concision, comment both on what I see and the impossibility of it, as though I were dictating the results of an autopsy. My senses are lying, but my mind is clear; I am not fooled.

Other times, though, I don’t even know if this thing called “I” even exists. It seems to—to spread out across the room, as though I’ve become some kind of diffuse neural net hanging just below the ceiling. It’s not a visual hallucination—this mode’s pretty much hallucination-free except for a ubiquitous heat-shimmer effect that makes everything ripple2. This is a more visceral, intuitive sense of being distributed. Every now and then some ganglion in the net lights up at random, and the system blurts out whatever words that node contains.

It is at one of these times that Dave sadistically engages me—apparently he thinks there still is a “me”—in political discourse. (I believe this is known in the vernacular as “Harshing the Buzz.”) Somehow we’re talking about the US election, and the distributed neural net wants to say: I don’t think Trump really believes all that shit he says about Muslims and Mexicans. I don’t think he believes much of anything; after all, he was staunchly pro-choice before he started running on the Republican ticket. I think he just plays to the crowd, says whatever gets him the loudest cheers. The real danger isn’t so much Trump himself, but the fact that his victory has unleashed and empowered an army of bigoted assholes down at street level. That’s what’s gonna do the most brutal damage.

This is what Neural Net Watts is trying to say. But the nodes light up at random and I think what comes out is more like “Aww, I don’t think Trump is so bad . . .” This horrifies whatever vestigial part of me still exists; I try desperately to clarify so Dave won’t think I’m a complete asshole, but the neural net wonders “Are these words just random network discharges with no intrinsic meaning—or, have the drugs stripped away my humanitarian facade of decency revealing the true, Trump-defending monster within?” The neural net wonders how much of this it said aloud.

Some, at least. Because from a very great distance, Dave is saying “Don’t sweat it, dude; I’m not hearing anything you haven’t said before.”

We watch the back end of 2001: A Space Odyssey. I’ve seen that movie at least 50 times; this is the first time I’ve ever seen it while high. I am entranced, more entranced than I’ve ever been before by this masterpiece. Every frame, every sound is a revelation packed with new meaning. Five minutes after the credits, though, I can’t remember what any those meanings actually were.

I want to watch Alien next, or maybe Eraserhead. Dave guides me gently toward something less potentially-traumatizing: a fan-made episode of “Star Trek” posted on YouTube, with cardboard sets and twentysomething amateurs playing Kirk and Co. Apparently there are several of these: Star Trek Continues, they’re called collectively. This episode is a sequel to “Mirror, Mirror”. Evil Spock’s goatee looks like someone glued a shoehorn to his chin.

It’s like watching a high-school play put on by students from my ’73 shop class. The drugs do not help at all. Alien would have been far less terrifying.

I cannot look away.

Twenty minutes of preflight research have uncovered the fact that tomatoes apparently taste awesome when you’re high. Many have attested that the taste of a psychoactivated tomato is orgasmically intense. I have laid out an array of tomatoes, from tiny grape to humungous vine-ripened. At the height of my powers, I devour them all.

Meh.

In a blinding flash of insight, I understand why people always sound so trite when describing acid trips: because language evolved to describe the pedestrian realities of everyday perception. The psychoactivated brain is wired up differently; there are literally no words for the way it parses reality. These insights are literally untranslatable. Of course forcing them into words turns them into lame, trite clichés.

I try to explain this revelation to Dave. It comes out in a torrent of lame, trite clichés.

Coming down now. The light-headedness persists, but the shape of the world has congealed back down to its baseline state. Caitlin has returned from work; apparently Dave has been texting updates to her all day. I study the tendons in my hand as he provides my wife an executive summary. “It went okay,” he says. “There was one point where he started seeing bats everywhere, but there actually were bats, so that was fine.”

It’s been six hours, in and out. I thought it would last longer.

We release Dave from his duties with hugs and thanks and a bunch of uneaten snacks I’d stockpiled against a case of the munchies that never materialized. He is a good friend.

The last of the buzz is fading. The BUG is glad that I did not hurl myself in front of a bus. We climb into bed and boot up our laptops and discover that Leonard Cohen has died.

I hope that’s just a coincidence.

1 I think these might be the source of those clichéd Aauugggh your face is melting! depictions of drug use so favored by the Just Say No crowd.

2 http://www.pnas.org/content/113/17/4853