A lot of rubbish has been talked and written about the way a golfer should swing the club back from the ball. There have been those who advocated rolling the wrists, those who advocated holding the clubface ‘square’ as long as possible, and those who swore by hooding the clubface during the takeaway.

The ‘squares’ are the ones on the ball, but the trouble is that they don’t always define what is truly ‘square’. The golf swing combines an arc and a plane. How, then, do you get ‘square’?

The answer is by swinging the club away from the ball in one coordinated movement – without any independent action of any part of the body, especially the hands and arms.

Prove it for yourself as follows. Take your aim and set up correctly for a full shot. Now, without rotating your hands and arms or consciously cocking your wrists, but making the club as near as possible an extension of your left arm, turn and tilt your shoulders slightly and let your arms swing back in concert with this movement. The club will have moved back inside the target line – there is no other place it can go if you have set-up and turned properly. And the clubface – where will it point? Not at the sky – which would have happened if you had rolled your wrists clockwise. Not at the ground – which would have happened if you’d held the face down or hooded. It will be pointing more or less forward – at right angles to the arc of your swing.

This is ‘square’, as you can very quickly prove by turning your shoulders back to their original position, when the clubface will return squarely behind the ball.

And that is the correct takeaway.

Turn your body, cock the wrists

I had played golf from childhood – and had a club in my hand from the time I could stand up. I suppose, at 15 or 16, I could get round Lindrick on occasions in under 70, but at other times I would have to walk in from the course because I had run out of golf balls. I was gifted in the sense of being able to hit the ball because I had grown up with it and had the chance of watching fine players in the area – Arthur Lees, Frank Jowle, Johnny Fallon and, of course, my cousin Jack. So when Willie Wallis (my boss and the head professional at the Hallamshire where I got my first job as assistant) said to me: ‘You must turn your body and use your lumbar muscles and you must cock the wrists,’ I took notice of it.

Today I will tell pupils they must turn the body because you have to do that to get the clubhead swinging from inside to inside, and you must cock the wrists otherwise the club will follow the body too much. What Willie was saying was similar to what I am saying today. The difference is that I explain it, whereas he didn’t.

Keeping it simple

You are now taking great care to pre-programme, as far as possible, correct impact through your grip, clubface aim, ball position, and body alignment and posture. All that remains for you to play the best golf of which you are capable is to swing the club on a plane and in a direction that transmits your address ‘geometry’ to the ball, while also generating sufficient clubhead speed to propel it the required distance.

How do you do that?

Because the ball is lying on the ground to the side of you, the answer is with an upward and downward swinging of the arms combined with a rotational motion of the body.

How much swinging relative to how much body motion? How ‘steeply’ up and down should your arms swing relative to the ‘aroundness’ of your body motion? Which drives what – the arm swinging the body rotation, or the body rotation the arm swinging? Where does the power come from – the swinging motion of the arms or the rotating of the body?

All of those questions, and all others like it, will quickly become moot if you will simply do as follows:

Swing your left arm directly back from the ball, allowing it to move progressively upward and backward – i.e., to the inside of the target line – as a natural response to the rotation of your shoulders around the axis of your spine.

Can the golf swing really be that simple?

Well, if you ever reach the point of feeling that your chief golfing problem has become ‘paralysis by analysis’, forgetting everything but the above concept of backswing motion might delightfully surprise you.

Wind up – don’t lift up

When teaching, I get pupils to finish the backswing completely, before starting the downswing, by asking them to point the clubhead consciously at the target before starting down. This virtually ensures a full shoulder pivot and a complete wrist cock.

Under and out of the way

I have often asked myself what is common to all good strikers of a golf ball. The only thing I can find which they all seem to do is that they hit under. By that, I mean that the right side relaxes and swings under a taller left side through the ball. This means that in the hitting area the shoulders are tilted, and yet the left hip is turned to some extent towards the target so as to get the body out of the way sufficiently to allow the hands and arms room to hit through.

Let me now try to define the downswing. To allow the right side to swing under, the first thing to do in the downswing is to move the hips laterally to the left. This can only be achieved by good leg action. This is the under part of the swing. The start down with the lower half of the body will have brought the hands and arms down to hip height, leaving the shoulders behind.

From here we concentrate on the out of the way part as we cut loose with the hands and arms. The head, I hardly need to say, must remain still during all of this. Indeed, if there is a secret to hitting under and past the body it is to keep the head behind the ball until the ball is in its way.

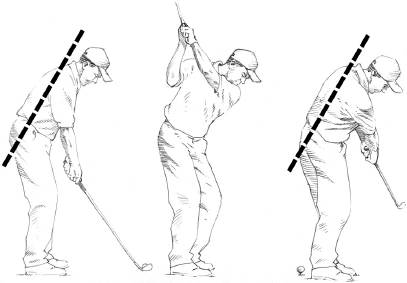

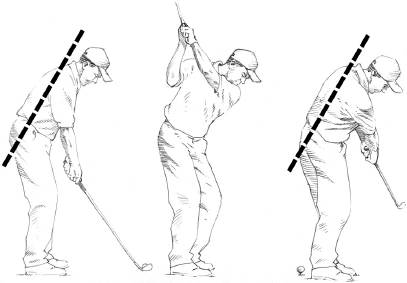

The classic golf swing requires little more than ‘two turns and a swish’. Note the spine angle remains constant.

Don’t be a statue!

Are we not getting far too position-conscious and forgetting the all-important thing – to swing the club?

We have had in the recent past a spate of golf books, full of positions that dissect the golf swing. It is important to remember that the players shown in this way swing through the positions you see in the books, and I suppose never really feel the different positions you see when looking at the pictures.

All too frequently we see potentially great golfers putting themselves into that late hitting position of a Hogan and a Snead (or today, an Els or a Woods). This sort of thing is of no value whatsoever! In fact, I would say it is harmful, in that anyone who tries to put himself into this position has so obviously missed the reason why the great players are able to swing this way.

The wrists are not consciously held back in the downswing until the last moment. This really is too difficult to do. Learn to swing and swing correctly, and the wrists will uncock at the right time. I get the impression that many of our young players are making a conscious effort not to let the clubhead work in the hitting area. In other words, they are so keen on late hitting that they are never actually using the clubhead at all – despite the fact that hitting is surely the most natural thing to do with the clubhead, certainly more natural than trying to hold the clubhead back!

Grip, stance and pivot should allow for the hand and wrist action to be absolutely natural, and not forced in any way. If you feel you have to consciously hold the clubhead back, then there is something wrong and you are certainly not swinging.

In the past we have seen many unorthodox swingers playing great golf. The very fact that they have been swinging has helped them in the groove. I feel sure these players have never become too much bogged down by position. If you are in a wrong position, then certainly try to swing through a better one. But whatever you do, don’t try to put yourself into a better position.

A golfer’s waggle usually gives the show away, proclaiming whether he is a swinger or not. The non-swinger is so stilted that we know he is going to go from one position to the next, and never swing the club at all.

The top of the backswing and halfway down positions seem to be the most sought after. How often do we see a player admiring that late-hitting, halfway down position he has put himself into! He can feel where he should be. I venture to say that the finest players never feel this position; they feel a much more complete thing, that of swinging the clubhead through the ball to the target. We all freely discuss our golf swings but how many of us have swings, or have we just a set of many positions?

Timing – the elusive quality

Most modern books on golf have abundant and arresting action pictures, showing positions in the backswing, downswing, and followthrough. Perhaps it is this factor, as much as any other, which causes us to think of a swing in three distinct parts. To do that may be well enough, except that sometimes it can lead to the loss of that essential element in our swing known as timing.

What an elusive word that is in relation to the golf swing! One hears, so often, ‘my timing was a little bit off today’ when some unfortunate has had a bad day; and, as it happens to so many of us, it is perhaps not a bad thing if we try to be more specific and pinpoint this gremlin of bad timing, which can strike at the best of swings.

When it happens to me, I try to remember one thing, and often it helps; it is this: ‘Remember, I want my maximum speed at impact – not before’.

If I can let this really penetrate my mind, it is the easiest way to cut out that quick snatch back from the ball, or the snatch from the top. When I see it in pupils, I find myself saying: ‘don’t forget it is the ball you are hitting, not the backswing.’ Put another way round, what I could say is: ‘wait for it’, but I think it is easier to wait for it if you know what you are waiting for!

Distance is clubhead speed correctly applied

Let me remind you that ‘correctly applied’ means:

Never forget that no matter how high your clubhead speed, the greater the error in any one of those angles, the less useful distance you will gain.

Straight enough

The left arm is the radius of the swing arc and it must maintain that radius. To do this it need not be ramrod straight, in the sense that Harry Vardon meant when he said he loved playing against opponents with straight left arms. It must be straight enough, without being stiff. In any case, even if the left arm is slightly bent, it will be straightened out in the hitting area by centrifugal force.

The beginner, and he who aims to improve his game, must have faith here. He must believe something quite simple; that there is no need to do any conscious squaring of the blade in the downswing, or in the hitting area, with the hands. The hands should be left free for hitting the ball. The correct downswing action from the top, in the correct sequence, will take care of the blade of the club as it swings through the ball.

It really does all depend upon how the body is wound up and unwound. The hands and arms need to swing freely from the hub of the wind-up. Wind-up, then unwind, and swing the clubhead while you are doing this by a free use of the hands and arms. This type of action works for every club in the bag, allowing the loft on each to do the work as necessary.

The right elbow

Ninety-nine percent of floating right elbows – the ones that stick up or out like a chicken’s wing – are caused by an incorrect pivot. If you tilt your shoulders instead of partly turning them, and take your hands back ahead of the clubhead, then you will get a floating right elbow.

Controlling the elbow won’t necessarily put the thing right, since it is caused by a combination of pivot and of wrist action following the pivot, which leaves the clubhead behind in the backswing. You cannot correct it by getting the clubhead on its way back first, so that it leads the elbow into the right position, which then feels strong while you turn.

You could, of course, hit good golf shots with a floating right elbow, as long as the elbow gets into the right place to hit the ball. But only a right relationship between hands and body can put you into the right position in the easiest way.

When teaching people, there is quite a simple general rule I follow: in both cases, floating right elbow and too-tight elbow, I use what sounds like a local independent variation merely to wipe another one out, in its effect when the player tries to do it. You tend to get a floating right elbow if you leave the clubhead behind your hands. If you then try to start back clubhead first, you often cure it.

Other things being equal, of course, faults can come from both variations. If I drag the clubhead back, that’s when I float it; if I start the clubhead back too much ahead, I go flat.

If you don’t get the clubhead moving on the way back, then you can’t get back to the top of the swing without moving the right elbow out from the body; and the delayed clubhead thus nearly always leads you to a steep position. You can easily spend five minutes explaining this to a player; and he can easily follow this and see how it all works.

There are actually thousands of people with this sort of trouble, because those who have read about and studied the game have been told so much to ‘take the club back in one piece’. Trying to do just this, if it is misunderstood, can lead the player straight into a floating right elbow!

With this particular fault, as with so many others in golf, we come back to just one basic thing. May I repeat myself once more and say it again: The relationship between your clubhead, your hands and your body is vital. If you get the right relationship between your clubhead, your hands and your body, you will never get a floating right elbow.

Don’t forget your hands

Nick Faldo’s swing changes in the 1980s centred around a few key elements. He widened his stance so that his legs would stabilize and support a more rotary body action. He then focused on winding his body over a more passive leg and hip action, which created resistance – in effect, energy – that he would then use to drive a more powerful downswing. The arms swung in response to the body motion, whereas in his swing of old the hands and arms dominated the action and the body just went along for the ride. Basically, Nick went from being a very handsy player to a more body-controlled, passive-hands player.

That was just the ticket for Nick, but overemphasis on body action is dangerous territory for the average golfer because it assumes you have a great hand action and, to be frank, most club golfers suffer from a lack of hand action rather than too much. That’s why I often prefer to use the arc of the swing to get the body moving. Once you get the correct in-to-in picture of the swing path, your body will clear out of the way virtually automatically, creating the proper release of the hands and thus the clubhead through the ball.

You ‘aim’ the clubhead at the top as well as at address

If your clubshaft parallels your target line at the top of the backswing, the club is ideally ‘aimed’ to swing back through the ball along the target line.

If your shaft is angled left of the target line at the top, there will be a tendency to swing the clubhead across the line from out-to-in and either slice or pull the shot. Conversely, if the shaft is angled right of the target line at the top, there will be a tendency to swing the clubhead from in to out across the target line and either hook or push the shot.

Understanding swing plane … in simple terms!

The plane on which you swing is established chiefly by your address position. As you stand to the ball comfortably and squarely, neither cramped nor reaching, your left arm and the club form a more-or-less continuous straight line. The angle of that line, relative to the vertical, is the ideal plane on which to swing the club up and down with your arms.

What you are aiming to do, in golfing terms, is to shift your right side out of the way in the backswing and your left side out of the way in the throughswing, so that at the moment of impact the club is being swung freely by your arms with the clubhead moving straight through the ball, along the target line.

Numerous enlightening books and articles appear describing varying aspects of the golf swing. But there are some aspects that rarely find their way into print. Plane, for example. I intend here to single it out for the special attention it merits, if rarely attains. Why is plane so important? Because if the plane of your swing is correct, the angle of attack on the ball is correct. That sounds difficult. Let’s look closer.

Generally speaking, a swing in the correct plane gives you a fairly flat bottom to the swing, which is what we want in order that the power we are unleashing will proceed directly through the ball. The same amount of power, or more power, applied more steeply or from an incorrect plane, cannot hope to hit the ball so far.

My idea of a correct plane is one in which if, at the top of the backswing, we extend the line from the left hand to the left shoulder downwards, that line should then approximately aim at the ball.

It is obvious, then, that the plane of the swing will vary with the distance one is standing from the ball. This in turn varies with whatever club we are playing. For example, one stands close with a 9-iron, because of its short shaft; and the resulting swing is much more upright than the swing with a driver.

There is no real problem with this change of plane, though; for from the player’s angle it is purely automatic and should merely vary directly with the length of club used.

Now, in the correct pivot in the backswing there is a certain degree of shoulder turn, linked with a certain degree of shoulder tilt. One can soon deduce how a swing with too little downward tilt of the left shoulder, and too much turn, will be too flat. Similarly, one with too much tilt, and not enough turn, becomes too upright.

Each swing, though, produces its own characteristics. A ‘too upright’ arc usually makes for better iron play than wooden club play, since these iron shots are hit on the downswing. Correspondingly, a ‘too flat’ swing often works very well with the woods, but is of little value for iron shots, since these are then hit nearer the bottom of the arc.

The present vogue is to aim at an upright swing – which I suppose I would prefer to a flat one. But why not swing in plane – which will then be the right degree of uprightness for all shots?

Don’t spin your shoulders

If you spin your shoulders too early in the downswing, it throws the club outside the ideal swing path which means you’re right on track for a pull or slice. This is perhaps the most common fault I see at club golfer level.

If that sounds familiar, think about how you swing your hands and arms down from the top. I’m reminded of the great Harry Vardon, six time Open champion, who said that as he changed direction from backswing to downswing, he felt his hands swung down to hip height before his body even began to unwind. In reality, he combined the perfect arm swing with the ideal body rotation, but his feeling was one of swinging the arms down first and this is a swing that that would definitely help you if you slice. It encourages the hands and arms to play a more dominant role, swinging the club down into impact on the ideal path and plane.

Don’t let tuition destroy your natural rhythm

As a teacher I’m forever conscious of the fact that tuition must never get in the way of the natural rhythm in a golfer’s swing. I remember teaching Seve at Wentworth in 1979 and thinking: ‘I’ve got to be careful here.’ He had such wonderful rhythm that I didn’t want to tell him anything about his swing that might upset it. So all of my advice to him was in consideration of that fact.

When Seve was playing well there wasn’t an ounce of tension in his body. I believe that some of the problems in the 1990s stemmed from the fact that he’d become perhaps overly concerned with techniques and swing thoughts, which has never quite been his style, and thus taken away some of that natural softness and impeded the free-flowing motion of his swing.

This is a danger for any golfer. Whenever you get taught something new, the first instinct is to tighten-up and that process usually starts with the grip. You must be aware of this and avoid tension creeping into your hands. Never lose the gift of being able to swing the club freely. Keeping your grip soft will almost certainly help. As Peter Thomson used to say: ‘Always grip lightly because you’ll instinctively firm up at impact anyway.’ That’s not a bad philosophy to bear in mind whenever you’re trying to make changes to your swing.

If you wind yourself like a spring …

I like to compare body action in the golf swing to the winding and unwinding of a spring. Think of it this way and you will realize how important it is that the bottom half of the spring should resist the turning of the top half, in order to increase coiling (and thereby power).

The feeling should be one of staying relatively still, but ‘lively’, from the waist down, while your torso turns around the axis of your spine and your arms and hands swing the club back and up so that it ultimately points parallel to the target line. The left leg will give a little, turning in towards the right, and the left heel will usually be pulled rather than lifted off the ground. But the effort should be to prevent, rather than encourage, such movements – while making sure your shoulders turn as your arms swing the club back and up.

… automatically you will let it all fly

Create sufficient torque with your upper-body backswing wind-up and you cannot help but release it into a powerful throughswing. As your legs and hips win the battle of the opposing forces, and pull spring-like towards the target, swing your arms straight down before your shoulders spin. Never do anything to inhibit a free arm-swing.

Keep your head down? Forget it!

When I was on the instruction panel of the American magazine Golf Digest in the 1960s they carried out a survey of the leading 50 money winners on tour. They photographed each golfer hitting shots, with a grid pattern positioned behind them so it was possible to monitor their head movement during the swing. Of these, 48 of the 50 golfers moved their head to the right in the backswing. Some moved more than others and two golfers remained centred. But, not surprisingly since these were all good players, none moved to the left.

The obsession among some club golfers to keep the head down has kept me busy for 50 years. It’s like strapping a straightjacket on to a golfer; it restricts a full, free turn, so essential for both power and accuracy.

So if ever I hear of a golfer whose main swing thought is to keep their head down throughout the swing, the alarm bells ring in my head. In any good swing there is invariably a certain amount of lateral movement of the head and body. So long as this body action is harmonized with the hand and arm action, it is allowable and in many cases desirable for there to be a degree of lateral movement.

Careful of some other clichés

Let’s punch holes in a few more of some prime ‘book’ clichés:

‘Go back slowly’: This is nothing short of an invitation to disaster. It leads to moving rather than swinging the club back, in a motion completely lacking in rhythm. If you go back at the pace that the slow-back proponents suggest, you have got to control the club every inch of the way, which, apart from anything else, is too much of a mental exercise.

What you should do instead is set the swing off smoothly at a pace that will enable you to come down quicker than you go up. I find most players swing at the correct pace when they remember they want their maximum speed at impact.

‘Tuck in the right elbow’: A right elbow flying away from the body is usually caused by a steep tilt of the shoulders in the backswing, rather than a combined tilt-turn. It is equally wrong, however, to suggest – as some teachers still do – placing a handkerchief between the right elbow and the body and keeping it there in the backswing and downswing. The right elbow will find its correct position if the shoulder turn and the arm swing are correct.

‘Follow through’: Making a conscious effort to follow through nicely when the rest of the swing is thoroughly bad leads to nothing but confusion and frustration. The initiation of the downswing completely commits you all the way to and through the followthrough. So, if you think your followthrough is bad, look for something wrong much earlier – possibly your grip, set-up, backswing or the way you start your downswing. Remember that a correct followthrough is the result of a correct start down.

Sweep those arms down and through

The action of the arms is the most neglected area in golf instruction. There have been ‘hands’ methods, and ‘body’ methods, but the fact is that, whatever method he hung his hat on, every good golfer in history has swept the club through the ball fast and freely with his arms.

When I am teaching I continually find myself using some phrases over and over again to player after player. Since these would seem to be the ones I have found most helpful to the most players, it may be worth repeating them yet once more. They are:

How – and what – to practise

I assume that the fact that you are reading this book means you want to improve your golf. I further assume that you want to improve badly enough to be prepared to give some time – even time that you would normally have spent playing – to practising the game. Some of us are ‘naturally’ more talented golfers than others, but all of us need to practise to develop and hold our full potential.

I have spent a lot of time teaching, so I know a fair amount about the habits of the average golfer in terms of their approach to practice. And what has come home to me is that he has a great deal to learn, not simply about the technicalities of golf, but about the sheer mechanics of practising it. What seven out of ten golfers do when they go to a driving range, or down to the club with a bag of balls, may be exercise, but it isn’t practice.

Let us start, therefore, by defining practice. It has three distinct forms.

The first and absolute primary form of practice you do at home sitting in an armchair, or driving the car to work. You can do it with your brain, and it consists of thinking through the cause-and-effect of whatever you were doing the last time you played golf. From here, still strictly on the mental plane, you decide through a logical reasoning process, not guesswork, exactly what you will be trying to achieve the next time you practise. Ideally, these thought processes should be based on lessons you have been taking from a professional in whom you have confidence. There is no substitute for personal tuition – for advice tailor-made for you as an individual. The vitally important thing, however, is never to practise until you have a clear picture of what you are trying to do.

The next form of practice is the physical execution of what you have planned mentally. This is swing-building and game-improving practice, and we will look at it in detail in a moment.

The third form of practice, which all good players do, and which I’d like to persuade you to do, is the prelude to any important round of golf. It isn’t practice in the previous sense, because you are not trying to rebuild your game (or at least you shouldn’t be). What you are trying to do, with anything from 10 to 50 shots, is to tune up the game you possess on that particular day; to loosen muscles, to get the ‘feel’ of the clubs, to bring the clubface into the ball squarely and solidly and thereby boost your confidence for the ensuing round. And to find one workable swing thought for the day. This is the form of practice few club players bother to make the effort to do, but which is indispensable if you have serious golfing ambitions.

Having defined practice, let us now get back to the actual techniques of its swing-building form. Once you get to the practice ground with cause, effect and treatment all clearly in mind, don’t worry too much about where you hit the balls – especially if you are making a major swing change. Your fault will have been grooved, and the action incorporating it will probably feel comfortable. The cure might at first feel very strange, but you must persevere if a lasting improvement is to be made. If no improvement can be made over a reasonable period, rethink the problem or go back to your golf teacher.

Next, before you even draw a club from the bag, pick a definite point of aim. It doesn’t matter what it is or how far away it is, so long as you can focus upon it easily.

Now, take out not your sand-wedge nor your driver, but your 6-iron. This club represents the mean average between the extremes of loft, shaft-length and power. It is the ideal swing-building club.

With the 6-iron in your hand, the point of aim in your eye, and your swing objectives crystal clear in your mind, ‘break down the adhesions’ with a few easy – but not careless – shots. Right from the outset try to grip correctly, aim the club as the first step in setting-up and set yourself correctly to that clubface alignment.

As you move into the session, try with every shot – and I mean every single shot – to do what your preliminary analysis has told you will give you a more solid strike or a straighter flight. Stick to your guns on this long enough to determine whether your mental assessment and cure was right. If it was, keep on practising it only as long as you have plenty of mental and physical energy and enthusiasm. Then plant the relevant ‘feel’ firmly in your mind for the next actual game you play.

My method of doing this sort of work – and it is work mentally and physically – would involve basically a 6-iron, a hundred balls and as many one-hour spells a week as I could manage. Even if I were a weekend player, I think I would be prepared to sacrifice actual playing time in order to make a lasting improvement. For instance, if I normally played 12 hours a week, I would play perhaps six and practise the other six.

If your assessment and cure are proved wrong after fair trial, do not give up, start experimenting at random, or lose your temper and pop off balls like a pom-pom gun. Take a rest. Go and sit down somewhere and think it all through sensibly again.

The flight of the ball tells you what you are doing, in your grip, in your swing line relative to the target line, and in the angle at which your club is attacking the ball. Use this information at all times. Therein lies the only ‘secret’ of golf.

A lot of resolution is necessary to carry through this kind of programme, as it is to stick with any change in method when actually playing the course. Until the new system works, rounds played can be less than satisfying (which is a good reason for not playing too many!). If it is essential to try to play well on occasion while in the middle of changing your swing, obviously a compromise will have to be made.

I know only too well that weather and golf club facilities in Britain are against consistent and studied practice, but I am equally sure that if a golfer is keen enough he will find a means. As a last resort, he can erect a golf net at home. For years I used to smash golf balls into a net in my garage, and this is very valuable swing-changing practice, first because you haven’t got a result to worry about, and secondly because there is no one to see how badly you are hitting the ball. If you are that keen but don’t have the facilities to put up a net, try knocking lightweight plastic balls off an old doormat. Anything you can do to build up your golf muscles, to ‘groove’ good actions, to keep swinging, must eventually pay dividends.

At the very worst, try every day to swing a club at home for a few minutes – concentrating on what you would be doing if you were hitting balls.

One more important point. There is yet another type of practice – the kind one does on the course in preparing for a tournament. Many people go about it wrongly.

Never play more than 27 holes a day in practice, especially the day before an event. It is essential to conserve both energy and enthusiasm for the actual competition. Very few world-class golfers ever play more than one round a day in practice.

Don’t play sloppily in practice rounds. Try to hit the ball solidly, and don’t be frightened of scoring well. A good practice round builds confidence.

Give yourself time to take note of the course and your own play. You need two or three extra balls handy to play extra shots, especially bunker shots, chips and putts, hitting them from where you think you will have to hit them on the big day. Take particular note of the clubs you play, especially if the weather is fair. In windy or wet conditions, of course, your practice round estimates may have to be revised.

Finally, although you may use your practice rounds to loosen up and make final swing adjustments, never fundamentally change your method during practice rounds. You are stuck with what you’ve brought with you. Try to make it work as best as possible.

This happens in every good golf swing

Stand facing any good golfer and watch the space between his hands and right shoulder during the downswing. You will see that it widens like lightning. Then watch any golfing friend who slices the ball repeatedly. The space between his hands and right shoulder will not widen as fast, because he swings his body rather than his arms. The speed at which all good golfers widen this angle is proof positive that, although the lower body initiates the downswing, leg and hip action must always be married to a fast, free arm swing.

Baseball analogy helps keep your swing on plane

One last thought, which may ring a bell with one or two readers. I think golf is very akin to baseball – in this way; in baseball a player swings in plane with the flight of the ball as it comes towards him. In golf, all we have to do is swing in plane with however far away we are from the ball, which partly depends on what club we are using. For any shot and any club, the plane most likely to be easiest really is that ranging straight up from the ball just over the shoulders, as you stand to address it for the shot.

In any good golfer’s swing, the space between the bands and right shoulder widens ‘like lightning’ in the downswing.

Try ‘two turns and a swish’

Golfers, I am afraid, sometimes like to make the game more complicated than it actually is. My simple definition of the golfing action is ‘Two turns combined with an arm and hand swing’. And I am often accused of oversimplification when I use this phrase.

Well, here’s a suggestion for you. If your game isn’t what you would like it to be at the moment, and especially if you feel confused and snarled up by theory, play your next three rounds strictly on the basis of ‘two turns combined with an arm and hand swing’.

Don’t think of the backswing as a set of complicated and separate movements, but simply as the first turn. Think only of moving your right side out of the way as your hands and arms swing the club back and up. Simplify your downswing likewise. Forget all the stuff about head, hips, late hitting, and what-have-you. Simply picture your downswing as the second turn, moving your left side out of the way as your arms and hands swing the club down and through the ball.

If you have a decent grip and set-up, and can keep your head reasonably still and your feet firmly on the ground in the backswing, approaching golf this way could do wonders for your score.

You will very quickly learn that the swing really isn’t a complicated movement, and that the ‘secret’ of golf lies in coordinating the turns with the actual swinging of the club – not in a series of geometrically exact, deliberate placement of the club in certain ‘positions’.

Find a way to turn … even if it’s not exactly like Ernie

Ernie Els achieves a massive upper-body turn without lifting his left heel. The hips don’t turn much, either, so together that creates a lot of resistance in the legs – the action of a supple man and a powerful hitter.

Most of you reading this will not be as supple as Ernie, but it’s important that you find a way to turn your body, in whatever way is appropriate for you personally. For many, this means making certain compromises, such as lifting the left heel to ‘release’ the left side and thus make it possible to turn. You won’t generate as much resistance in the legs, but it’s better to do that than keep your left heel planted which might not give you the flexibility to make a sufficient turn.

On a personal note, currently 80 years of age, I can say from experience that it is necessary to release from the ground in order to complete the full upper body turn.

Starting down

The correct start down begins in the lower half of the body – the legs and the hips. That is why telling people to ‘stay sat down’ in the backswing, and to ‘get the left heel down first’ in the downswing, is often good advice; doing so consolidates the anchor point of the feet, and starts the hips swinging back into and through the address position. This automatically begins to pull on the arms and hands and unwind them towards the ball.

Just as the swinging wrist-cock of the backswing ended with the actual cocking of the wrists, so the swinging uncock of the downswing ends with the uncocking of the wrists, as you unleash the power of your hands into the stroke.

Ball forward produces a knock-on effect

Placing the ball correctly opposite the left heel in your stance is essential for the longer clubs in the bag, especially the driver. It sets your upper body ‘behind the ball’ at address and helps establish the appropriate tilt in the shoulders – the right noticeably lower than the left.

Correct ball position also promotes good weight transfer and encourages the shoulders to turn into a more powerful position at the top of the backswing. This good work in the backswing enables you to unwind the body correctly in the downswing, providing free passage for the hands and arms to swing the club dynamically through impact on the optimum path for power. And with the ball being ideally placed in the stance, the clubhead meets it on the ideal angle of attack. It all adds up to the perfect recipe for long, straight driving.

Play to your strengths

Throughout the 1990s there were very few better drivers of the ball than Colin Montgomerie. His accuracy off the tee stemmed from an ability to cultivate a particular shape of shot – namely, the fade – and trust that shot implicitly on the golf course. He would aim down the left side and ever-so-slightly fade the ball into the middle of the fairway. This tee shot strategy is a great way of playing, because it eliminates half the danger on a golf course.

Think about someone who aims straight down the middle of the fairway. They have only to stray off line by half the width of the fairway to finish in the rough either side. Now look at Colin’s strategy. He aims down the left side and fades the ball. If all goes according to plan, the ball finishes in the middle of the fairway. If the ball flies dead straight, he’s in the left half of the fairway. And if he over-cuts it, he’s in the right half. His margin for error is twice the width of someone who aims down the middle with no particular shape in mind.

That’s called playing to your strengths, something all good players do.

For power and position, turn your shoulders ‘flatter’ than your arm swing

It is a common misconception, even among good golfers, that the shoulders and arms should move on the same plane in the backswing. Look towards the target from behind any top golfer making a full shot to prove to yourself that this doesn’t happen. If the arms are to position the club correctly in the backswing, and swing freely in the throughswing, they must swing up as the shoulders turn around. Trying to marry your arms to your shoulders introduces too much body action into the shot, at the expense of clubhead speed.

Everything you need to know about legs!

It is widely recognised that good leg action is essential to good golf. Unfortunately, few average players really understand what constitutes good leg action. In fact, there is probably as much confusion about this department of the swing as about any technical aspect of the game.

Most golfers know that they (the legs) must work, so many make a deliberate, conscious effort to get them to do so. This usually leads to trouble. It is, for instance, the main cause of the ‘ballet dancing’ that is so common a spectacle on golf courses around the world every weekend.

If you study the great players in action, and compare their movements with the swings of your friends, you will find that in most cases the good players, on the backswing, have considerably less movement from the waist down than do club golfers, but considerably more in the throughswing. This is a direct result of resistance, torque, spring-like coiling. The good player coils in the backswing against the resistance of his feet and legs. The release of this power in the throughswing results in strong, positive movements from the waist down as the spring ‘springs’. The poor player fails to supply the necessary resistance in his legs and feet. He dances around in such a way that there can be no build-up of torque, no coiling of the spring, in the backswing. Then, there being nothing to release in the throughswing, he is either stiff and wooden in his legs or collapses completely when he comes to hit the ball.

The golf ball cannot be struck powerfully and accurately with any action other than that comparable to the wind-up and release of a coil spring.

If the golfer will believe this, and work at it, he will soon realize that his feet and legs are a critical part of his anatomy. They are his contact with the ground, his platform, and their task is nothing more nor less than to resist – to anchor the end of the spring to a base during both its coiling and release. If that doesn’t happen, the result invariably is that the player swings his body rather than the club at the ball – the old story of applying oneself rather than the clubhead.

I think ‘relax’ has been one of the most damaging words in golf teaching, in that it has often been applied to the whole of the set-up, rather than to the upper areas of the body, where relaxation can promote freedom of movement. For the majority of players, however, relaxation from the hips down is one of the worst thoughts to have in mind. Freedom of movement of the feet and legs is exactly what isn’t required.

In saying this, I realize the need for care. There will be those who read into these words a necessity to root themselves to the ground like telegraph poles. What we seek, in terms of leg action, is a happy medium between rooted stiffness and uncontrolled sloppiness. Perhaps the best word to describe this feel is ‘liveliness’ – a sensation that we are planted firmly on the floor, but that from this base we can generate and control the power in the spring system overhead.

Perhaps I can put across that feeling by reiterating that, in my concept of the good golf swing, it is impossible to hold a top-of-the backswing position for more than a few seconds, because the sheer muscular strain on the legs and hips of the correct wind-up will force them to unwind after a very brief period.

It is often said that the golf swing starts on the ground, and there is no denying this (try swinging while sitting in a chair if you want proof). Unfortunately, taking the idea literally, many players tend to initiate the swing with a ground-level movement, generally either by lifting the left heel or collapsing the left knee forwards, or both. They are dead ducks from that moment on.

Foot and leg action is never an initiating movement, but is the result of the initial movements, which are the swing away of the arms and club and the turn or wind-up of the shoulders.

Thus, a feeling of ‘liveliness’ should always be sought at address. To promote this, for a full swing, your weight should be comfortably balanced between the balls and heels of each foot, but favouring the balls if anything. You should strive for firmness and a sense of balance, but also a feeling that you are ready to take off – a poised sensation similar, perhaps, to that of an athlete preparing to run or jump. Above all, your knees must be flexed and – this is an absolute fundamental – the right knee must remain flexed throughout the swing.

If you address the ball, then make the movement that would be your initial movement in sitting down, you are going a long way to establishing the correct set-up for good foot and leg action. But beware that you don’t – as so many do – stand up again on a straightened right leg as you begin to swing.

If you start your swing correctly, your left heel will not shoot up off the ground; you will not spin on your left toe as your whole body wobbles round to the right; your left knee will not cave in; your right knee will not straighten and lock. The correct start to a lively, springy wind-up will begin to affect the left foot and leg some time after the club has gone back – usually as it reaches hip height. Around that stage of the swing your left knee will be dragged, by the sheer torque of the wind-up, in towards your right leg. Your left heel may rise slightly, the amount depending on your build and suppleness. But the chief movement of your left foot will be to roll in towards the right, pulling the weight remaining on your left side on to the inside of your left foot, not onto the toe. Throughout this wind-up action, your right leg will hardly move. Above all, your right knee must not straighten.

It might be as well, while we’re on the subject of feet and legs, to say something about weight transference – a highly controversial point in golf teaching. Quite candidly, I believe that much of the talk about weight transference has done a lot of harm to a lot of golfers. As I see it, there should never be a conscious or deliberate effort to transfer weight one way or the other in the golf swing. Doing so – apart from promoting all sorts of dance-like antics – leads to a host of other faults, of which tilting and swaying the entire body are prime examples. If your upper body winds up against the springy resistance of your feet and legs, whatever weight transfer is necessary will occur naturally on your backswing.

The same applies in the downswing. If what has gone before is correct, if your downswing starts with a coordinated hip movement and arm swing, your feet and legs will do their job automatically, and transfer your weight naturally. But if your backswing is wrong, with your left leg releasing and your right leg stiffening, it is virtually impossible for your legs and hips to work correctly on the way down. Instead, your shoulders will be forced to take over in that commonest – and ugliest – of all golfing sights, the collapsing heave.

Rhythm and tempo

Jerking and rushing the club back are among the most common faults that I encounter at every level of golf, short of the very top. Their most common causes are anxiety and confusion regarding swing technique, producing an almost irresistible urge to get the action over with as fast as possible. On the physical level, the great destroyer is excessive muscular tension, particularly when it freezes the player into total immobility at address.

Understanding exactly what you are trying to do when you swing, then consciously trying to do it, conditions your mind to allow you to begin the action at a leisurely pace and with a fluidity of motion.

Remaining slightly in motion in some part of your body throughout your set-up procedure, then initiating the swing with a confidence-building ‘trigger’, guards your muscles against locking up.

Stay relaxed over the ball by gently easing your legs and shoulders and ‘hanging’ your arms loosely as you complete your set-up. Watch good players to get a feel for these tiny, but vital tension-fighters.

There are numerous ways to trigger the swing, from Sam Snead’s and Jack Nicklaus’s famous chin-swivel to Gary Player’s pronounced right knee kick-in. Most effective for most people is the forward-press, a slight targetwards inclination of the hands and hips from which the player, so to speak, ‘rebounds’ into a running start.

Again, study the triggers of good players, experiment to find the one that works best for you, then practise it until it becomes second nature.

Ladies, you can hit it farther!

With very few exceptions, women do not hit the ball as far as they could. Indeed, the long hitter among women is immediately exceptional, and will often come into national and even international prominence as a golfer almost on the strength of this ability alone. Such is not true of men’s golf, where achieving distance is much less a problem than controlling it.

It is true, of course, that women do not hit the ball as far as men because they do not have the physical equipment to generate comparable clubhead speed. What the woman player must realize, however, is that distance isn’t just clubhead speed – it is clubhead speed accurately applied. While maybe limited to the extent she can increase her actual clubhead speed, there is usually a great deal she can do to deliver what she possesses more effectively to the ball. It is, in fact, incorrect application of the club – not lack of strength – that makes so many ladies play what I describe as pat-ball golf.

The same clubhead speed that many women golfers apply down and across the ball, with the clubface open, would hit it a heck of a lot farther if it were applied with the clubhead travelling virtually parallel to the ground and along the target line with the face square.

Where distance is concerned, it is paramount for the club to approach the ball from directly behind, as opposed to from above and behind. To swing the clubhead into the very back of the ball on a shallow arc in the impact zone, a woman must use her arms, wrists and hands earlier in the downswing than does a man. For most women golfers, this means a conscious, deliberate effort to get their arms really going from the top of the backswing. There are two reasons for this: (i) it takes longer for a woman to reach her maximum clubhead speed; and (ii) the clubhead is more likely to approach the ball from directly behind, rather than from above, and thus achieve flush contact.

Effects of ‘hitting earlier’ are very noticeable in the swings of top woman golfers, and any player anxious to improve would do well to study them. She will see that a great many good women players come up on their toes during the downswing and remain there until well after impact. The reason for it, of course, is to allow the clubhead to swing squarely into the ball on the shallow-bottomed arc engendered by an earlier hit, without it touching the ground behind the ball.

Another result of hitting earlier among ladies is an absence of ‘dinner-plate’ divots with the irons. Few women have the muscular strength to hit down and through on a steep arc with an iron. Hitting earlier brings the clubhead into the ball on a flatter trajectory, with less divot – but produces just as effective a shot, so long as the ball isn’t ‘scooped.’

How does a woman golfer hit ‘earlier’?

First, she determines that, for ever more, she will not be content to play pat-ball, but will really try to swish the club through the ball as fast as possible. This is the mental hurdle that most women club golfers (and a few of better standard) must first surmount if they are going to improve substantially.

On the physical side, the first major factor for attention is usually the grip. Most women tend to cut the ball and, if this is the case, they must not be frightened of adopting a powerful grip. The left hand particularly should be placed well on top of the shaft, with up to three knuckles showing and the thumb well to the right side of the grip. The shaft should be held firmly in both the palm and the fingers, and there should be a feeling that the club is nestling deep into the hand so that the fingers can really hold on to it (if this isn’t possible the grips are too thick). The right hand may need to be a little under the shaft, the ‘V’ of the thumb and forefinger pointing between the right ear and right shoulder, with the club held snug in the fingers, and the forefinger ‘triggered’ around the shaft.

The grip should feel firm, yet leave the arms flexible, not tense or rigid. If this is difficult with the overlapping grip, try an interlocking or double-handed grip (ensuring, of course, that your hands are as close together as possible). Some experiment may be necessary, especially if you have tended to hold the club ‘weakly’ – left hand well to the left and right hand on top. Don’t be frightened to make it.

A woman who cuts the ball should never stand to her shots in an ‘open’ position – with feet, hips and shoulders aimed to the left of the target. A slightly closed shoulder alignment will not only help her to swing the club solidly into the back of the ball, but will encourage an inside-out angle of attack that will produce a touch of distance-generating ‘draw’.

A wide arc in the backswing is even more essential to women golfers than it is to men, simply to make room for the bigger arc on the way down that is imperative if they are to get the clubhead really motoring. Indeed, most women sense this need for a wide backswing, but unfortunately their efforts to achieve it often lead to a loss of control, through excessive body movement or a tendency to sway.

Women find it difficult to coil their bodies; to ‘wind the spring’ that puts power into a golf shot. In an effort to get the necessary width of arc, they release from the ground, turn their whole torso from the feet, as the initial backswing movement. Women as well as men must learn to keep the head reasonably still to ‘anchor’ the swing; and to turn the upper body from the hips up, while the feet and legs resist.

I am often taken to task for advising players, men and women, to hit earlier with the clubhead, but it is a fact that only when the swing lacks a correct wind-up does early use of the clubhead lead to trouble. Without lower-body resistance, an early hit means a feeble pass at the ball with only the hands and arms. When the swing is correctly anchored and there is a good wind-up of the upper body, a strong swing down of the arms and clubhead is essential to keep pace with the reflex release and uncoiling of the legs and hips.

Two different games!

Today, in the year 2005, men and women professionals hit the ball further than when much of the content in this book was first written. The reasons being:

i) equipment, the superior nature of today’s clubs and balls;

ii) physique, the best players are athletes today;

iii) most important, there are now so many good swingers whose impact is so pure and correct; that’s why the ball goes a long way. As I have stressed many times over the years, distance is clubhead speed correctly applied.

Therefore the gap has widened between handicap players and tournament players. This was just as I predicted the game would develop in the conclusion of my book Impact on Golf with Laddie Lucas in the mid-1980s. I envisaged that golf would become almost two different games – in the sense of being totally disparate between the professional and amateur.

When one looks at the facts, this indisputably is now the case. Handicaps of the average player have not come down in the last twenty years. Nor has the overall quality of play improved, despite improvements in club and ball technology. Yet the professional game has come on leaps and bounds, with a greater proportion of the field hitting the ball better, farther, and more consistently. Indeed, I would go as far to say that in the pro game the gap between the best and the rest is narrower than at any time in the history of the game. In all honesty, I do not see that trend being reversed.