Some tournament professionals use a wedge for all the little shots around the green and play them very well. But I cannot stress too strongly that this is not the way for 99 percent of golfers, including Tour players, to play those little chips and pitch shots which are such valuable stroke savers.

The routine should be first to examine the lie of the ball, then to look at the flagstick, then to visualize the ball landing on the green and rolling up to the hole, and finally to select the club most suitable to turn that image into reality.

Visualize … then commit

On any pitch or chip you must have a mental picture of the shot you are attempting, before you can even choose the right club for it. I hear far too many players saying things like: ‘I always chip with my 7-iron.’ When I hear this, I know they don’t picture the flight and run of the shot before they play it.

Many factors, of course, affect what picture one may get of a particular shot: the speed of the green, slopes on the green, wind, conditions of the approach to the green, etc, etc. Once you have worked out the shot, select the club that will do the work most simply; then – let it! If you need a low shot to run, you will obviously select a straight-faced club; and when you need height and stop, a more lofted one.

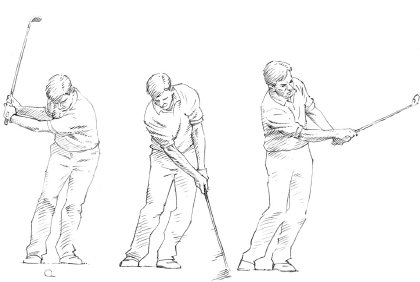

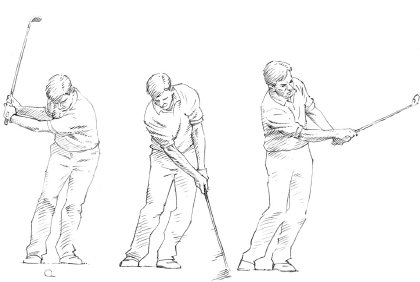

Once you have the right club it is only a question of hitting through the ball, letting the loft of the club you have chosen give the height and run necessary for the shot. The hands should be slightly ahead of the ball at address and impact, so that the bottom of the arc will come just after the ball is struck, thus avoiding any scooping action, with its dangers of a ‘fluff’ or a ‘top’.

These two foozles are often caused by choosing too-straight-faced a club for the shot you want. The player senses that the shot is going to run too much and tries to add height and stop to it by flicking the wrists early in the downswing.

Summing up: first select the right club; then let it do the work. And always commit yourself to a specific line and a spot where you want to land the ball. Commitment is so important in the short game. Doubt is your No.1 enemy.

Cause and effect in chipping and pitching

The chip shot is used around the green when there are no hazards between your ball and the hole. The object is to drop the ball on the edge of the putting surface and let it run the rest of the way to the hole. Club selection is largely governed by the distance the ball must carry through the air before reaching the green, and the amount of green between you and the hole. For example, from a few feet off the putting surface a 5-iron might loft the ball to the edge of the green, from where it would roll to the hole. But from 15 yards out, your ball would roll too far. Thus you’d probably need an 8-iron or an even more lofted club.

The pitch shot is the exact opposite of the chip. You use a 9-iron, pitching-wedge or sand-wedge to hit the ball high through the air so that it lands and stops as quickly as possible. It is the shot to play over hazards, or when the green is wet and holding, or for some reason the amount of roll is difficult to judge.

The major difference between the two shots is that you are trying to minimize backspin with a chip shot and to maximize it with a pitch shot. Under normal conditions the chip shot is the safer of the two, because roll is easier to judge than flight, and easier to control. Also, most golfers find it easier on short shots to make solid contact with a less-lofted club, the extreme example being, of course, a putter.

The first step in getting ready to play either a chip or pitch is the same as for any other golf shot. You aim the clubface correctly, take your proper grip on the club, then place your feet in relation to the clubface. On both chip and pitch shots, it helps to have your weight predominantly on the left leg, and to set your hands ahead of the clubface. Your legs should be comfortably flexed and your body fairly relaxed (but never crouched over the ball). Place your feet fairly close together in a slightly open stance, but keep your shoulders parallel to the target line.

Neither a chip shot nor a short pitch shot requires conscious body action. All you need is a smooth back-and-through swing with your arms, hands and club – an unrushed, even-paced movement, in which the clubface never passes the hands until the ball has been sent on its way.

In both pitching and chipping, the length of shot is determined largely by the length of your backswing. Too short a backswing will lead you to stab quickly at the ball, but swing the club too far back and you’ll tend to slow down before impact. In your mental picture of the shot you will have selected a spot on the green where you want the ball to land. Take a few practice swings until you find a length that you sense will hit the ball to this spot. A few minutes’ practice will tell you how far the ball travels through the air for various lengths of backswing.

Because the chip is played when there are no obstacles between you and the hole, the height and flight of the shot is dictated by the loft of the club you select. Thus you need little or no wrist action when chipping. You play pitch shots, however, in a wide variety of situations that call for different degrees of height and distance. For example, if the ball has to be pitched over a bunker with the pin set close to the edge of the green on the near side, a soft lob shot would be required. This involves positioning the ball well forward at address, opening the clubface, and keeping your hands level with the ball at address and impact. On the other hand, if you were playing a longish pitch shot into the wind, you would need to move the ball back at address, hooding the clubface slightly by keeping your hands well in front of the ball at address and impact.

A steep, downward hit is necessary to pitch effectively, and that requires more wrist action than in the chip shot stroke. The set-up is very much as for the chip – feet close together, stance slightly open, weight on the left side, and hands ahead of the clubface. But that is as far as the similarity goes. In the pitch-shot backswing, the wrists should cock easily and remain cocked throughout the downswing – your left hand must ‘lead’ the clubface through impact.

Beware of trying to scoop the ball into the air by leaning back on the right foot and hitting upwards with the clubhead. Set your weight on your left foot, keep it there, and hit down into the ball – the loft of the club will get it airborne rapidly.

Many golfers seem to have the erroneous idea that pitching well involves ‘cutting the ball up’ – swinging into the ball from outside the target line and holding or ‘blocking’ the face of the club open at impact. This is certainly a useful shot in certain circumstances, as when the ball must fly high and stop virtually in its own pitch mark, but it is not an easy shot to play and requires considerable confidence.

Too many people try to play every pitch shot this way, and thus turn a relatively simple shot into a difficult one. Watch any of the world’s great wedge players and you will see that they most frequently ‘draw’ the ball into the pin – moving it slightly from right to left – and yet still make it spin back off the second bounce. They achieve their stopping power much more through backspin – created by a sharp, accurate, downward hit – than by a high trajectory.

The technique for the chip shot is very close to that for the pitch, with one vital difference; whereas the pitch shot requires a free cocking of the wrists in the backswing, the chip shot requires more of an arm swing – although the wrists should never be rigid. Assuming you have a good lie, the chip shot is a firm, controlled sweep with the arms and club working as a unit, with just a little ‘give’ in the wrists and hips to prevent the action from being jerky or wooden.

One point I would stress again to sum up concerns the path of the swing. Although the club swings straight back from the ball initially, it soon must move inside the target line if we are going to be able to swing it straight through the ball at impact. Since the followthrough is often curtailed on short shots, ‘inside to straight-through’ is a good mental picture for the club’s path on chip and pitch shots. If you are a confessed bad short-game player, I am sure that ‘seeing’ the stroke this way will help you.

The Lob Wedge

There has recently been a vogue for carrying three wedges: pitching wedge, sand wedge and lob wedge of 60-degrees or more loft. I think this is an excellent idea and have done so for 50 years or so. The reason I discarded the 2-iron in favour of a third wedge was that I could play the ball back in my stance and hit a 2-iron shot with a 3-iron, so it was easy enough to create a vacancy in my bag.

I have always been a believer in a close graduation of distances in the shorter clubs because it is more difficult to play half and three-quarter shots close to the green. So it is always better to a play a full shot into the green; hence the value of having a larger range of clubs to accommodate smaller graduations in distance.

Be competitive when you practise

Nobody has ever mastered the game of golf, or come remotely close to perfection. It is possible to imagine that a great champion will arise who splits every fairway with booming drives and hits his irons with uncanny precision. Some golfers have briefly come so close to that level of control that they could, in the words of Tom Watson, smell total mastery in those areas of the game.

But the greatest of players always have, and always will have, plenty of scope for improvement in the critical departments of pitching, chipping, and putting. These are the skills that offer the best opportunities for saving strokes. Oddly enough, they are commonly the neglected part of a golfer’s game when it comes to practice. Well, it is not so odd perhaps, since practising these little touch shots does not give the golfer that tingle of sensuous satisfaction at hitting a full shot flush off the sweet spot. Chipping and putting practice soon gets boring. And if you are bored you do not concentrate properly, so the practice does not do you any good.

The answer is to make it competitive. Then it’s fun. Then it does you good. When I do team coaching the players are subjected to a tough regime of serious practice followed by a round on the course. But I think they get the most value, and certainly the most enjoyment, from our evening contests.

Each day I mark out tee areas around the practice green for specific holes. The players put their entry money into a hat and play winner-takes-all. The rules are simple. One penalty stroke if your chip does not pitch on to the putting surface. And one club and a putter only. I nominate which club must be used. Each day I choose a different club.

With every team, of every nationality, this is the most popular element of the coaching week. I am convinced that it does them the most good. And as a valuable bonus, the fierce but friendly competition fosters a wonderful team spirit among players who may have arrived as strangers.

A simple tip for chipping

In order to make the ball travel upwards, you have to swing the club downwards. A good swing thought is to try to finish with the clubhead low to the ground when you play a regular chip shot. This encourages the correct, slightly descending angle of attack and keeps your hands ahead of the clubhead – a combination that helps eliminate the danger of you scooping at the ball.

Here’s a useful pitching drill. Place a second ball roughly eight inches behind the object ball. To avoid contact with that second ball, the clubhead must travel into impact on a descending angle of attack. If you combine that with a slightly open clubface and keep the body moving, thus avoiding independent hand and wrist action, you’ll learn to hit wonderful soft-landing pitch shots.

Texas Wedge

Don’t be frightened to take a putter from off the green, if circumstances make a lofted shot more difficult. Obviously, if the grass is thick on the fairway or apron, or the ground is broken or muddy, the percentages are with a slightly lofted shot. If the ground is clean and smooth, by all means use a putter. Tournament pros know that a bad putt will almost always finish better than a bad chip, under these conditions. So should you.

Soft hands give your chipping more feel

Nick Faldo has often been accused of being mechanical, but I don’t agree. Certainly not when you look at the way he plays little chip shots and pitches, where I think there’s great fluidity and softness to his technique.

That’s because although Nick is a very strong, muscular individual, he has wonderful touch. For a start he has a great looking grip, which he applies to the club with just the right amount of pressure. It’s a soft, but secure hold. And although I know Nick then likes to feel that the trunk of his body controls the motion of his swing, his hands and arms stay so soft that the club flows back and forth ever so smoothly and very correctly. It looks, feels, and is, extremely controlled.

When you practice your chipping, try to adopt a posture whereby the hands and arms hang free from tension and keep your grip nice and soft. Then, as you swing the club back with your arms and shoulders, feel a little bit of ‘give’ in your wrists as the club changes direction from backswing to downswing. That ‘lag’ effect is exactly what you want, and is created by the shoulders unwinding through the ball. It establishes the correct angles in your wrists and helps to make sure your hands lead the club into impact – striking it sweetly but still with a sense of authority.

No sloppiness, no mishits, just perfect ball-turf contact. And the great thing is, you can apply that technique to any club from a 6-iron to a sand wedge to produce a whole range of shots around the green.

Gary Player has always been a great, great bunker player. At the peak of his career, he was in a class by himself. One of the reasons he became so good from sand was the way he practised. He used to throw a handful of balls into a bunker and then play each one as it lay. So often we lesser mortals place balls in the sand on a perfect lie and show off our skills, but when faced with something a little unusual we’re suddenly not so good. When Gary practised it didn’t matter if the ball was buried, lying perfectly, or on some sort of slope, he’d just deal with it. That gave him the physical skills and, just as importantly, the wonderful imagination that often separates the great from the good.

This was the philosophy he applied to practising every department of his game. He’d spend as much time being creative as he would being conventional. I remember when we were both playing in a tournament at Crans sur Sierre in Switzerland, each night before it got dark we used to go to the course with just a putter and a wedge and take it in turns nominating shots – the idea being to get up-and-down in a pitch and a putt. We would start out with fairly orthodox shots, then become increasingly creative as our skill and imagination cried out for greater challenges.

My advice to you is practise like Gary Player used to. If you’re working on your bunker play, don’t set yourself up with a perfect lie every time. Chuck in a dozen or so balls and play each one as it lies. Bear in mind that the standard greenside splash bunker shot requires a combination of an open clubface and an out-to-in swing path, taking a portion of sand from under the ball without hitting the actual ball.

Learn how to adapt that technique to suit different situations. In a fried-egg lie you need to take more sand and generate more force, but still play with an open clubface. If the ball is completely plugged, you need a steep angle of attack and a square clubface. On any kind of slope you need to alter your weight distribution at address to vary the angle of attack – favouring the back foot on an upslope, and the front foot on a downslope. By giving yourself these shots to play, you soon learn how to deal with them.

And feel free to carry this varied approach right through your entire game. Ideally, get together with a friend and call different shots, just as Gary and I did. If you’re on your own, call the shots yourself. This kind of practice fuels your imagination and develops your technique – together that helps take your game on to a new level.

Chip with arms, but add wrists to pitch

In chipping you need minimum height and maximum roll, so you should swing the club predominantly with your arms. Sweep the ball forward with little wrist action. In pitching, you need plenty of height but no roll, so you should use more wrist action to make the ball rise. But in both shots, the clubface must never catch up with the hands until after impact.

In both pitching and chipping, the length of the shot is determined largely by the length of your backswing. Too short a backswing will lead you to stab quickly at the ball, but swing the club too far and you’ll tend to slow down before impact.

In your mental picture of the shot you will have selected a spot on the green where you want the ball to land. Take a few practice swings until you find the length that you sense will hit the ball to this spot. A few minutes’ practice will tell you how far the ball travels through the air for various length backswings.

Stand open … but not across

Your body does not need to coil and uncoil for a chip or short pitch shot – you swing the club primarily with your hands and arms. But you do need room to swing your arms past your body, and opening your stance – pulling your left foot back a little – helps you clear your left side.

The danger is that you may also set your shoulders ‘open’ to the target line by instinctively matching your alignment to your stance. When this happens, in trying to swing the club straight back along your target line you will actually have to pull it ‘inside’ relative to your shoulder alignment. More often than not the result will be a ‘rebound’ that throws the club outside the target line on the throughswing. This is the chief cause of the most common short game fault – pulling the ball left.

Find the perfect swing length

A successful pitching method relies on you generating a length of swing and degree of body turn that enables you to accelerate into the ball with authority, whatever distance pitch shot you are hitting.

To that end, try this exercise. Go out on to the range with just your wedge and a dozen or so balls. Give yourself a comfortable distance, say 70 yards, and hit the first couple of shots with a distinctly longer swing than you would usually make. Follow that up with a couple of shots using what feels like a much shorter swing than normal. Repeat the process a couple of times.

What you are looking for is a length of swing that isn’t so short that you struggle to generate sufficient speed, but neither is it so long that you are afraid to hit the ball. The ideal length swing should enable you to swing down with natural acceleration, producing what feels like solid ball-turf contact and the ideal distance for the shot you are hitting.

The good pitcher finds a length of swing that promotes natural acceleration through impact.

How to play the basic bunker shot

It is sometimes said that splashing the ball from sand is the easiest shot in the game. I don’t go all the way with that idea, but I would agree that given a basic understanding of the problems and methods of getting the ball out of sand, the average player can at least overcome the fear that seems to paralyse him every time his ball lands in a bunker. And that alone will give him a 50 percent chance of getting out of the sand with only one blow struck.

The basic splash shot is a relatively easy shot to play, once you’ve established confidence. If there is a secret to playing the splash shot, it lies in knowing how far behind the ball to apply the clubhead and then having the confidence to do it. In this shot the ball itself is never contacted by the clubface. The sand is struck behind the ball and the sand wedge, due to its heavy protruding flange, splashes or skids through the sand beneath the ball, which flies up out of the bunker literally on a cushion of sand.

How far behind the ball should you hit the sand? The exact distance depends on the flight required and the condition of the sand, and you can only learn to judge these two factors through practice and experience. But the distance will vary between two and four inches, the less sand generally being taken, the farther the ball must travel.

As in every golf shot, the correct set-up is vital. Position the ball opposite the left heel and make sure that both your feet and shoulders are set open – your left side pulled back from the target line. Open the face of the club, fractionally for a normal trajectory, wide for a higher shot. Then swing the club smoothly along your shoulder line, i.e., out to in. I repeat, smoothly along your shoulder line. Make a full, free swing with the hands and arms. There need be no deliberate turn of the shoulders, but your knees should be flexed and your upper body relaxed.

In order to hit under and through the ball, you must be sure to get your hips moving and turning to the left as the clubhead swings down and through. Only by moving the hips can the face of the club be kept open, so that it slides through the sand under the ball. If your hips are static, the downswing becomes a movement of the hands and arms only. Then, as the clubhead approaches the ball, the arms start to move around the body and the clubface closes and digs into the sand. Don’t swing at the ball – think of skimming the clubface through the sand under the ball and floating it out. The shot is a gentle splash, not a thunderous blast.

In bunkers, control distance by your set-up

You can govern the distance you ‘splash’ the ball from sand by a very simple graduation of your set-up geometry. For a very short shot, aim your shoulders well left of the pin and your clubface well to the right of the pin. For a little more distance, narrow the angle between your shoulders and the clubface. For a longer shot yet, narrow the angle even more. It is absolutely vital, of course, that you swing the club up and down along your shoulder line – not along your target line.

Vary your set-up geometry to control ball flight, progressively more open the closer you are to the flag.

Knife down and under a buried ball

Any time your ball is buried in the sand, the only sure way to get it out is to swing the clubhead well down and under the ball. The easiest way to do that is close the clubface so that its sharp leading edge will ‘knife’ through the sand when you swing sharply down behind the ball.

‘Crisis management’

If you suffer from a total lack of confidence with bunker shots, I recommend you practise in sand without a ball. Open the clubface at address and make long, smoothly accelerating swings. Get used to the sensation of the clubhead sliding through the sand, not digging into it. If you can repeat that action when there’s a ball lying there, the clubhead design of the sand-wedge will do the rest for you. You’ll never fear bunker shots again.