‘See’ the line and ‘strike’ the ball

Putting is not golf: it is a game within golf. How good you are at hitting the ball through the air bears little relation to how well you can roll it along the ground. Putting is largely a matter of instinct, touch, and nerve. Thus if you are naturally a good putter, nothing – and I mean nothing – should persuade you to change your method or your approach to this part of the game. If you can get the ball in the hole when it matters, how you do so is of no consequence.

Unfortunately, the better a golfer becomes at the through-the-air game, the more important his putting becomes. If you hit a green 500 yards away in four strokes and get down in one putt, you are pleased. If you hit it in two strokes then take three more to hole out, you are incensed. Most golfers never totally evade putting problems. The following is for this unfortunate majority.

It seems to me that golfers who putt poorly, especially if they miss the short ones, do so above all else because they lack authority of stroke. Nervousness, pressure, lack of confidence, lack of concentration, the general tizz that this game can wrap us in, leads to indecisiveness about line and distance; and, worse still, about striking the ball. We tend to wave at it, coax it, steer it, drag it, jab it, twitch it – anything but hit it.

Consequently, the poor putter needs, first, a mental resolution, a determination to strike the ball with the putter-head; and second, a method that encourages him to do so. The first is a question of total mental committal to a particular line. Sometimes we can ‘see’ the line better than at other times. But, whatever you do, you must commit yourself totally to strike the ball in a certain direction.

The shortest route to an authoritative strike, I believe, is to hit the ball against the left wrist, never past it. On short putts the left wrist never quits nor bends at any stage of the forward stroke. Some golfers may interpret this as a stiff-wristed action. It isn’t. There is a wrist break going back, but none going forward, so that the clubface never gets ahead of the hands until well after impact.

As we get farther away from the hole, there is a ‘softening’ in this kind of action, of course. The strike becomes more of stroke, the arms swing farther and more freely on the backswing, and the hands at some stage pass the left wrist on the followthrough. But the principles remain the same.

Swing putter back inside line to stroke ball on line

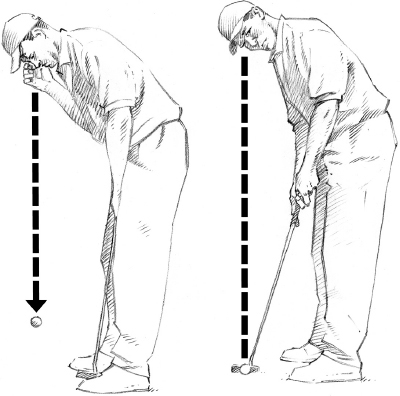

You’ve probably heard or read that you should ‘take the putter straight back from the ball’ and ‘keep the blade close to the ground’. Short of using a very contrived stroke – and risking a body sway – these two pieces of advice are incompatible.

If you swing the putter straight back along an extension of your target line, it will naturally tend to raise well above the ground. You can only keep the blade close to the ground by swinging it back ‘inside’ your target line, on all but very short putts.

If you do literally force the putter straight back, it will frequently rise so high that you risk chopping down on the ball, rather than stroking it solidly forward; and you will also tend to pull the ball left by returning the putter-head to it across the target line from out to in. The fact is that, to swing ‘straight through’ the ball, you must allow the putter-head to move naturally ‘inside’ the target line on the backswing.

NB. The use of the long, or broomhandle, putter has changed things somewhat in terms of the path of the stroke. Because the shaft is more vertical at address, the putter-head tracks a straighter path back and forth. It is, in essence, more pendulum-like. Of course, these putters might not be in use forever!

Never up, never win

How often have you had the experience of everything resting on the last putt of the match and watching your partner belt the ball so hard that the ball races past, or even clear over the top of the hole? He then turns with a soppy expression of contrition on his face and tries to excuse his imbecility by saying: ‘well, I had to give it a chance’.

That is exactly what he did not do. The ball had no chance of dropping at that speed. The hoary old expression ‘never up, never in’ is frequently trotted out on these occasions, adding banality to injury.

Some, like Gary Player, have the courage to rap short putts so firmly that they can be hit straight into the hole, ignoring any breaks. Most of the great putters, including Bobby Jones and Bobby Locke, played their putts with just enough speed to die the ball into the hole. This policy makes the hole much wider on short putts.

On long putts, most good players concentrate on distance above all and try to get the exact speed to carry the ball up to the hole and no farther. If the ball should drop then that is a bonus, but it is not the original intention. The control of speed, or weight, is the vital factor in judging the amount of break the ball will take. On the longer putts distance is more important than direction.

A quick way to develop authority of strike

Take too long a backswing and you may unconsciously decelerate the putter-head prior to impact. This is one of the commonest causes of feeble putting. I increase my own authority of striking very quickly, if I practise putting on the carpet at home with a book placed so that it severely limits my backswing.

Putting’s correct impact factors

There have been lots of better players than Ben Crenshaw in the last century, but there really hasn’t been a better putter. He has a very distinctive stroke. He stands very tall, his arms relatively straight, and from there he pivots his body. His arms and the putter move directly in harmony with that pivot. There are no abrupt movements, the putter changes direction very smoothly and accelerates gradually as it strikes the ball. It’s all very much one-piece, with no independent hand and wrist action.

Ben himself has said: ‘I try to build my putts around pace’ and an inside-to-square method, which he adopts, is great for achieving this because it encourages the putter to swing freely. The essence of Ben’s success, though, is that he manages to get the putter swinging through the ball along the correct line, with the putter-face square to that line, travelling at the right speed for the distance the ball needs to roll to the hole. These are the impact factors of a great putter at work.

The key message is that you don’t necessarily have to putt like Ben Crenshaw, but you do need to be conscious of those all-important impact factors and go about fulfilling them in a way that feels most natural to you personally. I don’t believe in suddenly changing your method because you see someone on television ‘putting the lights out’. Be yourself when it comes to putting.

Hit ’em quick

I would hesitate to recommend Colin Montgomerie’s method of putting to anyone who doesn’t already find it a very natural way of putting. However, getting away from the technical side for a moment, one of the things I really do like about his putting stroke is the no-nonsense way he gets on with it. Once he’s over the ball and is committed to the line, it’s ‘one look, bang’. No hanging about. I think that’s a good way to putt, mainly because the longer you stand over a putt the more chance you have to tense up or talk yourself out of holing it.

Next time you have a spare few minutes, go on to the practice putting green and give Colin’s ‘one look and hit’ method a try. Make up your mind on the line before you are over the ball – and I mean really commit yourself 100 percent to that line. Then once you’re over the ball, see the line and hit the ball along it. Strike a good putt and leave the rest in the lap of the Gods. You can do no more than that.

One final thing. Under no circumstances should you ever deviate from that routine. Many times I see people take twice as long over a crucial putt, which usually means they don’t hole it. Look back to the penultimate hole of the 1997 US Open, when the gallery distracted Colin as he was about to putt. Now that wasn’t Colin’s fault, but it knocked him out of his usual routine, and in my view that’s why he missed the putt. And it virtually cost him the championship. So try to stick to your routine at all costs. You’ll putt better for it, I promise you.

If you cannot see a definite break on a putt, you must commit 100 percent to straight. Decisiveness is the best policy.

Groove perfect putting rhythm, like Arnie

Arnold Palmer was the boldest putter I’ve ever seen. He charged his putts at the hole, without a second thought for the one coming back. He was just so confident. There was a real sense of acceleration through the ball. It’s one of the reasons Arnold holed so many putts in his career – the ball was struck so firmly that it fought to hold its line all the way to the hole.

Arnold’s putting stroke wasn’t only positive, it was also perfectly timed. There was a wonderful rhythm to it. People talk about rhythm in the full swing, but it’s just as important with the putter. The putter should flow back and forth, smoothly but with good rhythm and acceleration through the ball.

Good rhythm in your putting stroke stems from the correct length backswing. If the backswing is too short, you have to really hit at the ball to create sufficient speed for that putt. If your backswing is too long, you have to decelerate to avoid hitting the ball too hard. Work at developing a length of backswing that enables you to swing the putter into the back of the ball with natural acceleration. Your stroke should feel positive and purposeful, but at the same time very rhythmical.

As you make practice putting strokes, try to feel the length of swing that will send the ball the required distance. Then repeat that stroke and let the ball get in the way of the swinging putter-head. If your stroke is smooth and rhythmical, I promise you will be surprised how quickly your judgement of pace improves.

NB. Arnold had a very wristy stroke, which worked wonderfully on the relatively slow greens that were typical in his heyday. Today, wristy strokes are less popular and that is purely down to circumstance. Greens are so much faster these days that a less wristy, more arms-and-shoulders-dominated stroke is more effective and consistent.

Find a pace that suits you … and stick to it

Think about what sort of putter you are. Do you feel more comfortable lagging your putts or do you prefer to charge them at the hole? If you have a preference, commit yourself to sticking with that at all times, whatever the circumstances. Don’t be influenced to putt another way. That can be disastrous.

In-to-straight

If the putter-shaft were fitted absolutely at right angles to the clubhead we could take the club straight back and straight through with a perfect pendulum stroke. But the rules say that the shaft has to be set at an angle and we must accommodate that angle by taking the clubhead back slightly on an inside arc. The return swing is from in-to-straight through the ball.

NB. I would refer you once again to the comments on the broomhandle putter, earlier in this section.

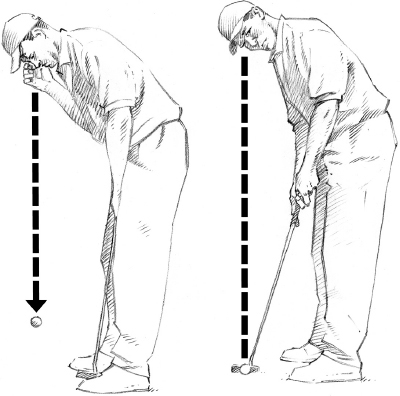

You can’t hit what you can’t see

Tiger Woods holes so many crucial putts it’s incredible. Mechanically, I can’t fault his stroke, so let’s focus on something positive that might help you hole more putts. One of the things I know he used to work on with his then coach Butch Harmon is the position of his head, specifically making sure that his eye-line is parallel to the target line at address. Also the way he looks at the hole, swivelling his head rather than lifting it, to see the line. Perhaps you’ve not considered that, but I tell you it can make a mighty difference to the number of putts that start on the correct line.

Also, next time you practise your putting adopt your normal address position and make sure your eyes are over the ball by dropping a second ball from the bridge of your nose. Address the ball on the spot where it lands.

Make sure your eyes are over the ball, and that you swivel, rather than lift, your head to look at the hole.

Set hands parallel to putter-face

There are no ‘musts’ about grip and set-up for putting – if whatever you do now works consistently, stick with it. But if you are an indifferent putter, try setting your hands on the putter so that they are parallel to its face, and positioning your eyes over or slightly behind the ball. These are two factors common to most of the better putters among tournament professionals.

‘Hit and hark’ on your putts

The head is important. It must be kept really still if the ball is to be struck firmly and accurately. Set your head in one spot and hold it there as long as you can. Try to ‘hit and hark’. Strike the ball and wait to hear it drop in the hole before you look up.

The final countdown

One final thought. Always try to spend at least five minutes putting before an important round – and practise the middle and long-distance putts. This is the best way to induce rhythm and feel. If you practise short putts without being under pressure to hole them, you are apt to miss a few simply because they aren’t important, which does nothing for your confidence.

Take the break out of short putts … if you have the nerve!

At his peak, Tom Watson was one of the greatest holerouters I’ve ever seen. It wasn’t just the fact that he seemed to hole every putt he looked at. It was the way he holed them. Bang! Straight in the back of the hole. You’d swear he was trying to dent the back of the cup.

Tom’s entire short game was brisk and positive, so there’s no doubt in my mind that banging in the short putts was very much his style. It was also a reflection on the amazing confidence of the man. As he said himself once: ‘I was amazing. I aimed the putter and I knew the ball was going right along that line.’

The advantage of this style of putting is that it eliminates break on all but the most severe slopes. You hardly ever have to start the ball outside the hole. I think to a degree if you eliminate break on a putt, you eliminate doubt. If you give Tom’s method a try, make sure it’s not on the first green of the monthly medal, but on the practice green so that you get accustomed to striking the ball more firmly from such short range.

What putter to use?

The choice of putter is highly individual. A mallet is often thought to be best for slow, wet greens; a blade for smooth, fast greens. Probably the best answer is to use the putter that gives you the best feel, or the one in which you have the most confidence. But don’t stick with it if your putting goes off. I’m a great believer in changing putters if I’m putting badly. However, if you follow this advice and have more than one putter, make them as different as possible from each other. A blade and a mallet are good alternatives.