In reading this chapter, I’d say wherever necessary please refer back to the passage earlier in the book where we discussed the relevance of golf’s impact factors, namely: clubface path, aim, and angle of approach. It will help you understand more clearly the shot-making nature of this section on Trouble Shooting.

Assessing the risks

Every golfer lands in trouble. How well he gets out depends on his mental equilibrium, his common sense, and often, in the long run, his sheer physical strength.

The first rule of playing from trouble is simply to get out. This is where mental equilibrium is so big a factor. Many golfers become so angry or dismayed when a bad miss lands them in trouble that all reason departs. They call upon temper or belief in miracles to make amends. Neither are reliable factors in golf.

The first thing to do if you are in trouble is keep calm. The second is to decide what is definitely possible in the way of recovery, what is just probable, and what is impossible. If the situation is impossible, take an unplayable lie penalty and drop away or go back and play another ball. If it is just probable, and the state of the match or the game suggests a gamble, have a go. Most of the time, stick to what is definitely possible – even if it means, as it often does, the shortest route back to the fairway.

The deeper the trouble – grass, bushes, gorse, heather, bramble, bracken, etc – the more difficult it is to get out. In all those instances, whatever the ball lies in will wrap around the club’s neck before the ball is contacted, slowing the club down, stopping it completely, or twisting the face off-line to the left.

Sheer physical strength is probably the only reliable method of shifting a ball from a really bad spot. If you lack it, play safe.

Executing various recovery shots

Most of the time, trouble means rough grass of varying depth and texture bordering the fairways. The problem here is how cleanly the clubface can be applied to the back of the ball, and how the ball will behave when grass comes between it and the clubface at impact.

Backspin is what controls a golf ball – makes it fly in a certain trajectory and stop in a certain manner – and backspin is best applied by the clubface hitting the ball a clean, slightly descending blow. Anything coming between the ball and the clubface at impact reduces backspin, thereby reducing your control over the shot.

The normal effect of grass coming between clubface and ball, because of the reduced backspin, is to make the ball fly lower and run farther when it lands.

A ball lying reasonably well in dry, light grass or semirough may be played normally, taking into account only the foregoing, i.e., that less club might be needed than when the same length or type of shot is played from the fairway.

If the ball is nestling down in long or lush grass, leaving no clear path for the clubhead to meet the back of it, the only way to remove it effectively is by a steep, descending blow with a lofted club. This shot should be played with the clubface opened a few degrees at address. Swing the club up with an early wrist-cock to produce a steep arc. In the downswing see that your hands lead the clubhead, and that your grip remains firm. The ball needs almost to be ‘punched’ out – struck a firm, descending blow. Don’t worry about followthrough. Look at the back of the ball and try to get the clubface down on to it as cleanly as possible.

Although it doesn’t always appear so, one of the most difficult trouble shots is that presented when a ball tees itself up in light rough – anything from half an inch, to two inches, above the ground. The great danger here lies in swinging the clubface underneath the ball, ballooning it weakly high into the air. Here, the only real safeguard is to watch the ball carefully and use a deep-faced club (the driver is ideal if distance is required).

Another poser is the ball under an obstacle such as the branches of a tree. Take a long iron, deloft it even more by playing the ball opposite your right toe, hood the clubface, and punch down into the ball, making sure that your hands lead at impact. Allow for a great deal of run.

An experienced and thoughtful golfer is always ready to make up shots to extricate himself from trouble. So long as you do not scoop or scrape at the ball, almost any sort of blow is permissible, and all kinds can be contrived to escape trouble.

A ball lying very close to a wall or a tree can be bounced off the obstacle to get it clear – but be careful it does not strike you or the club on the rebound. A ball in a bush can often be bunted out backwards between the legs by chopping down on it vertically. Reversed so that the toe points down, a right-handed club can be used to knock out a ball from a spot where only a left-handed swing will do.

You can get a lot of distance out of grass if height is not necessary by using an inelegant shot with a medium iron. Set up with the ball well back towards your right foot and weight predominantly on the left side. Hood the clubface slightly and, again, pick up the club quickly in the backswing to keep it out of the grass, then literally smash it down into the back of the ball with your hands and arms. This action will not produce a good looking golf shot, but it will get the ball moving on a low trajectory that will send it running a long way. Allow for the ball to hook.

One of the most difficult shots in golf is a short pitch from thick, lush grass – especially when there is little margin for error as often happens when a bunker intervenes between you and the pin, and the ball must fly the necessary distance but still land softly. The grooming of many American courses makes this a common problem for the US tournament professionals, and some of them have developed a rather special type of stroke to overcome it.

The essential club for this shot is a broad-soled sand-wedge; the essential attribute in the player is confidence, which comes from practice; and the critical part of the technique is to hit a little way behind the ball with an open clubface, as in a standard ‘splash’ shot from sand.

If you have rough close up to your greens, it would be worth experimenting with this stroke. Play the ball well forward, open the clubface slightly at address, make a slow and easy swing with plenty of arm action, the club going back a little outside the target line. Then swing the clubhead down a little way behind the ball – being sure to keep it going right through grass and ball.

What follows is a selection of other trouble shots you might encounter on the golf course.

Situation: You face a shot from a ‘tight’ lie. The ball rests either atop bare ground or well down in the grass.

Suggestions: In either of these tight-lie situations, your clubhead must first contact the low-lying ball, not the barren ground or too much of any grass that might be behind it.

To catch the ball first the most important impact condition to create is a fairly steep angle of approach. The clubhead that reaches the ball while still moving downward will have already passed over the bare ground or much of the grass, whichever the problem may be.

There are two excellent ways to steepen your club’s angle of approach. However, each tends to create an entirely different type of ball flight. One makes shots fly a relatively short distance on a rather high trajectory. The ball settles quickly upon landing. The other method produces low-flying, running shots that travel further overall.

I suggest that in any tight-lie situation you first decide which of these two types of shot you would prefer. Then apply the downswing-steepening technique that is more likely to create that shot.

The method of steepening your angle of approach that results in the high, short shot involves swinging the club through impact on an out-to-in path. First align your shoulders farther to the left than you normally would. Then swing the club parallel to that leftward alignment through impact.

To make this shot fly on target, rather than too the left in the direction you are swinging, open the face a bit to the right at address. Set your hands a little forward, to the left of the clubhead, as well. Maintain the open clubface through impact by making sure that your hands lead the clubhead into the hitting area. Because of the open face, you should allow for the shot to curve to the right except when using a highly lofted club. The amount of curve to plan for will increase with the length of the shot.

These shots usually fly higher than normal and settle quickly upon landing, because the open clubface increases loft. The added loft will make the shot fly a shorter distance, however, as will the glancing blow that comes from swinging to the left with the clubface opened to the right. Thus a 6-iron, for instance, might easily produce an ‘8-iron’ shot.

The second way to steepen your angle in tight-lie situations is, in fact, identical to the method I suggest for sand shots from fairway bunkers. In each case you should play the ball farther back to the right in your stance than normal. In each case you would set your hands well forward, to the left of the clubhead, in more or less their normal position relative to your left thigh.

This combination of ball back and hands forward, if maintained through impact, assures that contact will occur before the clubhead has completed the downswing portion of its arc. To further assure a descending angle of approach, address the ball with more weight on your left side and with your right shoulder slightly higher than normal. Swing the club up and down the target on a fairly upright plane, predominantly with your arms.

This shot will usually fly lower and run farther than normal because the ball-back, hands-forward combination ‘hoods’ (delofts) the clubface. That same 6-iron that I said might create ‘8-iron’ shots with the first tight-lie solution mentioned, might well produce ‘4-iron’ shots if you apply this second approach to the problem.

Situation: Your ball is in the rough, say 4-iron distance from the green. You would like to use that club so as to reach your target. However, you have found in the past that you do not contact the ball solidly on shots from rough with longer, less-lofted clubs.

Suggestions: This is another situation where the weekend golfer often wastes strokes. He bows to the temptation to go for the green with the club that he would normally use from the fairway at that distance. As it swings into the ball, however, the clubhead snags in the intervening grass. All too often the ball finishes far short of the desired distance.

I suggest that in this sort of situation you first choose a club with more loft than you would normally use, in this case say a 7-iron instead of the 4-iron.

Play the ball further back in your stance than normal (the deeper the lie, the farther back you should play the ball and the more-lofted club you should choose). Do not, however, set your hands any farther to the right than their normal position at address.

With your hands well forward of the clubhead, you will find it easy to swing the club more abruptly upward and downward than normal. The steeper angle of approach into the ball avoids most of the grass behind it and thus makes the impact more direct.

The better contact makes the shot go farther. So too does the fact that the 7-iron’s steep approach has, in effect, reduced its loft, perhaps even to that of the 4-iron you would have preferred to use in the first place.

Usually the shot will fly lower than you would normally expect from the club in hand. It will generally roll much farther, however, perhaps as far as the green. Therefore you should take into account beforehand the problems posed by intervening hazards.

Situation: Some object – perhaps a tree or bush – blocks your line to the target. It seems impossible to play over or under the object. The choice is either a straight shot safely away from the problem or a curved shot around it.

Suggestions: I find that this situation causes many golfers to attempt shots that cannot possibly succeed. The shot that they intend should curve flies straight or the intended straight shot curves.

The golfer blames his poor swing on bad luck. He resolves to get it right next time. But he will fail again and again, until he finally realizes that talent alone will not succeed on some shots in golf. There are certain conditions that make certain shots all but unplayable, even for a Jack Nicklaus.

Conditions affect what your club can do or cannot do to the golf ball: the ballistics of impact. I want to make you aware of these conditions so that you will not attempt to avoid the object in question with a risky or impossible shot but, instead, will play the shot that conditions more or less favour.

The conditions you should consider in this sort of situation apart from any crosswind or any slicing or hooking tendency you might have, are (a) the length of the shot, (b) the lie of the ball and (c) any sloping terrain in the immediate area.

Length of shot. All things being equal, it is possible to curve long shots in either direction. Since these shots call for a minimum of clubface loft, the contact will be high enough on the back of the ball to apply sidespin.

In most instances, however, impact ballistics favour playing the longer shots from left to right, not right to left. This is true because the right-to-left shot calls for an into-out swing path with the clubface closed to the left of that path at impact. Since the closed face delofts the club, the straighter-faced woods and longer iron clubs may not carry enough effective loft at impact to put the ball into the air. Therefore you must be sure to choose a club with more loft than you would normally select. A 5-iron, for instance, might actually translate into a 2-iron or 3-iron at impact.

Moreover, the long right-to-left shot requires an exceptionally good lie, since the in-to-out path makes the angle of approach very shallow, especially with the longer-shafted clubs. The ball must be sitting up perfectly so that the shallow-moving clubhead can contact it solidly without catching in grass or turf behind it.

Conversely, long shots can be played from left to right with far less risk. This shape requires an out-to-in path with the clubface open. The out-to-in path creates a relatively steep angle of approach so that the contact can be fairly solid even if the lie is less than ideal. Also, since the open clubface increases loft, it becomes relatively easy to get the ball well into the air with the straighter-faced clubs. The added loft will, however, reduce the length that you can expect from the club in hand.

Short shots played around an object are all but impossible to curve from left to right. The extra loft that results from the required open clubface, when added to the already highly lofted irons, makes contact occur well to the underside of the ball. This low contact puts so much backspin on the ball that it cannot be curved to the right.

It can be curved from right to left, however, thus making this the preferable shape on short shots. With the highly lofted clubs enough loft remains, despite the required closed face, to easily get the shot into the air. Moreover, with the loft decreased by the closed face, contact occurs high enough on the ball to apply the right-to-left sidespin needed to make the ball curve.

The lie of the ball. A good lie with plenty of grass under the ball simplifies playing a right-to-left shot but makes slicing more difficult. Conversely, as I have said, the tight lie on barren ground makes slicing relatively easy but renders the right-to-left shots practically unplayable.

When the ball sits high on the grass, the human instinct is to sweep it away with a relatively flat swing. This type of swing encourages the clubface to close rapidly in the hitting area, thus facilitating the right-to-left shape. Moreover, with the ball ideally situated on the grass, solid contact is possible despite the relatively shallow angle of approach that results from the in-to-out clubhead path.

When we have the opposite sort of lie, with the ball resting on barren ground, both human instinct and golf ballistics favour slicing.

First, we sense that it would be difficult to contact such a low-lying ball solidly if we made a flat, sweeping swing. Instead we tend to attack it with a somewhat steep angle of approach. This, in itself, tends to leave the clubface open at impact, just as it should be for curving shots to the right.

Second, as I have said, the open clubface needed for slicing also has the effect of increasing the club’s loft. This extra loft sends the ball well into the air despite the tightness of the lie.

The tight lie, however, all but disallows the right-to-left shot, other than with the highly lofted irons. This shape calls for a closed clubface and a shallow, in-to-out swing path. With the ball resting tight to the ground, the straighter-faced club cannot make solid contact with the bottom of the ball. However, since the shorter irons force us to stand closer to the ball and, therefore, swing on a more upright plane, it is possible to make solid contact with these clubs even when the lie is tight.

The immediate terrain. As a general rule, you will find it relatively easy to slice, and difficult to hook, when hitting from downhill terrain and/or from a sidehill with the ball below your feet.

You will find it easier to hook, and more difficult to slice, if the terrain on which you stand is uphill and/or sidehill with the ball above your feet.

Situation: You face a shot from sloping terrain.

Suggestions: Almost any slope, no matter how slight, will affect the impact conditions. You will need to adjust your address position and/or your swing to take account of these special situations.

The tendency is to hook the ball to the left on each of these sloping lies …

There are four basic types of sloping lie. There are the two sidehill situations, where your feet are more or less level with each other but higher or lower than the ball itself. And there are the uphill and downhill lies, where your left foot is either higher or lower than your right.

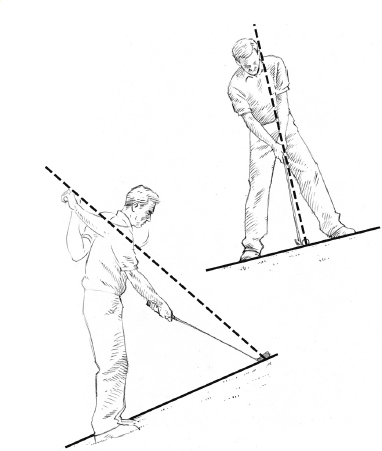

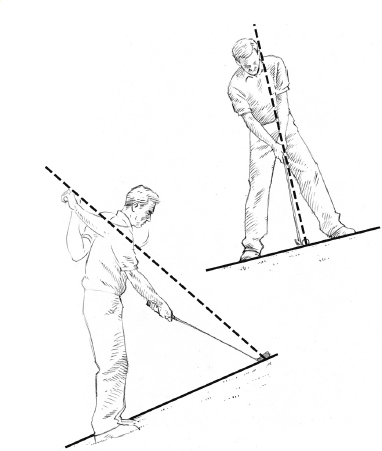

Uphill lie: Hitting up slope creates the need for an upward angle of approach. This approach makes the ball fly higher and stop sooner than normal. The hillside inhibits leg action and therefore restricts the clearing of the left hip during the forward swing. Instead, the arms and hands tend to take over and close the clubface to the left prematurely. (Adjustments: Choose a club with less loft than normal. Aim it to the right of target. Set yourself perpendicular to the slope, with your right side lower and your left side higher than normal. Swing down the slope going back and up the slope going forward.)

… Whereas on these two sloping lies, the hall will tend to slice to the right in its flight.

Downhill lie: The downslope requires a steeply downward angle of approach. This makes the ball fly lower and run farther than normal. It also tends to leave the clubface open to the right at impact so that the ball slices in that direction. (Adjustments: Choose a more-lofted club. Aim for a left-to-right shot. Set up perpendicular to the slope – right side higher, left side lower than normal. Swing up the slope going back, down the slope going through.)

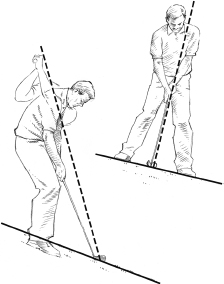

Sidehill lie (ball above feet): With the ball higher than the feet, you will need to address farther from the ball. This will create a flatter, more sweeping swing. The flatter swing tends to close the clubface to the left more abruptly than normal during the forward swing. (Adjustments: While standing on the slope, make several practice strokes until you can find and sense the flat, sweeping plane needed for solid contact. Then aim and align for a right-to-left ball flight and try to duplicate the flat swing that you sensed beforehand.)

Sidehill lie (ball below feet): A more upright swing than normal is needed for the clubhead to reach the bottom of the lower-sitting ball. The exaggerated upright swing, however, tends to make contact occur with the clubface open. (Adjustments: Stand closer to the ball and bend forward as needed for the clubhead to reach ball level. Aim and align for the shot to fly from left to right. Swing the club largely with your arms and hands on a particularly upright, straight-line arc.)

Situation: Going for distance out of sand.

Suggestions: The most important factor in going for distance from sand is correct club selection. So often I see players with the ball lying well back in a shallow bunker take a straight-faced club, then, in mid-swing, suddenly think they are going to catch the trap’s front lip. The inevitable result is that they try to flick the ball off the sand. That causes the wrists to release too early, widens the downswing, and brings the clubhead into the sand behind the ball. Disaster – always!

It is vital if you want distance from a bunker to hit ball first, sand second – just as one does with an iron from the fairway. To do that, it is imperative that you have no fear in your mind that you haven’t enough loft on the club to lift the ball over the bunker’s front lip. This is your limiting factor in the distance you can get from sand. You have to take the club which will, without doubt, clear the lip, even when you deloft it a little by positioning the ball farther back than normal towards your rear foot, with the hands three to four inches ahead of the clubface at address.

This set-up, with the weight predominantly on your forward foot, ensures that the ball will be hit first, sand second. From this position swing normally and forcefully, endeavouring above all to lead the clubface into the ball with your hands.

Never be overambitious on this shot. Err on the safe side.

My overall advice on bunker play is that you give a little time to practise it. Sand really isn’t the terror it seems to most club golfers. If you will spend an hour hitting shots from sand, I’ll guarantee your fear of it will disappear.