Four

I am on a train approaching Dordrecht (colloquially known as Dordt), the city to which Lien was brought in the late summer of 1942. Seen from the railway bridge before we pull into the station, its Great Church rises up between pretty gabled houses, beyond which lie harbors and a heavy industrial zone. Though small by today’s standards, with a population of around 120,000, this was once the biggest city in Holland. Built on an island that was created by a confluence of rivers, Dordt saw its heyday back in the fifteenth century, when it became a natural center for the handling of agricultural goods. For a while it was a merchant city. The silt-filled rivers, however, proved unsuitable for the larger ships that soon became necessary for ocean trading, which meant that, over time, Dordt was overtaken by its larger westerly neighbor, Rotterdam.

It was here rather than in The Hague that Dutch independence really started. In 1572 the city hosted the First Assembly of the Free States, at which William of Nassau, Prince of Orange, announced his open rebellion against the Spanish king. It was also here, at the Synod of Dordt, that the new republic, having proved victorious, decided on its state religion. From 1618 to 1619 the Protestant churches of Europe gathered to debate the great theological questions. On the one side stood the followers of Arminius, who felt that some kind of accommodation with Catholicism might be possible: perhaps grace (that great act of divine forgiveness for man’s innate sinfulness) could indeed be fostered by human action, such as penitence or good deeds? Opposing them were the Calvinists, who insisted on what they termed the total depravity of human beings. According to Calvin, only a small band of individuals, already chosen by God before the beginning of time, would be saved from damnation, no matter how fervently the others might try to join that “elect.” The synod ended in a Calvinist triumph and only four days after its conclusion the main protector of the Arminians, Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, was led to execution on the block. Total depravity was thus confirmed.

AFTER LEAVING THE FUNCTIONAL INTERIOR of the station, I look back over my shoulder at its classical facade and then head down the main street into town. My plan is to begin by visiting the small local war museum. It is only a short walk, first through an area of modern office blocks and then through a set of pretty medieval streets that are full of cyclists and shoppers. At this hour of the morning these are mostly retired couples wearing practical clothing such as jogging bottoms and zip-up raincoats in bright artificial colors, like purple, lime green, and pink.

The museum, which is located in a town house across from the old harbor, is like hundreds of others: a little faded and cramped, with overbright lighting so that nothing looks real. In the entrance hall, pride of place is given to an army jeep that stands in the middle of the foyer on a dais of artificial grass. Stiff mannequins sit inside it. Their clean helmets have tightly fitting chinstraps and they smile, eyes forward, like Lego men. Behind, there are maps showing the German landings and then the Allied liberation. Bold arrows show troop movements accompanied by numbers and dates. Elsewhere there are photographs and display cases full of weapons, documents, and medals.

Dordrecht was one of the towns that saw real fighting when the Germans invaded. Paratroopers were dropped at first light on May 10, 1940, to seize the bridges. The city had a garrison of fifteen hundred soldiers, but the Dutch army, which had not fought a real war for more than two centuries, was spectacularly ill prepared. Few of the men had received full combat training and much of their ammunition was locked in a central depot for safekeeping, so they had only a minimal supply of rounds. In the early hours, many of the defenders simply looked up to the sky in awe of the Junkers bombers. Others wasted their supply of bullets trying to shoot them down.

All the same, once the shock of the landing abated, there were pitched battles. On day one, dozens of German assault troops were killed or wounded and around eighty were taken prisoner and shipped to England just in time. Then on May 13, around twenty Panzers rolled into the city, of which fifteen were disabled at the cost of twenty-four Dutch lives. After just four days of fighting, however, Dordt, like the rest of the Netherlands, surrendered and the troops spent the last of their energy destroying their own equipment to prevent it from falling into enemy hands.

AS THE SOLE VISITOR TO THE MUSEUM, I feel a little intrusive. Around me the men who work here (I should imagine on a voluntary basis) are checking stock lists, cleaning objects from the display cases, and reorganizing the small library of books about the war. As I stand scanning the battered spines, I turn to a man in a blue shirt with white hair who is sorting piles of volumes at a desk. He looks up, pleased at my interest in history and still more so when I tell him about Lien and her journey here from The Hague. At the mention of Mrs. Heroma, who brought Lien to Dordrecht, a look of recognition crosses his face. He asks what information I have.

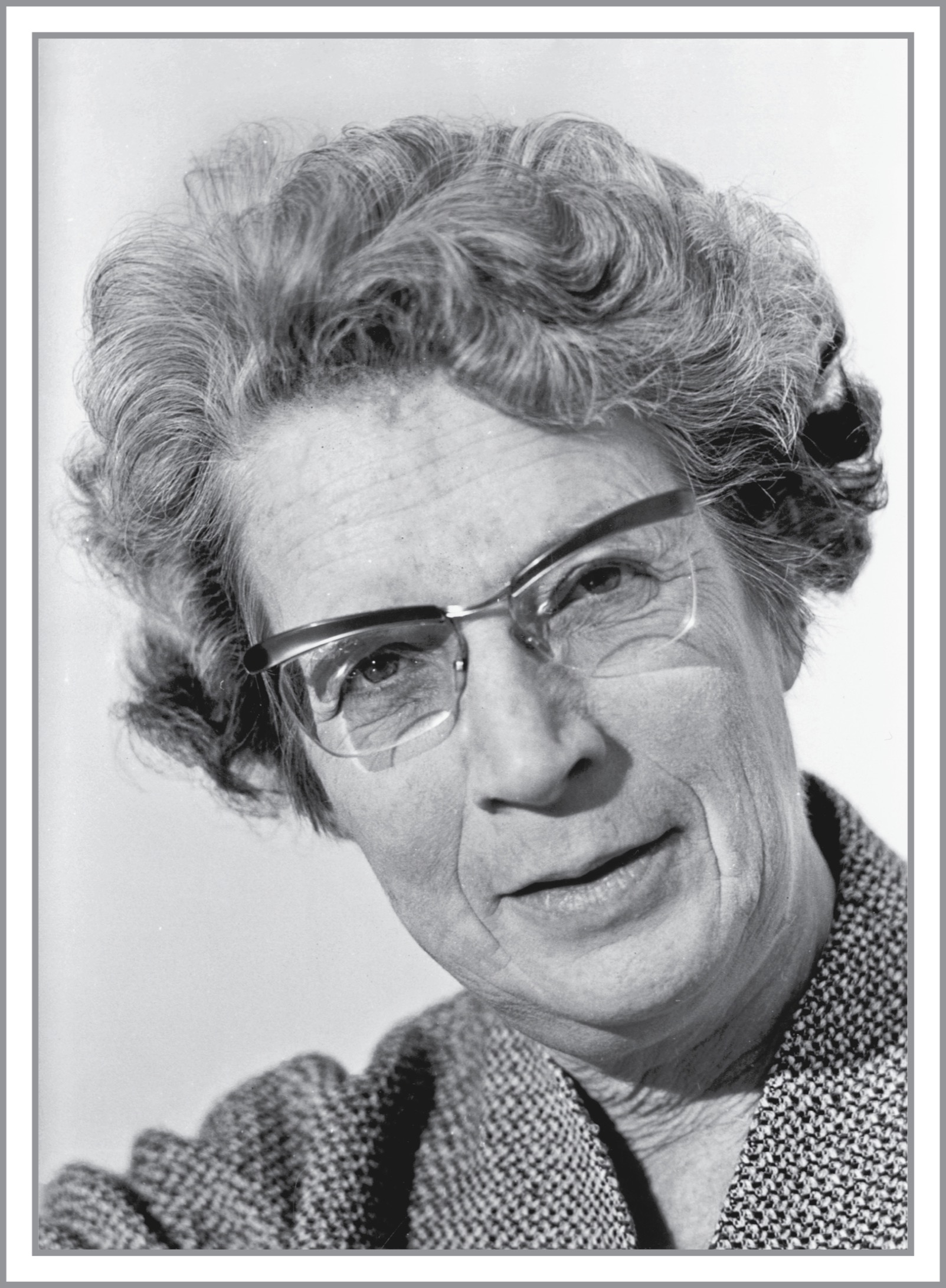

On my laptop, which I take from my suitcase, there is a photograph of a document: a yellow sheet of lined A4 paper covered in jottings, some crossed out. It is headed “What should play a role in the construction of a new law?” The document is in the hand of Mrs. Heroma, and I took the photo of it in Amsterdam. It came to Lien after Mrs. Heroma’s death. By the time these jottings were made, long after the war, Dieuke Heroma-Meilink (known as “Took” to her friends) was a Labor politician, first in parliament and then at the UN. The annotations on the paper are practical, with Lien cited only briefly as a case of an only child who had to join a larger family. A detail makes the situation human: as Lien’s mother pulled the front door shut at the Pletterijstraat, Mrs. Heroma heard her beginning to sob.

The man calls others toward him and soon a small group is looking over my shoulder at the document on the screen. As I scroll through the images on my computer—the poesie album, the letters, and the photographs—a strong feeling of shared interest fills the room. The one who really knows about this, I am told, is Gert van Engelen, a local journalist who also works for the museum. E-mails are sent and messages are left on answerphones and meanwhile the group checks indexes and databases, giving suggestions as to where I might go to find out more. They feel almost like friends. By midafternoon I have a list of Web sites and publications and am watching a video recorded by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum twenty-five years ago in which Mrs. Heroma, somewhat reluctantly, reveals the things that she and her husband did during the war.

IN THE 1930S the Heromas lived in Amsterdam, where Jan Heroma, having first completed a degree in psychology, was studying at medical school. The two of them were politically progressive, deciding to live together rather than get married, sharing a flat with the future socialist health minister Irene Vorrink (who was to become famous for decriminalizing recreational drugs in 1976). Having trained as a social worker, Took was employed by a trade union to provide political education for working-class women. At night in the flat, at a small desk with a typewriter, she translated German academic literature written by Jews into Dutch. This was necessary because, without these translations, German Jewish academics, persecuted at home by the Nazis, would find it difficult to find jobs in the Netherlands. To the Heromas, liberal, politically neutral Holland seemed a natural place of refuge.

By the time of the invasion, Jan Heroma had his own medical practice in Dordrecht, in an elegant white terraced house at 14 Dubbeldamseweg. An extra door had been fitted to allow patients direct access to the waiting room at ground level, and from there they could cross straight to the doctor’s study. The couple themselves lived in an apartment upstairs.

At first, the German invaders did little to disturb ordinary life in the Netherlands. They took over the reins of power (appointing Arthur Seyss-Inquart as Reichskommissar in charge of the civil administration), but the structure of government and the operation of services such as the police, the school system, shops, churches, and businesses remained more or less the same. Anti-Jewish measures ramped up over time almost imperceptibly: exclusion from air-raid shelters, an “Aryan Declaration” for members of the civil service, a requirement for the registration of all Jews. Then, from February 1941, mass arrests began, slowly at first. Those whom the Heromas had brought to apparent safety in their own country were now under threat, and the translations and new posts in the universities they had once provided were no longer of use.

From November 1941 onward, regular ads were placed in the bottom left-hand corner of the classifieds page of the local paper. Next to announcements from the dentist, the fashion boutique, and the concert hall, there were notices such as this:

J. F. HEROMA

PHYSICIAN

change of

consultation hours

On Krispijn at 11 o’clock

daily, apart from Saturdays;

PRIVATE CONSULTATION

daily from 1.30 to 2 o’clock

Where it mattered, people knew what these messages meant.

Across Holland, as the occupation gained in intensity, networks were being constructed to resist the Nazis: delicate lines of trust that connected couples like the Heromas in Dordrecht to distant others whom they had never met. These webs often clung to the holdfasts of prewar society, such as medical associations, student fraternities, churches, and political groups. Jan Heroma was a doctor and a member of the Social Democratic Workers’ Party and also the friend of many Jews in the academic world. This made the house at 14 Dubbeldamseweg a point of intersection. The little car that the Heromas owned made them unusually mobile, so that journeys between the houses of patients, sometimes far out into the countryside, traced fragile, invisible strands.

As Jan Heroma and his wife ferried people across the country and kept them hidden in their basement, others too were beginning to take action as part of networks in different towns. Jooske de Neve, for example, part of a resistance group called the Unnamed Entity, sat on trains from Amsterdam accompanying groups of children, herself shaking with a feverish headache of fear. Speaking long afterward, she recalled that she could always detect the moment at which other passengers recognized the quiet cluster of boys and girls as Jewish. She just had to hope that they would not tell. Once, a set of train guards began moving through the carriage, checking IDs and tickets. A wave of panic overcame her, and she ran to the toilet and flushed a pack of false identity cards (which she was ferrying in addition to the children) onto the tracks below. It haunted her conscience forever afterward that these false papers were found.

In Utrecht, Hetty Voûte, a biology student, joined a group that called itself the Children’s Committee. Searching for addresses to hide young boys and girls now separated from their parents, she cycled around the countryside calling at random on farmers for help.

As she stood at the gate of one farmhouse the owner told her, “If it is God’s wish that those children are taken, then that is God’s wish.”

Hetty looked straight at him. “And if your farm burns down tonight, then that is also God’s wish,” she replied.

Back home in the bookcase in her room she had a leather-bound volume with the title The Assembled Tales of John Galsworthy stamped on the spine. Within, there lay hidden a system of index cards that recorded the names and addresses of the 171 Jewish children she had saved.

Around the same time, in Limburg, at the southern tip of the country, another farmer was being presented with children to shelter, starting with a three-year-old girl who was left at his door. Looking back, one can see that it was hard for this man, Harmen Bockma, to keep his head above water. He already had a milk round early each morning and worked shifts at the local mine to make ends meet. To hide children he would need special spaces in his farmhouse, which would take money as well as time. And so, in order to get the paid leave from the mine that would be necessary for the work to be completed, Harmen Bockma cut off part of a finger from his own hand.

More stories such as these are to be found in the museum and in the Dordrecht municipal library. In a high-ceilinged café I talk with Gert van Engelen as he writes down e-mail addresses and phone numbers in my notebook and suggests places of wartime significance that I might visit beyond and within the town.

Two final stories stick with me. One is the case of Ger Kempe, a student doing the rounds in search of funding for a resistance group hiding children in late 1942. Having knocked at an unknown door, he was tentatively invited in by the old lady who answered it. Perched on a sofa in her sitting room, the young man delivered a speech that was met with awkward silence. The woman waited for a long time, giving no response, then eventually told him to come back in a few days’ time. When he did so, expecting little or nothing, the old lady gave him sixteen hundred guilders: a fortune that saved many lives.

The second story concerns a number of female students. By late 1942 the situation for the remaining Jews in the Netherlands had become utterly desperate, so much so that mothers were now leaving babies and young children on doorsteps in the hope that they would be taken in. The German authorities, aware of this trend, put out an official notice: from now on, all foundlings would be assumed to be Jewish and even those who had earlier been accepted and adopted by Aryan families were to be hunted down by the police. The group of young students could see only one solution. They would register Jewish babies as their own children, fathered by German soldiers. This would bring the certainty of safety, but also, of course, tremendous shame to the women themselves. Years afterward, An de Waard retold the story of her experience at the registry office, where she was made to wait on public view for a very long time. Eventually, under the clerk’s contemptuous gaze, she was able to register the child as William, a royal name, which for her was a little gesture of resistance. Like the five other babies saved in this manner, William survived the war.

MEANWHILE, IN DORDRECHT, the Heromas continued to ferry, to care for, and to hide Jews of all ages, although they were increasingly fearful that their activities were being tracked. Once, Jan Heroma headed out to look after a sick Jewish woman in hiding who, in spite of his best efforts, died of natural causes after several hours. As there was no way to remove her body without its being noticed, he dug a secret grave for her in the back garden under cover of night. In another case, he and Took rushed out to a house that had been hit by Allied bombing, aware that a Jewish couple was hidden inside. They guided the couple back to the Dubbeldamseweg, where they hid them in the cellar. After this, Jan went out in his little car to fetch the bombed-out couple’s daughter, who had been taken to a farmhouse far away. At first the girl, long separated, did not recognize her mother. Then, when she suddenly did, her delighted screams of recognition brought terror of discovery to the house.

For months all went well, but then one night there was a knock at the door. A group of policemen stood waiting outside. In the dead of night, with Jews still hidden in the cellar, Jan Heroma was led away to prison and an uncertain fate.

DURING MY TIME IN DORDRECHT I visit many places, but it is only toward dusk on the final day, just before taking the train back to The Hague, that I head to the Bilderdijkstraat to see the address where Lien first arrived in the town. It is a ten-minute walk from the station, so I go there trundling my suitcase, first through the park in the weakening sunshine and then along the broad pavements of a suburban trunk road that is beginning to fill with commuter traffic.

The Bilderdijkstraat itself is narrow and rather gloomy. For the first fifty yards both sides of the street have high, gray panel fencing that is faded and marked by graffiti tags. After this, on the left, it opens out onto an urban playground filled with the smooth-edged concrete of bicycle and skateboard ramps. I come to a halt and look out at the empty swings and slides, which are of a high-quality polished metal that makes them look like abstract works of art. A few trees grow on little islands of gray soil surrounded by asphalt, but there is no grass. About half a dozen teenage boys of North African appearance sit chatting, perched on the seats of their bikes. Across the way, a corner shop advertises cheap international dialing and halal meats.

Since the 1970s the Netherlands has become a country of immigration. One fifth of the population was either born outside the borders or are the children of those who were. Integration, especially among the two million that are of non-Western origin, has, on the whole, been only moderately successful, and that feeling of isolation is evident on this street.

Looking for number 10, I begin scanning the doorways, my suitcase clunking on the pavement slabs. Toward the end of the road there is a block of new terraced housing, different from the low-rise brick tenements that surround it. Some of this is occupied, but other parts have steel grilles over the windows that seem to have been there for a good while. The new build has confused the number system, so I end up walking along the same stretch of pavement again and again. While the boys on bicycles are in no way threatening, they regard me with increasing interest as an oddity, as well they might.

By the time I decide that number 10 stood on what is now the playground, the sun is casting long shadows across the street. I reach for my phone and take a few pictures, first of the concrete skateboard ramp with the spindly trees around it and then of the row of houses that stands opposite. The entire terrace is a single flat-roofed unit. It is as if its long front wall was rolled in some factory and then had windows and doors punched out of it by an enormous machine.

As I return the phone to my pocket, a door opens and a middle-aged man in a kameez comes toward me asking suspiciously, with a heavy accent, what I am doing. Meanwhile, the boys on bicycles begin to hover round. Faced with their questions I am suddenly evasive, explaining in a vague manner that I am conducting research about the Second World War.

Why is it that I do not tell this man about Lien as I did at the Pletterijstraat? I have done so at addresses across Dordrecht, where I have sat happily chatting in people’s front rooms over the last few days. Why do I feel guilty here?

It is because I sense a distance between us. It is because I assume that Jewish history will not be welcome in this place.

“You ought not to be spying on people,” the man tells me, and as he says this I suddenly see myself from the outside, with my wheeled suitcase and my phone camera, and my scuffed, expensive, brown leather shoes. Perhaps if I had told the full story this might have forged a connection? Instead, we retreat away from each other, equally nervous, and I head out again toward the commuter traffic on the main road where the cars have now switched on their lights.

Walking back to the station, I am reminded of the obvious fact that the Muslim community, in terms of the hatred directed toward them, is probably closer to the Jews of the previous century than any other. There are no easy parallels, but all the same, the language of Geert Wilders (whose Party for Freedom has hit 15 percent in national elections) has an air of the 1930s to it. According to Wilders there should be a ban on the Koran and on the building of mosques. He has called the Prophet Mohammad a “pedophile” and he calls Islam “evil.” He has spoken of the threat of an “Islamic invasion” and wants no more Muslims to enter the country at all. He has even demanded the abolition of Article 1 of the Dutch Constitution, which outlaws discrimination on the grounds of religion. It is hardly surprising, given this background, that the inhabitants of the Bilderdijkstraat should feel suspicious. All the worse, then, that I came here trundling a suitcase, pointing a camera, only to look and not to tell.