CHAPTER 8

Gardens and Garages

FIG 8.1: The front garden was the pride and joy of many suburban house owners. It was their public display and was maintained to impress visitors and passers by. The garage to the side was a display of wealth and modernity even if there was no car within it!

It seems strange that for a country so addicted to gardening, it should have developed as a widespread hobby so late. The reasons are partly obvious in that it was not until the 1930s that houses with a spacious front and rear garden were standard, and there was little scope and extra cash for most working class families to be interested in turning over the small back yards on their Victorian terraces. Yet even in the larger middle class houses, until the later 19th century, gardening was a hobby below the standard of the lady or gentleman of the house. In fact, most large terraces built in the 18th and early 19th centuries had no back garden – that was the space for service buildings and mews, and a communal private strip at the front overlooked from a balcony was the only greenery.

FIG 8.2: The rear of a Victorian terrace (right) and an inter-war local authority house (left) showing the vast improvement made for working class families who now had hedged gardens with lawns and borders rather than just a hard-standing yard with a rear extension housing the privy!

Part of the drive to improve the aspect of the house came from the garden city movement before the First World War, in placing the importance on spacious plots and ample foliage. This was taken up in the inter-war years on local authority and speculative-built housing estates, if only because the suburban land was cheap and the garden was a good selling point.

The suburban gardens also gave families the opportunity to grow their own food. The Victorian working classes had not been keen on fruit and vegetables, the main improvement they sought in their diet was meat (jam was promoted in the late 19th century partly to increase consumption of fruit). The gradual improvement and changing diet was aided by improved access to land especially allotments on vacant industrial, urban and railway sites, and the reduced cost of produce in the shops. Now in the inter-war years it became common for the far end of the garden to be closed off to grow your own vegetables.

Front gardens

The front garden was a status symbol, giving the house a more rural aspect and creating more privacy for the family. It was proudly displayed and maintained by most new owners, especially as it was on show to passers by, although the limited space meant that it typically featured little more than path, flowerbeds and a section of lawn.

Fences and walls at the front tended to be low when first fitted. Builders might provide a privet hedge, simple post and wire or picket fencing with, on some of the better examples, low brick walls with metal rails or a wooden fence on top.

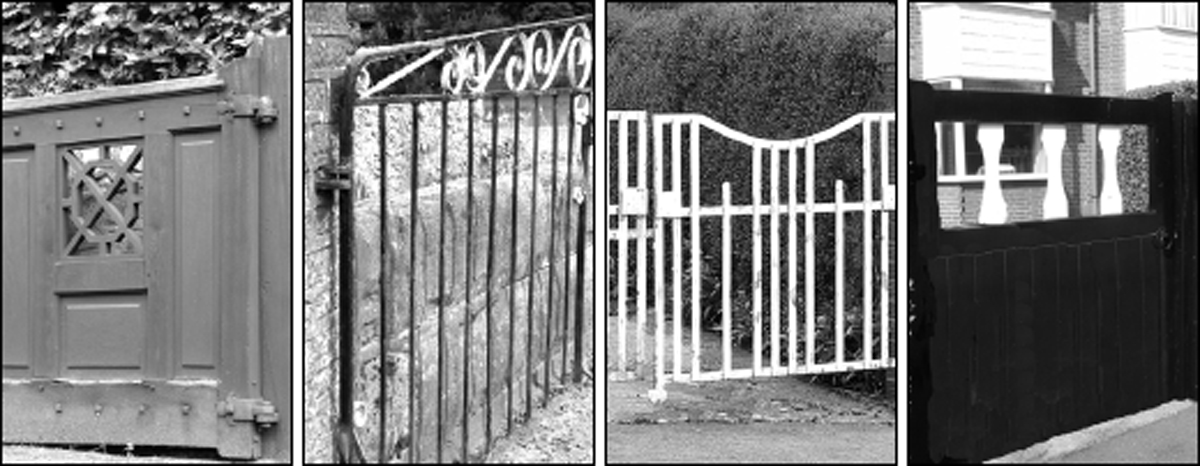

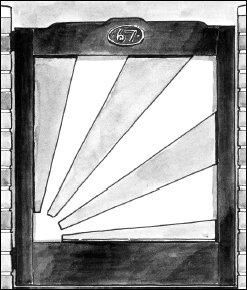

The gate was an important feature as it was the first part of the property seen and touched by visitors. Metal-framed and wooden picket gates were popular although the most iconic image is of the central portion shaped in the sunray pattern.

FIG 8.3: Examples of metal and wooden gates from inter-war houses.

FIG 8.4: The sunray design was one of the most popular and iconic designs for the front gate.

Rear gardens

One of the most notable changes that came with the increased popularity of the garden was the appearance of the rear of the house. Gone were the outbuildings and cramped rear windows now that kitchens and sculleries were housed within the main structure or hidden to the side. The small rear window was replaced by large French doors as the garden became an extension of the house. The appearance of the rear façade, which formerly had been a neglected face of common bricks, could now be as impressive as the front, with bay windows and balconies on what had become known as the ‘garden front’. Conservatories had somewhat gone out of fashion with the decline in interest in exotic plants in the late 19th century, but now types of wooden and glass lean-tos were built on the back of some houses.

The design of the rear garden was generally formal with a paved patio directly behind the house, a lawned area edged by flowerbeds beyond this, and a vegetable patch usually enclosed behind a high hedge at the far end. The more expansive gardener might venture to have a rockery or a pond.

FIG 8.5: A photograph showing how the rear of houses changed in the early part of the 20th century. The late Victorian terrace houses in the right foreground have rear extensions, which would have housed a scullery, WC and stores with no attempt to link the house to the garden. The later semis on the left of the picture date from the inter-war years and have bow windows and French doors overlooking the rear, with this new garden facade as elaborate as the front.

FIG 8.6: A plan of a house and gardens showing typical layout of the rear garden.

The perimeter was marked out with higher fencing than at the front, usually wooden-boarded or a privet hedge, although simple wire and post or boarded fences were fitted on some cheaper housing. A shed, workshop, or greenhouse, usually hidden up the far end, was often added by owners. The storage of coal and the ash it produced also had to be catered for. Coal was often stored in the house structure, either in a small store off the rear lobby or under the stairs accessed by a door up the side of the house. If it was kept outside then a bunker or brick outbuilding would have been provided along with an ash bin. You can see why electric and gas heating were so welcomed with all the problems associated with coal fires!

Garages

The car industry boomed in the inter-war years yet the ownership of motor vehicles was still limited to the reasonably wealthy. Most people could happily get by with rail, bus, tram or bicycle, and on foot. Having a garage was therefore seen as a symbol of wealth and modernity, and many bought houses with them even if they didn’t have the car to go in it.

This high status is reflected in the build and design of the garage. It was not simply a box with a lift-up metal door. The 1930s garage was often brick-built and decorated with the same care and attention as the house.

They could either be built onto the side of the house, usually with an extra bedroom above, or be a separate structure on the side or tucked up just behind the house. In the latter case they might be brick with a tiled roof and perhaps some timberwork in the exposed gable above the door, or simply a concrete slab or timber-walled structure with asbestos roofing. The doors were wooden, folding types usually of four or six hinged sections with small glazed openings in the top third (six windows was typical).

FIG 8.7: Examples of garages from inter-war houses, from those built into the structure of the house with an additional room above, down to simple free-standing concrete slab types.