Never assume that people who like to live an organized life don’t know how to enjoy themselves. With a mixture of Catholic and Protestant traditions, the Germans have a wide variety of festivals, customs, and celebrations, some of them pretty lively. It’s also worth remembering that many popular Christmas traditions—Christmas trees, decorations, and cards—were actually introduced to Britain by Queen Victoria’s German consort, Prince Albert.

The key national festivals in Germany vary according to the state. There are ten national public holidays in all of Germany, and some others that are celebrated in only a few, mainly Catholic, states.

GERMAN FESTIVAL |

ENGLISH NAME |

|

January 1 |

Neujahrstag |

New Year’s Day |

March/April |

Karfreitag |

Good Friday |

March/April |

Ostermontag |

Easter Monday |

May 1 |

Tag der Arbeit |

Labor Day/May Day |

May/June |

Christi Himmelfahrtstag |

Ascension Day/Father’s Day |

May/June |

Pfingstmontag |

Whit Monday, Monday after Pentecost |

October 3 |

Tag der Deutschen Einheit |

Day of German Unity |

December 25 |

Weihnachtstag |

Christmas Day |

December 26 |

Zweiter Weihnachtsfeiertag |

St Stephen’s Day (Boxing Day) |

December 31 |

|

New Years’s Eve, Bank holiday |

|

|

|

The main annual celebration is Christmas. For weeks before December 25, the date that commemorates the birth of Christ, there are Christmas markets in town centers selling festive decorations, food, and wine. These have become popular with the coach-tour market, and coach parties from Britain, France, Belgium, and Italy now converge on German towns to enjoy the pre-Christmas festivities. One of the most famous of these is the Christkindlesmarkt in Nuremberg (Nürnberg). At the Christmas market you can buy mulled wine (Glühwein), gingerbread (Lebkuchen), and also spicy Christmas cakes called Stollen. Choirs and brass bands sing and play Christmas carols.

A month before Christmas, the children start to open their Adventskalender (Advent calendar). The season of Advent, the four weeks leading up to Christmas, is a time of spiritual preparation for the faithful, and the Advent calendar contains a series of pictures illustrating Christmas themes, each concealed behind a scored paper door. The children open a new door every day to see what lies behind it during the run-up to Christmas.

Making one’s own Christmas decorations is still popular in parts of Germany. In school, kindergarten, and even at home, children, teachers, and parents make decorations for the room and the Christmas tree. Another tradition observes Advent with a special wreath with four red candles called an Adventskranz (Advent wreath), one to be lit on each Sunday before Christmas.

On December 5 children leave out their (clean!) shoes when they go to bed (in some regions also socks). During the night St. Nikolaus (Father Christmas, or Santa Claus), is supposed to visit. If you’ve been good he leaves sweets, and if you’ve been bad he leaves twigs. On December 6 in many areas a man dressed up as St. Nikolaus visits schools and kindergartens. Children sing songs and, if they have been good throughout the year, are rewarded with sweets, nuts, oranges, and apples. He is followed by St. Nick’s little helper, with a birch rod and a sack to carry away the naughty ones!

In Germany the Christmas family celebration takes place on Christmas Eve, December 24. Shops and offices close at midday, the family shares a light meal, and presents are exchanged round the Christmas tree. Who brings the presents? In north Germany it is Weihnachtsmann (a Father Christmas-like figure) and in south Germany it is the Christkind (represented as an angel). Traditionally families attend midnight mass on Christmas Eve.

By contrast, Christmas Day is a going-out day—families visit each other and youngsters play sports or go skiing. It is the equivalent of the British Boxing Day. By the way, the traditional German Christmas fare is goose with potatoes or dumplings and red cabbage rather than turkey.

December 31 is New Year’s Eve, and New Year’s Day on January 1 is a public holiday. It’s a noisy affair with champagne and fireworks everywhere. Bells are rung in the churches to usher in the New Year, and in some places hot lead is dropped into water and the resulting strange shapes used to tell fortunes. Good luck charms may be exchanged, containing marzipan or chocolate images of horseshoes, ladybirds, four-leafed clovers, or even chimney sweeps and little pigs.

On January 6, the feast of the Epiphany celebrates the visit of the three kings to the stable where Christ was born. Called in German Heilige Drei Könige (Holy Three Kings), it is the occasion for children and teenage boys to dress up as the three wise men and go from door to door collecting money for charity. They generally get sweets or candies as their reward. By the way, you may notice inside some doorways the chalked letters CMB. These initials, which stand for the Latin expression “Christ bless this house,” show that a donation has been made to Sternsinger-Aktion. “Sternsinger” (Star singers) are youngsters from local churches visiting houses with the C+M+B sign to solicit donations for charities such as the World Children’s Fund Deutschland, the second biggest in Germany after the Deutsches Rotes Kreuz (German Red Cross), helping children in poor countries. They even pay an official visit to the Chancellor, who also donates to the charity.

Ash Wednesday, in Catholic parts of the country, signals the beginning of Lent, the period of fasting and purification leading up to Easter Sunday. The Sunday and Monday before Ash Wednesday is the time for Karneval (Carnival) in many towns and villages. Preparations for this start months before. The season begins on the eleventh day of the eleventh month at eleven minutes past eleven o’clock in the morning (on St. Martin’s Day).

Karneval is a time of conviviality and informality, when the normally formal Sie (you) becomes the informal du for a short while. There are parties in offices, schools, and at home. People dress up in wild fancy-dress costumes and in the large cities there are big street processions.

Festivities reach their climax on Rosenmontag (Rose Monday), two days before Ash Wednesday. This is the day of the main Karneval parade, presided over by the Karneval “prince” and “princess.” On the final day of Karneval, on Tuesday, there is no fasting but celebration and eating and drinking—the equivalent of Shrove Tuesday or Mardi Gras in Britain or the United States. Weiberfastnacht (women’s fasting night) is on the Thursday before Rosenmontag. On this day women rule the city and have the right to cut in half the tie of any man they see. They actually do this, so if you are in Germany at this time be sure to wear an old tie!

In Munich Karneval is called Fasching. It is also known as Fastnacht, Fasnet, and Fosnat.The biggest and best celebrations take place in Düsseldorf, Mainz, and especially in Cologne.

Easter has its own traditions. The Osterhase (Easter rabbit) hides painted hard-boiled eggs for the children to hunt. The Sorbs (south of Berlin) are famous for their beautifully decorated Easter eggs. People exchange chocolate Easter eggs or chocolate rabbits. Those who have gardens bring in bare branches and decorate them with Easter flowers and other decorations. The Easter rabbit is a relic from the old pagan festival of the spring solstice, held to celebrate the renewal of the fertility of the land with the coming of spring after the sterility of winter.

The Easter church service itself follows the Crucifixion and miraculous Resurrection of Jesus Christ. On Good Friday, the church is empty; the statues of the saints are covered in black or purple, and only the twelve Stations of the Cross—paintings, reliefs, or statues around the walls of the church depicting Christ’s suffering and death on the cross—are left uncovered. A ceremony of prayer in front of each Station is observed. There are no flowers, no music at night, and no decorations. On Saturday the churches are closed during the day, except for private prayer, remembering the time Christ spent in the tomb. Then the covers are off, and the churches are filled with candles and flowers for the mass to celebrate Christ’s Resurrection.

Germany’s Baroque churches, all gleaming white and opulent color inside, are beautiful places at any time, but have a special radiance on Easter Sunday.

This pattern of decoration and celebration occurs with many saints’ days, especially in rural areas. On St. Martin’s Day in November, children carry paper lanterns through the streets. On Corpus Christi Day (observed on the Thursday after Trinity Sunday), in Catholic areas, processions are held and outside altars erected and decorated.

The tradition of decoration extends to nonreligious occasions. For example, in the Richtfest, or topping-out ceremony, when the shell of a new building has been completed, flowers, ribbons, and greenery are attached to the beams before the roof is put on. Traditionally, a barrel of beer is tapped and other refreshments are offered by the owner.

On the first day of primary school parents give their children a Schultüte. This is a cardboard cone full of sweets, candies, pens, toys, and books that is intended to sweeten the child’s entry into school. Sometimes these are almost as big as the children themselves.

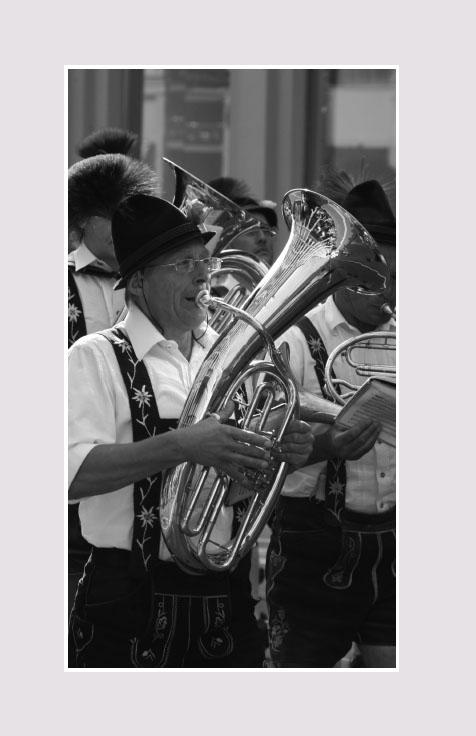

The Oktober festival centered in Munich is really a beer and wine harvest festival. It lasts for sixteen days, from late September until the first Sunday in October, and is the largest folk festival in Europe. It started with the marriage of King Ludwig of Bavaria to Princess Theresa of Saxe-Hilburghausen. During the wedding celebration people drank beer and wine in enormous tents erected in the Theresienwiese field. This is the time you will see men in Lederhosen (leather pants) and women in Dirndl (petticoated pinafore dresses), and the Trachtenfest parade of beer wagons pulled by shire horses.

On board a decorated brewery float.

An important tradition in Germany is the Messe, or annual fair. This may be either a trade or a craft fair. The Messe grew out of the traditional country market where agricultural produce was exchanged, with certain areas specializing in particular produce. There are still weekly farmers’ markets in many cities. Hamburg’s fish market is famous.

The Messehalle (trade fair hall) is a feature of many of Germany’s great cities, and some of the biggest fairs are international events, such as the Frankfurt Book Fair in October, and the Hannover Messe, the world’s leading industrial technology trade show, in April.

For Germans a common or shared interest has always been an important reason for coming together in groups, and throughout German history there have been formations and reformations of ties between the disparate cities and states that helped them overcome to some extent the insecurity of their isolation. One such association, we have seen, was the Hanseatic League, a union of leading North Sea and Baltic coastal ports to coordinate their trading activities.

In Germany, it is common on your birthday to take cakes or candy into the office to celebrate with everyone or, if at home, to keep open house that day and entertain guests. As a guest, when arriving, just a handshake and congratulations will be enough, but you should perhaps take a small present or bunch of flowers. Be careful not to give presents before someone’s birthday—it is considered bad luck.

The familiar stag and hen nights, when bride-and groom-to-be go off separately with their friends for one last night of freedom, have only recently been observed in Germany. Traditionally, the couple invite friends to the bride’s house for a Polterabend, a jolly social gathering, of which the highlight is the smashing of crockery. Rather than trashing a hotel dining room or restaurant, this means breaking crockery usually collected for just this event.

On the wedding day itself the bride might be abducted by friends of the groom for a while during the ceremony. Note that wedding rings are worn on the third finger of the right hand, and engagement rings on the third finger of the left hand.

For most people in the US or Britain, Thanksgiving or Christmas is the time for the whole family to get together. In Germany Christmas Eve is really for the immediate family only, so Familientreffen (large family gatherings) once or twice a year become important occasions for meeting and catching up.

One of the many pleasures of life in Germany is the celebration of historical events. All the way down the Rhine in summer you can enjoy son et lumière (historical shows using sound and light) and fireworks recalling how such and such a castle was sacked and burned. A defeat is just as much a reason for celebrating as a victory! Or, more importantly, a great celebration of deliverance, such as the passion play at Oberammergau.

Oberammergau is a phenomenon. In 1634 the plague came to the village of Oberammergau in Bavaria. The villagers prayed to God and vowed that if the community were spared they would perform a Passion every ten years in thanksgiving. It was, and they did, and the Oberammergau Passion Play, performed every ten years since (except during the war years), has become a major cultural event. All the parts are played by the villagers, and the Passion is played out over a five-day festival. It is a remarkable and moving tribute to Oberammergau’s history, sense of continuity, and sense of theater and celebration.

There is no state religion in Germany, but some 70 percent of Germans are Christian, with a roughly fifty–fifty split between Protestants and Roman Catholics. The Germans are no more or less devout than other Europeans, but the State does subsidize the Church for certain charitable services. This subsidy takes the form of a mandatory Church tax (or Kirchensteuer) of 8 percent of one’s income for religious communities (churchgoers) in Bavaria and Baden-Wurtemberg and 9 percent elsewhere. Thus whatever you may state on a form that asks for your religion, even though you may not be a churchgoer, you are liable for tax.

Christian roots are deep in Germany. Christianity was imposed when Charlemagne became Holy Roman Emperor in 800 CE, and it was reinforced by the German states’ close relationship with Rome. Northeastern Germany was home to one of the most famous Christian military orders, the Teutonic Knights, who made it their crusade to convert the pagans of the Baltic region. Such was their success that knights came from all over Europe to campaign with them. The Order was disbanded when in 1525 its Grand Master converted to Protestantism.

Once Martin Luther had started the Protestant Reformation in 1517 by nailing to the door of a church in Wittenberg his objections to the excesses of the Catholic Church, Germany could well have become completely Protestant. During the Thirty Years’ War between the Holy Roman Emperor and some of the Protestant states, however, the southern German states asserted their loyalty to Rome and the region has stayed predominantly Catholic ever since.

The office of Holy Roman Emperor was both religious and secular, and committed the holder to defend the interests of the Church. By the time of the Thirty Years’ War the title had ceased to be elective and become the birthright of the Habsburgs. As a result the Empire came to be based on Austria and the Habsburg territories of Hungary, Bohemia, and southeastern Europe, until its abolition in 1806. The quasi-mystical significance of the Holy Roman Empire lay in its linking of the Roman Empire of antiquity, the Catholic faith, and allegiance to the Pope in Rome. For much of Germany, as opposed to Austria, however, its authority became meaningless from the sixteenth century onward.

The Cathedral of St. George towers over the city of Limburg in the state of Hesse.

The rise in immigration from the Middle East and North Africa has also seen a growth in the Muslim population of Germany, now estimated at about 5 percent of the total population. A large part of the German Muslim population was made up of “Gastarbeiter” (guestworkers) from Turkey and other countries, who have more recently been augmented by Muslim refugees and migrant workers. The president of Turkey, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, is committed to building mosques in Germany and Turkey currently controls more than 900 mosques.