The quality of English-language education in Germany means that almost everyone you meet will speak English more than adequately, even if they answer “ein Bisschen” (“a bit”) to the question, “Do you speak English?” But, perhaps because they don’t feel foreigners make the effort, Germans will respond with more than usual warmth if you can just greet them in German and say “Grüss Gott,” in Bavaria, or “Guten Morgen,” “Guten Tag,” or “Guten Abend” in the north.

German is spoken in Germany, Austria, in the German part of Switzerland, and in the far north of Italy (Tyrol), as well as in small enclaves around the world. It is no longer a world language, but in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries it was the language of enlightenment, science, scholarship, and liberal values, and German researchers, thinkers, and philosophers led the world. Up to the 1990s it was the second language taught in Russian schools, and it appeared on menus and bilingual documents in Russia until its recent replacement by English.

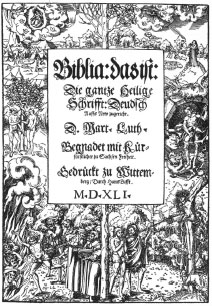

If you see older books in German you will notice that they are often printed in a Gothic typeface, once common but now almost totally abandoned in favor of the standard Roman script.

Frontispiece of the Luther Bible, 1541.

A branch of the Indo-European family of languages, German grew out of the languages spoken by the northern Asiatic tribes that migrated westward 2,000 years before Christ. It is related to the Scandinavian languages, Dutch, and English. Scholars have claimed to find German words in runic inscriptions on monuments, but the first recorded document in German is a Bible from the eighth century CE. The influence of Luther’s translation of the Bible contributed greatly to the development of modern High German.

German children learn standard High German, or Hochdeutsch, the educated language of German-speaking peoples, but several regional dialects exist. Chief among these are the Plattdeutsch of Friesland and the Frisian islands in the north, and the Switzerdeutsch of the German-speaking cantons of Switzerland. The differences are of accent and vocabulary with some small grammatical changes, but the dialects are mutually comprehensible.

The Germans value clear verbal communication and focus on the content rather than on the relationship. This is especially true in business. To the Americans and British, who are also content focused but place increasing emphasis on the relationship, this style of communication can seem overly serious. That said, there is much more common ground between young Germans and the youth of other countries brought up in an international pop culture.

Another factor influencing the Germans’ communication style is education. Middle-class, educated Germans are taught to be clear, fact based, and also quite analytical. This means that they take matters seriously, and accept that if a subject is serious it can be complicated. While the whole thrust of American and British communication is toward directness and simplicity, German communication is often academically precise and involved. As a result, the Germans often complain that American and British comments are simplistic, whereas the English-speakers complain that the Germans are unnecessarily complicated.

The Germans strive for objectivity, and can do so ferociously. In the process their attempts to get at the truth and to examine issues in great detail can come across as demanding and even aggressive. As we have seen, presentations can be followed by alarmingly probing questioning if taken seriously. The focus on content and the effort to analyze its key features means that the discussion can get quite forceful. Once again, don’t assume that people are getting angry; it is the tone of animated discussion. When the discussion is over the normal tenor of communication will resume. English-speakers are sometimes shocked by what they think has been an expression of personally directed anger. The lesson is, don’t take it personally.

The same applies to written communication, especially e-mails. The Germans will express themselves firmly and even strongly when disagreeing or rebutting an argument and then be surprised by the frigidity of response they receive from their British or American colleagues.

German directness therefore directly affects the use of language. Whereas English-speakers commonly downgrade the directness of communication by using “would,” “could,” and “perhaps” (the British more than the Americans), the Germans, by contrast, will upgrade the directness of communication and use what seems to non-Germans quite strong language. They will use, even in English, words like “definitely” and “absolutely” more often than would be expected.

Frank to the Point of Bluntness

A British manager proposed to his German counterpart that a special discount be offered to a branch in Switzerland. He was surprised by the, to him, exaggerated response from Germany, not only telling him in no uncertain terms that this was not appropriate, but giving him an analysis of the relationship that made clear that this kind of decision was not within his competence or part of his responsibility. The British executive felt rudely and badly treated, and was quite frigid when he next met his German colleague. The German was his normal charming self, mildly concerned that his British colleague was having an “off day.” A British or American executive would normally have been much more polite in telling his German counterpart to “butt out.”

At the same time, the Germans see no reason to “fudge” instructions. Foreign executive secretaries in German companies take time to get used to the directness of Germans who walk into their offices and say, “Give me that file, please,” rather than, “Hi Carol, how’s it going? Could I have the … file, please? Thanks a lot.” For a German the social padding is a waste of time.

English-speakers tend to avoid “must” and “should” as they might cause offense. The Germans often don’t realize this, and in translating directly into English from “müssen” and “sollen” they can quite unintentionally come across as overbearing. At the same time, the Germans don’t shy away from a direct contradiction. “Doch,” the German equivalent, of “Yes, but …” is often used to contradict flatly what has just been said. A native English-speaker would give credit to the previous thought by saying something like, “I see what you’re saying, but …” before expressing disagreement and counterargument.

It is important to recognize when communicating with Germans that what we consider rude or inconsiderate may actually be perfectly acceptable in German discourse. If you are about to take offense at something said or written, ask before you get angry. If an e-mail or letter upsets you, get on the phone and question what was meant before you respond with anger or criticism. Remember that the Germans focus on the communication rather than on the person, whereas for the Americans and British the person is as important as the communication.

German wit and repartee can be quick and very funny. However, the Germans do not feel it is necessary to tell jokes to get a message across. On the contrary, in business they can find it quite destabilizing. In school and at university German children learn to be as objective, serious, and impersonal as possible. This carries on into adult life. The German attitude is that if it is business, it needs to be taken seriously, and the American practice of using jokes as audience warm-ups, or the British use of humor to get over awkward moments in a meeting, can easily have the opposite effect on German decision makers.

Once again, attitudes can vary between older and younger members of the group, but be aware that the prevailing wind favors humor between meetings, not during them.

The German way to solve a problem is first to analyze it in depth. The Anglo-American approach is more pragmatic: form a hypothesis and find a solution. Obviously analysis enters into both processes, but the Germans are taught to do it far more thoroughly and in greater detail. This is, once again, school training at work. The Germans have a word for it—vertiefen, going into depth. At bottom, this represents a belief that things are not simple; subjects need to be analyzed and pursued consistently until clarity is achieved. This entails speaking precisely, defining problems exactly, and being literal and scientific in approach. It also means sticking with the subject until you’ve got a result. This determined search for truth can get quite confrontational.

This analytical approach isn’t just a business style. It’s a lifestyle. German friends will expect to talk about politics, philosophy, and attitudes to life and social issues. They will expect clarity. They will expect to reprove friends who they feel are not thinking things through, behaving inconsistently, or letting themselves down, and they will treasure directness and honesty rather than give each other an easy ride if they are wrong just because they are friends.

Germans are sometimes disappointed in American or British visitors with whom they find it difficult to have a really deep conversation. They find the constant moving from subject to subject superficial and careless. They find the urge to say things politely and not cause offense slippery. To their guests the Germans seem perfectionist, elitist, and determinedly, to use an expression coined by a German-speaking psychologist and philosopher, “anal.” There is a recipe here for cross-cultural misunderstanding, unless, of course, you understand where your colleague is coming from.

And here’s another cross-cultural problem. One of the reasons German children are taught to watch their language is that what they say represents their honor. The Germans set great store by doing what they say they will do according to the recognized rules and nothing more. The idea of exaggerating your qualifications or citing your successes in order to boost your profile to get a better job is unacceptable by German standards of honor and objectivity. “Keeping your options open” is not necessarily the honorable option for a German. This is a country where verbal agreements are morally binding. A German’s word quite literally is his, or her, bond.

Honorable behavior entails keeping your commitments. This is important in business communications. It is vital for foreign negotiators to be very clear about what has been agreed and what has not. It is not uncommon for deals to fail because what the Americans or British considered to be “thinking aloud” was taken by their German counterparts to be a commitment. The Germans can be unforgiving about what they see to be unreliability or lack of credibility. An example of the social confusion that can be caused is the American and British use of phrases such as “I’ll call you” or “We must have lunch” as expressions of goodwill. The Germans see them as a commitment, and are upset if they are not followed up.

Part of an honorable way of expressing yourself is to be as clear and as unambiguous as possible. One way of doing this is to strive for impersonal objectivity in your speech. There is even a term for this, Sachlichkeit, objectivity. You attain objectivity by the use of the pronoun “one” (man kann, one can), by the use of the passive voice, and, above all, by saying what you mean and meaning what you say. The Germans are wary of people who respond personally if their opinions are attacked, and they consider the idea of not upsetting the applecart, and “keeping things friendly,” as suspect. They also find the American “confessional” style of revealing personal information in the search for common ground astonishing and sometimes demeaning.

Lest you think that to be German is to be prosaic, boring, and preoccupied with minutiae, let us finish this discussion with a mention of Gemütlichkeit—a cosy or jolly atmosphere. The Germans in the right place at the right time, almost always out of the office, enjoy relaxed, leisurely conversation over a drink or food, which they describe as Unterhaltung, or simple conversation. This is much lighter than the analytical approach to discussion presented earlier. Taking place at home, in a Bierstube, or a restaurant, the conversation is light, and full of humor and companionship—another facet of the “serious” Germans.

Some social scientists claim that up to 80 percent of communication is nonverbal. They probably haven’t studied the Germans, who tend to be reserved and introverted, and who try not to draw attention to themselves. Facial expressions tend to be less demonstrative than those of the Americans and British, and smiles to be kept for family and close friends, although the Germans enjoy the smiling aspect of US life. Posture tends to be straight. German children are still taught to sit up straight, and “laid back” postures, although adopted by the young, are not well regarded.

The old joke that in Germany you shake hands with everything that moves, whenever it moves, really means that you should shake hands with everyone present both on meeting them and on leaving. Body language, then, in Germany is less expressive than in parts of the US, but similar to Britain, and visitors and negotiators should consider moderating their body language to what they observe around them. That being said, like every country, Germany has its peculiarities.

• The German equivalent to crossing fingers to wish for luck is to press your thumbs. If a German says, “I’ll press my thumbs for you,” it means “Good luck.” This may be accompanied by a fist with the thumb inside.

• Germans tap the side of their head with their index finger to indicate “You’re crazy!”

• A mistake that can cost you money is if you raise your index finger in a bar to order a beer – you may get two. Germans start counting with their thumbs, not their index finger.

• Most surprising, if you finish a presentation at a meeting, instead of applause you may be met with a rumbling noise as your German audience rap the table with their knuckles in appreciation.

• Children sometimes stick their thumbs between the first and second fingers of a fist to make a face. Stop them doing it in Germany: it’s an obscene gesture.

To communicate you have to make contact, and this is culturally defined, especially in business. Letters of introduction, or at least e-mails, followed by telephone calls are considered the right way to do things. Cold-calling, out of the blue, is not usually welcomed. Not so long ago there used to be a convention that faxes or e-mails would be followed up with hard copy in the post, but many Germans have now abandoned this practice. However, it is always worth checking on your colleague’s expectations. Job applications are normally typed, and a photograph is usually required.

The country code for Germany is 49 and there are area codes for each part of the country. The codes for the four main cities are:

Berlin (0) 30

Hamburg (0) 40

Frankfurt (0) 69

Munich (0) 89

Within the country dial 0 and the area code, and from overseas dial 49 and the area code without the 0. To dial out of Germany you usually dial 00 before the country code number.

For directory enquiries within Germany, dial 11833; for overseas directory enquiries, 11834. To find numbers online try world.192.com or http://www.dastelefonbuch.de/english.html. You can also use the phone book for residential numbers (Fernsprechbuch) or the Yellow Pages (Gelbe Seiten) at http://www.gelbeseiten.de/yp/quick.yp. Information appears in German but there is a Google translate bar to get the English version.

The telephone system in Germany is run by Telekom, which controls the network, and as in the USA and the UK there are alternative and possibly cheaper systems such as Arcor (dial 01070 before the number you want to reach), TelDelfax (01030), or Viatel (01079). You can choose a service by dialing the appropriate code before the number you are calling.

More and more people use cell phones and personal computers to communicate with each other, and ignore the public telephone system. However, international calls can be made through post offices. Go to the booth marked Auslandsgespräche (overseas calls). They can also be made with international calling cards or credit cards from public telephones. You will increasingly find Internet facilities available as well. Be careful about making calls from hotel bedrooms or restaurants. The surcharges are very high and your phone bill could well exceed your room bill.

When the Germans answer the telephone they normally just state their surname. You, too, should identify yourself and the standard German form is “Hier spricht Barry” (literally, “Here speaks Barry,” or “Barry speaking”). How do you ensure that people aren’t already asleep when you call at night? By not calling after 10:00 p.m., unless of course you know your respondent’s sleeping habits.

“Snail mail” is still important in Germany. You’ll see the yellow post boxes with the black post-horn symbol of the Deutsche Post all over Germany, and on mountain roads yellow vans will come hurtling past as they deliver parcels to mountain villages. Post offices open between 8:00 a.m. and 6:00 p.m., Mondays to Fridays, and between 8:00 a.m. and 12 noon on Saturdays. At stations and airports they may be open longer and even on Sundays. As you might expect, the German postal system is efficient, safe, and reliable, and next-day delivery is expected for letters posted at larger post offices before 9.00 a.m. There is usually one postal delivery a day. You can buy stamps either in the post office or from a machine outside (change is given in stamps), or at newsdealers.

Old post office in the spa town of Bad Liebenstein, Thuringia.

Post offices stock envelopes and parcel packaging. They also offer a range of other items and services to improve revenue. These include toys and collector’s items related to the post office, gift services for sending flowers and presents, lottery tickets, and concert and theater tickets. You can pay utility charges, keep a post office checking account, transfer money, and carry out various other functions associated with banks. The post office can also arrange mail collection services for you. To find out more about the German postal service contact www.deutschepost.de.

With a strong predominance of engineering graduates and the prominence of CEOs with Ph.D.s in engineering in many companies, Germany is one of the most “tech savvy” countries in Europe although small countries like Luxembourg, Switzerland, and Estonia are making faster strides toward creating “smart cities” and “smart governments.”

German youth, like the millennials in the US and UK, are obsessed with computer games and are avid users of IT and social media. They hang out on WhatsApp, Snapchat, and Instagram. TikTok is popular with Generation Z. When watching films or listening to music most German teenagers use streaming and media service providers such as Netflix and Spotify. Yet, even though German youth are technoholics, their values have shifted in comparison to Generation X. Security and stability come first, and it is reported that some are already starting a family in their twenties.

An experienced observer of European culture once said, “If you see something that surprises you, angers you, or that you find completely ridiculous, you may be in the presence of a cultural characteristic.” He also said that the people who display the greatest cultural differences may be the ones who look most like you. For the majority of Caucasian Americans, Britons, and northern Europeans, the Germans do “look like us,” and we should be careful not to assume that just because they “talk the talk,” they necessarily “walk the walk.” If you are upset by something said or done, take a breath and do not react immediately. If you were to ask people why they have behaved or said things in a particular way, nine times out of ten the explanation would be completely innocuous. A lot of cultural-awareness building consists of not allowing unfamiliar attitudes to throw you. Observing, hearing, feeling, and then talking, is the way to build and enjoy good relations with the people of this culturally rich, creative, and dynamic country.