Six

BEND ZE KNEEZ: ARLBERG INSTRUCTION

“Let’s not permit international bickering and national jealousies to thrive on anything so splendid as skiing. Let’s ski for fun, and learn what we can from our cousins across the water, so long as they don’t make the learning process a chore.”

—Lowell Thomas, 1937.

Otto Schniebs from Germany taught the AMC to snowplow in the 1928–29 season. “His unusual skill as an instructor, made the more effective by his engaging personality, and the brilliance of his own example have brought scores of learners to . . . the supple crouch, with its elastic knee, and the easy rhythmical Christiania.” (AMC Report, 1929.)

Peckett’s, on Sugar Hill, New Hampshire, is considered the place where American ski schools got their start in 1929. Every morning, the instructors—they were called trainers to begin with—began with twenty to thirty minutes of calisthenics on skis, before launching into the Arlberg technique.

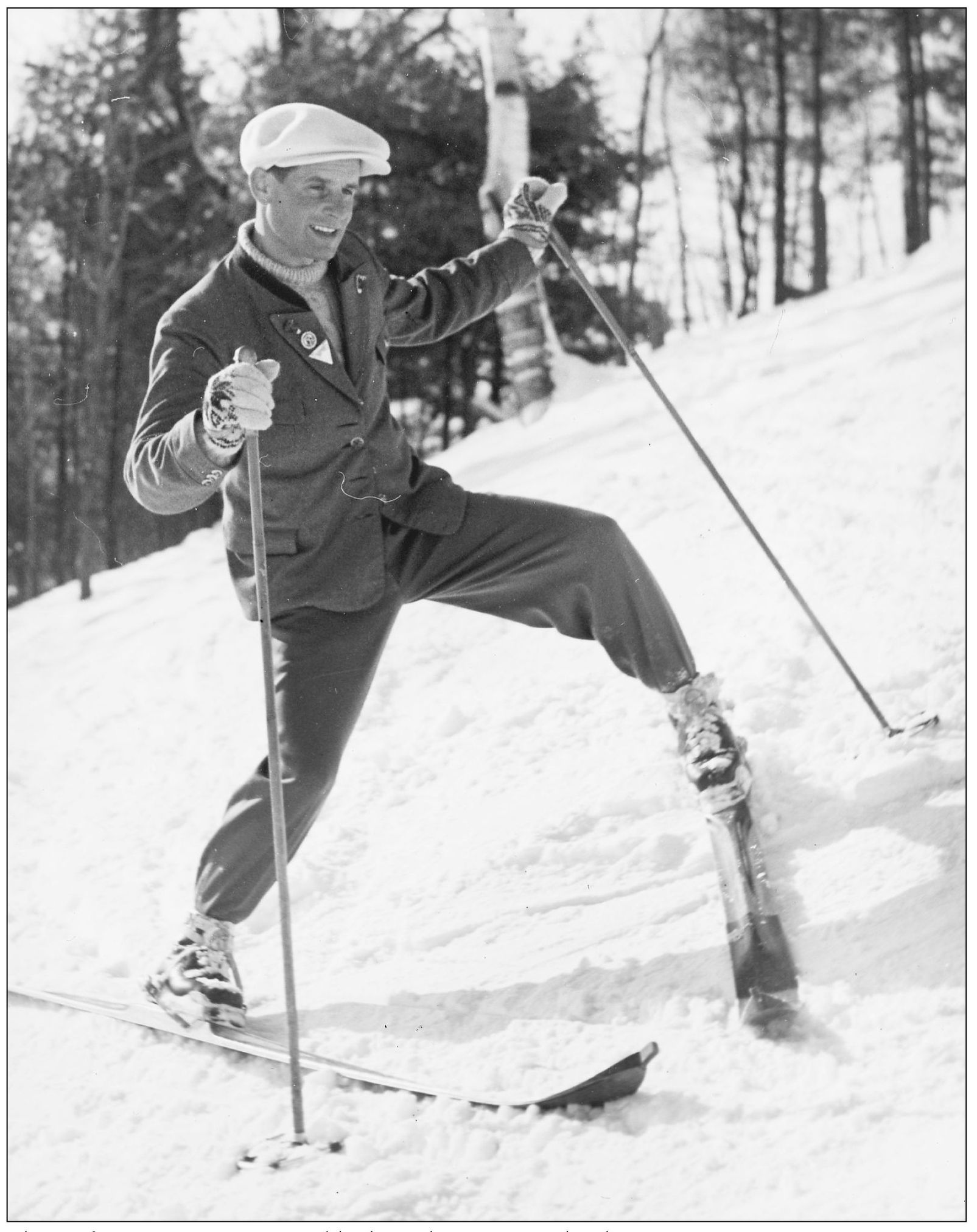

A long line of European instructors taught skiing all over New England. Here Florian Haemmerle, suitably eccentric, “bends ze kneez” for the Hanover Inn.

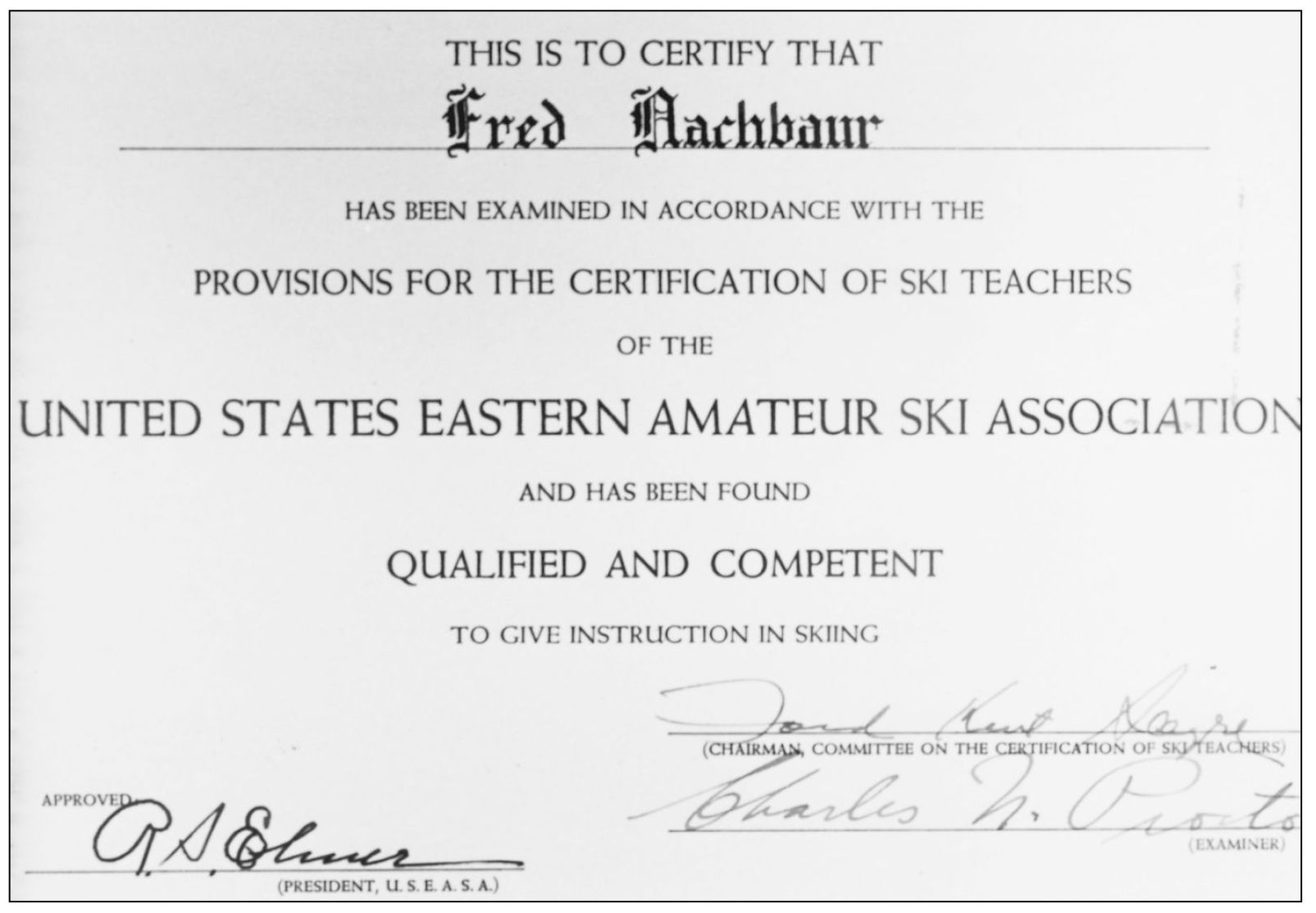

After four years of discussion, the United States Eastern Amateur Ski Association held its first examination for professional instructors on February 14, 1938, at Woodstock, Vermont. Seven men passed. By the 1939–40 season, three women had become certified.

Fred Nachbaur, American-born but fluent in German, was once refused a ski instructor’s job because he did not have enough of an accent! Nachbaur became a major influence on skiing in the Gilford, New Hampshire area.

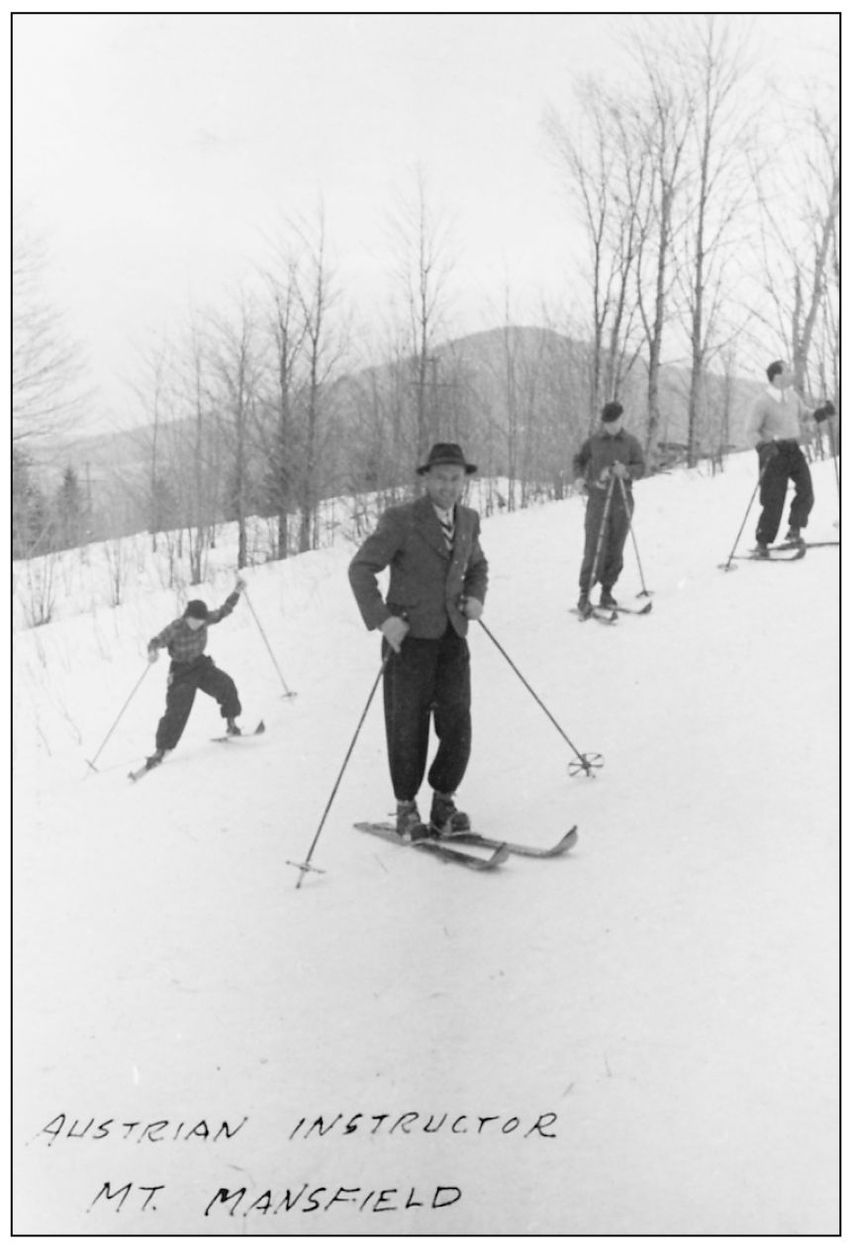

“The Austrian Instructor” arrived in Stowe, Vermont, in 1936, and immediately advocated cutting down more trees for open slope skiing. Sepp Ruschp remained in Stowe until his death in 1990.

Sepp Ruschp taught the Arlberg technique in his Arlberg outfit, including the Tyrolean hat. Vermont ski centers were slow off the mark to develop, partially because the state’s attorney general had said in 1937 that paid admission for skiing was against the law on Sundays. A state of Vermont assessment for the 1937–38 season concluded that it was still questionable whether skiing was going to be a permanent factor in the state.

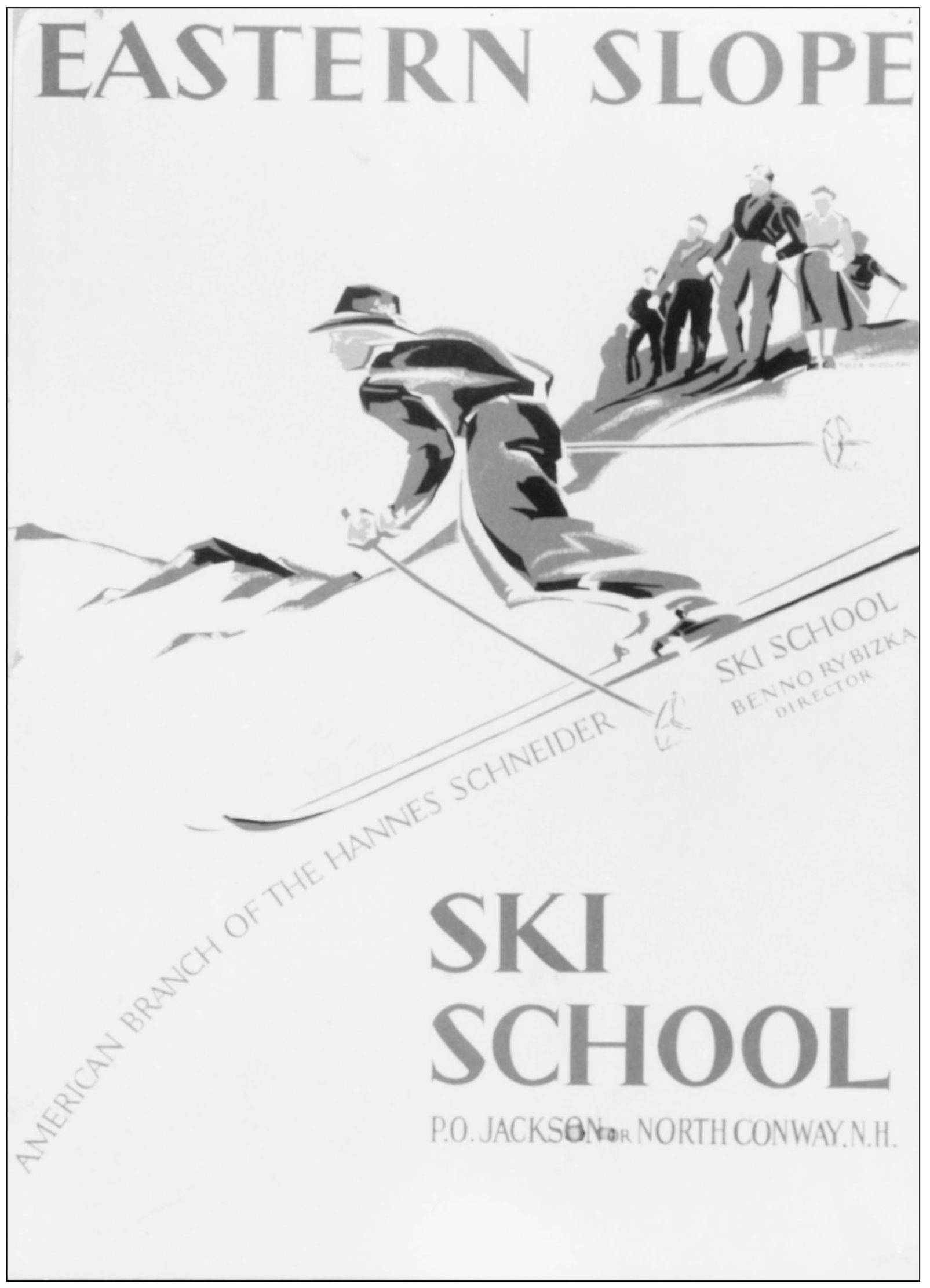

The Arlberg teaching and technique became entrenched in New England, with Benno Rybizka as guardian of the American branch. According to one of his instructors, he ran the ski school like a Prussian general. But the clients kept coming. Ski school was almost a requirement for the beginner.

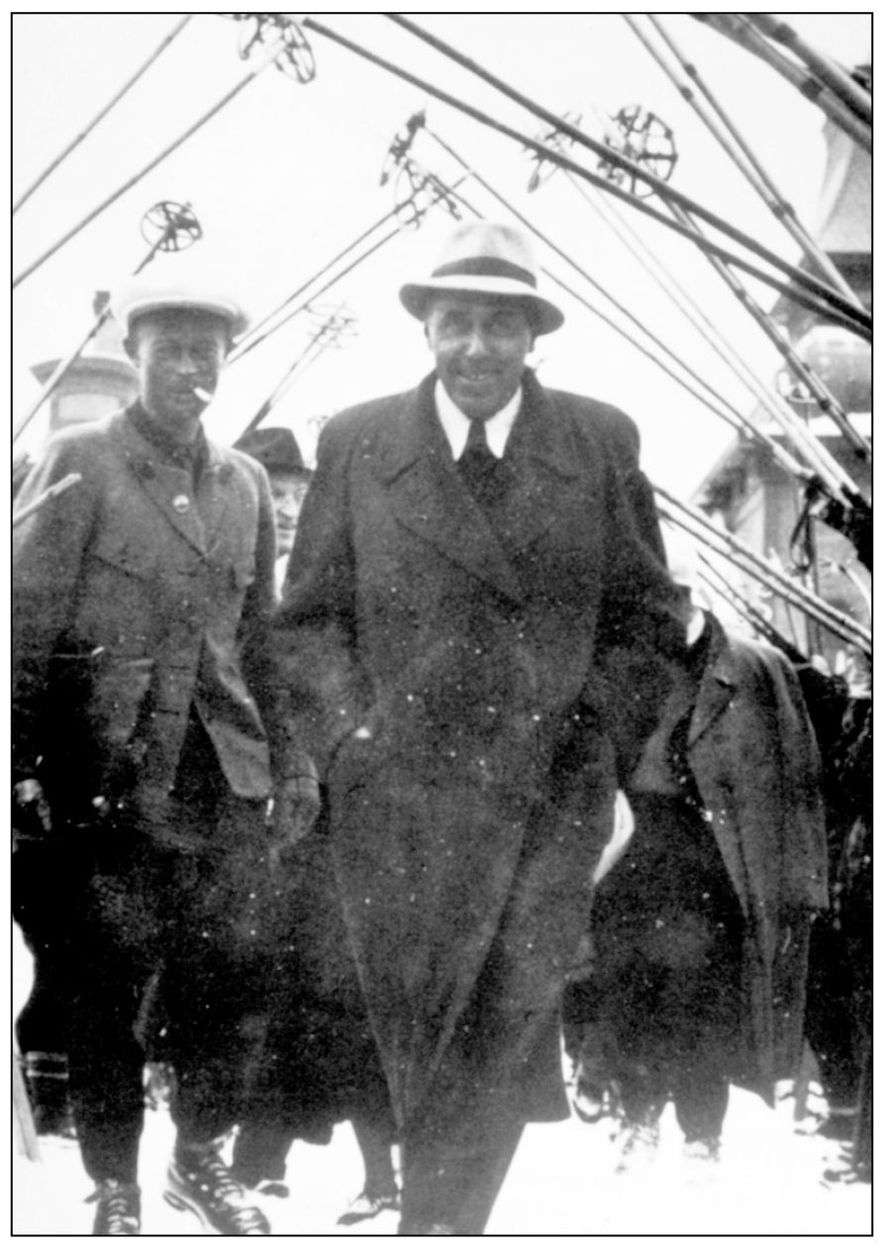

Hannes Schneider (right), with Benno Rybizka at his side, arrived in North Conway in 1939. He had been under house arrest in Germany because he had supported a Jewish member of the Austrian Ski Association. Harvey Gibson’s money—he was president of the Hanover Trust—and pressure from Arnold Lunn, co-founder with Schneider of the Arlberg-Kandahar race, finally extricated him from the Nazis. He made his home in North Conway until he died in 1955.

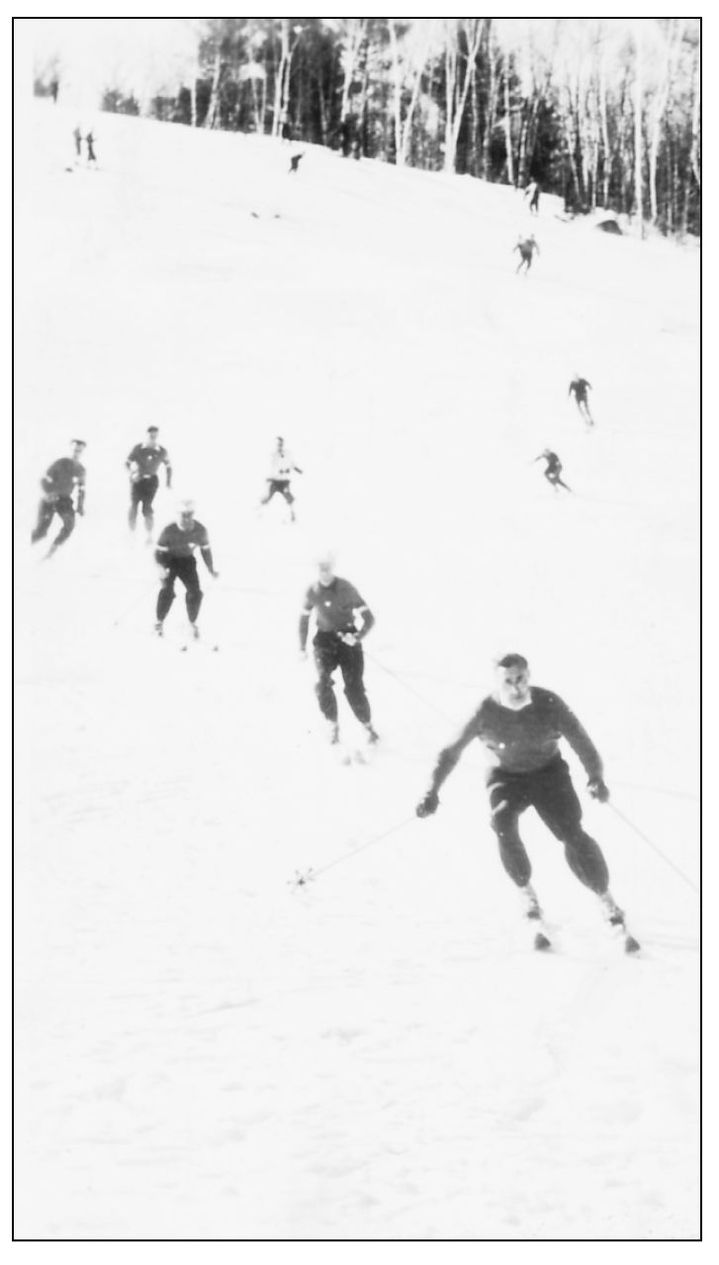

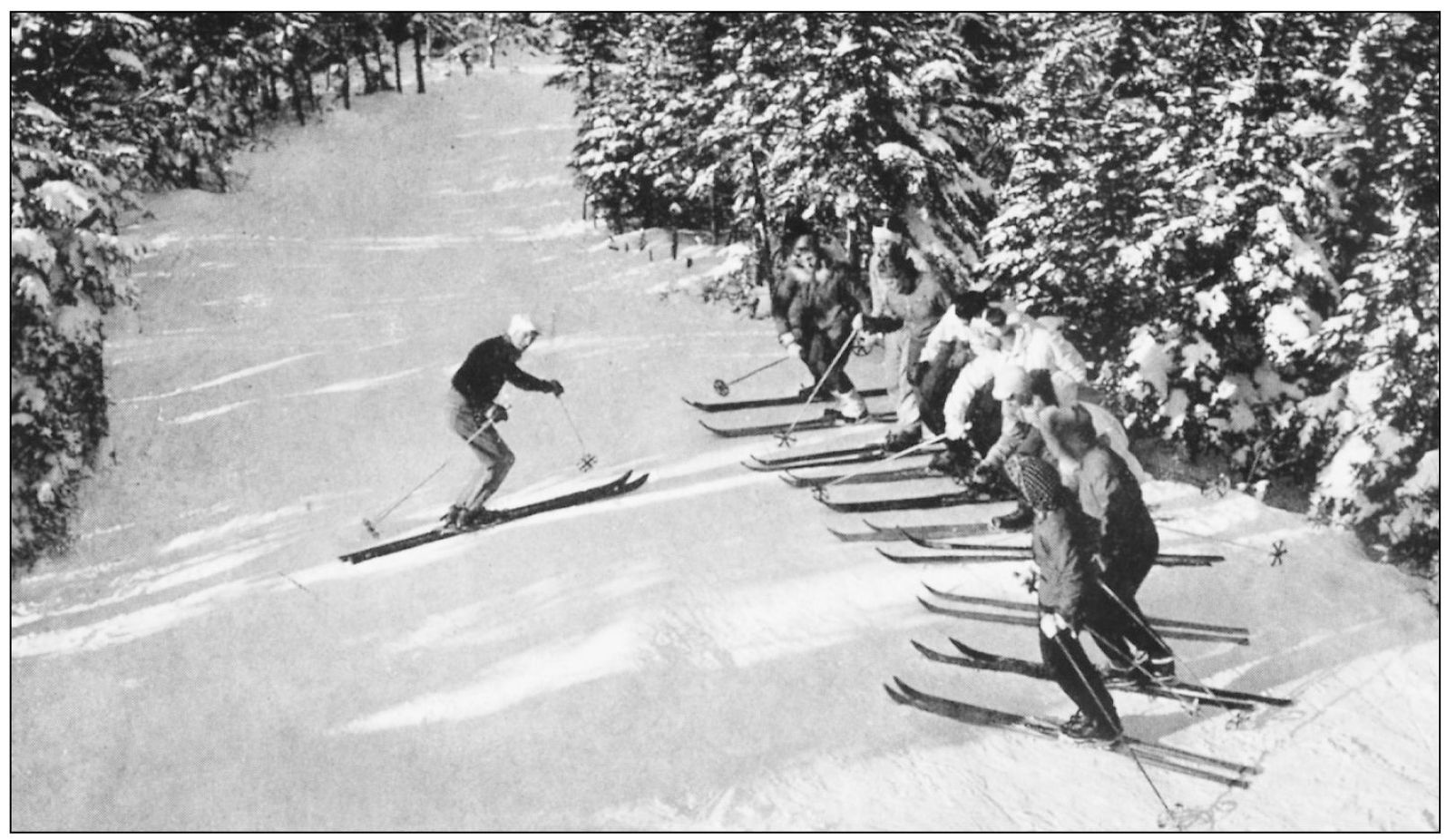

Hannes Schneider is seen leading his instructors down the open slope at Mt. Cranmore, New Hampshire.

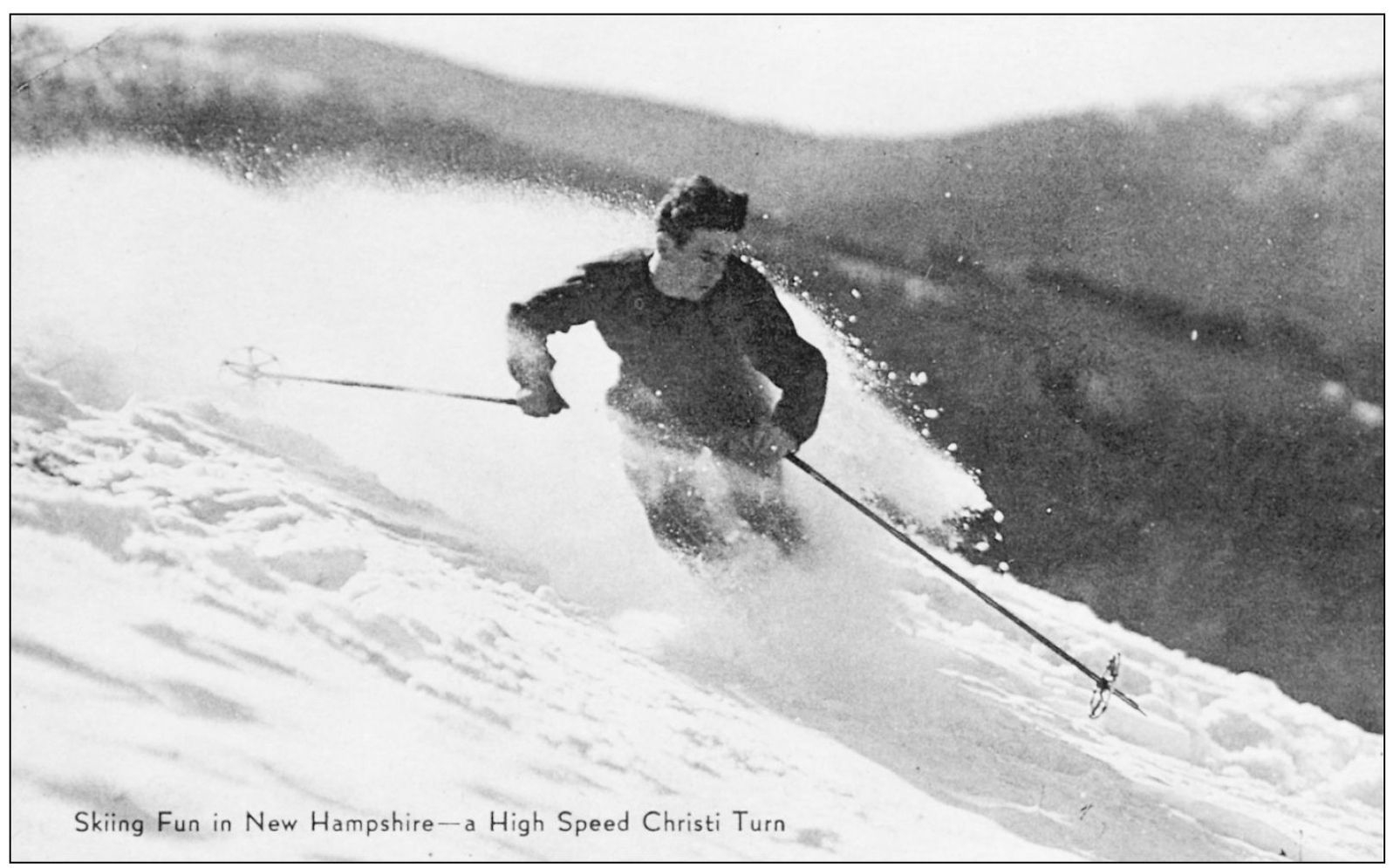

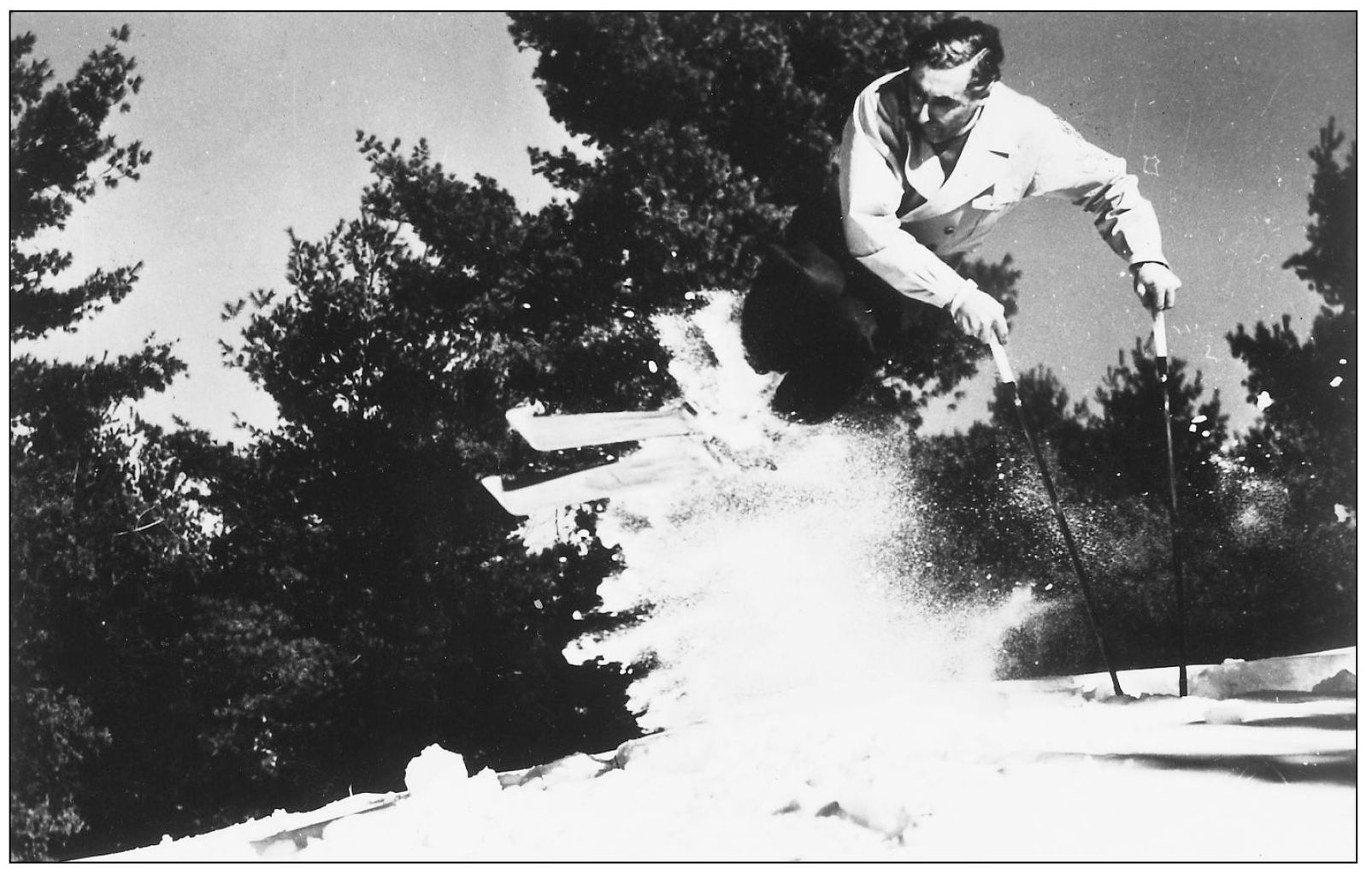

On the back of this postcard was written, “I actually saw him doing this!!” Instructors were the stars of 1930s skiing, and it was essential that periodically they show off their skills.

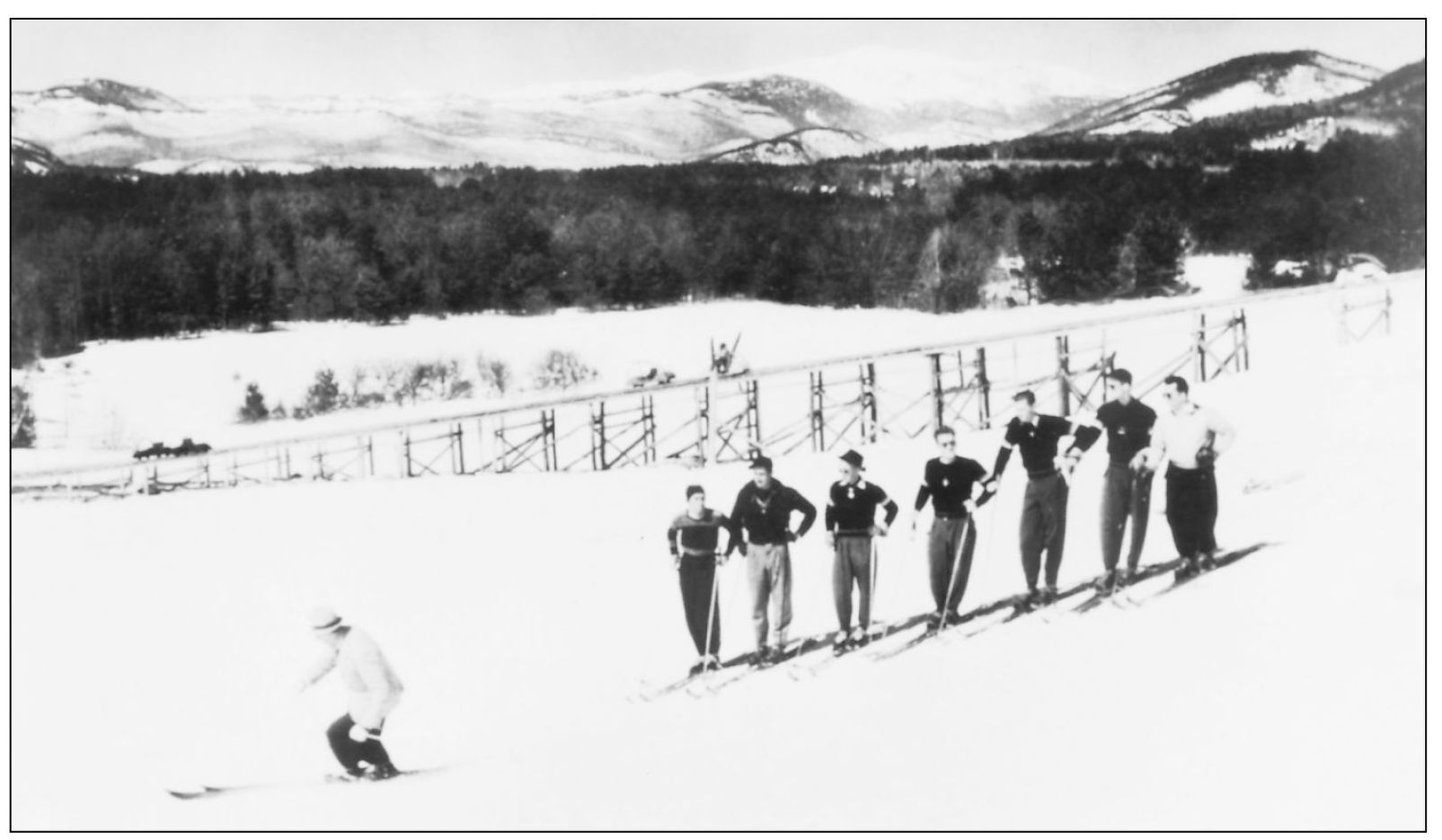

Here, the Skimeister instructs the instructors, although a couple do not seem to be paying much attention! Mt. Cranmore’s skimobile is in the background.

One necessity for all beginners was to learn how to herringbone up a hill. The skier on the left is sidestepping.

To raise the standard of club skiing, Otto Schniebs gave a course for club instructors (i.e., nonprofessionals) in 1938. This group is a who’s who of New England skiing. Among them are: (far left) Park Carpenter, AMC and snow train organizer; (seventh from left) H.H. Whitney, owner of a ski lodge and center in Jackson, New Hampshire, and inventor of the “shovel handle lift”; (ninth from left) J.W. McCrillis, co-author, with Otto Schniebs (third from right) of one of the most popular instructional books.

Otto Schniebs, coach at Dartmouth from 1931 to 1936, seemed to electrify the Hanover community with the new Arlberg technique. One erring student once executed a perfect Norwegian telemark turn. “Don’t ever let me see you make that turn again,” admonished Otto, “dot is a lady’s turn.” His fractured English became part of the Schniebs lore. When asked what to do if conditions were awful, he replied, “Vell, either take the damned skis off and valk—or schtem—schtem like hell!”

In typical organized, even military line-up, a Cannon Mountain class watched Hans Thorner’s demonstration of the pole plant.

Here, Sepp Ruschp leads his “Hot Four.” From left to right are Kerr Sparks, Howard Moody, Lionel Hayes, and Otto Hollaus. Compare this photograph with the first pictures of “the Austrian Instructor” on p. 70. By 1940, Sepp had his ski school, its students, distinctive in their sweaters and caps, organized along modern, American lines, yet looking European.

Hans Thorner from Switzerland, among the seven who were first certified as instructors in the United States, parlayed his expertise into this advertisement for Camel cigarettes in the late 1930s.

The perfect instructor, impeccably dressed, Franz Koessler demonstrates a stem turn in 1938.