CHAPTER THREE

Introduction to Egg Quality

High-quality food is the desire of consumers worldwide, and purchasers of eggs are no different. Whether eggs are purchased from a local producer with 50 free-range hens or from retailers selling eggs from major egg producers with hundreds of thousands of hens, high quality is still paramount.

The quality measure of eggs, unlike many other commodities, has little to do with wholesomeness or nutritional value and everything to do with appearance. Other measures—including shell or yolk color and egg size—while not technically related to quality measurements, are also important to consumers.

Each commodity has developed grading or quality nomenclature that is often specific to that commodity and not directly transferable. Quality grades, such as “Fancy” or “Extra Fancy,” “Choice” or “Prime,” and “Virgin” or “Extra Virgin,” give consumers a general idea whether quality is high, medium, or low. Quality in eggs is based on their visual appeal, both at the level of the shell and the internal contents.

Before discussing egg quality, it must be noted that eggs are graded based on the lowest grade characteristic—the various grade components are not additive when determining overall grade. In other words, an egg with a high-grade shell and low-grade internal contents has an overall low grade, and an egg with several medium-grade traits of both shell and contents remains as a medium grade.

Egg-Quality Grading

Eggshells, which are not generally consumed, provide a single-serving natural packaging of eggs that makes food scientists green with envy. Most eggshells are of high quality as they are laid by the hen, but there are still several shell criteria used in grading.

SHELL SHAPE

Normal, high-quality eggshells are an ovoid shape, or a three-dimensional oval. This ovoid shape has only one axis of symmetry, the long axis, so when held vertically, the right and left sides are essentially the same shape. However, when examining the top and bottom halves of the ovoid, one is broad (blunt) while the other is narrow (pointed). High-quality eggs should have this shape. Lower-quality eggs have any shape other than this defined ovoid. Some eggs will be round, while others will be narrow and long, resembling a torpedo.

Other misshapen eggs include those with a wrinkled appearance, resembling a prune. During egg formation, following the addition of the shell membranes, the contents are typically “plumped” with metabolic water, which serves to distend the membrane to provide a smooth surface as a base for the shell. Sometimes the plumping is incomplete, so that when the shell is deposited, the membranes are somewhat flaccid and wrinkled. The shell simply takes on the shape of the membranes beneath with the typical characteristics of a hard shell.

The surface of an eggshell is covered with pores that are necessary for gas exchange and water loss during chick embryo development. These pores are also responsible for the water and carbon dioxide exchange of table eggs that contribute to the eventual loss of quality over time.

Body-checked eggs are those that have the appearance of a bulge or “belt” around the middle of the egg, about halfway between the blunt and pointed ends. This occurs when the eggshell cracks in the oviduct of the hen before its formation is complete. Extra shell is deposited over the break to repair the damage, which is similar to how your own body repairs a broken bone. This region of thicker shell material gives the characteristic bulge of the body check.

Occasionally, two eggs end up in the oviduct at the same time. When this occurs, both eggs take on the characteristic shape of a slab-sided egg, or one with a flat side. Where the two eggs touch during shell formation, one side is flattened as the shell is deposited. The flattened side is often markedly thinner than rest of the shell, making it much weaker.

It is worth noting here that some diseases—often respiratory viruses—can cause misshapen eggs. Infectious bronchitis, Newcastle disease, and egg drop syndrome (not found in North America) are some of the important diseases in this group. In addition to the problems that they cause in eggs, clinical signs of respiratory disease will also be present, including noisy breathing (rales); coughing; drainage from the nares (nostrils), mouth, or eyes; and possibly a swollen face. These diseases are rare in small flocks of chickens, where most misshapen eggs are the result of other causes.

SHELL TEXTURE

High-quality eggshells should be relatively smooth to the touch. Shells with a rough, sandpaper-like feel to them are indicative of lower grades. In general, young hens produce smooth-shelled eggs, but as they reach 12 to 18 months in age, the shells of their eggs begin to have that sandpaper feel. Following the molt, the natural loss of feathers that usually occurs in the fall each year, shell texture improves again, losing some of the roughness. As post-molt production continues, the roughness of the shell increases more quickly and more severely, becoming quite obvious in the hen’s second year.

Occasionally, eggs are produced with a sizable “blob” of extra calcium deposited in one or a few locations on the surface of the shell. These deposits can be from a few millimeters across to half an inch (1 cm) or more in size. Some have described the appearance as similar to a small amount of toothpaste squeezed onto the egg’s surface. Determining whether a deposit constitutes a downgrade is somewhat subjective. If the consumer were to attempt to remove the deposit and this resulted in a hole in the shell, that egg would be considered poor in quality.

Why are shells sometimes rough?

The roughness is a consequence of the hen’s reduced ability to form shells properly. Sometimes, increasing calcium in the diet can slow this process, but in the long run it is inevitable in most hens that lay into their third, fourth, and fifth years of life.

Normal

Calcium deposits

Clean shells are often the most obvious quality issue with eggs. Management of the hens, including regular cleaning of nests and coops, and hens “trained” to lay in nestboxes, is the best way to reduce the incidence of dirty or stained eggs.

Dirty eggs are those that have material adhering to them. This material can be litter from the nest, soil from the chicken yard, blood (generally from a small hen laying a large egg), or feces from the nest or feet of the hens. Typically, dirty eggs can be cleaned to remove this material, either by dry cleaning with a bit of sandpaper or by washing. (Note that care must be taken when washing eggs, as use of detergents, water temperature, time spent washing, and disinfection all can have negative consequences if done improperly.)

If, after cleaning, stains remain on the shell, they may or may not affect the quality depending on their size and prominence. The more visible the stain, the greater the possibility that the egg would be considered lower quality.

It should be quite apparent that when eggshell quality is considered, appearance of the egg is paramount. Consumers want to see eggs that look appealing. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), which regulates egg quality in the US, uses the phrase “practically normal” when referring to high-quality eggshell. Admittedly, “practically normal” is a subjective determination and is greatly dependent on the eye of the beholder.

Protection during processing, packaging, and transport are also of great importance to shell quality. Eggs with odd shapes and textures don’t fit in the cartons properly, rendering them more likely to be cracked or completely broken between lay and consumer sales.

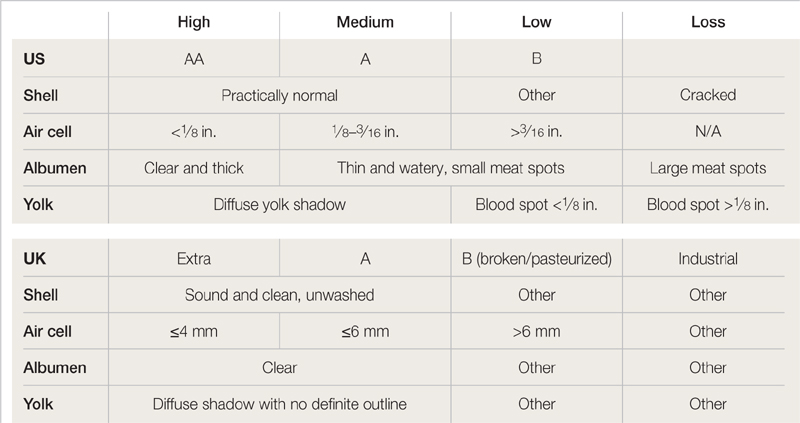

In the US, external egg quality grades are quite simple. Based on all of the quality issues noted above—shape, texture, and cleanliness—eggs receive a grade of either “AA” or “A” if their shells are “practically normal” and clean, or “B” if they have any shape or texture issues and only slight or moderate staining. Any egg that has material adhering to it is graded as “Dirty” and cannot be used for human consumption. The system is quite simple and somewhat easy to follow.

In the UK, the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) has a similarly straightforward system of egg-quality classification. Eggs with “normal, clean, undamaged” shells are Class A; those with “normal, undamaged” shells are Class B; and those that are “cracked, misshapen, rough textured” or have “any other abnormality” are Class C. Eggs that don’t reach Class C standards are classed as “Industrial Eggs” and are unfit for human consumption.

CRACKS

For all graded eggs, whether of high or low quality, the shells must be unbroken (sound). A cracked shell represents a major loss to the producer but a few of these eggs can be salvaged for use as human food by further processing. However, it must be noted that once the shell is cracked, the potential of contamination by pathogenic bacteria is exponentially increased, thereby increasing the possibility of foodborne illness. Cracked eggs from small flocks of chickens should be discarded.

Cracks are classed in two categories: the shell is cracked but the shell membranes remain intact and the contents are not leaking; or both the shell and membranes are broken and the contents are leaking.

Non-leaking cracks in commercially produced eggs, sometimes called “checks,” are only used as a pasteurized liquid egg product. In general, along with many downgraded eggs with sound shells, these eggs are broken by machine and the contents (yolk and white) are separated and pasteurized. They are then sold in either large or small containers directly to consumers or to large egg users such as bakeries.

Leaking cracks are condemned and often processed into either animal feed or non-food industrial products.

The quality of the interior of an egg is based on a visual examination during candling, a method of shining a bright light through an egg to observe its contents (see here). While the shell is solid, it is generally thin enough for light to penetrate sufficiently to determine enough information to assess the quality of its contents. White-shelled eggs are much easier to candle, whereas the contents of brown-shelled eggs are more difficult to see, especially if the light is dim and the room is light.

AIR CELL

The air cell of an egg typically forms at the blunt end after the egg is laid. During the egg’s formation, its contents completely fill the interior. After it is laid, the egg begins to cool from the normal 106.5˚F (41.4˚C) deep body temperature of the hen to room temperature. While it is cooling, the contents contract within the ridged shell, which itself remains the same size. Because of the porous nature of the shell and the fact that there is a higher concentration of pores at the blunt end, the shrinkage causes a small space to form—the air cell. This air cell forms between the inner and outer shell membranes; biologically, it is used by the chick to take its first breath before hatching, but when considering table eggs, it is an indicator of quality.

Candling

When candling, there are three relatively obvious traits that can be seen which will indicate the quality of the egg: the air cell, the yolk, and the albumen. Each has visible attributes that can easily be observed to determine whether the egg is high or low quality.

The air cell increases in size as water is lost through pores in the shell. Smaller air cells are indicative of higher egg quality.

Immediately upon laying, the porous egg begins to lose water in the form of vapor. This water loss is fairly constant, as it is simple diffusion across the membranes and shell of the egg. As moisture is lost, air continually diffuses into the egg, taking up the space left by the lost water, and the air cell enlarges. In general, most eggs with high-quality shells will retain a small air cell for 30–45 days if stored properly. As the egg ages, the air cell continues to enlarge.

High-quality eggs have small air cells. In the US, the highest-grade eggs (Grade AA) must have an air cell that is no larger than ⅛ in. (3.2mm) when measured from the top of the blunt end. Medium-quality eggs (Grade A) have an air cell that is ⅛–3/16 in. (3.2–4.8 mm) deep. Any eggs with an air-cell depth greater than 3/16 in. (4.8 mm) are considered poor quality (Grade B).

Similarly, in the UK eggs with an air cell less than ¼ in. (6 mm) deep are graded as Class A, and those with less than 3/16 in. (4 mm) deep as “Extra Fresh.” Those with an air-cell depth less than ⅜ in. (9 mm) are Class B, and those with a depth greater than this are Class C.

Testing for egg freshness

The size of the air cell and hence the freshness of an egg can also be determined by floating it in a bowl of water. If it floats it has a large air cell and tends to be old (it will have lost a considerable amount of water vapor, yielding a large air cell), while if it sinks it has a small air cell and is fresher. While shell thickness can play a role as to whether an egg will float or sink, this is a quick way to determine freshness.

Occasionally, the air cell will be misplaced so that it doesn’t remain at the blunt end and instead floats around, or it may appear bubbly. Quality in these cases is estimated based on its size only, not on whether it is fixed or bubbly.

Upon candling, the albumen is observed for clarity and firmness. High-quality eggs have clear, firm (thick) albumen. During candling, the egg is rotated so that movement can be observed. Slow, viscous movement of the albumen indicates a high-quality egg, while more fluid, water-like movement indicates a poor-quality egg.

For many, it seems counterintuitive that the water loss causing the air cell to increase in size would also cause the albumen to become watery. To explain this phenomenon, a bit of chemistry is necessary.

At the same time as water is lost from the egg and the air cell increases in size, carbon dioxide that was dissolved in the albumen during egg formation is also lost from the egg. As the carbon dioxide diffuses from the egg, the pH of the albumen increases from a relatively neutral pH of about 7.5 to an alkaline pH greater than 9.0. Albumen is composed mostly of water (about 85 percent) and protein (about 12 percent). Each of the 13 different proteins that make up the albumen has a particular physical shape that is highly dependent on pH. As the pH increases, moving from neutral to alkaline, the protein structures change, reducing some of the tight bonds so that they become more flaccid, and hence the albumen becomes thin and watery.

Candling also allows any particulates in the albumen to be seen as shadows. Small pieces of ovary that break off during ovulation may end up in the albumen; these are called “meat spots.” Small meat spots reduce the quality of an egg to a poor grade (Grade B in the US, and Class C in the UK), while those that are large and obvious reduce the quality to the point where the egg cannot be sold for human consumption.

YOLK

Observations of the yolk are dependent on the albumen. When the albumen is thick and firm, the yolk is held down in the middle of the egg, some distance from the shell. When the egg is candled, such a yolk appears as a dispersed shadow, more like a yellow or orange color distributed throughout the egg. As the albumen thins over time, the yolk will float closer to the shell, giving a more prominent shadow almost to the point that its outline can be visualized. The yolk is little affected by the process—only its appearance changes.

Blood spots on a yolk always result in the egg being graded as poor quality. These spots of blood are often wrongly considered as an indication of fertility. In reality, blood spots occur during ovulation. Occasionally, when the ovarian follicle opens to release the yolk, a small amount of bleeding occurs onto the surface of the yolk and is retained during the formation of the egg. Small blood spots (less than ⅛ in. or 3 mm) downgrade eggs to poor quality (Grade B in the US, and Class C in the UK), while anything bigger will render the egg unsuitable for human consumption.

Determining the shell quality and thickness

Gravity on eggs

The specific gravity of eggs is one measure used to determine shell quality, or more precisely, shell thickness. Eggs are placed in various concentrations of salt solution, usually between 1.070 and 1.085 specific gravity. Eggs that sink at the higher densities have thicker shells and are of higher quality.

INTERNAL QUALITY BY BREAKOUT SAMPLING

As part of the regulation process in commercial egg production and in research, more accurate objective measurements of egg quality are often desirable. All of the previous determinations are quite subjective, relying on individual observers to provide a determination of quality, each of whom may have different requirements for grading. Objective measurements, however, give a more precise picture of quality.

Floating eggs in water can indicate their freshness (based on the size of the air cell). Eggs that sink in water have small air cells, which indicates freshness, while those that float have large air cells and should not be consumed.

Other objective measurements require breaking the egg, so only a small representative sample is used. Breaking the egg on a flat, level surface—often a piece of glass—provides the best way to observe and measure egg contents.

First, the shell’s thickness can be measured directly following breakout. Usually several measurements are taken at the blunt end, middle, and pointed end of the shell, and the average is then taken. Normal chicken eggshell thickness is between 1/32 in. (0.7 mm) and 1/16 in. (1.5 mm).

The primary objective measurement of quality, however, is the thickness of the albumen. Using this and the overall weight of the egg, the Haugh unit of the egg is calculated, which is considered the most accurate measurement to determine egg quality.

Other observations include the overall appearance of the broken egg, such as whether the albumen spread is small or spread out, and whether the yolk stands tall or is flattened and may sometimes break. Both of these are dependent on the thickness of the albumen. Finally, any blood spots are noted during breakout observations.

The proper method of storing table eggs, from hen to consumer and beyond, is a controversial subject with public health professionals, producers, and consumers. Discussions concerning vaccinations of layers, washing of eggs, and refrigeration after packing have resulted in different requirements between countries. Some suggest that eggs can be stored at room temperature without any special packaging or temperature control, while others stipulate that refrigeration is absolutely necessary for food safety and to maintain quality. Washing and sanitizing eggs prior to packing to reduce the bacterial load on their surface is required by some and forbidden by others. Some countries vaccinate hens specifically to reduce colonization by Salmonella bacteria in the gut and ovary, while others have outlawed the practice.

In the early 1990s, following an outbreak of foodborne illness caused by Salmonella enteritidis contamination in the eastern US, eggs took on the status of a perishable food product, henceforth requiring refrigeration within hours of lay and throughout the market stream to the consumer. Labels on egg cartons strongly suggest that consumers also refrigerate eggs in the home. The cold temperatures found in fridges are known to slow the reproductive ability of bacteria, so if any food—including eggs—is contaminated, the number of bacteria remains few enough that the possibility of foodborne illness is greatly reduced.

In addition, there has also been a requirement in the US for many years that eggs are washed and sanitized under strict temperature and chemical controls to reduce the bacterial load. Producers of more than 3,000 hens are also required to test their environments for Salmonella enteritidis, with strict protocols of egg usage and subsequent cleaning put in place of bacterial contamination is found. More recently, vaccines have been voluntarily used by most large egg producers to reduce the incidence of S. enteritidis.

Egg safety has taken a completely different track in the UK, where neither washing nor refrigeration are allowed prior to sales of Class A eggs. Washing eggs removes their protective cuticle, which is known to reduce contamination of egg contents by surface bacteria, so in effect nature’s defense against contamination is employed. Removing eggs from the cold temperatures in a fridge often results in water condensing on their surface, thereby increasing the possibility of contamination, which is why refrigeration is not recommended here either. Vaccination of hens for S. enteritidis is virtually required in the UK by most producers with some exceptions, and this has been quite effective in reducing foodborne illness caused by the bacterium in the UK.

Salmonella bacteria

An intact egg shell does not guarantee that it is free from bacteria because they can pass through the shell pores.

So, the debate continues; there is no consensus on the proper way to store eggs. Eggs will keep and maintain their quality longer when refrigerated, but if used quickly—within a week or so—the taste and baking characteristics of eggs at room temperature are better. Each producer and consumer should follow the laws and suggestions by their respective regulators. And as the final measure of food safety, consumers of eggs should cook them thoroughly prior to consumption.