From the fifteenth century until the eighteenth century, witch trials were conducted across England. They resulted in the death of between 500 and 1000 people, 90 per cent of whom were women. Suspicion and accusations of witchcraft were at the most intense stage during the Civil War and the Puritan era of the mid-seventeenth century.

Between 1484 and 1750, women were tortured, burned or hanged, often condemned by the most fragile thread of evidence, baseless allegations that led to them being harassed, accused, tortured and put to death.

Older women from poor backgrounds were often suspected, especially if they had a sign or feature that set them apart: if they were snaggle-toothed, if they had a hairy lip, a pointed chin, warts. Even more so if they were seen to possess a familiar – a cat or a dog being most common.

Younger women were also at risk. People were suspicious if a married woman had too many children, or too few: this set her apart from the others. A woman with skills in healing, or one who was deemed to exhibit ‘strange’ behaviour, was immediately under suspicion, as was a woman having a birthmark or a mole.

In Somerset, during the period of 1573–1600, 1 per cent of people had their deaths recorded as ‘death by blasting’ or bewitchment. In the mid-seventeenth century, Edmund Bull and Julian Cox were hanged as witches. Elizabeth Stile was also accused; she died in Taunton jail in 1664. Jane Brooks and Alice Coward from Shepton Mallet were accused of casting spells on a twelve-year-old boy.

In 1887, as workers pulled down an old house of thick cob walls in Wellington, Somerset, they found in a space which separated the roof from the upper room six brooms, an old armchair and a rope with feathers. The workmen believed that these articles were the belongings of a witch, and that the rope was a witch's ladder.

There are some fascinating, evocative place names across Somerset, from Witches Walk in Bridgwater to Stonegallows in Taunton.

The last execution for witchcraft in England was in 1684, when Alice Molland was hanged in Exeter, Devon, although no documentary evidence of her actual execution has been found. Witchcraft was punishable by death during the times of the Tudors and Stuarts. After 1736, ‘witches’ could no longer be hanged, but it was by no means the end of their persecution. They were perceived to have close associations with the Devil, believed to be his helpers on earth. Ignorance and fear led people to believe that any bad occurrence was the work of the Devil or witches. King James I wrote a book on witchcraft, suggesting various ways of identifying and catching witches.

Against this background, I created the story of Grace Cotter. The village in which she lives, Ashcomb, later Ashcombe, is a composite of Somerset villages around the Blackdown Hills, near Taunton. While Grace is a character of my imagination, she and the people she interacted with in 1682/83 represent the rural farmworkers of Somerset whose lives were deeply affected by superstition and a strong belief in the supernatural. Grace’s story begins in the early spring of 1682, ten years before the infamous Salem witch trials in Massachusetts.

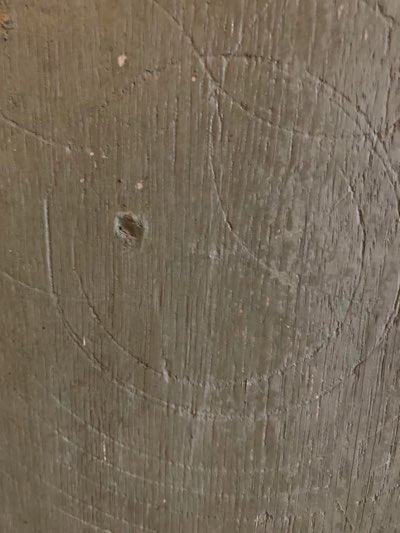

During my research for this novel, having seen examples of ‘witch’s marks’ online, I discovered similar markings, a hexafoil, on a wall of my own cottage in the oldest part of the house.