AT midday on 17 June, the day after Reynaud’s resignation, Pétain made his first radio speech as Prime Minister:

At the request of the President of the Republic, I assume the leadership of the government of France starting today. Certain of the affection of our admirable army, which has fought with a heroism worthy of its long military traditions against an enemy superior in numbers and in arms. Certain that it has through its magnificent resistance fulfilled our duties towards our allies; certain of the support of the war veterans whom I had the honour to command; certain of the confidence of the entire French people.… It is with a heavy heart that I say to you today that it is necessary to cease fighting. I have this evening approached the enemy to ask if he is ready to try to find, between soldiers, with the struggle over and in honour, the means to put an end to the hostilities.1

When this speech was printed in the papers the next day, the words ‘cease fighting’ were changed to ‘try to cease fighting’. Since an armistice had not yet been signed, to order soldiers to stop fighting already would have destroyed the last shreds of bargaining power left to the French government. Even so, few who heard Pétain’s broadcast can have had any doubts that the battle was over.

There is a famous French film of the autumn of 1940 depicting a village community gathered around the radio to hear Pétain’s speech. The reality was very different. As the German wave crashed over France, the French people, whether soldiers in retreat or civilian refugees, found themselves washed up all over the country. Lieutenant Georges Friedmann, in civilian life a philosopher, found himself in Niort; south of the Loire:

At half past midday, during lunch, Pétain announces the cessation of hostilities. The overture of negotiations for an armistice. I was expecting it. But still it is a terrible shock. That idiot L. can’t resist throwing in his opinion: ‘the politicians have fled the ships like rats.’ But the others say nothing, devastated. Ten men remain together silently face to face, and once the meal is over they get up without having said a word.

A few days later Friedmann reflected on the deeper meaning of what he had witnessed over the last six weeks:

A whole country seems suddenly to have given itself up. Everything has collapsed, imploded. The ‘refugees’ (how few of them really deserve the name), the runaways, the panic-stricken, the pitiable herds of civilians are still in the village streets, the town squares and the roads, mixed in with the debris of the most powerful army—so we were told—in Europe. One sees women perched on gun carriages, where dishevelled ordinary soldiers are mixed up with civilians. It is true that not all images of these weeks have been so shameful and I know that one could find others. But I am convinced that they would not be the dominant ones.… Today, among many French people, I do not detect any sense of pain at the misfortunes of their country: during the days of this perfectly pure summer in these villages, towns and camp stations of Limousin, Périgord, and Guyenne, among so many civilians and soldiers … I have only observed a sort of complacent relief (sometimes even exalted relief), a kind of base atavistic satisfaction at the knowledge that ‘for us it’s over’ … without caring about anything else.2

Friedmann’s words certainly seem to match the experience of Captain Georges Sadoul, in civilian life a writer and journalist, who found himself on 16 June in Sully-sur-Loire. In front of the church he spotted a group of refugees who had been sleeping on straw in front of the porch:

I get down from the lorry. A woman speaks to me. I answer her. Then there are thirty of them at me, asking my advice, because I am a man, because I am in uniform, and because for hours they have found no one who can tell them anything.… One woman, red with anger and excitement, shouts out: ‘what are you waiting for, you soldiers, to stop this war? It’s got to stop. Do you want them to massacre us all with our children … why are you still fighting? That Reynaud, if I could get hold of him, the scoundrel!’3

The kind of scenes witnessed by Friedmann and Sadoul took place all over France in the last days before the armistice. They suggest that, whatever the errors of France’s military leaders, the deficiencies of its allies, or the defects of its political system, another possible reason for the defeat of 1940 was that the French people, whether soldiers or civilians, were not prepared to sacrifice themselves for the cause of the country as they had been in 1914. This was certainly the view of Gamelin, who managed to find the time on 18 May to draft a report for Daladier on the causes of the German breakthrough. Exempting himself from any responsibility, Gamelin pinned the blame for the defeat on the ordinary soldier:

The French soldier, yesterday’s citizen, did not believe in the war.… Disposed to criticize ceaselessly anyone holding the slightest amount of authority, and encouraged in the name of civilization to enjoy a soft daily life, he did not receive the kind of moral and patriotic education which would have prepared him for the drama in which the nation’s destiny will be played out.… The regrettable instances of looting by our troops at numerous points on the front offer manifest proof of … this indiscipline.… Too many of them have failed to do their duty in battle.4

To what extent was this criticism justified? In what ways was the attitude of the French population different from 1914?

The comparison with 1914 was in many people’s minds when war was declared in September 1939. William Bullitt wrote: ‘[T]he whole mobilisation was carried out in absolute quiet. The men left in silence. There were no bands, no songs. No shouts of “On to Berlin” and “Down with Hitler” to match the shouts of “On to Berlin” and “Down with the Kaiser” in 1914.’ In 1914, the words ‘To Berlin’ had been chalked on the sides of many trains; in 1939, Georges Sadoul saw them only once on the side of a lorry, but he saw many others daubed with the words ‘goodbye to love’ or ‘here go the men without women’.5

1914 was more than a memory. Most newly mobilized soldiers in 1939 found themselves passing through the killing-fields of that previous conflict as they set off to join their units. Private Gustave Folcher, a farmer from the Languedoc, had to cross almost the whole country to join his regiment on the Moselle. Looking out of the window as his train headed towards Metz, he saw ‘a huge cemetery with the crosses laid out in lines, left over from the war of 1914, which doesn’t do much to cheer us up’. Some weeks later, while on a training exercise, he visited an American cemetery near Thiancourt (near Belfort):

It is in silence that we leave this immense field of rest thinking of the thousands of men who sleep there, so far from their families, of their sad fate and of that which awaits us, for it is not encouraging for us in the situation in which we find ourselves to see almost everywhere these vast cemeteries of white or black crosses.6

Georges Friedmann was drafted into an ambulance unit near Laon. Travelling between Rheims and Laon on 10 September 1939, he noted:

We journey through all these villages, hills and forts whose names I had so often read as a child in the communiqués during the last war. Our driver, a prosperous local farmer from the area, knows every inch of the land. Here, he tells us, a section of chasseurs was destroyed by a machine gun nest; there a massive, a monstrous hole, its sides quite bare, reminds him that two companies were killed by a German mine in 1916; and along the road, here and there, we pass large fields planted with neat crosses.… All these names that were for me only names, fill with images: Craonne, Berry-au-Bac, le Chemin des Dames.

A month later Friedmann had a very disturbing encounter. Having set off on an expedition to pick mushrooms, he and a companion came across a lumberjack, about 60 years old, who seemed not to understand anything they said:

Then suddenly he begins to speak, in rapid and jerky phrases, in a dull voice, and tells us that he had been in the war. He had been at the Somme, in Alsace, at Douaumont (Verdun), where he was buried for a whole night in a shell hole. The next morning he could hardly hear any more: he was told that he would hear again once he was far from the shells. But it got worse and worse. He never heard again. He looks at our uniforms for a moment. And then, laying aside his axe, with an astonishing agility, he throws himself on the ground, mimes an attack, crawls forward, takes a branch to serve as his gun, puts it to his shoulder, fires, and then slowly, cautiously raises his head, as if in a trench, to see the result, loads his weapon, charges forward, throws himself to the ground.… This man of the forest relives his combats, perhaps he has lived with them, and only with them, for 25 years.

They ask if he has an invalidity pension, but he cannot hear the question. They try writing the question, but he cannot read. They leave him with a ‘reflex “au revoir” which is lost in the night’.7

If this individual, eternally immured in his memories of the war, was a particularly sad relic, there were few French men or women in the interwar years who did not live to some degree in the shadow of the Great War. 1.3 million Frenchmen had died in that conflict, and over 1 million survivors had been left as invalids. There were over 600,000 widows and over 750,000 orphans. The bodies of many who had died in the conflict were never recovered. At Verdun, scene of the most murderous battle of the war, a massive ossuary was built to commemorate those 300,000 soldiers whose bodies had never been found or identified. In every one of the 30,000 towns and villages of France, war memorials were built to honour the dead. These memorials still have the power to move us today; so much the more must this have been the case in the 1930s when they were so new, and so many living people remembered the names inscribed upon them.

Unlike Britain and Germany, France had also suffered from the fact that the war had largely been fought on its territory. By 1918 many cities in the north-eastern region of the country had been reduced to rubble; much rich agricultural land resembled a lunar landscape. One observer wrote in 1919: ‘[I]t is only after travelling day after day in an automobile through village after village and town after town, often where nothing is standing erect more than a few feet above the ground, that one can begin to have any conception of the enormousness of the destruction.’ The war zone was, in the words of another post-war witness, ‘a desert … corpses of horses, corpses of trees covering the corpses of men’.8 Some villages had disappeared forever. Still today there are fatalities almost every year from farmers coming across live shells. While the tracks for France’s high-speed train were being laid in 1990, 23 tonnes of unexploded shells were recovered in the Somme department. The rebuilding of this devastated area was one of the most remarkable achievements of the much-criticized Third Republic. By 1927 reconstruction was complete. Those ten years saw the rebuilding of some 800,000 farm dwellings, 20,500 public buildings, and 61,000 km of roads; over 3 million hectares of land had been cleared of barbed wire, trenches, and shells.

It is hardly surprising, therefore, that France had emerged from the war a profoundly pacifist society. Pacifism took various forms. There were ideological pacifists, especially among left-wing intellectuals and Socialists, who subscribed to a philosophical rejection of war in any circumstances. Such was the case, for example, of the novelist Jean Giono, who had been gassed in the war and almost lost his sight. ‘There is no glory in being French,’ wrote Giono, ‘there is only one glory: to be alive.’ In 1937 he published a collection of articles, Refus d’obéissance, which advocated desertion if war broke out. Pacifism of this kind was also widespread among the public sector workers, especially the postal workers and the 100,000 members of the primary schoolteachers (instituteurs) union (SNI). Among those who contributed to the SNI newspaper was the writer Léon Emery who coined the phrase ‘rather servitude than war’.

One of the most famous pacifists was Émile Chartier (known as Alain), whose position as teacher of philosophy at the famous Parisian lycée Henri IV gave him enormous influence over generations of young intellectuals, many of them, like Jean-Paul Sartre, destined for the elite École Normale Supérieure (ENS). If one ideology prevailed at the ENS in the inter-war years, it was pacifism. A big issue among students was whether they would agree to undergo the special training course (Préparation Militaire Supérieure (PMS)), which allowed those pursuing higher education to perform their military service as officers. The PMS was obligatory in institutions like the ENS, but in 1928 a majority of pupils signed a petition protesting against this. The future philosopher Raymond Aron, a signatory, recalls that he purposely failed his PMS course. Many instituteurs, who would normally have been expected to furnish a large contingent of reserve officers, also refused to do the PMS.

Those who subscribed to this uncompromising pacifism placed it above patriotism or Republicanism or indeed any ideology. Their patriotism had died in the mud of Verdun. But this extreme position was held by only a small minority, although an influential one. Most people subscribed to a kind of bruised patriotism that went hand in hand with a profound sense of the horror of war and a desperate desire to avoid it at almost any cost. This was the spirit of the Armistice Day ceremonies, which took place each year around the war memorial of every community in France on 11 November. It was sentiments of this kind that inspired the leading peasant organizations and war veterans associations. They did not reject patriotism, but they lived in the hope of reconciliation with Germany. This idealism was exploited by the Nazi regime, which sent an envoy to Paris to encourage pro-German feeling in France. This was Otto Abetz, a former German art teacher with a French wife. In 1934 Abetz organized a meeting between Hitler and two French war veterans’ leaders; in 1935 he set up a Franco-German Committee (CFA), which published a review and organized cultural and youth exchanges.

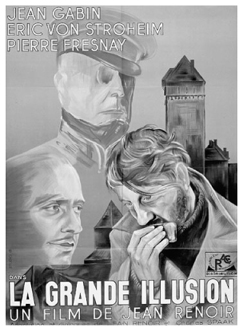

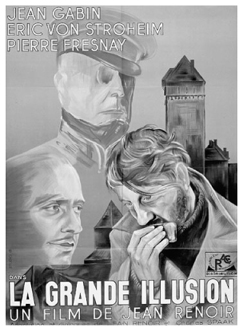

18. Jean Renoir’s La Grande Illusion, one of the most popular films of 1937, was the culmination of a whole series of inter-war anti-war films, starting with Abel Gance’s J’Accuse (1919). The ‘Grand Illusion’ is the idea that war solves anything. The film was banned in 1939

Pacifism and sympathy with Germany also existed in inter-war Britain. What was specific to France, however, was another current of pacifism born out of a sense that France’s vital energies had been sapped by the war. This was a pacifism rooted in exhaustion, in deep pessimism—or realism—about whether France could survive another bloodletting on the scale of the Great War. The French birth rate had been declining since the beginning of the nineteenth century. In 1800 France was the most populous country in Europe; by 1900 it had been overtaken by Germany and Britain. Thus the French casualties of about 4.1 million men in the Great War represented 10.5 per cent of the working male population—a higher proportion than in any other belligerent nation except Serbia. Even that uncompromising French nationalist, Georges Clemenceau, had declared after signing the Versailles Treaty that no treaty would guarantee France’s security if the French people did not start to have more children. It was these kinds of considerations that underlay the ‘realism’ of many French conservatives in the 1930s. The conservative deputy Louis Marin (who was in fact to be one of the members of Reynaud’s government who opposed the armistice) declared at the time of Munich that France could not permit itself the luxury of a Battle of the Marne every twenty years.

These different strands of pacifism all came together at the time of the Munich agreement. A petition, headed ‘We don’t want war’, was produced in September by the leaders of the SNI and the postal workers’ unions. It obtained some 150,000 signatures. Trade unionists like the SNI leader André Delmas worked behind the scenes with conservative politicians like Flandin to lobby against war. When Daladier landed at Le Bourget after returning from Munich there was a large crowd to acclaim him. Chamberlain was equally popular. There was a brief vogue for buying Chamberlain umbrellas—which people called ‘mon chamberlain’—and one paper set up a fund to buy him a country house in France. An opinion poll in October 1939, the first ever undertaken in France, showed that Munich was approved by 57 per cent of the population.

Munich was the high point of inter-war pacifism. The fund to purchase a house for Chamberlain closed after a month with only £1,500 received, and the supply of umbrellas outstripped demand. From the start of 1939, the balance of public opinion shifted dramatically, and the all-out pacifists, instead of representing the most radical wing of the moderate pacifist majority, found themselves isolated. The congresses of the two biggest war veterans’ associations, which had been ardently pro-Munichois, registered a more belligerent stance in the spring of 1939. The peasant press that had been fervently pacifist in 1938 was no longer so in 1939. In May, the former Socialist Marcel Déat, an ardent pacifist, wrote an article entitled ‘Do you really want to die for Danzig?’ His appeal was largely ignored or condemned. Within the Socialist Party, Blum’s supporters now triumphed over the pacifist wing at the Congress of May 1939. Already the poll taken after Munich had shown that 70 per cent of the respondents favoured resisting further German demands. In July 1939 another poll showed that 70 per cent of the population was ready to resist a German move against Danzig, by force if necessary. There were many reasons for this change of mood: the feeling, after March 1939, that Hitler had proved he could no longer be trusted; the patriotic mood created by Mussolini’s sabre-rattling demands for French colonies; the economic recovery that had started at the end of 1938; the popularity of Daladier.

19. Crowds cheering Daladier after Munich. He is shown here standing in his car in front of the Madeleine Church. When Daladier’s plane, returning from Munich, approached the airport, he was convinced the crowds had come to boo him. When he saw that the opposite was true, he muttered: ‘the idiots’

When war was declared in September 1939, the pacifist movement, so powerful a year earlier, seemed to have collapsed entirely. A manifesto calling for ‘immediate peace’ was published by the anarchist Louis Lecoin ten days after the declaration of war. The thirty-one signatories included all the usual suspects of the pacifist left, but after it was published many of them retracted their support, claiming that they had been misled about the use he intended to make of their names. Giono was put in prison for tearing down mobilization posters. The fact that pacifism could no longer be expressed openly did not mean that it had entirely disappeared on either right or left. On 30 August 1939, the headline of the extreme right-wing newspaper Je suis partout proclaimed ‘Down with War. Long live France!’. In the Socialist Party, pacifists like Paul Faure went into a kind of internal exile. Another Socialist, Ludovic Zoretti, ran a semi-clandestine newspaper, Redressement, which expressed the unreconstructed pacifism of many Socialists. But these were isolated voices which certainly, for the moment at least, expressed the view of only a small minority. France in 1939 was still a pacifist society, but one which had accepted, reluctantly, the necessity of war.

The French people may not have demonstrated great enthusiasm for war in 1939, but they did not show much opposition to it either. As in 1914, the number of soldiers refusing the call-up was tiny. ‘Resolution’, ‘gravity’, and ‘calm’ were the words most frequently used by the Prefects to describe the attitude of the population. ‘Something between resolution and resignation’ reported the Prefect of the Rhône. William Bullitt’s comment, quoted above, contrasting the situation in 1939 with 1914 went on to say of 1939 that ‘there was no hysterical weeping of mothers and sisters and children. The self-control and quiet courage has been so far beyond the usual standard of the human race that it has a dream quality.’ The British Ambassador talked of the population’s ‘quiet determination’. Of course such observers often saw what they wanted to see and their testimonies must be treated with caution. In plotting the evolution of opinion towards the war one must be sensitive to rapid shifts of mood, and to differences between different sections of the population.9

Even after the declaration of war, many people still hoped for peace. As one observer wrote of the war as he left to join his unit: ‘We knew war was coming since it was bound to come, but at heart one thought it might not come. And now 90% of people still think that it will be possible to reach an arrangement. I think so too. We must.’ But if people hoped for peace, they were determined to fight if it had to be war. That is certainly the impression one receives from the memoir of Gustave Folcher. Assigned to the 12th Regiment of Zouaves,10 Folcher had spent much of the Phoney War on exercises, moving around frequently and eventually being assigned in March to a sector of the line behind the Ardennes. During these months his life consisted of long marches and endless digging. His exhaustion, homesickness, and boredom were relieved by companionship and by the excitement of seeing a region of France he had never visited before. He found many of the villages of the Moselle region dirty and unappealing, but the countryside often attractive. The events that really mattered in his life as a soldier were a proper night’s sleep, a comfortable bed, a chance to put on clean clothes, ‘good coffee with rum served by nice young girls’. What is striking about his narrative is the narrowness of its horizons. The military leaders, the politicians, the enemy, the principles for which the war is being fought—none of these intrude. The war is accepted as a job to be done. Sartre noted a similar indifference to the world outside his unit: ‘I’ve never heard anyone mention Gamelin here. Never—not even to say something bad about him. He doesn’t exist.’11

This was also how many regimental commanders read the mood of their men. The colonel commanding the 77RI observed in January 1940: ‘Good morale. Not at all expansive, they give the impression of having little enthusiasm for this war.… But they are loyal, and like any good farmer, resigned to good and ill fortune, and one can be certain that they will hold out and will bring honour to the regiment.’12 Was this so different from the world view of the poilu of 1914–18?

As the waiting war dragged on into winter, all those reporting to the government on the mood of the population detected a slump in morale. Among civilians, resentment was fuelled by rising prices (despite Reynaud’s efforts). Peasants were angry that workers, often young, were being drafted from the front to the factories, while farms were allowed to fall into ruin. Once again it seemed that the peasants were being used as cannon fodder. There were floods of letters denouncing individuals who had obtained transfers from the front on allegedly fraudulent grounds. The mood in the factories was no better, even if they seemed a privileged haven to those outside them. Owing to Reynaud’s tax increases many workers in the arms industries were now putting in between 60 and 70 hours a week with little financial reward. A non-skilled worker in the Paris region who had previously earned about 400F for a 40-hour week now found himself earning 420F for 60 hours. Wage levels were pegged but prices were rising. In October 1939 the CGT and employers had negotiated an agreement (the Majestic Accords) on industrial cooperation, but the reality of the factory floor was still one of class revenge for 1936. One diarist commented in February: ‘I observe every day social divisions and class resentments which complicate and sully the conflict.’13

Among the soldiers at the front, the mood by December was reported to be one of ‘veritable demoralization’. The winter was the coldest since 1889—temperatures fell to –24°C in the east—and there were not enough socks and blankets to go round all the soldiers. Most debilitating of all for morale was a growing sense of lassitude and boredom after months of forced inactivity. This problem was less serious in the front-line regiments, where troops were kept busy with intensive training, but for the reserves this was not always possible owing to the lack of sufficient modern equipment. Much time was spent digging defences with spades.

Three diaries from the period tell a similar story. First that of Jean-Paul Sartre:

26 November 1939: all the men who left with me were raring to go at the outset but now they are dying of boredom.

20 February 1940: The war machine is running in neutral; the enemy is elusive and invisible.… The whole army is waiting in that ‘hesitant, timid’ attitude the generals wanted to avoid like the plague.… And the truth is that this waiting … hasn’t failed to have its effect.… Many people are hoping for an ‘arrangement’. Only yesterday a sergeant was telling me, with a gleam of insane hope in his eyes: ‘What I think is, it’ll all be arranged, England will climb down’. Most of the men are fairly receptive to the Hitler propaganda. They’re getting bored, morale, is sinking.

Secondly, Private Fernand Grenier:

15 November: Inactivity … The newspapers are less and less read; doubt has entered into people’s minds; they believe less and less what the papers say … The total lack of organised distraction, the monotonous routine of this dull army life means that the tiniest, most insignificant government announcement arouses discontent.

27 November: very few military exercises. The men are getting bored.

13 December: The days pass, interminable and empty, without the slightest occupation, without any other obligation beyond presence at the roll-calls in the morning and at midday.… The surprising tranquillity of the front ought to reassure us, help us to put up with our semi-captivity, which is at least without risks. But it only irritates us more. Why not send us home since we are doing nothing and there is nothing to do? … The officers, mainly reservists, think no differently from the men on this point. One feels they are weary of the war. They say and repeat that they would like to go home.

End January: militarily speaking we are doing literally nothing.… We are huddled around the stove, only going out for the two daily roll-calls. We are only provided with damp wood to heat ourselves.… We are so numbed with apathy and cold that many of us do not bother to wash, or to shave, to put on our shoes or even to undress properly when going to bed.… Departures on leave, and return from leave, are all that structure this life without incident. Most people return with their morale even worse than before.14

Sadoul’s unit of reservists, made up primarily of Parisians, was perhaps not representative in its composition, but the army services monitoring the soldiers’ correspondence picked up similar impressions. One typical letter of 20 February 1940 read: ‘nothing new here. I am bored to death. All we do is wait. But wait for what? This is the life of an imbecile and I am beginning to be completely fed up with it. Oh, let it end soon.’15 Thus, Sadoul was probably right when, having met other soldiers in the train during his leave, he reflected that ‘our little microcosm … is the barometer of a general mood’.

This deterioration of morale, both in the army and among civilians, was not ideologically motivated. The government was obsessed by Communism, but the effect of Communist propaganda was negligible. The Communists produced an underground copy of their newspaper L’Humanité (banned since September 1939) and a special newspaper for soldiers that was just a cyclostyled sheet. In fact although the Communists argued for an immediate peace on the grounds that the war was an imperialist conflict and against the interests of the French workers, they did not advocate revolutionary defeatism, desertion, or fraternization with the enemy (at least as long as the war was not against the Soviet Union), and told their members to obey orders and perform their duty—which seems to be what most of them did (Grenier and Sadoul were both Communists). But the relentless anti-Communist propaganda must have been enough to make some ordinary Communists wonder in what sense this was their war.

As for the factories, subsequent allegations that Communist-inspired workers carried out sabotage were largely groundless. The Communist Party did not in fact advocate sabotage, although it did urge the workers to protest against working conditions and slow down production. The only proven case of sabotage took place in the Farmann factory. It was the work of a tiny group of Communists—two of them brothers—acting on their own initiative. Three of them were shot on 22 June, just before the signing of the armistice. It is impossible to say if the production difficulties in certain arms factories were due to political motives. The shortfall in aircraft production in the Phoney War was attributed by one general to ‘the nonchalance of the large majority of workers and the lack of authority of the cadres’.16 But the most striking fact about the Phoney War was the total lack of industrial unrest: in the factories the labour force had never worked harder. In the whole of the Phoney War, only two cases of labour unrest were registered in the Renault factory. The mood, however, was certainly not one of enthusiasm. Even a very conservative employer like the steel magnate de Wendel worried that the logic of Reynaud’s tax levies was operating as a disincentive to effort.

The Communist Party had been so weakened by government repression and by defections in the wake of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact that its anti-war propaganda had little impact. More serious, however, was the ineffectiveness of official propaganda in favour of the war. The army spent time organizing entertainments for the troops, but failed to explain why the war was being fought in the first place. Answering this question was supposedly the task of the Propaganda Commissariat, which had been created by Daladier in July 1939. It was headed by the writer Jean Giraudoux, who had made his reputation in the 1920s with works denouncing militarism and in favour of Franco-German reconciliation. His best-known work was the anti-war play The Trojan War Will Not Take Place (1935).

This was a curious pedigree for someone whose responsibility was to organize propaganda against Germany, and it was generally agreed that Giraudoux’s Commissariat was a disaster. He recruited a galaxy of intellectual luminaries—the writer André Maurois, the director of the Bibliothèque Nationale, Julien Cain, the historian Paul Hazard—but he was no organizer, and his headquarters at the Hotel Continental was a den of intrigue, gossip, and infighting. Maurois soon gave up in disgust. The fastidious and literary tone of Giraudoux’s radio broadcasts either passed over the heads of his listeners or alarmed them, as in his broadcast of 27 October evoking the ‘the Angel of Death’ stalking over the sleeping armies.

But Giraudoux did not have an easy task and was not to blame for all his problems. He did not have ministerial status, and his budget was small (minuscule compared to Goebbels’s). The army did not take propaganda seriously. While the German High Command employed good photographers and released thousands of pictures to the press, the French army was more secretive; the press often had to be content with dull photographs of Parisians strolling in the Champs Élysées (it is also true, of course, that the Germans at least had some victories to boast about).

Giraudoux’s main handicap, however, was that the government provided no guidance as to how it wanted him to present the war. A generation brought up on memories of First World War propaganda lies (bourrage de crâne) was predisposed to be suspicious. Sartre noted:

The public is so used to the idea of official lies that the speeches of Daladier and Chamberlain affirming their ‘unshakeable resolution etc.’ leave them cold.… There is an a priori suspicion towards the most innocent news in the papers—which derives from what they have been told about the ‘bourrage de crâne’.

Patriotic rhetoric on the model of 1914 would not have worked in 1940. As Folcher recounts: ‘[T]he CO, on parade, makes a little speech, in which he declares that our fathers in the other war, the Great one (this one presumably being the Small one), went to the trenches singing; which caused one of the men to reply that the few who returned came back crying.’ Attempts to revive the famous First World War song La Madelon were totally unsuccessful. The most popular song of the Phoney War was the wistful love song ‘J’attendrai’ (‘I will wait, day and night / I will wait always / I will wait your return’). Obscene songs were also popular. On one occasion Sadoul heard soldiers singing the tune of La Madelon but with the words ‘Madelon! Madelon! Madelon!’ replaced by ‘Du croupion! Du croupion! Du croupion!’ [‘Arse, Arse, Arse’]; on another occasion someone in the barracks who tried to sing Madelon and then the Marseillaise was shouted down on both occasions.17

What, after all, were Britain and France fighting for after the collapse of Poland? Presenting the war as an anti-Fascist crusade was ruled out by the government’s desire to avoid any provocation of Italy (and to avoid alienating French conservatives). In a broadcast in October 1939 Daladier specifically declared that this was not a war against Fascism; the censors were instructed to bar any slighting references to Mussolini. In the end the ineffectiveness of propaganda reflected the divisions and uncertainties of the French people.

One vivid illustration of the failure of propaganda was the impact of the pro-German broadcasts by the French journalist Paul Ferdonnet broadcasting from Radio Stuttgart. Hitherto an insignificant figure on the fringes of the extreme right, Ferdonnet acquired notoriety when the government revealed his existence in October. The most effective theme of his broadcasts was that Britain would fight to the last Frenchman: ‘Britain provides the machines, France provides the men.’ It does not seem that many people actually heard the broadcasts—though it is surprising how much they are mentioned in diaries and memoirs of the period—but they contributed to a sort of psychosis about the existence of a fifth column. Ferdonnet would broadcast a piece of military information, and when it proved to be correct the rumour spread that he was being fed information by a team of spies, although he knew nothing that could not be gleaned from the French press. Rumours of his omniscience were demoralizing, and soldiers who had not heard his broadcasts often wrote home to announce, completely fallaciously, that some recent manoeuvre of their regiment had been announced beforehand on Radio Stuttgart. The British consul in Marseilles reported at the end of December:

The expression of dissatisfaction to be heard in the market places not infrequently takes the form so familiar to us from the German broadcasts that I fear German propaganda has had some success with the meridional people.… There are even some who refuse to believe that British troops are on the Western front and declare that no reliance can be placed in the newspapers.18

The government was fully aware of the poor state of morale, and Daladier’s obsession with Finland was partly due to his need to offer the French population some kind of military success. Despite the capitulation of Finland, the mood did begin to improve during the spring. This had nothing to do with the replacement of Daladier by Reynaud, who was not popular in the country. After Reynaud took over, Sartre noted: ‘The men here are reproaching Reynaud for not having said a word in his broadcast address about “the heroism of our valiant soldiers”. “That Daladier, he’d never have missed that out!” they complain sadly.’ The improvement in morale may have owed as much to the weather as anything else. The monitors of correspondence noted of one regiment on 23 April that only 13 out of 5,864 letters revealed an unsatisfactory attitude. In all the surveys of correspondence between 25 April and 10 May army morale was described as ‘excellent’, ‘very good’, or ‘good’. Given that this positive estimation included the 55DI and the 71DI, both of which were to collapse dramatically at Sedan, one might question the value of such surveys. Obviously it is impossible to reach any kind of scientific precision with a notion as subjective and nebulous as ‘morale’. Moods can change very quickly according to circumstances. The attitude of soldiers whose disaffection was born largely of boredom and lack of motivation could change overnight once the enemy attacked—once inactivity was replaced by a clear and palpable danger. What happened then would depend on how prepared the soldiers were to carry out the tasks allotted to them.19

The French army was not a monolithic organization.20 There were huge differences in fighting quality between the active units, the twenty Series-A reserve divisions and the eighteen Series-B reserve divisions. After a period of active military service (eighteen months from 1923 to 1930, one year from 1930 to 1935, two years from 193521), each adult male was liable for twenty-seven years’ further service: three years in the ‘ready’ reserve, sixteen in the first line reserve (A-Series), and eight in the second line reserve (B-Series). Overall there was supposedly up to ten weeks’ reserve training.

The introduction of one-year service had complicated the task of training conscripts in time. They were incorporated biannually in two contingents so as to ensure that France was always defended by half a contingent of partially trained men. But this meant that at any one moment the army was dealing with three categories of soldier. The presence in every unit of men at different stages of training disrupted tactical organization. Furthermore the real training period was considerably less than a year, taking account of days lost in the break between the two annual contingents, in the induction process, in holidays, agricultural leaves, and so on. It was estimated in 1930 that 18 per cent of the riflemen in an average regiment had never fired a rifle and one-quarter had never thrown a grenade. Sartre noticed during the Phoney War the ‘respectful terror’ with which a fellow soldier handled an ‘unloaded and obsolete’ revolver; Fernand Grenier observed that only two out of twenty men in his unit knew how to use the grenades they received in June 1940.

The army was particularly worried by the quality of its reserve officers and NCOs. Reserve officers were supposed to take refresher courses, and were given financial incentives to do so, but many did not bother. Many men whose level of education would normally have led them to be officers served only as common soldiers because, owing to the anti-militarism prevalent among intellectuals and instituteurs, they had refused to perform their PMS. Jean-Paul Sartre and Raymond Aron, two intellectuals very representative of their generation, had both done their military service as ordinary soldiers in the meteorological section. An exercise in 1934 to test a representative reserve division, the 41DI, concluded that the reserve officers and NCOs were unprepared, and the men unfit and demoralized by poor leadership.

Recruitment was organized geographically. This was supposed to overcome some of the problems caused by short active service, since it allowed units to acquire cohesion by training together over time. The reality was different. The principle of geographical recruitment was often breached for practical reasons. For example, rural Breton units received drafts from cities to increase the supply of literate NCO material, armoured battalions required a certain proportion of men with driving licences, and so on. Once soldiers joined the reserve, however, they came under the authority of their local mobilization centres, which did not send reservists back to their former active comrades if this involved dispatching them long distances for brief training periods. Whatever cohesion did exist on mobilization frequently disappeared as a result of all kinds of shifts of personnel such as the dispatch of 100,000 mobilized workers to industry during the Phoney War, or the decision in December 1939 to move younger soldiers on the Maginot Line to mobile units and to move older soldiers to fortress duties. This broke up well-trained fortress crews for the dubious advantage of mixing younger soldiers with the B-Series soldiers. Thus, to quote one historian of this subject, the ideal of a cohesive reserve army ready to spring into action on mobilization was in reality ‘an army of makeshift units—constantly shifting their personnel, never testing their wartime organisation and resigned to training in ad hoc units and with borrowed equipment—led by inexperienced junior officers and NCOs’.22 Private Grenier observed that the 100 men in his company of engineers came from the north, the east, the Alps, the Midi, and Paris. One detachment of six men comprised one Savoyard who had done his active service in Syria, one from Épernay, one from Marseilles, Grenier himself from Paris, and two drunkards (of unknown provenance).

The Phoney War should have allowed time to overcome these training deficiencies. With many weaker divisions, however, the opportunity was often squandered either owing to lack of equipment or because there was an insufficient sense of urgency. Pierre Lesort, a reserve officer posted in March 1940 to the 120th Infantry Regiment of the (subsequently infamous) 71DI23 (part of the Second Army), was shocked by what he found. His company lacked training or equipment, and their living conditions were squalid. He did his best to improve the training of the machine-gunners in his section, but the experience was dispiriting:

The ambiance strikes me as very lax as regards discipline; one must remember what sort of life these men have been leading for the last six months, shivering in this mud. The material conditions are bad; men are on straw on the ground, the walls are dirty and things are strewn up everywhere.… The platoon has been under the command for 4 months of a deplorable sergeant and everything has been allowed to go to seed; the men have got used to doing nothing, the two camps are revolting … like a gypsy encampment … the trouble is that we lack every kind of material, even planks to make beds.… Luckily morale doesn’t seem too bad; the men have accustomed themselves passively to the appalling conditions in which they are living, and the only problem is to drag them out of their inertia. Unfortunately we lack the time to do the work to improve the living conditions since we have the whole time to carry out fatigues for the engineers, to dig trenches, unload sacks of cement.

A few weeks later things had got worse:

I am absolutely disgusted by this company. All my efforts come to nothing except that I am seen as an interferer … I am after all only a platoon commander.… Unfortunately it is impossible to instil a sense of esprit de corps, discipline and work into a section in the middle of this dump of a company. In my section there are one or two individuals who are just thugs.24

Corap was extremely worried about the state of his Ninth Army soldiers. In February he worried about ‘slackening of discipline in certain billets … soldiers insulting and sometimes attacking local inhabitants’. In the next months he noted ‘an unacceptable slovenliness, men badly turned out, not saluting or saluting sloppily, nonchalance and inactivity’; he received reports of widespread drunkenness and of soldiers causing scandals in stations by singing the Internationale.25 These descriptions of the Ninth Army certainly seem to bear out the impressions of the British General Sir Alan Brooke, who had watched a parade of Ninth Army troops in November 1939: ‘Seldom have I seen anything more slovenly … men unshaven, horses ungroomed … complete lack of pride in themselves or their units. What shook me most, however, was the look in the men’s faces, disgruntled and insubordinate looks.’26

‘This time it’s the real war; so much the better since at last we can see the end.’ ‘If you knew how confident and full of hope I am.’27 These two comments come from letters written by soldiers of the 21DI between 11 and 13 May as they headed into Belgium after the German invasion. They should remind us that the soldiers’ demoralization during the Phoney War represented not so much hostility to the war in itself as boredom caused by waiting for a war that never seemed to come. Thus, many soldiers greeted the news of Germany’s invasion of Belgium with relief.

The confidence displayed by these soldiers, of course, assumes an ironic hue in the light of what was about to occur, but in fact the story of the French army in 1940 cannot be reduced to the disastrous events on the Meuse. There were many examples where French soldiers, properly armed, properly trained, and properly led, fought just as effectively and courageously as their celebrated poilu forerunners.

This was certainly true of the two DLMs of General Prioux’s cavalry at Hannut on the Belgian plain on 13 May (the same moment that the Germans were breaking through at Sedan). This was the first tank battle of the war, and it was won by the French in difficult conditions. There is some dispute as to the exact numbers of tanks arrayed on each side. The most recent French authority claims about 650 German tanks and 320 French, but if the light German tanks (Panzer I and Panzer II) are not included among the German forces, the French enjoyed superiority. Some historians also criticize Prioux for deploying his tanks in too linear a fashion, and displaying insufficient manoeuvrability. But all accounts agree that the French fought well, although the 3rd DLM, which suffered the brunt of the attack, had only recently been formed. Despite the Germans enjoying total air superiority, the French fulfilled their mission (which was of course to act as a decoy, but they could not know that).

Once Prioux had fallen back, the task of holding the Germans in the Gembloux gap fell to the newly arrived divisions of the First Army, in particular the First Moroccan Division and the 1st Motorized Division. The former was an only partially motorized unit that had covered 135 km of the journey on foot. The last soldiers only arrived on the morning of 14 May and were still preparing their positions, under enemy air attack, when the German tanks moved against them. Encounter battles of this kind were precisely what Gamelin had wanted to avoid, but for two days the Germans tried to break the line without success. The French held firm thanks to the determined resistance of their infantry and the effective performance of their artillery. This was a rare example of infantry stopping an armoured division in open country, without air support. When the French fell back on 16 May, it was not because they had been beaten but because the Germans had broken through on the Meuse.

Even on the Meuse, apart from the case of Guderian at Sedan, the German crossings were not as easy as is often suggested. The most effective French resistance occurred at Monthermé between 13 and 15 May when a thinly spread French defence (the Half Brigade of Tirailleurs Coloniaux) held off a Panzer division for two days until the collapse of the French resistance on their flanks made the position untenable. Rommel’s crossing at Dinant also encountered strong resistance, although the defenders were not in an easy situation. At one moment Rommel had even feared that some of his troops were about to lose their nerve. Even after his men had established a foothold on the other side of the river on the night of 13–14 May, the French fought hard despite the breaching of their defensive line. There was no panic. For the second time Rommel had to throw himself into the thick of the battle in order to prevail. One of his company commanders, Captain Hans von Luck, wrote: ‘His command tank was hit and the driver put it into a ditch. Rommel was slightly wounded, but hurried forward on foot—in the midst of the enemy fire.… It made a strong impression on all the officers and men.’28

It would be wrong to assume that, even once the Germans had broken through the three bridgeheads, their advance westwards was simply a mopping up operation. We should not forget, for example, the very fierce resistance of the 3rd DCR and 3rd DIM at Stonne to the south-east of Sedan between 15 and 25 May. Hard fighting was still going on here when the Germans had reached the Channel.29 Tenacious resistance was also demonstrated by the remnants of the First Army caught in the jaws of the German trap and knowing that the outcome was predestined. In Lille, about 30,000–40,000 soldiers of the First Army held off massively superior German forces between 28 May and 31 May, despite being entirely surrounded and relentlessly bombarded by artillery fire. The Germans had to fight their way through the suburbs while the French held on wherever they could—in factory buildings, apartment blocks, behind improvised barricades—until all ammunition was exhausted. One regimental commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Dutrey, committed suicide rather than surrender. Although they may not have realized it, these soldiers had held off the Germans long enough for the BEF and part of the French army to reach the Dunkirk bridgehead.

The bridgehead of Dunkirk itself was defended between 29 May and 4 June by about 8,000 soldiers left over from the 12DIM (one of the divisions of the First Army which had been at Gembloux fifteen days earlier). Their commanding officer, General Janssen, was killed on 2 June. The miracle of Dunkirk, we should remember, was made possible by Gort’s foresight, Hitler’s loss of nerve, British resourcefulness, and French heroism.

The story was of course different at Sedan on 13 May. This sector was defended by the 55DI of the Second Army. Many soldiers in this B-Series division had performed their military service up to twenty years previously. Only 4 per cent of its officers were regulars. Training during the Phoney War had been hampered by shortages of material. The major deficiency was in anti-aircraft weapons and anti-tank guns. The standard density of anti-tank guns in defence was meant to be ten weapons per km, but in this sector it was less than four per km. In the end, however, this hardly mattered, since the division had collapsed before German tanks crossed the Meuse in significant numbers.

On this sector of the line the Germans enjoyed significant local superiority: the first line of resistance on the left bank of the Meuse, between Wadelincourt and Bellevue, was very spaced out along 10 km of the bend in the river. The 55DI’s sister regiment, the 71DI, was considered to be barely ready for battle. Originally it had been placed on the right of the 55DI, but it was withdrawn for training in April. On 12 May it was ordered forward again, and these troop movements only caused confusion at such a crucial moment. One unit that played a key role in the defence was the 147th Fortress Infantry Regiment, under the command of Lieutenant François Pinaud. This unit found itself bearing the brunt of the German attack on 13 May. Of the four main crossings made by Guderian’s XIX Panzer Corps, three were in the 147th’s sector. Pinaud’s unit comprised B-Series troops, mostly from the Ardennes and Aisne regions, and from Paris. One-third of them had originally been conscripted from 1918 to 1925, another third from 1926 to 1925. This meant that the average age of an ordinary soldier was 31 and a captain 42. Their level of training was not high. To remedy this, the men had been rotated through training sessions, but once these were over they were not always returned to where they had originally been stationed. Thus, although the 55DI as a whole had been in the Sedan region for months, Pinaud’s men had been moved around a lot. When the Germans attacked none of the nine companies under his command was occupying a position it had been in for more than a month.

Even taking account of all these problems, there is no doubt that the performance of this regiment, and of the division in general, was exceptionally poor. To explain this, it is impossible to overestimate the impact of the eight-hour aerial bombardment that preceded the German crossing. Nothing had mentally prepared the men, cowering in their shelters, for this. If the bombardment did not succeed in destroying the French bunkers or gun emplacements, its psychological impact was incalculable. In the words of General Ruby, Deputy Chief of Staff of the Second Army:

The gunners stopped firing and went to ground, the infantry cowered in their trenches, dazed by the crash of bombs and the shriek of the dive-bombers; they had not developed the instinctive reaction of running to their anti-aircraft guns and firing back. Their only concern was to keep their heads well down. Five hours of this nightmare was enough to shatter their nerves and they became incapable of reacting against the enemy infantry.

One significant material effect of the bombardment was to destroy telephone communications. This cut the defenders off from each other, since they were not allowed to use radios in case their messages were picked up by the enemy. Their sense of isolation aggravated the psychological effects of the bombardment. Some men were reported to be stunned to the point of derangement, as sometimes occurred after particularly heavy artillery bombardments in the First World War. Especially unnerving were the screaming Stuka dive bombers, hurtling down on the cowering French defenders, their sirens screeching: ‘The noise, the horrible noise! … You feel the bomb coming even if it falls 50 or 100 yards away. You throw yourself on the ground, certain of being blown into thirty pieces. And when you realise that it is only a miss, the noise of this shrieking shatters you.’30

Then there was the demoralizing sense that the sky was empty of British or French planes:

A hundred and fifty German planes! It is breathtaking! The noise of their engines is already enormous, and then there is this extraordinary shrieking which shreds your nerves.… And then suddenly there is a rain of bombs.… And it goes on and on and on! … Not a French or British plane to be seen. Where the hell are they! … My neighbour, a young bloke, is crying.… Nerves are raw.… Few men are actually hit, but their features are drawn, tiredness rings their eyes. Morale is affected. Why are our planes not defending us? No one says it, but everyone is thinking it.31

For those watching from the other side of the river the effect was hardly less dramatic. One German sergeant reported:

Squadron upon squadron rise to a great height, break into line ahead and there, the first machines hurtle perpendicularly down, followed by the second, third—ten, twelve aeroplanes are there. Simultaneously, like some bird of prey, they fall upon their victim and then release their load of bombs on the target.… It becomes a regular rain of bombs, that whistle down on Sedan and the bunker positions. Each time the explosion is overwhelming, the noise deafening. Everything becomes blended together; along with the howling sirens of the Stukas in their dives, the bombs whistle and crack and burst.… We stand and watch what is happening as if hypnotised; down below all hell is let loose! At the same time we are full of confidence … suddenly we notice that the enemy artillery no longer shoots … while the last squadron of Stukas is still attacking, we receive our marching orders.32

The first Germans crossed the Meuse at 4 p.m. on 13 May. For the French defenders, this was the moment of truth. As Alistair Horne writes:

Suddenly the great, complex stratagems of both sides, in which armies are moved around like chess pieces, become reduced to the isolated actions of one or two men.… The success or failure of such lone combats leads to the success or failure of a platoon, from a platoon to a company, from a company to a regiment, and so on until the whole battlefield is in flux and the day is decided.33

20. The German Ju 87 dive bomber, popularly known as the ‘Stuka’. The pilots would swoop down at 70 to 80 degrees from an altitude of 10,000 feet and pull out of their dive at 3,000 feet or lower. The aircraft were fitted with sirens which emitted a high-pitched shriek

The troops of the 147th Fortress Infantry Regiment, already demoralized by the aerial pounding, were unlucky enough to be facing the tough troops of the 1st Rifle Infantry Regiment commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Balck. The speed with which the Germans moved up the river bank and took the first French bunkers suggests that the resistance was weak and the defenders badly demoralized. This was only the beginning. Some individual infantrymen had already started fleeing during the early afternoon, but a few hours later panic spread to the artillery. Some time after 6 p.m., the commander of the 55DI, General Lafontaine, who was at his command post behind Bulson, a village 4.5 km south of Sedan, heard shouting outside. He went out to see what was happening. As General Ruby tells the story:

A wave of terrified fugitives, gunners and infantry, in cars, on foot, many without arms but dragging kitbags, was hurtling down the Bulson road screaming ‘The tanks are at Bulson.’ Some were firing their rifles like lunatics. General Lafontaine and his officers rushed in front of them, trying to reason with them and herd them together, and had lorries put across the road.… Officers were mixed in with the men.… There was mass hysteria. All of them had supposedly seen tanks in Bulson.34

Lafontaine thought that he had stopped the flood, but he was to discover that it had spread elsewhere behind the lines when he decided to move his command post to the village of Chémery, 8 km south-west of Bulson. Arriving in Chémery at about 7.15 p.m. he found the village crowded with soldiers fleeing south from Sedan by the other north–south road in a state of indescribable panic, lighting the powder trail of rumour as they fled further south. About 37 km south-east of Bulson, at Flaba, was the command post of the X Corps artillery (the 55 and 71DI were both part of the X Corps). Its commander, Colonel Poncelet, was visiting a subordinate unit when the rumour that German tanks were close reached his command post. At about 7.45 the decision was taken to move to an alternative post. Poncelet quickly realized that there was no need for this and returned to his post, but by then most of its communications equipment had been destroyed in the flight.

The ‘Bulson rumour’ also spread east: by 10.30 p.m. it had reached Rethel. By dawn the next morning soldiers in flight were milling around Vouviers, many of them looting farms to satisfy their thirst and hunger. One eyewitness reported:

They seemed so eaten up by fear that they terrified each other during their retreat with more and more fantastical stories, as if they wanted to forbid themselves any hope of return.… Many were without their bags or arms and they did not seem concerned to recover them. They only wanted to get away.35

Overall some 20,000 soldiers fled in the Bulson panic. Although it started among the artillery, eventually every type of unit was affected. But the collapse of the artillery, traditionally the glory of the French army, was particularly significant for an army that placed such emphasis on the importance of firepower. The sight of this panic also had a catastrophic effect on the morale of other units that were at the same time being sent forward to reinforce the front line.

Why did it happen? The rumour that German tanks were at Bulson was quite false. No German tanks had crossed the Meuse at this stage, and it was to be six more hours before they did. The origin of the rumour is unclear. Some suggest, with no evidence, that it was started by German fifth columnists. More probably, some fleeing French soldiers had mistaken French tanks for German ones. The decision to move Lafontaine’s and Poncelet’s command posts certainly contributed to the sense of chaos. When no one answered the telephones in these deserted command posts there was understandable alarm. In Lafontaine’s case the move was apparently intended to allow him to organize a counterattack more effectively, but it contributed to the soldiers’ sense that they were being abandoned by their commander. ‘We have been betrayed’, ‘our officers have abandoned us’: such phrases were on the lips of many of the fleeing soldiers. Poncelet committed suicide on 24 May, apparently acknowledging his unwitting role in the disaster.

The exact origins of the Bulson rumour will never be known. But in more general terms it is not hard to explain the collapse of the 55DI—and to do so one does not need to invoke any kind of rottenness in the French body politic. These were ill-trained and ill-equipped troops, not originally intended for battle duty, whose cohesion had been weakened by frequent swapping of personnel, and who had found themselves facing an aerial onslaught for which they were mentally and materially unprepared in every respect. They were the wrong men in the wrong place at the wrong time.

The collapse of the 55DI was followed on the next day by that of the 71DI, another B-Series division. One of its regiments (205RI) had already been sent in for a counterattack on the evening of 13 May. The soldiers’ spirits were not raised by encountering fugitives coming in the other direction shouting ‘Don’t go forward! The Boches are there!’ In the end, on the next morning, the 205RI was ordered to fall back before it had even fought owing to the failure of the counterattack that had been undertaken by General Lafontaine in the early morning.36 This withdrawal further confused the men, and turned into a rout. Two other regiments of the 71DI (246RI and 120RI) were dispersed into companies to form defensive points (points d’appui) facing west along the flank of the German advance. These units were isolated from each other—communications with the divisional commander, General Baudet, had broken down—and some could see enemy tanks moving along the road to their south, that is behind them. Increasing numbers of men could see no alternative but to escape before it was too late.

In many accounts of the Fall of France, the fate of the 71DI figures as an even more humiliating development than that of the 55DI on the previous day, since most of its units had not even fought at all. There was no single moment of panic as occurred at Bulson. Rather there was what several historians describe as a kind of ‘molecular disintegration’; the division is seen as having ‘vanished into thin air’ (volatilisée). It is all too tempting to see its unhappy end as symbolic of the supposed demoralization of the French army in 1940. In one notorious incident, which figures in many accounts, Colonel Costa of the 38RA, seeing men of the 71DI in flight, tried to block their way and reason with them, but met with the response: ‘[W]e want to go home and get back to work! There is nothing to do! We are lost! We are betrayed!’

Here it is necessary to remember how different the smooth and simplifying narratives of military history can be from the muddled and messy reality of battle. Phrases like ‘molecular disintegration’ or ‘volatisée’ are only metaphors. What did this actually mean for the soldiers who experienced these events? Pierre Lesort, whom we have already encountered in the Phoney War, was caught up in them as a part of the 120th regiment of the 71DI. With painstaking scrupulousness he has tested his own memories, and his contemporary letters, against subsequent historical accounts. In the end he finds that none of them successfully captures the reality of his experience. The often-repeated anecdote of Colonel Costa turns out to be a classic case of historical ‘piggybacking’, as Lesort traces it back from historian to historian, from Henri Amouroux (1976) to William Shirer (1969), to Alphonse Goutard (1956), and so on until he finds its origin in a somewhat polemical work written during the Occupation by a strongly pro-collaborationist author, Paul Allard. So tainted an original source should certainly make one suspicious of the accuracy of this otherwise entirely unverifiable anecdote, but even if it were true, only a massive historical sleight of hand can make it stand for the ‘truth’ about the 18,000 men of an entire division or even the 3,000 in a regiment.

On 13 May, Lesort’s detachment found itself manning one of the defensive points in the hills north-east of Angecourt above the Meuse. German air bombardment started at around 10 a.m. Of the description of this event by General Ruby, as quoted above here (and by many other historians), Lesort observes:

I have no idea where General Ruby derived his own personal observation of the front lines on the ground itself; I only know that he was deputy chief of staff of the Second Army whose HQ was at Sennuc about 40 km to the south of the Meuse at Sedan. I can only say what I saw, heard, lived and have kept in my memory.… I saw very well, about 800–1000 metres on my left, an artillery battery … which never stopped firing at the diving Stukas which ceaselessly attacked it: I can still see the little round clouds which its guns created in the sky around the swirling planes which continuously dispersed and returned.… As for the reactions of the machine-gunners in my company, we never stopped shooting desperately at the planes.… It must be said that this control of the sky by the Germans for these two days made the men discontented and impatient. At the start it was just a sort of grumbling: ‘Christ, there are only German planes, what the hell are ours doing?’ But on the following days … one felt the growth of a kind of helpless resentment which corroded our need to find reasons to hope. But on the evening of 14 May it only needed two French fighters to appear in the sky behind us chasing and bringing down two German planes to sweep away that sense of humiliation which can be such a dangerous internal enemy for the infantryman who knows he is so badly armed against planes, artillery and tanks.

When the men saw the planes, a cheer went up. Then, on the evening of 14 May, they heard that the Germans were at Angecourt and that the entire battalion was to fall back towards the village of Yoncq. Lesort’s detachment of about twenty men was ordered to move. As they set off at about 3 a.m., his feelings were mixed:

Thirst, fear, solitude … And yet, despite all this, a memory of a certain light-headedness? First, no doubt, because of the confidence, which seemed mutual, between my machine-gunners and me … Confidence also, of another kind … How to describe it? In events? In the future? In the French army? I was certainly none too optimistic for the immediate future. I had been too angry over the last few months, about the weakness of the means at our disposal and the indifference of too many of our leaders. I was not really surprised that the Germans had broken through on our left; I knew only too well the men and arms in our poor division.… But I did believe in the existence of a genuine organized ‘second position’, and above all in the presence, behind us, of reserves composed of better armed divisions, notably of mechanized and armoured units. From my narrow vantage-point of head of an infantry section, as dawn broke, we were going to remain here until at H hour, in accordance with our mission … we would fall back at the fixed moment, in silence or under fire, leaving behind some dead (among whom might be me), but the survivors would rejoin solid lines which had been formed behind the units which had been outflanked, they would take their place in their companies, and they would be used again in the battle which was beginning.

After five hours zigzagging through the woods, and avoiding the roads as much as possible, laden with equipment and almost crazed with thirst, they reached the village of Yoncq in the early hours of 15 May, to find that it was under attack from German tanks. Briefly caught up in the fighting between the Germans and the French defenders above Yoncq, they continued their journey south-west, having received some indications about the location of their battalion.

We arrived at a cross-roads, somewhere between Neuville and Buzancy [this puts them about 35 km south of Sedan]. On the road coming from our right (thus from the north) appeared a procession of small groups and isolated individuals. An immediate impression of total disorder and shameful despair. Belongings pushed on bikes, helmets and guns out of sight, and the appearance of dazed vagrants … How many men? A few dozen?

By the side of the road a man was standing alone, immobile. Wearing a black cap and short cassock: a military chaplain … I approached him to ask if he had any idea of the whereabouts of my unit, and when he looked round at me I saw that he was crying. I asked him my question, but he did not know. I didn’t insist. I had other things to do than offer sympathy. Had he perhaps tried to talk to these men in flight? I don’t know.… What I recall is my feeling: fear of contagion for my own men, and so a desire to get away; I didn’t want to wait around; my men picked up their arms and went on marching with me, and we continued our journey west. It was a strange road, so deserted at times, and then suddenly encumbered by convoys going in either direction … an immense racket of engines, human voices and neighing horses. And above all this, in the sky, the enemy planes were humming, passing over, disappearing, returning.37

Finally, after some thirty-six hours, late on 16 May they made contact with their regiment near Boult-aux-Bois.

Gustave Folcher found himself in exactly the same sector, and his account, written quite independently, is in many respects similar to Lesort’s. His regiment was part of the 3rd North African Infantry Division, which was a unit of regular soldiers forming part of the Second Army. On 13 May, they were on the high ground above the Meuse, slightly to the south-west of Sedan, when the aerial bombardment began:

It was terrifying to see those machines diving at us, spitting out their bombs with a shrieking which, we assumed, was made by the bombs as they fell. In any case the noise was terrible, and despite ourselves we were far from reassured. We quickly dug a hole and made a kind of parapet with the stones and earth. There we felt safer … and we even became bolder, and each time the planes came back we emptied our guns at these balls of fire which seemed to mock our poor rifles.… One thing surprised us, something we hadn’t at first thought about in the panic of the morning, and now which was on everyone’s lips: what were the British and French planes doing? How come there was not a single one to be seen?

On the night of 13 May they were ordered to fall back, and they arrived in the early hours of 14 May at a village they later ascertained to be Yoncq. They also discovered that the enemy was very close:

Day was breaking; however, no precise order was given, we stayed waiting in the village … What to do? No one knew. Our lieutenant, commanding the company, was the most affected by all this. He was completely incapable of giving any orders; turning from one group to another, stammering without uttering a coherent word. So finally we took the initiative ourselves, for the sun which was starting to light the crest of the hill reminded us that at any minute this hole of a village could become our tomb. So my section, with sergeant Vernhet in command, decided to leave the village.

They took up a position on the hills behind the village, hidden as best they could, waiting for the attack:

To think we were going to engage combat in these conditions against motorised vehicles, without a hole to shelter in, without any installation, while for four months we had modernised, prepared our trenches, which snaked between the blockhouses and the fortified positions, with reserves of food, telephone, blankets, nothing missing. To have abandoned all that to engage combat in the open fields, without shelter, without trenches, only a few kilometres from our trenches on the other side of the Meuse.… The sun was disappearing behind the hill and we thought that the moment was going to arrive; everyone was ready, the finger on the trigger, to fire at the first sight of the enemy.… Night fell and we had the joy, the great joy, of at last seeing the first French plane turning above the hills at a very low altitude. It was certainly welcome, the first one since the start of the fight, displaying its tricolour emblem above us, while since the beginning we had seen thousands of German black crosses. It gave us our courage back … and there was almost an ovation which greeted it.

During the night their thirst became so bad that Folcher went down to the village to fill up their flasks at the fountain. A lieutenant arrived to inspect with a staff officer. He saw that the section was not commanded and issued orders. This improved the mood. But the next morning the men’s spirits fell again when instead of the enemy they saw the dreadful sight of soldiers fleeing in chaos past the village (among them presumably Lesort, not in flight, but in search of his battalion).

They told us terrible things, unbelievable things.… Some had come from as far as the Albert Canal.… They asked for something to eat and drink; poor lads! … The stream went on endlessly; it was a piteous sight. Ah, if those enthusiasts who go and watch the magnificent military parades in Paris or elsewhere, could have seen on that morning this other army, the real one, not the army of parades and music, perhaps they would understand the real suffering of the soldier.

Soon afterwards, in the afternoon, the enemy assault began:

On the fringe of the wood, to the left and the right of the road, the first tanks made their appearance in large numbers. Our artillery redoubled its fire, concentrating everything now on one side, now on the other. Two tanks are hit and burn, a mortar shell scores a direct hit on a third and that also bursts into flames. The others, facing this violent barrage, turn and shelter in the forest. It is here that the scene changes. The enemy artillery comes into play and a hail of bullets starts to rain down. Too long to begin with, they burst behind us, but the range soon adjusts so that they rain down on us. I make myself small, as small as possible in my trench. Some fall so near that the trench trembles and the earth starts to collapse. It calms down a little and I stick my nose outside and spot a large tank, coming from I don’t know where, which is going to arrive right at the cross-roads in my field of fire. What can I do? Quickly I take out my normal magazine which I replace with one of our armoured bullets and I wait for the precise moment when it is going to come onto the cross-roads. I am not too confident as to what is going to happen, for I realise, and this is what makes me tremble, that if I miss, this formidable machine, spitting fire from everywhere, will come right over me, and we shall be lost. I also know that even armoured bullets don’t do very much harm to it. All this races through my head in an instant. In spite of this I’m still cool, and just at the moment when I’m going to let loose my first volley, a shell bursts on its front; immediately the engine stops and two men get off the vehicle. Half a minute later, some men from the platoon nearby take them prisoner without any resistance. It is a 25mm anti-tank gun, placed behind me and with the same line of fire as me, which stopped it. He really made me pleased, above all in not missing, for I had the impression that I was for it.

Despite this lucky escape, by the early hours of the morning it was clear that things were going very badly.

Suddenly a lieutenant, I don’t know which, and without any previous order, gives out a kind of ‘every man for himself’ directive. In five minutes, he announces, the withdrawal must have got over the hill. It’s abrupt and immediately there is a general panic, everyone thinking of his own skin.

Folcher got away to fight another day, until finally he was taken prisoner in June.38

These two narratives tell similar stories. They describe the experiences of two small detachments of soldiers trying to hold together and respond to the most adverse conditions while everything seems to be disintegrating around them. They show the terrifying impact of the German air superiority, the alternating waves of hope and despair, the soldiers’ sense of being thrown into a conflict for which they were not prepared, and the importance of leadership for men who found themselves isolated and cut off from their commanders.

Ultimately it is impossible to generalize about the performance of the French army in 1940. Certainly, in general it was the B divisions that performed least satisfactorily, but even here considerable differences are observable as one looks below divisional level. It seems impossible to relate these differences to the social composition or geographical origin of different units. One should be wary of accepting the contemporary prejudices of the French High Command, often repeated by historians, which view ‘sturdy’ Norman or Breton peasants as more reliable than soldiers of urban, especially Parisian, origin—just as in 1914 there were similar myths about the unreliability of troops from Provence—although it does seem that in 1940 North African—especially Moroccan—troops fought particularly well.