THE experience of Sergeant François Mitterrand in June 1940 was typical of that of many soldiers. During the Phoney War his unit, the 23rd Colonial Infantry Regiment, was stationed first in Alsace and then behind the Ardennes. Mitterrand found the boredom of the Phoney War deeply frustrating, and hated being a soldier. He lacked motivation and felt no commitment to the war. In a letter dating from the beginning of 1940, he wrote: ‘[W]hat would really annoy me is dying for values in which I do not believe.’ Once the fighting started, his unit, which managed to hold together, was forced to retreat towards Verdun. It was near Verdun, on 14 June, that Mitterrand was wounded by a shell. He was carried off on a stretcher along a road teeming with refugees. The refugee column was attacked by German planes, and the stretcher-bearers ran off, leaving Mitterrand lying on the road looking up at the German planes in the sky above him. Over the next five days, as the French armies retreated, he was taken from military hospital to military hospital. In the fifth of these, near Bruyères in the Vosges, he woke up one morning to find that the Germans had arrived, and he was now a prisoner. Later Mitterrand wrote of these days: ‘I was a defeated soldier in a dishonoured army, and I felt bitter towards those who had made that possible, the politicians of the Third Republic.’1

Mitterrand was transported to a prisoner-of-war camp near Kassel in Hesse. On his third attempt, he succeeded in escaping from the camp, arriving back in France in January 1942. He found employment as a functionary of the Vichy regime, working for the reintegration of prisoners of war who had been released from captivity. Gradually he gravitated from support for the Vichy regime towards active sympathy with the Resistance. By 1944 he was the leader of a Resistance movement of escaped prisoners of war.

Of all his experiences between 1940 and 1944, it was the defeat and imprisonment that had most marked Mitterrand. He claimed, in words rather similar to those of Sartre writing about his own imprisonment, that it was in the prisoner-of-war camp that he had his ‘first real encounter with other men’. It helped him to move away from the aesthetic individualism that had characterized his adolescence. About the defeat, he later wrote: ‘My sense of belonging to a great people (great in the idea that it constructed of the world and of itself, and of itself in the world, according to a system of values that rested neither on numbers nor brute force nor money) had taken some knocks. I had lived through 1940: no need to say more.’2 As much as anything, it is the words ‘no need to say more’ that deserve attention. As the historian Stanley Hoffmann has observed: ‘[T]here is a stunning contrast between the proportions of the May–June 1940 catastrophe and the role it plays in the country’s intellectual production.’3 There seems to be no equivalent of what the historian Henry Rousso, in his book tracing the memory of Vichy in French national life since 1945, has described as the ‘Vichy syndrome’—in political debate, in fiction, in films, and so on. A similar study of the defeat of 1940 would be rather short. In literature, the most notable works are the last volume of Jean-Paul Sartre’s Roads to Freedom trilogy, which opens with the defeat, the novel The Flanders Road (1960) by Claude Simon, and the novel A Balcony in the Forest (1958) by Julien Gracq. There is also a powerful description of the retreat from Dunkirk in Robert Merle’s novel Weekend à Zuydcoote (1972). Among films, there is really only Rene Clément’s Jeux Interdits [Forbidden Games] (1952), which tells the story of a small girl who loses her parents in the Exodus during a German bombing raid. A peasant family takes her in, and she and the little boy of the family create a secret animal cemetery. Although their macabre and disturbing activities are presumably supposed to reflect the impact on two children of the national trauma, the film is really about childhood more than it is about the defeat—apart from the extraordinarily vivid images of the Exodus in the first half hour.

Perhaps one reason for the absence of a ‘1940 syndrome’ is the long shadow cast by the ‘Vichy syndrome’. The defeat was immediately followed by a series of harrowing new experiences—occupation, collaboration, deportation—which pushed defeat into the background. At the trial of Pétain, which was supposedly about his role in the signing of the armistice and the end of the Republic—that is the events of 1940—the discussion frequently strayed into the Occupation period. Who had said what to whom at Bordeaux in the last days of June seemed in 1945 to belong almost to another era. It interested people less than what had happened after 1940. Similarly the parliamentary committee established in 1947 to look at the events in France between 1934 and 1940 never attracted much public attention.

Obviously no nation wishes to dwell on its defeats. In 1945, the shame of defeat seemed to have been partially redeemed by the heroism of the Resistance—even if many fewer people had been involved in the Resistance than had fought in the army in 1940. Of course, some, like Mitterrand, who had fought in 1940, later participated in the Resistance. But many of the soldiers of 1940 were unable to do so because they spent the war in prison camps. When these prisoners returned in 1945, they soon felt that they were somewhat unwelcome spectres at the feast of Liberation and national self-congratulation. After the initial celebrations to mark their return, they found that their memories of the war jarred uneasily with the general mood. France after the Liberation needed heroes, not reminders of defeat. As one of the prisoners’ newspapers put it: ‘[O]fficial France has forgotten you. A veil has even been thrown over those who died in 1940. France is ashamed of you.… Soon France will spit on your tombs.’ The soldiers of 1940 found themselves ignored by the Resistance and despised by the surviving veterans of 1914–18. One former prisoner recalled: ‘[T]hese were men who were so humiliated that they spent their lives trying to wash away the stain of their humiliation.’ Spokesmen for the former prisoners argued that the soldiers of 1940 had fought well but had found themselves in an impossible position. They also tried to link their role in 1940 to the subsequent emergence of the Resistance:

The prisoners must not have the feeling that … in the eyes of the country they are the defeated ones while others gather the laurels of victory. For, if it is true that France has never ceased to be at war … then the war is indivisible … and it is only fair that those who succumbed in the first act of the drama take their rightful place in its final act.4

This reading of the war as a single unity meshed with de Gaulle’s own interpretation of it. At the Liberation, de Gaulle, whose priority was national unity, hoped to put the occupation and the Vichy period in parentheses, and downplay those aspects of the occupation that had set the French against each other. De Gaulle argued that there had been an uninterrupted struggle of the French people against the Germans since 1940. Indeed de Gaulle went further, claiming that the war of 1939–45 was part of a thirty-year struggle between France and Germany that had begun in 1914. In this view, 1940 was a temporary setback in an ultimately successful conflict. All this might have made de Gaulle sympathetic to the plight of the prisoners of war. But it did not. De Gaulle had himself spent three years of the First World War as a prisoner. His five escape attempts had been unsuccessful, and he subsequently felt only shame and frustration about having been forcibly kept out of the action. De Gaulle’s view in 1945 was that the prisoners would do better to keep quiet, rather than draw attention to themselves. On hearing about Mitterrand’s Resistance movement of former prisoners, he allegedly remarked: ‘a Resistance movement of prisoners? Why not a Resistance movement of hairdressers?’ From the start de Gaulle’s relations with Mitterrand were extremely frosty. When Mitterrand came to lobby on behalf of the returned prisoners in June 1945, he received short shrift. Perhaps Mitterrand’s long-standing—and fully reciprocated—animosity towards de Gaulle derived in part from the different outlooks of two men towards their imprisonment—one of them resenting every minute that he had spent as a prisoner, and wanted in no way to dwell on the experience; the other of them counting it the formative experience of his life.

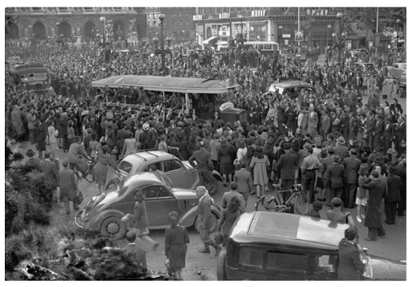

27. Crowds turn out on 1 June 1945 to greet the return of the millionth prisoner of war, Sergeant Jules Caron from Sisteron in the Basses Alpes. But once the welcome-home celebrations were over, the returned prisoners soon felt neglected and marginalized in post-war French society

If 1940 figures less prominently in France’s memory wars than one might expect, this may be because it was an event too painful to contemplate. One is reminded of Gambetta’s injunction about Alsace-Lorraine after 1870: ‘think of it always, talk of it never’. It is clear that the reverberations of the defeat have been profound and long-lasting. On the other hand, it would be wrong to see it as a kind of French Year Zero, and fall into the temptation of attributing to it all the major changes in France since 1945. Post hoc is not the same as propter hoc.

Of the defeat’s immediate consequences, however, there is no doubt. It was the precipitating cause of the collapse of the Third Republic and the setting up of the Vichy regime. And it set the agenda for Vichy’s ideological crusade to remake France. Pétain’s government, while still in Bordeaux, had signed an armistice with Germany on 22 June. According to its terms, France was divided into an Occupied Zone in the North, and along the Atlantic seaboard; and an Unoccupied Zone in the South. Since Bordeaux was, like Paris, situated in the Occupied Zone, the government took up quarters in the spa town of Vichy, whose numerous hotels provided ample accommodation for the ministers and their officials. The armistice said nothing about France’s internal political arrangements in the Unoccupied Zone, but it was inevitable that the Third Republic would not survive the defeat. Meeting in the Vichy casino on 9 July, Parliament voted almost unanimously to accept a proposal by Pierre Laval that the constitution should be revised. As Laval said: ‘[A] great disaster like this cannot leave intact the institutions which brought it about.’ On the next day, by a huge majority, Parliament voted to grant Marshal Pétain full powers to revise the constitution. Pétain almost immediately issued a number of constitutional acts which in effect gave him absolute power, and adjourned Parliament until further notice. The Vichy regime was born.

Many different political currents competed for power at Vichy, but all of them agreed on essentials. The new regime would be authoritarian and anti-democratic. The motto of the Republic—Liberty, Equality, Fraternity—was replaced by a new slogan: ‘Work, Family, Fatherland’. Vichy, then, represented the victory of the opponents of the Republic, whether those who had always hated it or those who had turned against it because of the Popular Front. After the defeat, the Bishop of Drax was heard to declare: ‘[T]he cursed year for us was not 1940, that of our external defeat, but 1936, that of our internal defeat.’ The triumph of the opponents of the Republic was, of course, only made possible by the defeat. On 28 May 1941, the economist Charles Rist noted in his diary: ‘Mme Auboin tells me that after the Armistice she received a letter from a reactionary friend of hers containing the words: “At last we have victory”.’5

The Vichy regime’s ideology was encapsulated in the phrase as the ‘National Revolution’. It claimed to replace the materialistic liberal individualism of the Republic with the traditional values of a hierarchical society structured around organic ‘natural’ communities such as the region, family, and workplace. It condemned class struggle, and celebrated the peasant and the artisan. It proclaimed the need to punish and persecute certain groups that were identified as the enemies of France: Jews, Communists, and Freemasons. The Vichy regime argued that the defeat had revealed the decadence of the political values of the Republic. Only days after Reynaud’s resignation Weygand had produced a memorandum setting down what he saw as the lessons of the defeat: ‘[T]he old order of things, a political regime made up of Masonic, capitalist and international ideas, has brought us where we stand. France has had enough of that.’ ‘We must not forget that we have been defeated and that every defeat has its price’, commented the Vichy leader Admiral Darlan in September 1940.

Much of the discourse of Vichy was built around the themes of guilt (for the sins of the past), suffering (in the defeat and Exodus), and redemption (through obedience to the Marshal and the National Revolution). As Pétain put it: ‘[T]he spirit of enjoyment has prevailed over the spirit of sacrifice.’ One Vichy propaganda documentary blamed the defeat on ‘the English weekend, American bars, Russian choirs, and Argentinean tangos’. The Church was particularly prone to this kind of language. As Archbishop Gerlier of Lyon put it: ‘[V]ictorious we would probably have remained prisoners of our errors.’ The Bishop of Toulouse was even more eloquent:

Have we suffered enough? Have we prayed enough? Have we repented for sixty years of national apostasy, sixty years during which the French spirit has suffered all the perversions of modern ideas … during which French morality has declined, during which anarchy has strangely developed.… For having chased God from the court, from the schools, from the nation, Lord we beg your forgiveness.6

In the immediate aftermath of defeat this kind of moralizing found a sympathetic hearing in the most unlikely quarters. André Gide, the author whose writing exemplified the kind of literature that Vichy judged immoral and decadent, criticized the ‘sorry reign of indulgence’ in his journal on 28 July 1940: ‘softness, surrender, relaxation in grace and ease, so many charming qualities that were to lead us blindfolded to defeat’. As Blum noted from his prison cell: ‘[F]rom the beginning of time national calamity has been linked with the idea of sin or error, and with its natural extension: contrition, expiation and redemption.’7

28. Vichy propaganda poster. On the left, Republican France undermined by democracy, speculation, anti-militarism, Freemasonry, Communism, pastis, bribery—with the Star of David floating above; on the right, Vichy’s new France built on solid foundations of Family, Work, Fatherland—with the seven stars of the Marshal floating above

Vichy rested, however, on more than political reaction and revenge. The huge crowds who turned out to cheer Pétain on his frequent tours around the country showed that he was genuinely popular. This popularity rested partly on his legendary reputation as the victor of Verdun, but his speeches in 1940 genuinely touched a chord among the French people. The certainties that he offered in 1940 had some appeal to a population traumatized by the defeat and Exodus. Uprooted from their homes and separated from their families—for months afterwards the newspapers contained poignant advertisements from people trying to trace children and relatives whom they had lost—millions of French people had witnessed in person the disintegration of the nation and the collapse of the State. Often the authorities had been among the first to flee. From his first speech as premier Pétain had expressed his compassion for the refugees. His language of rootedness and authority, family and security, resonated with a nation traumatized by its recent experience of upheaval and dislocation. The defeat, then, provided Vichy with its moral authority; it was the foundation myth of the regime. When the regime seemed to be losing its popularity Pétain was quick to remind the French what he had saved them from. ‘You have really short memories,’ he announced in June 1941, ‘remember the columns of refugees.’

Gradually Pétain used up the huge capital of goodwill that he had enjoyed in 1940 as the hardships of the Occupation pushed the sufferings of the defeat into the background. But what ultimately condemned Vichy to oblivion was its misreading of the international consequences of France’s defeat. Most Vichy leaders assumed that France’s defeat would soon be followed by a British surrender or defeat, and an end to the war. They had expected the armistice to be only the prelude to a peace treaty that would bring about a definitive settlement between France and Germany. Since the defeat of France seemed to ensure German hegemony over the European Continent, Vichy pursued a policy of ‘collaboration’ with its conqueror. In October 1940 Pétain met Hitler at the small town of Montoire-sur-le-Loire near Tours. He was photographed shaking Hitler’s hand, and after the meeting he declared that he was ‘entering upon the road of collaboration’. In 1941 the Vichy leader Admiral Darlan offered airbases to the Germans in the French colonial mandate of Syria. On one or two occasions the Vichy regime came to the brink of re-entering the war—this time on the side of Germany. This pro-German stance was partly driven by ideological affinity—Pierre Laval in June 1942 caused a sensation when he declared that he desired a German victory because it would represent the defeat of Russian Bolshevism—but even more by opportunism: Vichy believed that Germany had won the war. This judgement of course turned out to be Vichy’s biggest mistake.

Vichy’s narrow and Franco-centric view of the world failed to predict the massive consequences of the Fall of France for the future of the war. The war that had broken out in September 1939 had not been a world war but a European conflict involving France, Britain, Germany, and (briefly) Poland. It is at least possible that if the Allies had succeeded in holding off the initial German attack, a stalemate might have ensued, resulting in some kind of negotiated peace (it was not until January 1943 that the Allies adopted the principle of unconditional surrender). The Fall of France, however, transformed the international balance of power, sucking other powers into the conflict until by the end of 1941 the war had become a truly global one. De Gaulle had been right to proclaim from London that the Battle of France was only the first round in what would turn out to be a world war. The Fall of France was the end of the beginning, not the beginning of the end.

The consequences of the Fall of France for the war, and then the postwar course of international relations, were so dramatic that one historian has called it the ‘fulcrum of the twentieth century’.8 First off the mark to exploit the situation was Mussolini. Italy and Germany had been moving closer to each other since the later 1930s. On 18 March, Hitler and Mussolini had met at the Brenner Pass, and an Italian entry into the war seemed imminent. But Mussolini had not definitively burned his bridges with the democracies. He was urged against this course by his foreign minister, Count Ciano, and even more by the army Chief of Staff, Marshal Badoglio, who was only too aware of the inadequacies of the Italian armed forces. Badoglio told Mussolini that Italian intervention could only occur ‘if the enemy was so prostrated as to justify such audacity’.9 The startling German success in France seemed to have met this condition, and on 10 June Italy declared war on France. Mussolini’s late entry into the war won him a tiny zone of occupation in south-east France, but more importantly it opened up a new Mediterranean theatre.

This posed a great threat to the British. Having lost the support of the French fleet, and facing a hostile Italy, the British now had to commit an important part of their naval strength to the Mediterranean, at the price of leaving their Far Eastern interests dangerously vulnerable. On 28 June, the British government informed the Australian and New Zealand governments that it would not in the foreseeable future be able to send a fleet to defend Singapore. None of this was lost on Japan which, like Italy, had been moving closer to Germany in the 1930s without however breaking entirely with the West.10 Japan and Germany had signed an anti-Comintern Pact in November 1936, and there was a general desire among Japanese elites to expand Japanese influence in East Asia. This could only occur at the expense of the Western powers. But there were voices in the Japanese government urging caution, and these grew in influence at the end of 1939 after the signature of the Russo-German agreement. The defeat of France, however, shifted the argument back in favour of the pro-Axis camp. Quite apart from the increasing prestige of Germany and the weakening of British power in the Far East, the defeat of France also opened up a void in French Indo-China. In September Japan demanded free passage for its troops through Tonkin and the use of bases near Hanoi. The local representative of the Vichy regime, Admiral Decoux, had no choice but to accept, and Japanese troops moved into French Indo-China. On 27 September 1940, Germany, Italy, and Japan signed a Tripartite Pact in Berlin. The Fall of France had set in motion a radicalization of Japanese policy that was to lead in December 1941 to the fateful attack on America at Pearl Harbor.

While the German victory opened up possibilities and excited appetites in Italy and Japan, it caused corresponding alarm in Moscow. Stalin had been banking on a long conflict in the West, possibly ending in stalemate, certainly lasting long enough to allow the Soviet Union to build up its military strength. Now Hitler might turn against the Soviet Union at any moment. Stalin’s fears were entirely justified. The ink on the armistice agreement with France was hardly dry before Hitler had ordered his armed forces to begin preparing an attack on the Soviet Union for the next year. The extraordinary success of the German campaign in France meant that there was no resistance from the German High Command, as there had been to Hitler’s order to prepare an attack on France in 1939. The rapidity of the German victory had created a dangerous hubris among the German military, and on the part of Hitler himself a fatal conviction that he was a military genius who could never be wrong. This was to prove his ultimate undoing.

Stalin’s immediate response to the Fall of France was to annex the Baltic States on 15 and 16 June, and to seize Bessarabia and the Bukovina from Rumania on 26 June. These measures were accompanied by the decision to speed up rearmament. Stalin’s move into Bessarabia was intended to consolidate the Soviet position on the Black Sea littoral, and control of the mouth of the Danube. This worried Hitler, who saw the Balkans as a German sphere of interest, and it reinforced his conviction of the necessity to act against the Soviet Union as soon as possible. Thus were set in motion the decisions that would lead on 21 June 1941 to the German invasion of the Soviet Union.

The immediate reaction to the Fall of France by many British politicians was a kind of relief. Neville Chamberlain commented: ‘[W]e are at any rate free of the French who have been nothing but a liability to us.’ Lord Hankey, who had been chairing the now defunct committee on building up long-term Franco-British cooperation, wrote: ‘[I]n a way it is almost a relief to be thrown back on the resources of the Empire and of America.’11 Such comments revealed the pent-up resentment felt by many British observers at what was seen as France’s weakness and betrayal. But there was no doubting that British survival now depended more than ever on American support. As the Chiefs of Staff noted as early as 25 May, Britain would only be able to fight on alone if the United States was ‘willing to give us full economic and financial support, without which we do not think that we could continue the war with any chance of success’.

This required an important reorientation of British policy. Since 1919, Anglo-American relations had been far from cordial. The British had resented Wilson’s pretensions to influence the peace despite having entered the war so late. America’s refusal to cancel war debts was a running sore. In 1939, while hoping for American economic aid, the British remained wary of a greater American commitment. Chamberlain wrote in January 1940: ‘I don’t want the Americans to fight for us—we should have to pay too dearly for that if they had a right to be in on the peace terms.’ But four months later, on 19 May, Chamberlain wrote: ‘[O]ur only hope, it seems to me, lies in Roosevelt and the USA.’ Lord Halifax wrote to Hankey in July to tell him that the committee on Franco-British cooperation was now defunct and that ‘it may well be that instead of studying closer union with France, we shall find ourselves contemplating the possibility of some sort of special arrangement with the USA’. Winning the closer support of America now became the central objective of British policy. It corresponded also to the personal and ideological affinities of Churchill. What gave this strategy a good chance of success was the fact that the Fall of France had also caused a panic in Washington. Massive military spending bills were rushed through Congress, and over the next year Roosevelt edged closer to the British, bringing the country to the brink of war with Germany even before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.12

By the end of 1941, then, the European war had become a global one in which the massive power of America and the Soviet Union was soon to eclipse that of the other belligerents and lead inexorably to a new era of American—Soviet bipolarity after 1945. The Fall of France thus reveals itself in the medium term as a crucial moment in the eclipse of European power. Many of these developments would probably have occurred anyway. Even if France had remained in the war, it was likely that America would have joined the Allies ultimately. In that case America would certainly have emerged as the dominant force in the alliance. But without France the European balance in the alliance was dramatically weakened. The shift of British policy away from France also proved durable after 1945. In fact after the war there were those on both the British and French sides who hoped to rebuild closer links between the two countries. The French architects of the first stages of what was to become the Common Market certainly hoped to bring in the British, but by 1950 they had become convinced that this would not be possible. British ambivalence about European integration was certainly informed at some level by memories of 1940. The Fall of France helped to replace the Entente Cordiale, which had at some level informed British policy since 1904, by the Anglo-American ‘special relationship’ which has at some level informed it ever since.

No one was more aware of this development, and ready to draw what he believed to be the appropriate conclusions, than General de Gaulle. De Gaulle was fond of repeating a phrase that Churchill allegedly expressed to him in 1944 during one of their particularly stormy encounters: ‘[I]f I have to choose between Europe and the open sea, between you and Roosevelt, I will always choose America.’ The persistent suspicion that de Gaulle, and his successors, harboured towards the ‘Anglo-Saxons’ was born, to a considerable degree, out of the defeat. De Gaulle’s two vetoes of British entry into the Common Market, in 1963 and 1967, were partly inspired by his belief that Britain would act as a kind of American Trojan horse in Europe.

In many other ways also, Gaullism, the political movement that has so marked the history of post-war France, was born out of the Fall of France and the lessons de Gaulle drew from it. 1940 is the Year I of ‘Gaullism’, markedly de Gaulle’s first speech from London on 18 June. But de Gaulle already had a well-developed view of history by the time he arrived in London, and Gaullism resulted from the way he interpreted the events of 1940 in the light of his longer-term understanding of France’s history. De Gaulle was born in 1890, and his vision of the world was rooted in late nineteenth-century romantic nationalism. As he later wrote on the first page of his war memoirs: ‘[A]ll my life I have had a certain idea of France.’ The most fundamental conviction underlying that ‘idea’ was that ‘France cannot be France without greatness’. Unfortunately de Gaulle, whose generation lived still in the shadow of the defeat of 1870, was all too aware that France was not always ‘great’. He saw France’s history as a vast epic of alternating moments of grandeur and decline, light and shade, glory and tragedy. The defeat of 1940 fitted easily into this millennial scheme, and allowed him to relativize its long-term importance.

From the particular circumstances of that defeat—both its causes and immediate consequences—de Gaulle drew two conclusions that are crucial to the development of Gaullism as a political doctrine: first, the need for a strong state; second, the need to preserve national independence. Unlike the politicians of Vichy, de Gaulle did not spend much time discussing the causes of the defeat. Since he wanted to argue that France was still a great nation with a great future, it would have been somewhat counterproductive to dwell on its weaknesses. For Vichy, which was ready to accept a more diminished role for France, this was less of a problem. Nor did de Gaulle spend much time in recriminations against those responsible for the defeat. He made his reasons for this clear in a letter written in 1943 to the journalist André Geraud, who had just published under the pseudonym Pertinax a two-volume attack on what he called ‘The Gravediggers of France’. Géraud’s book indicted almost the entire political and military establishment of the Third Republic—Gamelin, Weygand, Daladier, Laval, and so on—but de Gaulle wrote that it was wrong to be too severe: ‘not that I deny their failure! But my feeling is that … [they] … suffered the effects of a deplorable general system that overwhelmed them. The fact is that it had become impossible truly to govern and to command in France because of the State’s chronic paralysis.’13 For de Gaulle, the most important fact about France’s defeat was the weakness of the State that had turned a military failure into a national catastrophe. His War Memoirs dispatched President Lebrun with lapidary brevity: ‘[A]s chief of state he had lacked two things: he was not a chief and there was no state.’

When he returned to France in 1944 as Head of the Provisional Government, de Gaulle had not yet worked out in detail what kind of constitutional arrangements would guarantee the kind of state he believed to be necessary. Thus, he missed the opportunity to impose his ideas while still enjoying unrivalled popularity. It was only after his resignation in January 1946 that de Gaulle unveiled his constitutional proposals which provided for a strong President and weaker Parliament. His proposals were ignored because they went too much against the grain of France’s Republican tradition. That tradition had emerged in the nineteenth century, in the shadow of Bonapartism, and was deeply suspicious of anything that smacked of authoritarianism. This suspicion had been reinforced by the recent experience of Vichy. Thus, the Fourth Republic, which emerged in 1947, was remarkably like its pre-1940 predecessor.

De Gaulle refused to have anything to do with this new Republic and set up a movement, the RPF, to advance his own ideas and bring about constitutional reform. The RPF was unsuccessful, and de Gaulle abandoned politics in 1953. But he finally had the chance to implement his proposals when he was called back to power in 1958 as a result of the crisis in Algeria. His new constitution was approved by a referendum in September 1958. The Fourth Republic was replaced by the Fifth, which still exists today. One of the most controversial provisions of the new constitution was Article 16, which allowed the President to assume emergency powers in case of crisis. De Gaulle himself applied this article in 1961 after an attempted army coup in Algeria. According to the Gaullist Michel Debré, the main architect of the new Constitution, de Gaulle insisted particularly on the importance of Article 16: ‘[H]e emphasized to us repeatedly that if the laws of 1875 [i.e. the constitution of the Third Republic] had provided for this right, President Lebrun would have decided to transfer the government to North Africa in June 1940 and France’s situation would have been entirely different.’14 After 1958, France, having had one of the weakest heads of state in Europe, was given one of the strongest.

The second moral that de Gaulle drew from the events of 1940 related to France’s position in the world. Already during the war de Gaulle had begun to look to the future. He told Jean Monnet in June 1943 that: ‘Anglo-Saxon domination in Europe was a growing threat and if it continued after the war France would have to turn to Germany or Russia.’15 De Gaulle’s entire foreign policy of the 1960s is contained in this sentence.

Another principle of foreign policy that de Gaulle derived from the Fall of France was the need as far as possible to conduct an independent foreign policy, and avoid dependence on any other power. This conviction was born partly out of the humiliating dependence of French policy on Britain in the 1930s, but even more out of de Gaulle’s own experience in London during the war. For a man of de Gaulle’s temperament and pride, it is almost impossible to measure the depths of humiliation he must have suffered through what he had witnessed in 1940 and through his complete dependence on the goodwill of the British. As one British observer (in fact Spears’s wife) noted in 1940:

He felt the dishonour of his country as few men can feel anything, as Christ according to the Christian faith took on himself the sins of the world. I think he was like a man, during these days, who had been skinned alive and that the slightest contact with friendly wellmeaning people got him on the raw to such an extent that he wanted to bite.… The discomfort that I felt in his presence was due, I am certain, to the boiling misery and hatred inside him.16

De Gaulle spent much of the war fuming against the real or imaginary slights suffered at the hands of his allies. He never forgot—or forgave—the fact that he had not been invited to the Yalta Conference of February 1945. The moral was that no nation should ever count on the support of any other, and it inspired de Gaulle’s decision to withdraw from NATO in 1966. It was for this reason also that de Gaulle gave prime importance to the development of a French nuclear weapon. He saw this as the only means by which smaller powers could achieve some semblance of equality with larger ones. In October 1945 he set up an Atomic Energy Commission (Commissariat à l’énergie Atomique: CEA) to develop atomic research and technology.

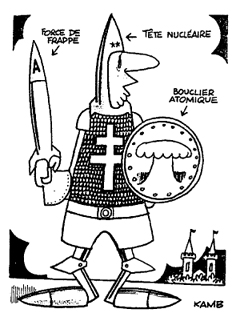

The explosion of France’s first atomic bomb over the Sahara on 12 February 1960 was hailed by de Gaulle, now back in power as President, as a great moment of national rejoicing. The satirical newspaper Le Canard enchainé mocked his enthusiasm: ‘this bomb has liberated France—what am I saying—it has liberated the French from a complex. It has liberated the old Gallic rooster that we all carry in our hearts and which hasn’t dared to show itself since 1940.… This bomb, oh dear Frenchmen, is the most beautiful day of our lives.17 Despite the opposition that de Gaulle’s nuclear policy aroused at the time, after his departure no government, of right or left, has challenged the necessity of France’s independent nuclear strike force (force de frappe). Implicitly they have accepted the logic of a speech made by de Gaulle immediately after the war: ‘Vanquished today by mechanical force, we can vanquish tomorrow with superior mechanical force.’

29. De Gaulle’s nuclear armour is mocked in the Communist La Nouvelle Vie Ouvrière on 8 January 1964. Wearing the Free French symbol, the cross of Lorraine, on his chain mail, he also has his ‘nuclear head’ [tête nucléaire], his ‘strike force’ [force de frappe], and his ‘atomic shield’ [bouclier atomique]

There is no doubt that de Gaulle’s achievement between 1958 and 1969 was an extraordinary one: he saved France from civil war, extricated it from Algeria, and provided ten years of unprecedented political stability and economic growth. Much of his legacy, so contested in his lifetime, has been untouched by his successors. But de Gaulle’s success as President also owed a lot to the achievements of the Fourth Republic, despite his portrayal of it as twelve wasted and disastrous years. Visiting French cities in the early 1960s he would sometimes affect surprise at the speed with which they had been rebuilt after the war, rather as if the Fourth Republic had not existed. In fact the Fourth Republic may not have given France political stability, but it did lay the foundations of what have been called the trente glorieuses, the almost thirty years of extraordinary economic growth France enjoyed up to the middle of the 1970s. The causes of that growth are a matter of dispute. Many factors played a part, including the general growth in world trade, Marshall Aid, productivity increases, and so on. But there are two important, perhaps decisive, factors, which can be directly related to the impact of 1940: first, the role played in post-war France by a new technocratic elite of administrators committed in an almost mystical way to the idea of economic modernization; second, the development of European unity.

Writing after France’s defeat in 1870, the philosopher Ernest Renan called on the French to undergo a complete intellectual overhaul. He commented that war was ‘one of the conditions of progress, the lashing that prevents a country from falling asleep, by forcing self-satisfied mediocrity out of its apathy’.18 In 1944, all political forces in France at the Liberation, divided on so many things, were united by the conviction that the defeat had revealed the profound mediocrity of France’s elites. Indeed some Resistance denunciations of France’s pre-war regime are all but indistinguishable from Vichyite ones. The Resistance saw itself as the new elite that would remake France, and overcome the decadence of the past. A key aspect of this analysis was the claim that France’s pre-war bourgeoisie had been too egoistical and inward-looking, and that its industrialists had been the slave of ‘Malthusian’ values—preferring prudence to risk, saving to investment. Since liberal capitalism in France had revealed itself as so inadequate, it was necessary for the state to step in and provide the necessary dynamism. The idea that economic liberalism must be replaced by ‘planning’ was shared to some degree by most of the forces of the Resistance.

This ambition was embodied in a number of institutions that were set up, or profoundly reformed, at the Liberation. The École Nationale d’Administration (ENA) [National Administration School] was set up to train the administrators necessary for the success of a modern state. The Centre National de Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) [National Centre for Scientific Research], which had been created on the eve of the war, was overhauled and given a central role in promoting research and offering scientific advice to governments. The Commissariat Général du Plan [Planning Commission] was established to plan reconstruction and economic modernization. The origin of the Planning Commission was a memorandum presented to de Gaulle by Jean Monnet, warning that France had the choice between economic modernization or decadence. If France did not choose modernization, Monnet said, it risked being reduced to the rank of Portugal or Spain, living on past glory. At the Planning Commission, Monnet gathered around himself a group of young economists and administrators, some of whom had spent the war in America or Britain, others of whom had been in the Resistance. All were animated by the same sense of urgency about the necessity of modernization. How important the Planning Commission was to post-war growth is difficult to calculate, but at the very least it played a major role in transforming the mentalities of industrialists and economic policymakers. The planners became the apostles of the new religion of growth.

1940 was not the only factor in the emergence of this new mentality. Proposals for planning and managing the economy more effectively had been in the air since the 1930s. The most exhaustive historical study of the transformation of French economic policymaking sees it as a cumulative process in which a part was played by the Popular Front and even by some of the policies of the Vichy regime. The setting up of the ENA in 1945 had first been proposed by Blum’s Popular Front government in 1936, but it had not managed to get the measure on the statute books. What made the defeat so important was that as a result of it the ‘modernizers’ became central to economic policy-making.

The second element that played a significant role in the success of the post-war French economy was the creation of the European Economic Community in 1957 after the signing of the Treaty of Rome. The origins of this go back to the beginning of Franco-German rapprochement in the late 1940s, and the setting up of the supranational Economic Coal and Steel Community between France, Germany, and four other countries in 1951. Here again the impact of the defeat was decisive, although of course there was no straight line leading from defeat in 1940 to reconciliation in 1950. It is true that some resisters were animated by a vague commitment to European federalism, but such ideas were never central to the Resistance, and their ideas had no influence on the policy of immediate post-war governments. On the contrary, in 1945 the whole idea of ‘Europe’ was somewhat tainted by its associations with Vichy, since many collaborators had claimed to be building a new ‘Europe’. The policy of France’s immediate post-war governments was not reconciliation with Germany but the destruction of German power once and for all. They wanted to break the country up and deprive it of the industrial powerhouse of the Ruhr. The unspoken assumption of Monnet’s first plan was that France could draw on German coal resources.

Only when it became clear that France’s former allies would not support such an approach to Germany did French governments decide to make a virtue of necessity and accept rapprochement with Germany. Since France could not destroy Germany, it had to find some way of living with it. The price of peaceful coexistence was that both countries would accept the need to sacrifice a degree of national sovereignty. This was the basis of the Coal and Steel Community. Even de Gaulle, so suspicious of any form of supranationalism, was pragmatic enough to accept and implement the Treaty of Rome when he returned to power in 1958. Later he made reconciliation with Germany one of the central planks of his foreign policy.

The lessons of 1940 did not all point in one direction. While France was committed to modernizing its economy, it was also dragged into an enormously costly and divisive series of colonial wars, first in Indo-China (1947–54) and then in Algeria (1954–62). There is no doubt that the process of decolonization in France was massively complicated by the legacy of 1940. In Britain, where the empire had traditionally loomed larger in the national consciousness, decolonization was considerably less traumatic. For many people in France after 1945, ‘Empire’ functioned as a sort of compensation for the humiliation of 1940. It represented all that was left of France’s claim to be a great power. Already in 1938, after Munich, many commentators had seized on the idea of the Empire as a way of softening the blow suffered by French prestige.

The significance of the Empire grew immeasurably after 1940. It was one of Vichy’s main assets, evidence that France still counted, even if half the mainland was occupied by the Germans. De Gaulle had also banked on the Empire, hoping that it would rally to him. In fact only French Equatorial Africa passed into the Gaullist camp in 1940, but even this gave de Gaulle a base of sorts outside London. Then in 1943, once the Allies had conquered North Africa from Vichy, de Gaulle was able to set up his government there. The whole Free French epic was intimately bound up with the Empire.

Few people believed that the Empire could continue unchanged after the upheavals of the war. There were endless discussions in 1945 about transforming the Empire into a so-called ‘French Union’. De Gaulle issued a famous call for reform in his 1944 ‘Brazzaville declaration’. But all these reforms were about finding ways to bind the colonial populations more closely to France, preserving the future of the Empire rather than preparing its demise. When the French army was defeated by the Vietnamese nationalists at the battle of Dien Bien Phu in 1954, the event was seen as a devastating humiliation (and just to underline the point, Paul Reynaud was a member of the government in power at the time). In some people’s minds this defeat only made it all the more urgent to hang on to French Algeria at almost any price. Algeria was the revenge for both 1940 and 1954.

By the mid-1950s, however, an increasing number of politicians, at both ends of the political spectrum, had started to question the viability of trying to hold on to the Empire. For such people Dien Bien Phu came almost as a relief, since it ended a war that was becoming ruinous for the country. As a result of the Indo-China war, between 1952 and 1954 military spending took up one-third of the budget, and represented a higher percentage of national revenue than it had even in 1938. Was it not becoming clear that, far from enhancing and augmenting French power, the Empire was in fact draining it, and acting as an obstacle to the economic modernization that was a much better guarantee of real power? By 1954 such ideas were sufficiently widely shared for the Prime Minister, Pierre Mendès France, to extricate France from Indo-China without much dissent.

The argument had to be fought out all over again when the Algerian war began in 1954. The withdrawal from Algeria was to be far more traumatic than the abandonment of Indo-China. This was partly because the territory was technically not a colony but part of France, and because there was a large European settler population. But the biggest problem in Algeria was the army, and here we return again to the legacy of 1940. The war had subtly affected France’s relationship with its army. After 1945 the army as a whole was no longer felt to represent the nation in the way that it had, despite the importance of pacifism, after 1918. Figures such as Foch and Pétain had been national heroes, almost demigods, and the prestige of the army had never been higher. After 1945, although the French army that de Gaulle reconstituted in North Africa had played an important role in the Italian campaign, the hero of the hour was the Resistance. The army emerged from the war partially detached from the nation.

Many of the post-war generation of professional soldiers who fought in the colonies had come into the army through the adventure of the Free French, which had emerged in revolt against the legal French state. Thus, these men were socialized into an army career whilst lacking the French army’s traditional respect for civilian authority. Their sense of alienation from the State was accentuated by years of fighting in Indo-China, far from France, and they were convinced that the politicians were letting them down. Where the image of the army in the inter-war years had centred upon the poilu, representative of the nation in arms, after 1945 it increasingly centred upon the paratrooper—member of a tough professional elite contemptuous of the softness of the civilian. In these circumstances it is easy to see how many soldiers in Algeria could feel that in rebelling against the French government they were being loyal to the true France, as de Gaulle had been when he rebelled against the government in 1940.

Twice the military in Algeria defied the government in Paris. On the first occasion, in May 1958, the result was to bring de Gaulle back to power. The second rebellion, in April 1961, was against de Gaulle himself once it was clear that he was preparing to give up Algeria. In the end, de Gaulle was able to ride out the military rebellion in Algeria precisely because these soldiers had become so disconnected from the nation that their defiance of the government in Algeria received no support from the mass of ordinary conscripts. Algeria acquired independence, and from that moment de Gaulle was free to pursue his wider foreign policy ambitions. Once de Gaulle had accepted Algerian independence in 1962, it is remarkable how quickly France seemed to adapt to a post-colonial existence. This was, of course, helped by the rapid economic growth of the 1960s, but also by de Gaulle’s skill at turning the process of modernization into a kind of epic adventure. In June 1960 he told the French: ‘[W]e must transform our old country of France into a new country, and it must marry its epoch.… France must become a great industrial state or resign itself to decline.’ 1940 was never explicitly mentioned in his many speeches on this theme, but the message was clear enough.

In the 1960s, then, France seemed finally to have put the defeat behind it. But it may be that the relative absence of references to 1940—compared to the ever more obsessive concern with Vichy—represented a refusal, or a reluctance, to confront the realities of declining French power (despite the successes of the trente glorieuses). This has become clearer in the years since de Gaulle’s death. At one level, Gaullism was about drawing lessons from 1940; at another it was about pretending that 1940 had not happened, or at least denying that it had any significant implications for France’s place in the world. France could—and indeed must—still be ‘great’ (de Gaulle’s favourite word). De Gaulle probably knew himself that this was not possible. Once he commented that he had written the ‘last pages of our greatness’. De Gaulle described his policy during the war as one of bluff, throwing dust in the Allies’ eyes so that they might be blinded into thinking that France still counted for more than it did. This is what he went on doing throughout the Fifth Republic, and because he was a prodigiously effective showman, he was remarkably successful. But the Gaullist conjuring trick could not last forever. After de Gaulle’s departure it became increasingly hard to sustain the illusion of French influence—partly because the economic crisis of the 1970s brought about an end to economic growth, partly because de Gaulle’s successors lacked his charisma. In the 1980s, the mood of France became extraordinarily pessimistic and inward-looking. There was much agonizing about threats to French identity and the dangers that globalization posed to French cultural ‘exceptionalism’. The success of the right-wing Front National in France since 1983 has certainly owed something to this ambient cultural pessimism. The Front’s appeal was partly built around a rhetoric of combating the imagined decadence of the French nation.

Perhaps, then, France is only facing up belatedly and obliquely to the full implications of 1940 for the place of France in the world. This book has, of course, sought to argue against some of the more ‘catastrophist’ interpretations of the Third Republic and against the idea that the defeat was unavoidable. But there is no doubt that the defeat was the military translation of a shift in the balance of world power away from France and Europe. The defeat of 1940 may not have been inevitable, but the longer-term decline of French power probably was. If this conclusion is right, it may follow that Gaullism drew quite inappropriate conclusions from 1940: it condemned a regime that had served France well in many respects, but refused to accept the geopolitical realities underlying France’s decline. The evident disillusion felt by much of the French population with its current political institutions suggests that de Gaulle’s vision of the State has less and less appeal. On the other hand, one could argue the contrary view: that despite the trauma of the memory of 1940, despite the somewhat exaggerated and superficial pessimism of the 1980s, the most striking feature of France in the second half of the twentieth century, after the terrible bloodletting of the First World War, has been its capacity for survival and reinvention, its resilience, the continuing attraction of its culture.

It is hard enough to understand the past, and historians should be modest about understanding the present, let alone trying to predict the future. The debate on the consequences of 1940 is surely still open. As the Chinese leader Chou En-lai once commented when he was asked in the 1960s to judge the consequences of the French Revolution: ‘it is too early to say’.