January 1940. Sir Edmund Ironside, Chief of the Imperial General Staff, summed up his impressions of the French army after a visit to France:

I must say that I saw nothing amiss with it on the surface. The Generals are all tried men, if a bit old from our view-point. None of them showed any lack of confidence. None of the liaison officers say that they have seen any lack of morale after the long wait they have had, after the excitement of mobilisation. I say to myself that we shall not know till the first clash comes. In 1914 there were many officers and men who failed but old Joffre handled the situation with great firmness. Will the Blitzkrieg when it comes allow us to rectify things if they are the same? I must say I don’t know. But I say to myself that we must have confidence in the French army. It is the only thing in which we can have confidence. Our own army is just a little one and we are dependent upon the French. We have not even the same fine army we had in 1914. All depends on the French army and we can do nothing about it.1

When Ironside wrote these cautious words, France and Britain had already been at war with Germany for just over three months, but there had been almost no fighting thus far. The Allies’ plan was to strangle the German war economy by imposing a blockade while meanwhile building up their own military strength. The intention was to mount an offensive in 1941 or 1942 once the British and French armies were fully prepared. If the Germans attacked in the meantime, the Allies had to be able to hold them off. The border between France and Germany was protected by the fortifications of the Maginot Line, but the French border with Belgium and Luxembourg was unprotected. Here almost everything would depend on the fighting quality of the French army.

On 10 May the Germans launched their offensive in the west, invading Holland, Belgium, and France. Holland capitulated in six days. On 13 May the Germans succeeded in crossing the River Meuse at Sedan, and forged ahead towards the Channel, threatening to cut off the British, French, and Belgian forces in Belgium. On 28 May, the Belgians surrendered. Between 26 May and 4 June, the bulk of the British forces were successfully evacuated from the French Channel port of Dunkirk before they could fall into German hands. There was now almost no British military presence left on the Continent. Now the Germans were free to turn south, into the heart of France. They broke through the French defences on the rivers Aisne and Somme. The French government evacuated Paris on 10 June, and the Germans arrived in the city four days later. On 22 June, the French government signed an armistice with Germany. In only six weeks the French had been defeated. This was the most humiliating military disaster in French history.

General Ironside’s questions about the French army seemed to have been answered with a finality that must have surpassed even his worst nightmares. In mid-June, one French observer, caught up in the huge wave of people fleeing south from Paris to escape the Germans, encountered a very different army from the one that Ironside had seen five months earlier:

I came upon some isolated soldiers, without arms, eyes cast down, their shoes scraping the grass at the road side. They avoided a cyclist, then brushed past a stationary car without seeming to see either of them. They walked like blind men, like dishevelled ghosts. Keeping apart from the peasants on their carts, from the city people in their cars … they moved on alone, like beggars who have even given up begging. We were witnessing the start of the rout, but we did not yet know it. We took them for laggards, we thought their regiments were far in front.2

The immediate consequences of the defeat were devastating for France. Half the country was occupied by German troops. In an unoccupied Zone in the south an authoritarian regime, with its capital at the spa town of Vichy, was set up under the leadership of the First World War hero Marshal Pétain. Democracy was dead in France. The country was liberated by the British and Americans in 1944 and a democratic Republic was set up again. But the trauma of the defeat of 1940 continued to mark the French people. In the words of the historian René Remond, who was a young man in 1940:

There is probably no more terrible trial for a people than the defeat of its armies: in the scale of crises, this is the supreme catastrophe. It scarcely matters whether one was formerly a pacifist or a militarist, whether one hated war or resigned oneself to it … defeat creates a deep and lasting traumatism in everyone. It wounds something essential in each of us: a certain confidence in life, a pride in oneself, an indispensable self-respect.3

The Fall of France was an event that resonated throughout the world. For Rebecca West, writing soon after the event, it was a tragedy that ‘ranks as supreme in history as Hamlet and Othello and King Lear rank in art’.4 As the New York Times observed a few days before the final French capitulation, Paris was seen throughout the world as ‘a stronghold of the human spirit … when Paris is bombed, the civilized world is bombed’. In Australia the Sydney Morning Herald proclaimed: ‘One of the lights of world civilisation is extinguished.’ On 19 June the Canadian Prime Minister, Mackenzie King, declared: ‘It is midnight in Europe.’ There was panic in Moscow, where Stalin was only too aware that the defeat of France made it possible for Hitler to turn his attention to the east. As Khrushchev recalled in his memoirs: ‘Stalin let fly with some choice Russian curses and said that now Hitler was sure to beat our brains in.’5 He was right. Hitler invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941. In the Far East, the collapse of French power created a power vacuum in the French colony of Indo-China, and excited the expansionist ambitions of Japan. In short, the defeat of France set in motion a massive escalation of the war: it helped to turn what had been so far a limited European conflict into a world war.

The rapidity and totality of France’s collapse has remained puzzling ever since. The British Foreign Secretary, Lord Halifax, wrote on 25 May 1940: ‘the mystery of what looks like the French failure is as great as ever. The one firm rock on which everybody had been willing to build for the last two years was the French Army, and the Germans walked through it like they did through the Poles.’ Later, in his memoirs, Halifax wrote that the Fall of France was an ‘event which at the time seemed something so unbelievable as to be almost surely unreal, and if not unreal then quite immeasurably catastrophic’.6 The French writer Antoine de Saint-Exupéry (author of the celebrated Little Prince), who was a pilot in 1940 and viewed much of the catastrophe from the air, begins his memoir of the events with the words: ‘Surely I must be dreaming.’7

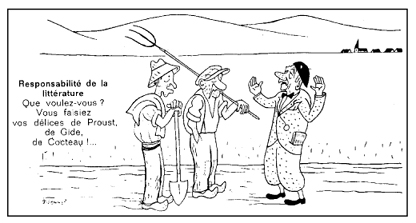

Within France the search for scapegoats began at once. The immediate aftermath of defeat saw the emergence of a whole literature of accusation and self-flagellation with titles such as The Gravediggers of France (by André Géraud), J’Accuse! The Men Who Betrayed France (by André Simon), The Truth about France (by Louis Lévy). One book, published in 1941, was even entitled Dieu a-t-il puni la France? [Has God Punished France?]. The answer was, of course, yes. Depending on ideological preference, people blamed politicians or generals, Communist agitators or Fascist fifth columnists, school-teachers or industrialists, the middle classes or the working classes. They blamed individualism, materialism, feminism, alcoholism, dénatalité, dechristianization, the break-up of the family, the decline of patriotism, treason, Malthusianism, immoral literature.

1. This 1941 cartoon mocks some of the more moralistic explanations for 1940. Two bemused French peasants are being told: ‘How can you be surprised [about the defeat]? You gorged yourselves on the works of Proust, Gide and Cocteau.’ All these writers shared in common the fact that they were homosexual.

The debate on the Fall of France has gone on ever since 1940, but now at least it is possible to view the event with greater serenity, and abandon the tone of polemic and accusation. That will be the purpose of this book: to tell the story of the defeat, explain why it occurred, and reflect on its consequences both for France and the world. The first part of the book provides a narrative of the defeat; the second part reflects on the causes, and the consequences, of that defeat in the light of the narrative that has gone before.

There are many strands to the Fall of France: it was a military defeat, the collapse of a political system, the breakdown of an alliance between two countries, and in its final stages, almost the complete disintegration of a society. Thus, each of the four narrative chapters in Part I will approach the events from a different angle. The first chapter looks at the military aspects of the defeat: French military doctrine, rearmament, the strategy of the High Command, the conduct of the military operations. The second looks at the relations between France and its allies: why France had so few allies in 1939, the way the British and French viewed each other, the way they cooperated during the fighting, and the relations between the leading personalities. The third looks at the political aspects of the defeat: the French political background, France’s political structures and leadership, the relations between the politicians and the military. The fourth chapter looks at the morale of the French people: French inter-war pacifism, the attitude of the French population towards the war, the training of the French army, and the way the soldiers fought once the Germans attacked.

In Part II we examine how these different narratives fit together. Is one of these four factors—military planning, allied relations, politics, morale—more important than any other? How are they related to each other? Was such a catastrophic defeat the indictment of an entire nation, or was it due merely to miscalculations by military leaders? Does an event of this magnitude necessarily have momentous causes stretching far back in French history? The answers to these questions will of course depend partly on the facts of the case; partly upon one’s own philosophical assumptions. The British military historian Basil Liddell Hart once wrote that ‘war is not a game which is won by sheer weight, but by the intelligence and finesse of its leaders’. Leo Tolstoy, on the other hand, famously believed that victory in a battle depended on massive historical forces outside the control of any individual. He scoffed at the idea that Napoleon had any control over events at the Battle of Borodino. This leads Tolstoy to the following conclusion: ‘[I]f in the descriptions given by historians we find their wars and battles carried out in accordance with previously formed plans, the only conclusion to be drawn is that these descriptions are false.’8 This pessimistic conclusion at least has the merit of reminding us that the smooth narratives of military history are prone to iron out the true messiness of battle. Tolstoy gives us Pierre Bezukhov wandering lost on the field of Borodino in search of a battle and finding only confusion; Stendhal gives us Fabrice del Dongo who only discovers subsequently that he has participated in the ‘Battle of Waterloo’. For this reason, I have tried in the narrative that follows to allow the ordinary soldier to be heard as well as the generals, the diplomats, and the politicians.