Theodor Seuss Geisel was born in 1904 in Springfield, Massachusetts.

A prosperous small city on the Connecticut River in western Massachusetts, Springfield boasted a Mulberry Street and Terwilliger and McElligot clans. Today there is a Dr. Seuss Room in the building that houses its New England Historical Society, and there are plans for a larger national memorial. Theodor was third-generation American, the second child and only son of one of the prosperous German-American families in Springfield. An older sister was born in 1902. On both sides of the family, his grandparents had emigrated to the United States from Germany. His father’s parents emigrated before 1870 and established a brewery in Springfield: Kalmbach and Geisel. The brewery became known as “Come back and guzzle.” The brewery prospered until Prohibition took effect in 1920 and killed it.

German was the language of the Geisel household. The family’s religion was Evangelical Lutheran, with services conducted in German. During World War I, Theodor, then a Boy Scout, sold U. S. war bonds. His grandfather, the immigrant Geisel, bought $1,000 worth. Theodor was one of ten Springfield Boy Scouts to win an award for successful sales.

After graduating from the Springfield public schools, Theodor enrolled at Dartmouth College, in the class of 1925. While still in high school, he had drawn cartoons, and at Dartmouth he gravitated to the college humor magazine. A run-in with the college authorities over bootleg liquor forced him to publish his cartoons under an alias, so he chose his middle name, Seuss (the German pronunciation of Seuss rhymes with Royce). The “Dr.” part came later. During his senior year, Theodor wrote to his father that he would get a college fellowship for postgraduate study at Oxford. His father boasted of this to the editor of the local paper, who mentioned it in print. The fellowship did not materialize, but, to preserve family pride, the elder Geisel footed the bill for the year at Oxford. That year convinced Theodor that academia was not for him. However, it exposed him to Great Britain, to France, and to Germany. The next year he spent in Paris, with trips to Switzerland, Austria, and Italy. “Dr. Seuss” never did earn a Ph.D., but when he became successful his alma mater conferred on him an honorary doctorate.

From 1927 to 1941 Dr. Seuss lived in New York City. He drew humor cartoons for an obscure humor magazine, Judge, which billed itself as “the world’s wittiest weekly,” and occasionally for more prestigious journals such as the Saturday Evening Post. One of his cartoons incorporated the bug-spray Flit, and it caught the eye of the wife of the advertising executive responsible for the account of Standard Oil of New Jersey, which manufactured Flit. For the next seventeen years Dr. Seuss was on the payroll of Esso (Ess-O, S[tandard] O[il of New Jersey]), earning the then-sizable income of $12,000 per year. So, during the Depression, when many Americans suffered severe financial hardship, Dr. Seuss did not. According to Dr. Seuss, “It wasn’t the greatest pay, but it covered my overhead so I could experiment with my drawings.” In a major break with his Republican father in 1932 he voted for Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Sometime after, Dr. Seuss moved to a spacious apartment at 1160 Park Avenue with a foyer, a large living room, a dining room, and two bedrooms.

The salary from Esso allowed for travel, both at home and abroad. On board ship returning from one trip to Europe, Dr. Seuss was struck by the rhythm of the ship’s engines. After landfall he produced the line, “And to think that I saw it on Mulberry Street.” It became the title of his first book. Twenty-seven publishers rejected the book before a Dartmouth acquaintance at Vanguard Press bumped into Dr. Seuss on a New York sidewalk. Vanguard published the book in 1937. In 1938, Vanguard published Dr. Seuss’s The Five Hundred Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins. After Vanguard merged with Random House, Random House published King’s Stilts (1939) and Horton Hatches the Egg (1940).

Fame and fortune did not come immediately. In its first six years Mulberry Street sold 32,000 copies. King’s Stilts sold fewer than 5,000 copies in year one and only 400 in year three. Horton Hatches the Egg sold 6,000 in year one and 1,600 in year two. The real takeoff in sales came in the years after the war. In 1957, Dr. Seuss published The Cat in the Hat, his breakthrough book. One source in 1959 puts Dr. Seuss’s cumulative sales at 1,500,000 copies; in 1979, the then-current total was 80,000,000; and today’s numbers are higher still. In any case, by 1941 Dr. Seuss had a steady income from Esso and the beginnings of a career as author of unconventional children’s books.

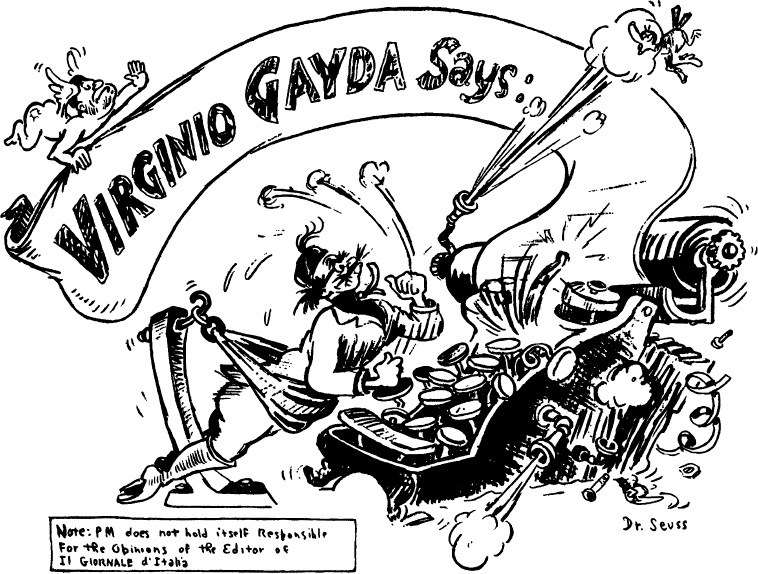

But all was not well with the world. In September 1931, Japan seized Manchuria, igniting Asia’s fifteen-year war. In September 1939, Germany invaded Poland and plunged Europe into six years of war. Dr. Seuss had strong views. His opposition to Italian fascism led him to set pen to paper for his first editorial cartoon. The cartoon exemplified the sharp wit, the wealth of detail, and many of the stylistic elements that were to characterize Dr. Seuss’s work for the next two years. In the cartoon, Virginio Gayda, editor of Il Giornale d’Italia, a major publication of the fascist regime, is suspended before a giant typewriter, banging away. He wears the fez that Italy’s fascist militia adopted for their uniform. Pieces of the typewriter fly off in several directions, and steam issues improbably from three vents. A steam typewriter? Who but Dr. Seuss could have imagined it? The steam does in the observer bird at top right (note the crosses for eyes, a sure sign that the bird is dead). As we shall see, onlooking birds and other creatures play important roles in Dr. Seuss’s wartime cartoons. The paper emerging from Gayda’s typewriter becomes a banner that extends back over his head, where a winged Mussolini holds up the free end. This is Dr. Seuss’s first version of Mussolini, but most of the elements we will see in later cartoons are already in place. The cartoon suggests that poisoned prose comes from this captive press: if Gayda is not captive, why can’t he stand on his own two feet?

Dr. Seuss showed it to a friend who worked for PM, a left-wing daily newspaper published in New York from 1940–1948. The friend passed it on to PM’s editor, Ralph Ingersoll, who liked it. The cartoon appeared at the end of January 1941. Below it was this note:

Dear Editor: If you were to ask me, which you haven’t, whom I consider the world’s most outstanding writer of fantasy, I would, of course, answer: “I am.” My second choice, however, is Virginio Gayda. The only difference is that the writings of Mr. Gayda give me a pain in the neck. This morning, the pain became too acute, and I had to do something about it. I suddenly realized that Mr. Gayda could be made into a journalistic asset, rather than a liability. Almost every day, in amongst the thousands of words that he spews forth, there are one or two sentences that, in their complete and obvious disregard of fact, epitomize the Fascist point of view. Such as his bombastically deft interpretation of a rout as a masterly stroke of tactical genius. He can crow and crawl better than any other writer living today. Anyhow...I had to do a picture of Gayda.

— Dr. Seuss

The editor added, in parentheses, “Dr. Seuss is a topflight advertising artist, most famous for his Flit cartoons.” With this cartoon, Dr. Seuss began his career at PM. In February and March, he published only three cartoons, all of them reactions to pronouncements by Gayda. But from late April on, Dr. Seuss published three or more cartoons each week. He worked as editorial cartoonist for PM from early 1941 to January 1943, nearly two full years, spanning months when the United States was at peace and months when it was very much at war.

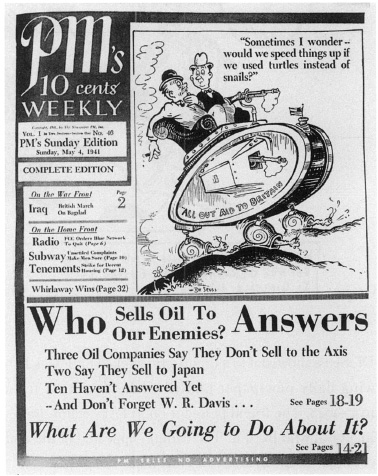

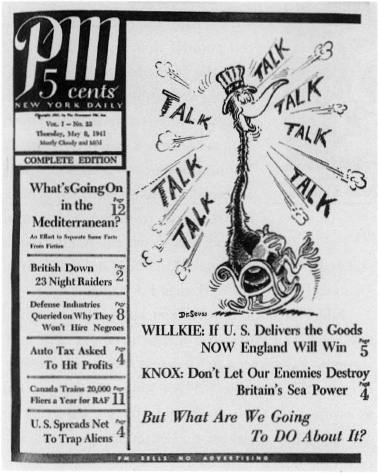

In his monograph on PM, Paul Milkman describes the paper as “A New Deal in Journalism;” the play on words is intentional. PM was a new deal in many ways. It cost five cents per copy when its competitors sold for two or three cents. It ran no comics (at least at first), crossword puzzles, or stock market reports. It specialized in photographs and other visuals using an improved “hot ink” printing process; the issue of November 26, 1942, for example, carried eight full pages of war maps, most of them full-page spreads and one of them a two-page spread. It accepted no advertising. It continued no stories onto back pages. It pioneered radio pages, the early equivalent of the newspaper television guides of today. It attracted some of the greatest names of the day in American journalism and letters. Erskine Caldwell, James Thurber, I. F. Stone, James Wechsler, Heywood Hale Broun, Lillian Hellman, and Jimmy Cannon: all wrote at one time for PM.

Most important, PM was outspoken in its politics. Ralph Ingersoll, a prominent journalist who had worked for Time and Life, was its founder and first editor, and he issued political position papers regularly. For example, this is one of his formulations of the PM stance: “We are against people who push other people around, just for the fun of pushing, whether they flourish in this country or abroad. We are against fraud and deceit and greed and cruelty and we seek to expose their practitioners. We are for people who are kindly and courageous and honest.... We propose to applaud those who seek constructively to improve the way men live together. We are American and we prefer democracy to any other form of government.” Or again: “The Fascist philosophy [represents] a live threat to everything we believe in, beginning with a democratic way of life.... We do not believe either the study of the works of Karl Marx or membership in the Communist Party in America is antisocial.”

On December 8, 1941, in the immediate aftermath of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Ingersoll sent a “Memo to the Staff” setting down “what [he] had to say” that day. It includes this section:

3. That with the declaration of war, PM’s first job was done. The first serious job that PM undertook was giving the people of America the facts about the threat of Fascist aggression—at home and abroad. When the Fascists attacked us yesterday, this job was finished. We have nothing more to say about the threat for it has now materialized in the open attack that we have been so long convinced was inevitable.

4. That this is our satisfaction: that our warnings have contributed to the preparedness of this country....

5. That today we begin a new task. That this task is WINNING THE WAR.

Ingersoll surely claimed too much for PM, both in preparing the United States for war and in winning the war, but such was his ambition and PM’s sense of mission. PM’s daily circulation was about 150,000. In those days there were seven other mass-circulation dailies in New York City, including the New York Times (daily circulation: roughly 500,000) and the Daily News (daily circulation: over 2,000,000). As we shall see, the latter paper was the particular target of PM’s outrage.

On January 6, 1941, Ingersoll had further thoughts:

At present our particular interests are:

FOR—ALL OUT PRODUCTION OF WEAPONS...that comes ahead of everything for our stake is human lives. (We always take Victory for granted; we work to speed victory to save lives.)

FOR—INTELLIGENT TRAINING OF OUR ARMED FORCES....

FOR—INTELLIGENT LEADERSHIP....

FOR—DEMOCRACY AT HOME. The war against Fascism continues at home as well as abroad. It is one war, wherever. At home we now wage it in the name of winning the war on the field of battle. The big word MORALE covers it—too much like a tent to suit us.... LABOR’S INTERESTS ARE SYNONYMOUS WITH OURS—AND WITH THE COUNTRY’S....

AGAINST—DEMOCRACY’S RECORDED ENEMIES. By the time the Fascists attacked Pearl Harbor and Hitler and Mussolini declared war on us, the Professional Isolationists had revealed themselves as American Enemies of Democracy.... We experienced hunters of American Enemies of Democracy have a special obligation—and privilege—to expose them. It takes doing. But we’ll find ways to do it.

PM signed on to the New Deal of President Roosevelt, but it did so—in the words of historian Paul Milkman—“at precisely the moment when Roosevelt was abandoning New Deal politics to create an interventionist coalition.” As the Administration moved toward the right, PM endorsed intervention but clung to the Administration’s earlier social commitments.

Michael Denning’s The Cultural Front speaks of the Popular Front of the 1930s and early 1940s, that coming together of industrial unionists, Communists, independent socialists, community activists, and emigré antifascists behind a three-part program: antifascism and anti-imperialist solidarity social democratic electoral politics and civil liberties. Writes Denning “The Popular Front emerged out of the crisis of 1929, and it remained the central popular democratic movement over the following three decades.” Among the intellectuals, it brought together older “patrician” modernists such as Malcolm Cowley and Edmund Wilson and younger “plebeian” writers and artists: producer John Houseman, filmmaker Fritz Lang, playwright Bertolt Brecht, writers Ayako Ishigaki and Franz Werfel, composers Kurt Weill and Béla Bartók. Denning labels PM “the Popular Front tabloid.”

Editor Ingersoll himself later had second and third thoughts about PM and its activism. This is clear from accounts of these years in his papers at Boston University. In one outline he wrote: “ ‘A New Kind of Newspaper’ was to have been A Crusade all right—but a crusade not for any political or social reform but simply against the stupidity, the dullness, the lack of imagination and ingenuity—and the occasional venality—of the Big Business American Newspapers of the Twentieth Century. If there were any politics in this, they were reactionary rather than radical. They sought to go back to simpler days when the newspaper business was not to sell advertising space but to tell news. This was the diametrical opposite of the concept of the propagandist. Yet PM had become the propagandist to end all propagandizing (and itself!).” To the last sentence Ingersoll appended in pencil: “—the warmonger of all times.” The date of this addition is not clear, but the insertion speaks eloquently to Ingersoll’s second thoughts.

For the years 1941 and 1942, Dr. Seuss drew editorial cartoons for PM. PM was on the left in American politics, but what defined the spectrum? What were the issues? Who were the players? Fifty-two percent of those Americans eligible to vote went to the polls in November 1940 to vote in the presidential election pitting President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, a Democrat elected first in 1932 and reelected in 1936, against Wendell Willkie, a Democrat-turned-Republican. The war in Europe and Asia was a major issue. Should the United States oppose the Germans and aid the British? How? To what extent? At what risk? Willkie supported Roosevelt’s foreign policy—aid for Britain—but attacked New Deal social programs. The result was Roosevelt’s third victory and an unprecedented third term, although Roosevelt’s margin of victory was much narrower than in either 1932 or 1936: Willkie won 22,000,000 votes to Roosevelt’s 27,000,000 and eighty-two votes in the electoral college (in 1936, the Republican candidate had won eight). What is more, Republicans held on to most of their striking gains of 1938 in the House. Roosevelt won the election in part by promising not to take the United States into the war.

However, in his State of the Union address (January 6, 1941) President Roosevelt called for “full support of all those resolute peoples everywhere, who are resisting aggression and are thereby keeping war away from our hemisphere,” and he spoke disparagingly of the noninterventionists: “We must always be wary of those who with sounding brass and a tinkling cymbal preach the ‘ism’ of appeasement. We must especially beware of that small group of selfish men who would clip the wings of the American eagle in order to feather their own nests.” Four days later he submitted to Congress a bill to allow shipments on credit to Britain and other nations fighting Germany. This was the Lend-Lease Act, which, somewhat amended, passed Congress late in March. The House vote was 260-165, with 135 of 159 Republicans voting no; and the Senate vote was sixty to thirty-one, with seventeen of twenty-seven Republicans voting no.

The rhetoric was heated, in part because this was a significant step away from neutrality, in part because the bill as submitted gave the President great power. Senator Clark of Missouri, a Democrat like the President, stated: “It is simply a bill to authorize the President to declare war...and to establish a totalitarian government.” Senator LaFollette of Wisconsin, a Progressive, called the bill “a bill for Congress to abdicate.” Socialist leader Norman Thomas derided it as “dictatorship in the name of defending democracy.” Roosevelt’s long-time antagonist Republican Representative Hamilton Fish of New York said: “It looks as if we are bringing Nazism, fascism, and dictatorship to America and setting up a Führer here.” Roosevelt did have the support of Wendell Willkie, who as defeated Presidential nominee could claim to speak for the Republican Party.

Where was the American public on the issue of war and peace? Public opinion polls show that from the start of the fighting in September 1939 the American public preferred a British to a German victory by an overwhelming margin, but by the same overwhelming margin the public opposed American entry into the war. Particularly after the fall of France in June 1940, a majority of the American public was willing to help the British cause by any means short of fighting. Germany’s military victories had increased public distaste for Hitler, but the public was not ready yet for war. Still, by 1941, when Dr. Seuss began drawing his editorial cartoons, the “isolationist” coalition had begun to fray badly.

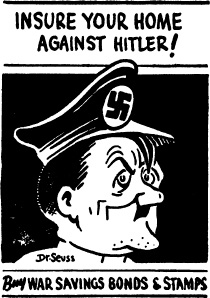

It was into this volatile picture that Dr. Seuss plunged. He joined forces with PM to produce the cartoons in this volume. After the initial few months, during which the cartoons appeared anywhere in PM’s twenty news pages, they appeared most often on the editorial page, usually as the only illustration on that page. Side by side with the signed editorials, the cartoons enjoyed a prominence of place exceeded only by the cover, and a half dozen PM covers themselves carry Dr. Seuss’s cartoons. Occasionally there are smaller Dr. Seuss drawings elsewhere, in among the letters to the editor or promoting the sale of war bonds. Two such signed drawings depict Hitler and “Japan.” A third, unsigned but clearly from the pen of Dr. Seuss, depicts the aftermath of the sinking of a German submarine.