![]()

THE EARLIEST CIVILIZATION TO HAVE LEFT WRITTEN RECORDS IS THE Sumerian culture that arose in the fertile crescent of ancient Mesopotamia between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. Although populated from early times, the area was first settled between 4500 and 4000 BCE by a people referred to as Ubaidian,1 who knew nothing of the local language but arrived from outside as a markedly civilizing influence. They drained the marshes, established agriculture, then created industries that included metalwork, leatherwork, masonry, pottery, and weaving. From this base, they developed a flourishing trade with neighboring regions.

But the people we now call Sumerian, whose tribal tongue became the prevailing language of the territory, did not arrive on the scene until 3300 BCE, probably from Anatolia. Within a few hundred years, the country had developed twelve separate city-states: Kish, Erech, Ur, Sippar, Akshak, Larak, Nippur, Adab, Umma, Lagash, Bad-tibira, and Larsa. Each comprised a walled city with its surrounding villages and land. Their earliest political system was a democracy of sorts, with power vested in the people. This gave way to a theocracy controlled by various independent groups of high priests, but growing rivalry between the states seems to have called for a more centralized form of authority so that one by one they each adopted the institution of kingship.2

There was, according to their written records, a universal belief in spirit beings. Each city had its patron god. In the early days of the civilization these numbered only ten—Anu, Enlil, Enki, Inanna, Ki, Nanna, Ningal, Ninlil, Ninurta, and Utu—but by 2000 BCE, the Sumerian pantheon had grown to some thirty-six hundred deities. However, we must not assume such belief was only a matter of religious faith. Julian Jaynes, a Princeton professor of psychology, has warned not to impose such a modern-day prejudice. Following a thorough study of the period, he was led to the astonishing conclusion that the ancient texts should be taken literally: not only did the spirits speak, but their voices were heard by entire urban populations.3 In a carefully reasoned thesis, Jaynes presents a wealth of compelling evidence to suggest that whole civilizations were founded and functioned on the orders of these preternatural entities. They were, he claims, far more intrusive even than they are today, taking on visible form and directing the actions of a humanity that functioned at a level little better than an army of robots. We were, at that time, literal playthings of the gods, utterly unable to disobey their edicts or resist their plans.

Jaynes, who died in 1997, was the son of a Massachusetts minister. He studied at Harvard and McGill, received a doctorate (in psychology) from Yale, and lectured at some twelve other universities including Princeton and Cornell. In 1976, he dropped a bombshell on the academic world with his publication of a work later described by the prominent Darwinist Richard Dawkins as “one of those books that is either complete rubbish or a work of consummate genius, nothing in between.”4 The book in question groaned under the unwieldy title of The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind, but read, in many respects, like an intellectual thriller. In it, Professor Jaynes argued that prior to about 1250 BCE—a date that permits the establishment of several ancient civilizations—the whole of humanity was guided by spirit voices. No medium was involved. These voices manifested to everyone with apparent objectivity, sometimes accompanied by materializations—or at least visionary experiences—and were accepted as instructions from the gods.

Jaynes’s starting point was the Iliad, Homer’s epic poem chronicling the events of the Trojan War and itself one of the oldest extant works of Western literature. His initial analysis of the document revealed something strange. The heroes of the Iliad all seemed, without exception, to be in constant communication with their gods—and almost incapable of taking any action that did not spring from divine instructions.

The characters of the Iliad do not sit down and think out what to do … When Agamemnon … robs Achilles of his mistress, it is a god that grasps Achilles by his yellow hair and warns him not to strike Agamemnon. It is a god who then rises out of the gray sea and consoles him in his tears of wrath on the beach by his black ships, a god who whispers low to Helen to sweep her heart with homesick longing, a god who hides Paris in a mist in front of the attacking Menelaus, a god who tells Glaucus to take bronze for gold, a god who leads the armies into battle, who speaks to each soldier at the turning points, who debates and teaches Hector what he must do, who urges the soldiers on or defeats them … It is the gods who start quarrels among men that really cause the war, and then plan its strategy. It is one god who makes Achilles promise not to go into battle, another who urges him to go and another who then clothes him in a golden fire reaching up to heaven and screams through his throat across the bloodied trench of the Trojans, rousing in them ungovernable panic … The beginnings of action … are in the actions and speeches of gods … When … Achilles reminds Agamemnon of how he robbed him of his mistress, the king of men declares, “Not I was the cause of this act, but Zeus.”5

To most modern readers, of course, the gods are no more than a poetic invention, a device intended to render the narrative more vivid and interesting. But the events of the Iliad are already both vivid and interesting. The poem is about action and the action is constant. There is no need to “cut to the chase”; in the Iliad the “chase” is all there is. Any further poetic device, any invocation of fictional gods, is patently unnecessary. Yet there it is, in line after line of the epic. More to the point, it is integral to the work itself. Both the Iliad’s author and the Iliadic characters are agreed in their acceptance of a divinely managed world. Faced with these puzzles, Jaynes took the courageous step of considering the possibility that the gods of the Iliad were not poetic inventions at all, but a wholly accurate account of the world as it was at the time of the Trojan War. What if, he speculated, both Greeks and Trojans really were listening to mysterious voices and sometimes looking on the very faces of their gods? What if it was all true, exactly as the Iliad described it? In such circumstances, “to say the gods are an artistic apparatus is the same kind of thing as to say that Joan of Arc told the Inquisition about her voices merely to make it all vivid to those who were about to condemn her.”6

From this starting point, Jaynes went in search of further evidence that the world of our early ancestors may have been quite different from the world we experience today. He speculated that the earliest form of universal spirit contact occurred simultaneously with the development of urban living around 9000 BCE. A study of the Natufian settlement of Eynan, some twelve miles north of the Sea of Galilee, showed a town of more than two hundred people supported partly by hunting and partly by a primitive form of agriculture, with a social structure based on the rule of a king. The king’s tomb at this site was a circular edifice some sixteen feet in diameter housing two complete skeletons. One wore a shell headdress and was presumed to be the king’s wife. The other, the king himself, was partly covered in stones and partly propped upright, with his cradled head facing the distant Mount Hermon. The entire grave was surrounded by a wall, painted in red ocher, supporting a roof of large flat stones. On this roof, the Natufians had built a hearth, surrounded by a second wall, again roofed with stone slabs. Topping the entire structure were three large stones set central and surrounded by a ring of smaller ones.

Primitive though it was, this curious edifice has a religious feel about it, like the stupas found beside Himalayan roadways. Jaynes speculates that this is precisely what it was—a device that allowed the dead king to issue commands in spirit form, as he had done during life. When a holy fire was lit in the ceremonial hearth, its smoke, “rising into visibility for furlongs around, was, like the gray mists of the Aegean for Achilles, a source of … the commands that controlled the Mesolithic world of Eynan.” This, says Jaynes, was the paradigm of what was to happen over the next eight millennia. The spirit of the dead king was transformed, in the imagination of the Eynans, into a god. The king’s tomb was the god’s house, the precursor of far more elaborate god houses and temples to be erected in the years ahead. Even the two-tiered formation of its structure was prescient of the multitiered ziggurats of temples built on temples (as at the ancient Sumerian city of Eridu) and the gigantic pyramids at Giza in Egypt.

Given that the plain people of Eynan heard the spirit voice of their dead king, their living king, his successor—who was also privy to the words of the spirit—would naturally designate himself as the dead god-king’s priest or servant, thus ensuring his own authority until death permitted him to join with his predecessor as a god in his own right. Once established, this pattern spread throughout Mesopotamia and was particularly evident in ancient Egypt. As it did so, the tomb was gradually replaced by the temple (which contained no burial remains) while a statue took the place of the corpse—metaphors that continued to function admirably as an aid to spirit communication.

Jaynes spread his archaeological net and discovered that the basic plan for human group habitation from the end of the Mesolithic to relatively recent times was a god-house (temple or church) surrounded by man-houses. As cities expanded to embrace thousands of souls, so the god-houses became monumental, culminating in structures so large that they became the focus of spirit communication for miles around. He came across actual depictions of such communication. Two stone reliefs from an ancient site in Guatemala, for example, depicted a man prostrate on the grass as he was lectured by two divine figures. One clearly represents Death, the other is half human, half deer. Jaynes notes7 that to this day the local chilans (prophetic shamans) adopt an identical posture for their peyote-enhanced conversations with spirits.

He discovered too that, as the centuries progressed, the tombs of kings, priests, politicians—indeed all who could afford it—were gradually filled up with grave goods … and even servants. The kings of Ur, for example, ruling during the first half of the third millennium BCE, were entombed with their entire retinues, often buried alive in a crouched position as if ready to spring up to offer service. The tombs also contained copious supplies of food, drink, clothing, weapons, jewelry, musical instruments, and even draft animals yoked to ornate chariots. Clearly these goods were assumed to be of use to the deceased. Jaynes further discovered that the burial of important personages as if they were still alive was common to almost all of the ancient cultures he surveyed. Nor was this bewildering custom confined to the rich and powerful. In Sumerian Lagash (now modern Tell al-Hiba) in about 2500 BCE, a commoner was buried with seven jars of beer, 420 loaves, two measures of grain, one garment, a head support, and a bed. The excavation of graves from the Indus civilizations of India revealed fifteen to twenty food pots per person. Similar finds were discovered in the Neolithic Yang-Shao cultures of China, not to mention the Olmec and Mayan kingdoms of South America.

This practice has no clear explanation except that their voices were still being heard by the living and were perhaps demanding such accommodation.8

The lengths to which the living would go in order to placate the voices they heard is illustrated by the fact that some early Greek graves had feeding tubes that allowed broth to be poured down into the rotting mouths of the corpses below. Even more macabre is the painting on a mixing bowl dated to 850 BCE and now in the Metropolitan Museum in New York. This vessel depicts a boy tearing his hair with one hand while he stuffs food into the mouth of his mother’s corpse with the other. To Jaynes, this was yet another indication that spirit voices had convinced the populace that the dead, despite appearances, lived on.

The advent of writing provided further support for Jaynes’s contention that spirits of the dead were thought of as gods. An Assyrian incantation text makes the connection overtly. In it, the dead are referred to directly as ilani or gods. Records of the Aztec civilization quote the ancients as believing that when a man died he became a god—so much so that the expression “he has become a god” was used as a euphemism for death.

Alongside the grave goods and written traditions, Jaynes noted a veritable explosion in the use of figurines and life-size images during the millennia following the Eynan burial. The function of such figurines has been something of an archaeological mystery, with the most popular theory suggesting that they were fertility charms. Jaynes dismissed this idea as failing under logical analysis. Fertility charms would be of little use in areas where fertility was never a problem. Yet they were found in great numbers in such areas. Since many of these were stood upright in tombs, he took them to be more permanent substitutes for the propped corpse. Their function, he suggested, was to trigger the phenomenon of the spirit voices.

Jaynes found support for this conclusion in the figures themselves. Those of the Olmec civilization, to give only a single example, were created with open mouths and exaggerated ears, suggesting they had something to do with verbal communication. There was also the curious, and almost worldwide, convention of figures with exaggerated, staring eyes. Sometimes this was achieved by enlarging the eyes, sometimes by the use of rock crystal or gemstone inserts. Thousands of figures dating to about 3000 BCE, found in the upper branches of the Euphrates, had heads that consisted almost entirely of eyes enhanced with malachite paint. Analysis shows the diameter of the human eye is approximately one tenth the height of the human head, a measurement Jaynes elected to refer to as an eye index of one. His investigations showed that ancient statuary of gods had eye indexes as high as 18 and 20: “huge globular eyes hypnotically staring out of the unrecorded past of 5,000 years ago with defiant authority.” The choice of the word hypnotically is deliberate. Jaynes became convinced that for our faithful ancestors, staring into the hypnotic eyes of their carved gods facilitated the state of mind in which they could more easily hear the sound of spirit voices. How can we know that such idols “spoke”? Jaynes asks rhetorically, then answers:

A Harvard professor has argued that statues like this Olmec figurine once ‘spoke’ directly to worshippers.

I have tried to suggest that the very existence of statuary and figurines requires an explanation in a way that has not previously been perceived … The setting up of such idols in religious places, the exaggerated eyes in the early stages of every civilization, the practice of inserting gems of brilliant sorts into the eye sockets of several civilizations, an elaborate ritual for the opening of the mouth for new statues in the two most important early civilizations … all these present a pattern of evidence at least.9

It is a pattern of evidence supported by the fact that cuneiform texts often refer to statues speaking while, closer to hand for most readers, the Old Testament tells how the king of Babylon “consulted with images” (Ezekiel 21:21). In South America, Aztecs told their Spanish conquerors that their history began when a statue from an ancient ruined temple spoke to their leaders, while nearby Peru was considered by the Spanish to be a kingdom commanded by the Devil, because Satan himself spoke to the Incas out of the mouths of their statues:

It was commonly in the night they entered backward to their idoll and so went bending their bodies and head, after an uglie manner, and so they consulted with him. The answer he made was commonly like unto a fearefull hissing, or to a gnashing which did terrifie them; and all that he did advertise or command them was but the way to their perdition and ruine.10

It was evidence of this type that led Julian Jaynes to conclude these and similar statues were not of a god but were themselves the god.

He had his own house … [which] formed the center of a complex of temple buildings, varying in size with the importance of the god and the wealth of the city. The god was probably made of wood to be light enough to be carried about on the shoulders of priests. His face was inlaid with precious metals and jewels. He was clothed in dazzling raiment and usually resided on a pedestal in a niche in the central chamber of his house … Since the divine statue was the owner of the land and the people were his tenants, the first duty of the steward-king was to serve the god not only in the administration of the god’s estates, but also in more personal ways. The gods, according to cuneiform texts, liked eating and drinking, music and dancing; they required beds to sleep in and for enjoying sex with other god-statues on connubial visits from time to time; they had to be washed and dressed and appeased with pleasant odors; they had to be taken out for drives on state occasions; and all these things were done with increasing ceremony and ritual as time went on … The divine statues also had to be kept in good temper. This was called “appeasing the liver” of the gods and consisted in offerings of butter, fat, honey, sweetmeats placed on the table as with regular food … How is all this possible, continuing as it did in some form for thousands of years as the central focus of life unless we posit that the human beings heard the statues speak to them, even as the heroes of the Iliad heard their gods or Joan of Arc heard hers? And indeed had to hear them speak to know what to do.11

The social structure, as Jaynes conceived it, was complex. The common people were not privy to the words of the great gods who ruled from their ziggurats and temples. But even the lowliest commoner had his or her own gods embodied in idols or figurines living in household shrines. They too demanded their daily rituals and offerings, usually modest versions of the temple ceremonial. They too spoke to the citizens who served them and issued orders about what should be done and by whom. If, faced by some particularly fearful crisis or hugely important decision, a commoner wished to speak with one of the great civic gods, he could not do so directly but had to consult his personal house deity to act as an intermediary. Cuneiform tablets depict the practice, showing a great god seated while a lesser deity conducts the petitioner into the divine presence. The whole thing is somewhat reminiscent of later ideas about “guardian angels”—which might themselves be distorted memories of the earlier experience. In one sense, all spirit/god contact was personal. Every man and woman was capable of hearing the voice of her own deity. But the deities themselves formed a strict hierarchy, each answering to another, so that an important question or message could filter upward until it reached the city’s great protector, who would then advise his personal servant—the king—on what should be done about it.

It was a structure that survived for millennia, but, manifestly, not indefinitely. Clearly, not everyone today is capable of hearing spirit voices—indeed, a sizeable proportion of the general population does not even believe in them. Jaynes realized that if his conclusions were correct, there was an age during which spirit intercourse with humanity increased to such a degree that it was all but universal, but that age eventually ended. He reasoned that for his theory to stand up, he had to find the point in history where things changed, the point when the gods withdrew and spirits ceased to speak directly to anyone who cared to listen. Consequently, he began to search for the turning point.

Jaynes was aware of the problems that could—indeed must—arise in any society whose members were constantly directed by spirit voices. As populations increased, so did the complexities of life … and the odds in favor of the spirits issuing contradictory orders. Once such contradictions reached critical mass, the basic structure of the society would collapse. Evidence of this was, he believed, writ large in the pre-Columbian civilizations of America where, time and again, whole populations suddenly deserted their cities to adopt a tribal lifestyle in the surrounding jungle. Such mass desertions, with no apparent cause, have remained a mystery to orthodox archaeology but were seen by Jaynes as a necessary flight from spirit instructions that no longer made any sense or had ceased to produce satisfactory results. This explanation also fitted an even more mysterious observation—the fact that given time, usually a century or more, there was often a drift back to the deserted cities, sustainable until the population once more increased to unmanageable proportions.

The linkage between population density and cultural collapse seemed to be confirmed by texts like the Sumerian epic Atrahasis, which opens with the words:

The people became numerous

The god was depressed by their uproar

Enlil heard their noise

He exclaimed to the great gods

The noise of mankind has become burdensome.12

Interestingly, this text approaches the problem not from the viewpoint of a burgeoning population, but from that of the spirits themselves. And the spirits, it appeared, were not best pleased by the tendency of their worshippers to “be fruitful and multiply.” The epic goes on to describe how they visited plagues, famines, and, eventually, a great flood on their followers in a brutal attempt to reduce population numbers. Clearly, whatever else may have been happening, the structure of the spirit-driven society was breaking down. By the end of the third millennium BCE, the problem was becoming increasingly evident. In Egypt, for example, the final century of this millennium saw the sudden, total breakdown of all authority. People fled the towns in an exodus reminiscent of the South American cities, brother fought brother, nobles scratched for food in the fields, children slaughtered their parents, tombs and pyramids were ransacked.

Orthodox historians postulate that the cause must have been some great natural disaster, without, however, being able to support their theory with hard evidence. Nor was there evidence of natural disasters in similar periodic breakdowns of the Mayan civilization mentioned earlier, or the collapse of Assur around 1700 BCE. But as we shall see shortly, natural disasters did hasten (but not cause) the population-generated breakdown in other areas. So did a wholly unexpected element, the invention of writing.

One of the founding fathers of modern psychology, Carl Gustav Jung, somewhere mentions the numinous quality of archetypes, a natural tendency to generate feelings of awe in those who encounter them. The same numinosity clings to spirits, as I witnessed some years ago when a medium agreed for the first time to publicly channel a spirit she introduced as an ancient Egyptian god. Her forty-strong audience consisted largely of professional people and included a judge, a medical doctor, a physicist, several academics, and an engineer. The medium fell into trance and the spirit entity spoke through her to deliver a brief address followed by a request for questions. None were forthcoming, but several members of the audience stood up to pledge themselves to the service of the god, despite the fact that, in our rational age, no one had asked for proofs or bona fides. Most people have a tendency to make unquestioned assumptions about the powers and authority of spirits, even when the communicating entities made no such claims for themselves. When a spirit requires something to be done, one feels an urge to carry out its wishes; and while it is perfectly possible to disobey, it feels uncomfortable to do so. If these observations represent the atrophied remnants of ancestral responses, it is easy to imagine the impact of a spirit command in the cultural context of a listener in, say, 4000 BCE, but only if the command was delivered directly.

The deserted city of Palenque, in South America, was just one of those abandoned, for no apparent reason, at the height of their power.

Writing seems to have been developed in early societies as a means of keeping track of trade negotiations and possessions, but its scope was quickly extended to record city ordinances and countrywide legislation, both of which had, of course, come from the mouths of the gods. But if a law laid down face-to-face by a deity was virtually impossible to disobey, the same numinousness did not attach to the same law in written form. Writing was a convenience and, like most conveniences, spread very quickly through any culture that developed it. Soon it became the prime carrier of the wishes of the gods and, in so doing, weakened them.

The historical context of the final breakdown, which Jaynes eventually pinpointed to the second millennium BCE, was spectacular:

[The era] was heavy laden with profound and irreversible changes. Vast geological catastrophes occurred. Civilizations perished. Half the world’s population became refugees. And wars, previously sporadic, came with hastening and ferocious frequency as this important millennium hunched itself sickly into its dark and bloody close.13

The volcanic eruption at Thera, now firmly placed midway through this millennium, is one of the more striking examples of what Jaynes is talking about here. The Aegean island, some sixty-eight miles north of Crete, exploded with such violence that an estimated twenty-four cubic miles of material was thrown up into the atmosphere, darkening the sky for days and influencing the climate of the whole Northern Hemisphere for years. Nor were the consequences purely local. Climatic effects included crop failures in China. The immediate shock waves were equivalent to the simultaneous detonation of more than thirty H-bombs.14 After the explosion, the population of Thera itself was obliterated and only a fraction of the island remained above water. A 490-foot-high tsunami devastated the northern coast of Crete, smashing two miles inland at 350 miles an hour to destroy the infrastructure of kingdom after kingdom.14

The disaster triggered a series of mass migrations and invasions that brought down both Hittite and Mycenaean empires. As the remnants of the old societies, with their different languages and customs, were forced to intermingle, what guidance could the spirits offer in the face of such overwhelming chaos? Their voices failed and, without divine guidance, humanity promptly made matters worse by embarking on wars of previously unimaginable brutality. The Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser I staked whole populations alive from groin to shoulder and established a rule of law that amounted to what scholars of a later age would refer to as a “policy of frightfulness.”15 The chaos spread throughout the Mediterranean and the known world. Conflict and brutality took hold on a scale unknown throughout the preceding eight millennia. But these miserable developments were not the only change afoot.

![]()

Sometime around 1230 BCE, the Assyrian king Tukulti-Ninurta I commissioned a stone altar that bore his own likeness … twice. The first image is of a standing figure. In the second, the tyrant is on his knees before the throne of his god. This is an extraordinary representation, quite unlike earlier versions of the same scene. In these, invariably, the king would stand tall, locked eye to eye with the deity as he listened to its words. At no time, in the millennia-long history of spirit communication, did he kneel. More astonishing still, the throne before which Tukulti-Ninurta prostrates himself is empty. The god has gone.

In modern times we have become so accustomed to the idea of an invisible god that it is difficult to comprehend how shocking this representation really was. In tablet after tablet, altar stone after altar stone, cylinder after cylinder, the god was always depicted as an heroic humanoid figure, standing or sitting. Why then in Tukulti’s reign is the god missing from this and other altars? Why, suddenly, was he represented by an abstract symbol on the cylinder seals? For Julian Jaynes there was no mystery at all. These scenes depicted reality as our Assyrian ancestors of the time experienced it. And the reality was that their god no longer appeared to them; their god no longer spoke.

Here at last was the turning point Jaynes had been looking for. In ancient Mesopotamia the spirits became silent at some point between the time of Hammurabi (died 1750 BCE), who was frequently depicted communing with his god, and that of Tukulti (1243–1207 BCE), whose deity seemed to have deserted him. Jaynes cast about for confirmation and discovered there were three clay tablets from the time of Tukulti that completely endorsed his conclusions. They were inscribed by a feudal lord named Shubshi-Meshre-Shakkan who began a sorry tale of woe with the words:

My god has forsaken me and disappeared

My goddess has failed me and keeps at a distance

The good angel who walked beside me has departed.16

The disappearance of this lord’s guardian spirits was only the beginning of his misfortunes. Without their guidance, he quarreled with Tukulti and consequently lost his position as ruler of a city. He fell prey to sickness and other misfortunes. He tried prayer, prostrations, and sacrifices, he consulted priests, but nothing brought the spirits back. (Interestingly, however, they did appear eventually in his dreams to assure him he had been forgiven his offenses and would henceforth prosper—the significance of which will become apparent later in this book.)

The change that was taking place was gradual, extending over some hundreds of years and moving at its own pace in different locations. Jaynes charts its progress as he analyzed it out from scores of ancient texts, scrolls, carvings, and tablets. The ancient hierarchical structure that flourished throughout the third millennium BCE permitted your personal god (with whom you communicated daily) to intercede with your city’s god and even, in times of great emergency or need, with the kingdom’s chief god, who generally communicated only with the king. Such intercessions were depicted in carving after carving showing the humble petitioner being presented to the great god by a lesser (personal) deity. But by the middle of the second millennium BCE the scenes change. As typified on Tukulti’s altar stone, the major gods begin to disappear. Personal gods are seen presenting supplicants not to the ruling deity but only to his symbol. Then, by about the end of the second millennium BCE, there are changes in the representation of the personal god. He, or she, was no longer the purely humanoid deity he used to be but had in many cases metamorphosed into a bizarre half-human, half-avian creature.

Sometimes this new entity appeared as a winged man, reminiscent, in all but artistic style, of later depictions of angels. Sometimes it might appear as a bird-headed human, like the ibis-headed figure of Thoth in the ancient Egyptian pantheon. Sometimes it was a winged bull or lion. In the early stages of the change, such entities appear in presentation scenes, introducing the individual to the symbol of a major god. Later, however, such scenes disappear from the record altogether and the hybrid entities usually appear only as guardians, sometimes of places, sometimes of people, sometimes of kings. Each representation appears to have one thing in common: in no case do the entities speak. The spirits may still appear, but they remain strictly silent. Texts from the period show the reaction of whole populations to the change. There is general consternation and bewilderment. Why have our gods abandoned us? What have we done wrong?

Jaynes is quick to note that in these two archetypal questions lie the roots of the great themes found in every major religion of our modern world. Christ’s last cry on the cross—My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?17—is answered not by God but by the great accusation of the Christian church, Because humanity has sinned! Nor, it transpired, could any penance or sacrifice atone for the mysterious transgression. When the father of history, the Greek author Herodotus, climbed the steps of the Etemenanki ziggurat in Babylon almost a thousand pleading, prayerful years after the time of Tukulti, he hoped to find a statue at the top, but there was only an empty throne.

As a psychologist, Professor Jaynes had his own theories about spirit contact that shall be examined in a later section of this book. But for the moment, his work is important in that it permits us to build up an intriguing, if somewhat puzzling, historical picture. If Jaynes’s deductions are correct, that picture, in summary, is this:

At some point in deep prehistory, more (and possibly much more) than thirty thousand years ago, while humanity led a primitive, difficult, hunter-gather existence, certain individuals of the tribes became aware of spirit contacts and eventually developed techniques, some involving plant narcotics, that allowed them access to the spirit worlds. These individuals, whom we now refer to as shamans, believed they could rely on spirit advice in matters of healing and the location of game, both life-and-death essentials in the rigors of an Ice Age. Their consequent practice as doctors and prophets brought them prestige and a position within their tribe rivaling that of the chief himself. They formed primitive “guilds” to protect the secrets of their craft and adopted initiatory tests and rituals in their selection of candidates who wished to become shamans in their turn. Their work was of such importance to the tribe that (so many modern anthropologists believe) it was commemorated in cave art.

Throughout this whole period, the relationship between shaman and spirit might be characterized as one of cautious respect. Shamans found spirits often helpful, often reliable, but sometimes dangerous and occasionally untruthful. Although spirits could and would sometimes compel action, particularly in the matter of a tribesperson becoming a shaman in the first place, they were never, in any real sense, the masters. But nor were the shamans, whose title “master of the spirits” denoted no more than a skill at making contact and extracting direct assistance or useful information. Nobody actually commanded anybody. Instead, there was, generally speaking, a partnership based on mutual respect.

This situation remained essentially unchanged for tens of thousands of years and appears to have been beneficial to hunter-gatherer communities. But, if Julian Jaynes’s patient detective work is correct, something happened approximately ten thousand years ago that marked a transformation—the gradual shift from hunter-gathering to farming, the move away from nomadic to urban lifestyle and larger communities. Whether this shift was prompted by spirit advice or simply a natural, evolutionary development, we have no means of knowing. But the shift itself certainly coincided—if we accept a literal interpretation of the archaeological evidence—with a new form of spirit communication. No longer was the shaman required. No longer were individuals forced to face life-threatening trials to contact spirit worlds. For reasons not yet clearly understood, the spirits stepped forward from their ancient domains and became accessible to entire human populations.

With this change came another: the traditional relationship between human and spirit quickly broke down. No longer was there an equality based on mutual respect. The spirits became masters and something in the new relationship persuaded us to accept the change with the submissiveness of sheep. When a spirit issued orders, some deep-seated instinct compelled people to obey like automata. But the dictatorship proved benevolent. Spirit decrees enabled happy, fulfilled lives, free from any serious degree of conflict. Under spirit leadership, towns became cities, trade developed with other spirit-guided cultures, bellies and purses were full. In gratitude, humans transformed the spirit contacts into gods and offered them worship as well as obedience. It was, in many respects, a golden age and is recalled as such in world mythologies.

The situation remained essentially static for millennia before a further change occurred. A gradual population increase reached critical mass and the hierarchical structure established by the gods could no longer support it. Spirit communications became confused, then counterproductive. Spirit advice could no longer be counted on to produce benevolent results. Society gradually descended into chaos and the day eventually arrived when the spirits themselves began to withdraw. This process too was gradual. Like the shamans of old, there were still some people who could see and hear the spirits, but for the majority, the gods first fell silent, then changed into lesser creatures, and eventually disappeared altogether.

For thousands of years every god had a specific terrestrial location as a statue in a temple or an idol in the home. Now the statues were silent and the idols lifeless lumps of wood or stone. Where had the spirits gone? Humanity supplied its own answer by deciding their deities had retreated into the sky, an identification with heaven (the ultimate home of the gods) that holds good to the present day. A new relationship began, based on unanswered prayers, individual isolation, and distant memories of a time when the gods had real immediacy and power.

But inevitably, there was a gradual adjustment to the new status quo. The priesthood became guardian of social custom, cultural tradition, and religious ritual. Each priest was looked on as a medium channeling cosmic forces, another way of saying that the powers of the gods flowed through him, but the majority asked for their powers to be accepted on faith. Their congregations believed them because belief was more comfortable than complete abandonment.

On a different level, the massive body of Mesopotamian magical texts, much of it concerned with divining the will of the gods or directly seeking their advice, suggests a widespread wish to communicate in the old style that was certainly not confined to the priesthood. Superstition and theological theory rushed in to fill the emotional vacuum. Sumerians came to believe in a gloomy afterlife inhabited by the souls of the dead and were not averse to attempting postmortem contact with their ancestors if they thought it might be beneficial. Enlil, one of whose titles was “Lord of the Land of Ghosts,” was said to have gifted humanity with spells and incantations to compel the obedience of spirits, good and evil; and there were those who sought to use the gift to practical effect. Even more common were texts devoted to celestial observation and astrological lore, which attempted to discern the influences emanating from the highest spirit realms on human affairs.18 But much of this is speculation. For more detailed information on how early civilization adjusted to the change—and established a new and different form of contact with its gods—we need to move away from Mesopotamia to examine another ancient culture whose copious, well-examined records will give us a clearer picture.

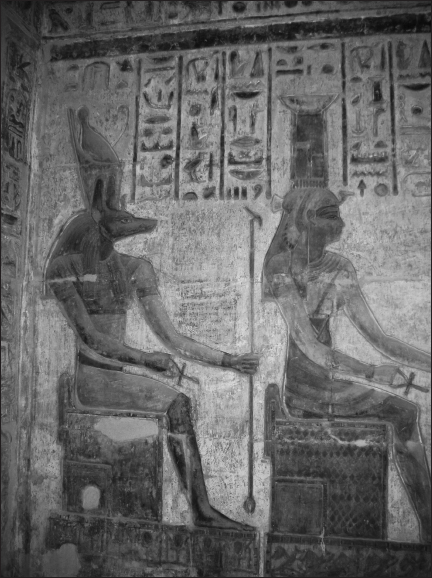

The jackal-headed god Anubis (left) was believed to communicate with the citizens of ancient Egypt.