![]()

ACCORDING TO PLINY THE YOUNGER, ROME’S FAMOUS LAWYER, author, and magistrate:

There was at Athens a mansion … of evil repute and dangerous to health. In the dead of night … a specter used to appear, an ancient man sinking with emaciation and squalor, with a long beard and bristly hair, wearing shackles on his legs and fetters on his hands … Hence the inmates, by reason of their fears, passed miserable and horrible nights in sleeplessness … The mansion was accordingly … abandoned to the dreadful ghost.

However, it was advertised … [and] … Athenodorus the philosopher … read the advertisement. When he had been informed of the terms, which were so low as to appear suspicious, he made inquiries, and learned the whole of the particulars. Yet … did he rent the house.

As evening began to draw on … the shaking of irons and the clanking of chains was heard, yet he never raised his eyes … The noise … approached: now it seemed to be heard at the door, and next inside the door. He looked round, beheld and recognized the figure he had been told of … and followed it. It moved with a slow step … and after turning into the courtyard of the house vanished suddenly and left his company.

On being thus left to himself, he marked the spot with some grass and leaves which he plucked.

Next day he applied to the magistrates, and urged them to have the spot in question dug up. There were found there some bones attached to and intermingled with fetters; the body to which they had belonged, rotted away by time and the soil, had abandoned them thus naked and corroded to the chains. They were collected and interred at the public expense, and the house was ever afterward free from the spirit, which had obtained due sepulture.

The above story I believe on the strength of those who affirm it.1

In this account, Athenodorus’s practical, down-to-earth approach to the ghost reflects his culture. Ancient Greece was populated by an expansive pantheon of divinities who, while theoretically resident on the distant peaks of Mount Olympus, were intimately involved in every aspect of human life. The supreme deity, Zeus, guarded the home, ensured the sanctity of oaths, protected storehouses and supplicants, insisted on the gift of hospitality to strangers, and brought justice and safeguarded the city, among a host of other duties. His lesser companions took over where he left off: Eros was in charge of love, Selene governed the moon, Demeter protected agriculture, and so on, almost endlessly, so that spirit intervention was accepted as a rule of nature and a fact of life.

Scholarly analysis suggests classical Greek religion emerged from a blending of Cretan goddess worship and, later, more masculine elements personified in the mighty Zeus himself. But the roots run both deeper and wider than that. Any study of the subject will reveal an uneven, but clearly recognizable, development from primitive magical practice to official state religion. The progression extends from a type of nature worship where spirits were thought to animate the wind and the waters, to a more sophisticated religious expression in which the gods appeared in human form. Yet even at its most developed, the magical element remained, most noticeably visible in popular cults that simply associated natural forces, flora, and fauna with specific gods and goddesses. Overall, religious expression in classical Greece was an amalgamation of early Aegean and later Indo-European elements, with the former including Minoan and Mycenean survivals dating back to the Bronze Age. Against such a background, it comes as little surprise to discover evidence of widespread spirit contact. Among the most intriguing sources were the Greek Mysteries.

Although often referred to as a religion, the Mysteries were actually an induced religious experience. Tradition has it they were founded by Orpheus, the legendary singer who charmed beasts, birds, rocks, rivers, and trees with voice and lyre. Ancient genealogies date him to a time prior to the thirteenth century BCE, but scholarly investigation is content to fix a later date, somewhere in the fifth or sixth century BCE, which saw the emergence of Orphic groups dedicated to a life of purity, with dietary restrictions and sexual abstinence. The similarity to shamanism has been noted and shamanism is accepted as one of the roots of Orphism. Its main expression, in those early days, was its staunch support of the individual, leaving one free to choose whatever form of worship he or she wished—a novel idea at the time. There is some suggestion of spirit contact, notably in the activities of the priest-prophet Pythagoras, who around 500 BCE, seems to have channeled Orpheus in some of his writings. He certainly attributed portions of his own work to Orpheus without, however, establishing any satisfactory historical provenance. The emphasis within Orphism on “Orphic” poetry, with its traditional evocation of the Muse—herself a spirit creature—is another small pointer in the same direction. But the prime manifestation was in the Mysteries themselves.

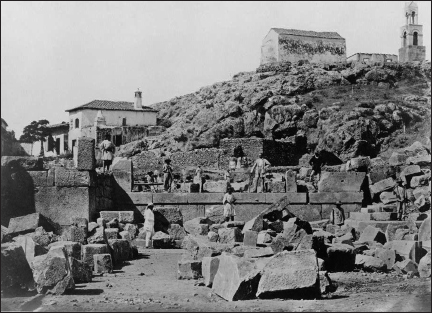

The ruins of Eleusis, which was once the heart of a religion that held out the promise of direct spirit contact.

Historically, the first location of the ritual Mysteries was the small Greek town of Eleusis, a coastal city on the Isthmus of Corinth, between Athens and Megara. Ceremonies were held there in honor of the goddess Demeter. Among them were local initiations of town burgesses, in rites that were more political than religious and strictly confined to Eleusinian townspeople. But the practice underwent a profound change when Eleusis was annexed by Athens around 600 BCE. This meant Athenians were now entitled to initiation and many of them claimed the right. Greeks from other areas soon began to follow suit.

At about this time, there was a change in the nature of the rite as well, which moved in emphasis from political to mystical. Participation was no longer a matter of becoming a town burgess but of undergoing a literally life-changing experience. When the Ptolemaic (Greek) pharaohs became established in Egypt, their Alexandrian capital expanded to include a new suburb named for Eleusis, with its own cult of Demeter offering initiations patterned on the Greek originals. The influence of Eleusis spread to another popular cult, the ecstatic rites of Dionysus. As god of wine, Dionysus had long encouraged his followers to seek the transpersonal in group dancing, drinking, and sexual release. Now the emphasis slowly shifted toward individual salvation.

The Mysteries, from whatever source offered, were open to everyone able to speak Greek, whether they be male or female, freeman or slave, but the initiate was bound by oath to hold the rites absolutely secret. While tens of thousands learned it, that secret was kept, a telling tribute to the power of the central experience. To this day, our knowledge of what really happened in the Mysteries is extremely fragmentary, but there are hints, clues, and small revelations from both archaeology and ancient documents that permit us to patch together a broad picture.

Focus of the rites was the great telesterion (initiation hall) at Eleusis, on the site of which, archaeological digs have confirmed, were a series of buildings from prehistoric times onward. But before the rites could begin, the initiate had to be carefully prepared. A Homeric Hymn, one of thirty-three anonymous Greek texts celebrating individual gods, throws some light on the preliminary rituals. Initiation, it seems, began with a purification. This was carried out by a priest or priestess of the Mysteries while the candidate was seated on a stool, with his head veiled and one foot resting on a ram’s fleece. No record exists to describe the nature of the purification, but there are hints that it may have involved fire. Exactly how is open to speculation: simple censing seems the most likely approach, although more rigorous tests of faith like fire-walking cannot be completely ruled out.

Purification was followed by a nine-day fast, during which the candidate was allowed neither food nor wine, although it is unclear whether other liquids were permitted. Given a maximum daily temperature of 26.7ºC (80.06°F),2 it is possible to survive for nine days without water, but only at the risk of near-terminal dehydration. Nonetheless, if the aim of a Mysteries initiation was to induce an altered state of consciousness, a risky ordeal of this sort may have been considered acceptable. During or immediately after the fast period, the initiate was obliged to take part in a vigorous all-night festival (pannychis), which involved torchlit dances around the well Callichoron, still visible at the entrance to the Eleusinian sanctuary to this day.3 Here too one can see the possibility of an altered state.

The fast was broken with a special drink combining barley, water, and pennyroyal. Although pennyroyal oil is highly toxic, indeed lethal, in quite small doses the herb itself was used in a culinary capacity in ancient Greece and to flavor wine. Taken as an infusion, one of its medicinal properties is to promote sweating. Some authorities have speculated that the barley used in the preparation might have been (purposely) contaminated by ergot, a fungus known to induce hallucinations. Thus, if we take the preliminaries as a whole, their similarity to shamanic preparations involving exhausting ordeals and psychotropic plants becomes evident. What evidence we have clearly points to initiation as the induction of a mind-altering experience.

When Athens took over the Eleusinian Mysteries, the preliminaries became more complex and a new structure was introduced formalizing what was known as initiation into the Lesser Mysteries. These rites took place in Athens, while the ultimate initiation of the Greater Mysteries remained centered on Eleusis. Purification was still an important preliminary and now included a sort of baptism in the River Ilissus. Here too there is a possibility that the aim was an altered consciousness. In a later era, the famous Qabalistic rabbi Isaac Luria developed a system of total immersion designed to trigger higher visionary states. Adepts in this system first entered a river, lake, or special ritual bath called a mikvah. Before immersing themselves completely, they were required to engage in a complex meditation on the term mikvah, then on the word nachal, a stream. When this was completed, they were instructed to immerse themselves fully in the water, then emerge with the words Im tashiv miShabbat raglecha, a quotation from the book of Isaiah that translates, “If you rest your foot for the Sabbath.” Although the meditative sequence, which involved the divine names of God, was an intellectual powerhouse, it seems from texts left by Luria’s pupils that the act of immersion was the main thing. Breath retention, which forms such an important part of Oriental yoga systems, combined with visualization and other forms of meditation is another tested route to mystical experience. One school of thought even holds that early Christian baptism was not the symbolic sprinkling used in churches today, nor even the (brief) total immersion of some fundamentalist denominations. Instead it is argued that the earliest Christians were held under water at the literal risk of their lives until oxygen starvation forced a change of consciousness with visionary experiences analogous to the life of a drowning man flashing before his eyes. But whatever might have been experienced, initiation into the Lesser Mysteries at Athens was seen as no more than a preparation for entering the Greater Mysteries later in the year. Consequently, the ceremonies had an instructive content, although scholars have yet to discover exactly what knowledge was imparted.

The Greater Mysteries were held in the month of Boedromion (September –October) from the fifteenth to the twenty-third day. Two grades of admission were on offer, with a full year between them and admission to the second grade dependent on initiation into the first. This final grade was known as the epopteia, perhaps tellingly, since the word translates as “vision.” The opening day of the ceremony began with a solemn gathering in Athens and the arrival of certain sacred objects, carried in special boxes, from Eleusis. A priest commenced proceedings with a proclamation naming the classes of people who were forbidden participation in the Mysteries—basically those who could not speak Greek and criminals. The following day there was a grand procession to the coast, with the candidate for initiation accompanied by a live pig, an animal sacred to Demeter.4 Both pig and candidate were required to take a ritual bath in the sea.

Another procession took place on the nineteenth or twentieth of the month, this time a fourteen-mile journey to Eleusis itself. We know it was called the Iacchus Procession after Demeter’s son who personified the ritual cry of joy uttered during the march. On the way there was dancing, various ceremonies, the singing of hymns, and sacrifices. Curiously, it was also traditional for participants to lighten the more sober aspects of the celebration by telling obscene jokes about prominent citizens. The arrival at Eleusis was marked by further dancing before the candidate retired to rest in anticipation of his initiation the following day.

What happened during an initiation is less certain than the foregoing descriptions of the preliminaries. Archaeological investigation shows that the ceremony took place in a huge square hall of fifty-one-meter sides with wide, stepped tiers of seats capable of accommodating an astonishing four thousand spectators. There is speculation that a small room once stood in the center of this vast space, functioning as a sanctuary for the hierophant who conducted the ceremony.5 Evidence of the ceremony itself is largely drawn from a Latin work of fiction, the Metamorphoses of Apuleius, and the suspect writings of disapproving Christians. Nevertheless, there are just enough correspondences between the various accounts to allow us a reasonable degree of certainty about the broad outlines of what went on.

The ritual was divided into three parts—legomena, or “things spoken,” dromena or “things performed,” and deiknymena or “things revealed.” The first of these was almost certainly brief. We have it on the authority of Aristotle that candidates for initiation did not go to learn but to be put in a particular frame of mind. The emphasis was always on emotion and experience, points reiterated by other writers in the ancient world.

“Things performed” may have included the enactment of a sacred marriage between Hades and Persephone, or possibly Zeus and Demeter. Bishop Asterius of Amasea (ca. 350–410 CE) suggests this involved a sex act between the hierophant and a priestess, a possibility that may have been more spiritual than it must have appeared to the bishop. There is a technique of Oriental tantra in which a couple identify with a specific god and goddess during the sex act in order to communicate with the divinities and/or channel their energies. The tantric “magic” works by changing the consciousness of the participants in such a way that permits an experience of direct spirit communication. It is possible that some similar technique could have been developed within the Greek Mysteries.

Another known aspect of “things performed” was a light show that accompanied the revelation of certain sacred objects to the candidate. An inscription at Eleusis tells of the hierophant “coming from the shrine and appearing in the luminous nights.” Another describes the scene as “clearer than the light of the sun.”6 The light show seems to have immediately preceded the final act of the Mystery—the revelation. Hippolytus of Rome, a third-century CE theologian, claimed this was nothing more than a single ear of corn, dramatically produced by the hierophant amid many fires. Although widely quoted and supported by academics to the present day, this seems unlikely. Initiates of the Greater Mysteries were described as joyous, having been granted a far more positive view of both life and death than was offered by orthodox Greek religion. In short, they underwent a profound and lasting change. This seems a tall order for a single ear of corn, even if the plant was closely associated with the goddess Demeter. If we consider the various elements that made up the Greek Mysteries—the fasting, the ordeals, the breath control, and the possibility of a mind-altering drink—the parallels with shamanic practice become obvious. In view of this, the likelihood is that the final initiatory experience, guided and to some extent controlled by the ceremonial, was a visionary meeting with the goddess herself—in other words, a spirit contact. If so, it would not be the only spirit contact to influence the culture of ancient Greece.

Today, Epidaurus in southern Greece is a vast, multilevel archaeological site surrounded by rocky heights thinly covered in Mediterranean shrub. In classical times, it was a small but thriving city and contained arguably the most popular tourist attraction of the known world. The great Doric temple of Asclepios measured eighty meters in length and, according to an inscription discovered at the site, took almost five years to complete. But it was not its architectural splendor that attracted visitors, nor even the exquisite gold and ivory statue of the god. The thousands who flocked there, not merely from Greece but from surrounding countries and beyond, came mainly in the hope of a cure for their ills. For the Asclepion was a place of healing, with a reputation for producing miracles.

But while there was a hall where patients might sleep—the Abaton—any further resemblance to a modern hospital was almost entirely coincidental. The shrines of Asclepios—at Epidaurus, Cos, Pergamum, and many other sites throughout Greece—were impressive examples of architecture and landscaping. Cypress groves enclosed springs, baths, long colonnades, and peristyles, as well as huge open-air altars and soaring temples to a variety of gods. Epidaurus had its own tiered ampitheater, Pergamum a library. A visitor to the shrine typically passed through an imposing entrance along a well-trodden path past a small temple of Artemis to the altar of Asclepios himself. There he might make sacrifice—an ox if he was rich, a cockrel sacred to the god, or a body part in precious metal signifying the area of illness. From there he might proceed to the Tholos, or purifying bath of waters drawn from a sacred spring. Depending on his condition, medical priests could insist on several days of a cleansing diet before the real healing began.

Once cleansed, he was permitted to enter the Abaton. This was essentially a dormitory administered by white-robed priests. It was also the home of a great many nonvenomous snakes, creatures sacred to Asclepios. Within this extraordinary environment, the patient was put to bed and encouraged to sleep. In his dreams, the god would come and either effect a cure directly so that he awoke restored, or prescribe a course of treatment for him to follow. When morning came, the priests of the temple would help him remember his dream and interpret its meaning in those cases where it was not already clear. Sometimes the god might not enter the dream in person but send one of his totem animals—a dog, rooster or snake—in his place.

Although dream incubation of this type is today open to a purely psychological explanation—the patient’s expectations are aroused by the temple visit so that his unconscious ensures he dreams of the god—to the ancients themselves it was, without question, an example of spirit communication. Whether psychological or paranormal, it worked. Six marble tablets, all that remained of a great many more, were discovered along the inner wall of the northern colonnade that bordered the sacred enclosure. They contained a remarkable record of iamata or cures, some bordering on the miraculous, carried out in the sanctuary.

Although Strabo records that the earliest temple of Asclepios was at Trikka, the birthplace of the god, the healing temple at Epidaurus claimed primacy and its methods proved so effective that similar Asclepions were established at Cos, Pergamum, and eventually throughout the whole of the country, usually in settings of awe-inspiring natural grandeur. Soon they too were recording their own iamata. In the Lebena Asclepion on Crete, archives describe how the god performed a surgical operation on Demandros of Gortyn while he was asleep. Even more oddly, a sleeping woman was cured of her infertility through the use of a cupping instrument known as a sikya.7 She became pregnant soon after leaving the sanctuary. The exact nature of these two Cretan cures is not entirely clear from surviving descriptions. It is possible that the surgical operation literally took place and involved some form of anesthesia, which may have involved the administration of an herbal drug or the use of hypnosis—priests at the temple were known to be able to induce “sleep” in certain patients, an indication that an early form of hypnotism formed part of the treatment regime. The fact that the surgery was attributed to the god could easily be a religious convention, with the actual operation carried out on his behalf by a priest. The case of the infertile woman is also suggestive of actual physical treatment. Cupping, now mainly used by acupuncturists, involves placing a small quantity of flammable material on a (protected) area of the body, setting it alight, then immediately covering it with a cup or similar vessel. As the fire consumes the oxygen inside the cup, a partial vacuum is created that sucks on the area underneath the cup to therapeutic effect. A sikya, in Ancient Greece, was a vessel used for this type of treatment.

But despite these indications of physical intervention, the iamata leave no doubt at all that the main healing technique in the various Asclepions was the incubation of dreams for spirit contact. Some of these produced bizarre results if the records are to be believed. Pandarus of Thessaly, for example, suffered from an embarrassing mark on his forehead. After he entered the Abaton at Epidaurus, Asclepios appeared to him in a dream and placed a bandage around his head, warning him not to remove it until the god had gone. Pandarus did as instructed and later took off the bandage, to find the mark had been transferred from his forehead to the cloth. When he awoke, the physical mark had disappeared as well.8 As an act of gratitude, Pandarus sent his friend Echedorus—who had a similar mark on his forehead—to Epidaurus with a gift of money to pay for the erection of a statue of Athene in the shrine. But Echedorus was untrustworthy and kept the cash for himself. When he went to sleep, however, Asclepios appeared to him in a dream and asked about the money. Echedorus flatly denied having received it but promised to paint a picture and dedicate it in place of the proposed statue. The god was not satisfied with the offer and wrapped the bandage used by Pandarus around the head of Echedorus. When Echedorus awoke, the forehead marks of Pandarus had been added to his own.

Other recorded dream cures included that of Euhippus who suffered from a broken spear point embedded in his jaw. During an induced dream in the Abaton, the god drew out the point and carried it away, leaving the patient free from pain (and presumably from the spear point) when he awoke. Clinatas of Thebes was rid of a lice infestation when Asclepios appeared in his dream to brush him down with a stiff broom.

The iamata can be unclear at times about what happened in a dream and what in the waking state. To the Greek mind, the two were almost interchangeable: actions carried out on the dream body were automatically transferred to the physical. Sometimes there was an observable crossover. One patient who presented himself at the Asclepion had an ulcerated toe. He dreamed that a handsome youth treated his affliction with a special remedy and woke cured. But priests on duty at the temple claimed the cure had actually taken place when one of the sacred snakes licked the toe.

Dreams were not thought to be subjective experiences, as they are today. The Greeks appear to have believed the dream state was something akin to another world that people could visit in sleep. Consequently, it was perfectly possible to dream on behalf of someone else. When Arata of Laconia fell foul of dropsy and was too ill to travel, her mother journeyed to Epidaurus to incubate a dream for her. In the Abaton the mother dreamed that the god removed her daughter’s head and drained it of liquid before restoring it to her shoulders. Curiously, Arata had the same dream and was free of her affliction by the time her mother returned home.

Sometimes a worthy patient did not find his way to an Asclepion of his own accord—he might be summoned by the god in a dream or, more rarely, a waking vision. The second-century CE writer Aelius Aristides recorded a personal experience of this phenomenon is his diary, which he later published as Hieroi Logoi or “Sacred Tales.” Aristides lived in Smyrna, an ancient Greek city located on the Aegean coast of Anatolia and ruined his health on a rigorous midwinter journey across the Balkans to the Adriatic and Rome. By the time he came home again, he was suffering from convulsions, breathing difficulties, and periodic paralysis. In this sorry state, he had a dream during which he was summoned to become a devotee of Asclepios at his Pergamum shrine. For seventeen years, Aristides placed himself entirely in the hands of the god—and cold hands they turned out to be. Asclepios prescribed exhausting fasts, emetics, purges, bloodletting, naked winter runs around the temple, plunges into frozen rivers and lakes, special foods, and long periods when he was forbidden to wash. Not altogether surprisingly, Aristides eventually tired of this treatment and turned to human physicians for help, but Asclepios promptly punished him for his faithlessness by inflicting him with chills, digestive ailments, and catarrh. On the positive side, however, Aristides believed the god protected him in times of plague, brought him favor with the authorities, and arranged for the defeat of his literary rivals.

Although by far the most popular, Asclepios was not the only god of healing in Greece—Apollo was probably second favorite, but there were many others. As their following increased, the technique of dream incubation for spirit contact spread beyond the boundaries of the country. In the third century BCE, Ptolemy I established Greek rule in Egypt and shortly thereafter was visited in a dream by a god who introduced himself as Serapis and demanded that his statue be brought from the Black Sea coast and established in Alexandria, the new Egyptian capital. Although Serapis promised benefits to the kingdom, Ptolemy procrastinated so that the god had to come again, with threats this time, in a second dream. This time Ptolemy caved in at once and not only fetched the statue but had a new Serapeum built in Alexandria to house it. True to his word, Serapis thereafter began to appear in the dreams of the sick, with therapeutic effect. But he was a more demanding deity than Asclepios and induced in his devotees at Memphis and elsewhere a state called katoche during which they were compelled to obey his commands until released into normal consciousness.

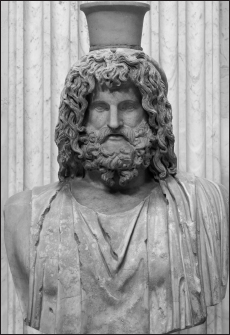

Serapis, the healing god established in Alexandria following spirit instructions given in a pharaoh’s dream

An artist’s impression of a Delphic priestess, whose trance communications with spirits guided the ancient world

Serapis shared his Memphis shrine with a native Egyptian deity named Imhotep—a real person who was deified after his death as Imouthes. Imouthes was as demanding in his own way as Serapis and just as unpredictable. When a scribe failed to publish a book on Imouthes’s healing miracles, this god struck him down with a fever as punishment, then appeared in a dream to cure him with a single look.

That dream incubation spread to Egypt was predictable enough, since Egypt was now ruled by a Greek pharaoh, but the reason for its spread to Rome was bizarre in the extreme, if contemporary accounts are to be believed. According to these sources, Rome was suffering the ravages of plague in 292 BCE and sent a deputation to the Greek oracle at Delphi in the hope of advice. The oracle told them to visit Epidaurus. When the mission arrived, its members were greeted by a huge serpent that appeared from under a statue of Asclepios and then boarded the Roman ship and went to sleep beneath a tent. Firm believers in omens, the Romans left it where it was and sailed for home. The snake swam ashore at Antium, where it remained for three days coiled around a tree before boarding the ship again. When the ship entered the Tiber, it went ashore on Tiber Island and disappeared … as, almost at once, did the raging plague. The grateful Romans built their first Asclepion on the island and established worship of the healing god under his Latin name, Aesculapius.

The Delphic Oracle that advised this deputation was another, considerably more famous, example of spirit communication in the world of ancient Greece. According to the Greek historian Diodorus, the Delphic Oracle came into being because of the activities of a goat. A goatherd watched the animal peer into a crack in the ground known as the “Delphic chasm,” then begin to leap about in an extraordinary manner. Other goats approaching the chasm exhibited the same peculiar behavior. So did the goatherd when he went to investigate, but with one important difference: he immediately began to utter prophecies. Word of the phenomenon quickly spread and vast numbers of people made pilgrimage to see for themselves. Unfortunately many were overcome by the fumes and sent tumbling into the chasm so that the authorities proclaimed it a health hazard and decreed that henceforth only a single, specially appointed woman would be permitted to prophecy. She was supplied with a tripod to sit on so she would not fall in.

Although a great many authors, ancient and modern, have passed on the theory that Delphic pythia (oracular priestesses) were intoxicated by volcanic fumes,9 there is no archaeological evidence of any fissure under the Delphic temple. Proponents of the Diodorus theory suggest it may well have closed over during an earthquake, but the Roman author Lucan proposed a different explanation altogether. He held that the priestess was able to prophesy because she was temporarily possessed by the god Apollo.

Lucan never visited Delphi in person, so his description of a pythia rushing around in the grip of divine madness is suspect, but other accounts do little to dispel the idea that some form of mediumship was involved. Certainly Delphi was presented to a believing public as the voice of Apollo, who selected the spot by killing the “blood-reeking bane”10 of a female dragon that had been terrorizing the countryside. The idea that gods or other spirits spoke through oracles had wide popular currency. In his play Elektra, Euripides writes how Orestes attributes the words of an oracle to an alastor or mischievous spirit when it advises him to kill his mother. No member of his audiences would have found the suggestion unlikely.

It is worth remembering that the ancient Greeks had no holy scriptures they could turn to for guidance, nor did their priesthood offer living advice in anything analogous to the modern Sunday sermon. But people then and now had the same deep-rooted human need for direction so that Delphi, despite its fame, was far from the only oracular temple in the Greek world. There were others spread across the entire country with Dodona, Claros, and Didyma among the more popular sites. Most of these subsidiary oracles, like Delphi itself, were dedicated to Apollo and virtually all made their pronouncements through an entranced medium, male or female, speaking with changed voice and personality as the temporary incarnation of the god. Often their answers were garbled, leading to the widespread belief that the gods had little time for rash inquiries (which seemed to be most inquiries pertaining to mundane human affairs) and were not above confusing or even misleading their authors. As a consequence, a structure of questioning developed within which the querient was not permitted to hear the medium’s actual reply but only its interpretation, delivered in verse by a priest. There was also expense involved. At Delphi, a single question could cost the equivalent of two days’ wages, plus additional “freewill” offerings. But this was the minimum cost only for private inquiries. Governments and individuals in positions of power could expect to pay ten times as much. Many were happy to do so and their questions, related to potential wars and similar matters of life and death, ensured that the political fate of whole provinces and even countries rested on spirit utterances.

But it would be quite wrong to assume the spirits of Greece influenced only her contemporary cultures. Greece is widely acknowledged as the cradle of Western civilization, which allows us to deduce that many of the philosophies we embrace so instinctively today were bequeathed to us by ancient spirit voices. Moreover, even the most superficial study of history shows a similar bequest was made to us by that other great classical civilization, the military culture of ancient Rome.

According to Livy, the very foundation of Rome was marked—and marred—by spirit contact. Having decided to found a new settlement, the twins Romulus and Remus began to quarrel about which of them the town should be named for and who should govern it. Since they could reach no agreement, they decided to ask the tutelary gods of the countryside to make the decision for them by augury. The brothers then retired to separate hills—Palatine and Aventine—to await their respective signs. Remus was the first to hear from the spirits when six vultures appeared, but shortly afterward twelve of the same birds appeared to Romulus. Livy writes, “The followers of each promptly saluted their master as king, one side basing its claim on priority, the other upon number. Angry words ensued, followed all too soon by blows, and in the course of the affray, Remus was killed … This, then, was how Romulus obtained the sole power. The newly built city was called by its founder’s name.”11

It is difficult to know how much truth lies in this intriguing tale. There is no archaeological evidence of the original settlement and historian Robert Hughes describes Rome’s accepted foundation date, 753 BCE, as “wholly mythical.”12 What is certain is that augury of the type Livy described did not end with Romulus and Remus but came to dominate the thinking of patricians, politicians, and plebeians alike across the centuries as the settlement became a city and the city became an empire. Tradition has it that King Romulus established a College of Augurs sometime between 735 and 716 BCE. At this period it had no more than three members, but by 81 BCE the number had increased to fifteen. For several centuries, serving augurs elected new members to the college, but this right disappeared in 103 BCE and the appointment of augurs was politicized.

Augury itself was not, as many assume, a procedure designed to foretell the future, nor even to determine a correct course of action. Rather it sought to discover whether a particular decision, already made, found favor with the gods and thus should be acted upon or abandoned. In other words, it was a system of communication with spirit beings created to ensure their approval of human actions. As such, it is worth noting, a favorable augury could only really be judged in retrospect. If the signs appeared favorable, but the outcome proved catastrophic, then the augur must have misread them in the first place.

College augurs handed down the techniques of their craft to new members of the profession—a profession that carried with it enormous prestige and power. Augurs were consulted prior to every major undertaking in Roman society, both public and private. Their findings determined matters of trade, diplomacy, war, and even religion. To make those findings, an augur would first don the trabea, a state robe edged with purple, reserved for members of his profession, kings, and certain priests and knights. He would then retire to high ground, or sometimes a tower, cover his head with a special cowl, and place his left foot on a boulder.13 From this elevated position, he turned his face eastward and used a short, straight rod with a right-angled bend at one end to mark out the heavens into four quarters. Then he waited for a sign from the gods, related to the undertaking in question. When such a sign appeared, it was not considered a valid augury until confirmed by a second sign of the same type. There were several groups of omens to which particular attention had to be paid. The first, and arguably most important, were signs in the heavens themselves—a flash of lightning, a roll of thunder, the appearance of a meteorite or comet, or the behavior of birds, notably vultures, eagles, owls, and crows. The augur might take note of whether thunder came from his right or left, whether lightning produced an odd or even number of strokes, the appearance and direction of a flight of birds, or possibly even the sounds they made. When the augur dropped his eyes from the heavens, he might typically watch out for the appearance of a wild animal like a fox or a wolf, interpreting the direction from which it came and whether it crossed the horizon or ran parallel to it.

A more artificial, but extremely popular, method of divining the will of the gods involved the use of sacred chickens.14 Birds reserved for this purpose were kept in a coop and generally consulted by the augur early in the morning. In a short but solemn ceremony, he would order a moment of silence, then throw down a handful of corn and open the coop. If the chickens swooped directly on the food and ate heartily, it indicated that the gods were pleased about the undertaking in question. But if the chickens refused to eat, flew away, or scattered the food with their wings, the augur would pronounce the omen unfortunate and predict trouble ahead if the proposed course of action was carried through. There was, apparently, no way of avoiding the will of the gods. Prior to the naval Battle of Drepana in 249 BCE, the consul Pulcher ordered a chicken-based augury for his planned attack on the harbor. When released, the chickens refused to eat, but instead of abandoning his plans, Pulcher snapped, “Bibant, quoniam esse nolunt” (“Let them drink if they won’t eat”) and threw the birds overboard. The move reassured his crew sufficiently to follow him into battle, but the attack failed miserably, the battle was lost, and almost all of Pulcher’s ships were sunk.

Running parallel to the work of the augurs were the activities of the haruspices, with whom augars are sometimes confused in popular modern accounts. A haruspex was a priest trained in the art of divining the will of the gods by examining the behavior and entrails of sacrificed animals. Typically, the animals offered in sacrifice would be sheep or poultry. The haruspex would carefully observe the animals’ behavior and condition before they were killed, and the condition of their entrails—notably the liver—after death. If the caput iecoris (head of the liver) was missing, this was seen as a particularly bad omen. In Euripides’s play Elektra, an incomplete liver signaled the impending death of one of the characters.

To the modern mind, there seems little to choose between the oracular practices of augury and haruspicy. Both seem superstitious, even silly, and curiously lacking in any real spirit contact. But one ancient tale may provide a hint as to why we should not rush to judgment—at least on the question of augury. Livy’s History of Rome, written in the first century BCE, describes how the third king of Rome, Tullus Hostilius, received word of a shower of stones that had fallen on the Alban Mount, the second-highest peak of the Alban Hills near Rome. The mount was a long-extinct volcano and this indication of renewed activity quickly persuaded Hostilius to send an investigatory expedition.

When the men arrived at the mount, they discovered it was indeed mildly active—they were greeted by their very own hailstorm of pebbles—but not so much that it prevented a climb. When they did so, they received a great augury at the lucus cacumen, the hill’s topmost grove. A spirit voice emerged from the trees to dictate instructions concerning religious observances. Hostilius was sufficiently impressed to order a nine-day festival to mark the event, a celebration repeated when there were subsequent reports of stony rains.

The incident on the Alban Mount was not the only example of verbal augury. The accepted list of omens to be considered by every member of the College of Augurs included “unusual incidents,” such as the hearing of strange voices and the appearance of apparitions. In the De Divinatione (“Concerning Divination”), our best source of information on the divinatory practices of Roman times, Cicero is careful to distinguish between the sort of “cookbook” augury that could be learned by rote and the divinely inspired communication with the gods that took place in an ecstatic trance. A similar distinction was made by Plato,15 suggesting that at least some examples of augury, and possibly even haruspicy, involved neo-shamanic techniques of spirit communication.

The same suspicion hangs over another popular Roman institution, the Mithraic Mysteries, which flourished from about the first to the fourth centuries CE and were strongly supported by the Roman military. Like their Elusion counterparts in Greece, little is definitively known about the Mysteries of Mithras. The Roman Mysteries were bound by oaths of absolute secrecy and no text recounting their innermost activities has survived. But a multitude of subterranean temples have, and archaeological investigation has enabled us to piece together a “best-guess” scenario of what went on.

The Romans themselves believed these Mysteries originated in Persia—Mithra is a Persian god and Mithras the Greek adaptation of his name—but modern scholarship fashionably claims that the cult was indigenous to Roman imperialism and may even have arisen as a counterbalance to early Christianity. There is less controversy about its symbolism. Reliefs of the young Mithras slaying a bull have led scholars to believe the worship likely involved bull sacrifice, while a multitude of eating vessels and implements found at Mithraic sites strongly suggests feasting as part of the ritual. We can also be certain that the Mithraic Mysteries were initiatory—and with that certainty come important pointers toward the sort of spirit contact embodied in the Greek Mysteries. There were seven grades in all, ranging from corvex (crow or raven) through nymphus (male bride), miles (soldier), leo (lion) Peres (Persian), heliodromus (sun-runner), to the supreme grade of pater (father). Entry into each grade was conditional on the candidate having survived a particular ordeal, often in a pit dug into the floor of the Mithraeum. The emperor Commodus (r. 180–192 CE) is alleged to have introduced Mithraic trials specifically designed to kill the candidate as a sop to his own sadism, but even the more routine tests, involving exposure to heat, cold, and other perils, were dangerous. If the candidate survived, he immediately came under the protection of the god associated with his new grade—Mercury for corvex, Venus for nymphus, Mars for miles, Jupiter for leo, Luna for Perses, Sol for heliodromus, and Saturn for pater. On achieving the grade of leo, the candidate’s ethical emphasis became that of purity. The resemblance to shamanic rites in which purifications and life-threatening ordeals led to the knowledge and protection of certain spirit entities is too obvious to require further comment.

Another, more subtle link with the institutionalized spirit contacts of ancient Greece—and indeed ancient Egypt—may lie in the curious figure so often discovered in Mithraic temples that today attracts the scholarly designation of leontocephaline. The figure, as the name suggests, depicts a (naked) man with the head of a lion, often openmouthed and threatening. An enormous serpent coils around his body. In the version found in the Mithraeum at Ostia Antica there is an engraved tablet behind the figure, a caduceus and chicken at his feet. Other representations elsewhere include the figure of a god. Serpent, rooster, and dog are all symbolic companions of Asclepios, while the caduceus is associated with Mercury, messenger of the gods and guide of the dead. The Egyptian association with this near-ubiquitous figure lies in the lion head. The Egyptians typically experienced their gods as animal-or bird-headed humans, itself a curious link with ancient shamanism. There is even a lion-headed deity—Sekhmet—in the Egyptian pantheon, although unlike the Mithraic figure, she was conceived of as female.

Although the signs of spirit communication are less obvious in ancient Rome than they are in ancient Greece or Egypt, there are pointers to the possibility that such communication existed. Beyond this, there is absolute certainty that the Roman people firmly believed that spirit beings played a part in their everyday lives and went to considerable lengths to ensure their benevolence. Thus, here again, we have clear evidence of spirit influence on an ancient culture and one, in this instance, that bequeathed us the entire foundation of our Western legal system. Furthermore, if we consider the Roman empire as a whole, we find within its far-flung confines the early indications of a spirit contact that was to influence profoundly the whole of Western esoteric thought.

![]()

In 598 BCE, the Babylonian emperor Nebuchadnezzar launched a massive attack on the little kingdom of Judah. It was a grossly uneven conflict and within a year the remnant Israelite community had all but collapsed. By 597 BCE, the capital Jerusalem surrendered. But despite appearances, the war was far from over. A resistance movement sprang up and hostilities renewed. In an attempt to break the spirit of the Israelites, Nebuchadrezzar instituted a policy of mass deportation, concentrating on the brightest and best of the conquered people. Among those who joined the earliest forced marches to Babylonia was a temple priest named Ezekiel.

Ezekiel was well thought of by his fellow exiles and quickly became spiritual adviser to their leaders. He seems to have been a flamboyant character, given to grand gestures. On one occasion he ate a scroll in order to make a point. On another, he lay on the ground pretending to fight with unseen opponents. He was likely to fall on his face or be struck dumb for long periods of time. But despite these peculiarities, people took him very seriously—and with good reason. While Jerusalem was under siege, his wife became terminally ill and the force of his grief convinced him to make a grim prophecy: the city would be destroyed “and your sons and daughters whom you left behind shall fall by the sword.” All too soon his prediction came true.

The Babylonian exile left Ezekiel at Tel-abib by the river Chebar, a canal that formed part of the Euphrates irrigation system in what is now southern Iraq. On July 31, 592 BCE, he was walking on the banks of the Chebar when something quite bizarre occurred. Ezekiel later described it in his own words:

And I looked, and, behold, a whirlwind came out of the north, a great cloud, and a fire infolding itself, and a brightness was about it, and out of the midst thereof as the color of amber, out of the midst of the fire. Also out of the midst thereof came the likeness of four living creatures. And this was their appearance they had the likeness of a man. And every one had four faces, and every one had four wings. And their feet were straight feet and the sole of their feet was like the sole of a calf’s foot: and they sparkled like the color of burnished brass. And they had the hands of a man under their wings on their four sides and they four had their faces and their wings. Their wings were joined one to another they turned not when they went they went every one straight forward.

As for the likeness of their faces, they four had the face of a man, and the face of a lion, on the right side: and they four had the face of an ox on the left side they four also had the face of an eagle. Thus were their faces: and their wings were stretched upward two wings of every one were joined one to another, and two covered their bodies. And they went every one straight forward: whither the spirit was to go, they went and they turned not when they went.

As for the likeness of the living creatures their appearance was like burning coals of fire, and like the appearance of lamps: it went up and down among the living creatures and the fire was bright, and out of the fire went forth lightning. And the living creatures ran and returned as the appearance of a flash of lightning.

Now as I beheld the living creatures, behold one wheel upon the earth by the living creatures, with his four faces. The appearance of the wheels and their work was like unto the color of a beryl: and they four had one likeness: and their appearance and their work was as it were a wheel in the middle of a wheel. When they went, they went upon their four sides: and they turned not when they went. As for their rings, they were so high that they were dreadful and their rings were full of eyes round about them four.

And when the living creatures went, the wheels went by them: and when the living creatures were lifted up from the earth, the wheels were lifted up. Whithersoever the spirit was to go, they went, thither was their spirit to go and the wheels were lifted up over against them: for the spirit of the living creature was in the wheels. When those went, these went and when those stood, these stood and when those were lifted up from the earth, the wheels were lifted up over against them: for the spirit of the living creature was in the wheels.

And the likeness of the firmament upon the heads of the living creature was as the color of the terrible crystal, stretched forth over their heads above. And under the firmament were their wings straight, the one toward the other: every one had two, which covered on this side, and every one had two, which covered on that side, their bodies. And when they went, I heard the noise of their wings, like the noise of great waters, as the voice of the Almighty, the voice of speech, as the noise of an host: when they stood, they let down their wings. And there was a voice from the firmament that was over their heads, when they stood, and had let down their wings.

And above the firmament that was over their heads was the likeness of a throne, as the appearance of a sapphire stone: and upon the likeness of the throne was the likeness as the appearance of a man above upon it. And I saw as the color of amber, as the appearance of fire round about within it, from the appearance of his loins even upward, and from the appearance of his loins even downward, I saw as it were the appearance of fire, and it had brightness round about. As the appearance of the bow that is in the cloud in the day of rain, so was the appearance of the brightness round about. This was the appearance of the likeness of the glory of the Lord.16

This “vision of Ezekiel,” as it came to be called, was so peculiar that several twentieth-century authors—including a former NASA engineer—decided the priest must have witnessed a spaceship landing. Generations of rabbis have disagreed. To them, Ezekiel was granted a vision of God.

The term merkava, sometimes spelled merkabah, is Hebrew for “chariot” or “throne” and has the latter translation in the passage above.17 The throne described by Ezekiel came increasingly to function as the focus of contemplation for early Jewish mystics. By 40 BCE, the year Judea became a Roman province, Jewish holy men had begun to experiment with a visionary system that would allow them to share the experience of Ezekiel. By the first century CE, Merkava mysticism was flourishing in Palestine. Six centuries later, it had not only spread to Babylonia, but centered itself there, in the home of Ezekiel’s original vision.

The mystical experience is common to all the world’s religions and is characterized by a realization of ultimate unity. But the interpretation of the experience tends to be colored by the cultural background and belief system of the individual. Thus, while a Buddhist or Hindu might speak of transcendent unity with the cosmos, a Jewish—and, indeed, Christian—mystic will often describe what has occurred as union with God. The experience itself will sometimes arise quite spontaneously, but more often it results from the application of certain techniques. While the most important of these—prayer and fasting—have religious connotations, others are more occult, with a distinct crossover between mysticism and magic.

The tzenu’im, Merkava initiates, were drawn from a select few judged to be of the highest moral caliber. They had to prepare themselves for their experience by fasting, then embarked on what was believed to be an extraordinarily dangerous visionary journey through seven “heavenly dwellings,” each one guarded by a hostile angel. It was in these heavenly dwellings that the magical element of Merkava training came into play. The initiate used specific magical formulas—referred to in Merkava literature as “seals”—in order to control, or at least placate, the guardians. It was believed that use of the wrong seal could prove fatal, or at best result in serious injury.

Once the journey through the celestial spheres was completed, these explorers of the supernatural world (Yorde Merkava) were convinced they would be granted sight of the divine throne—the same vision encountered by Ezekiel on the banks of the Chebar.

Although initially viewed with distrust by mainstream Judaism—the Talmud suggests that half of those who take the celestial journey will die or go mad—Merkava doctrines evolved over centuries to become the mystical heart of the Jewish religion. In developed form, they constitute that body of teaching now known as the Holy Qabalah. It is a body of teaching that has profoundly influenced the practice of magic and the techniques of spirit contact in the Western world right down to the present day. But it is important to note that the influence of spirit contact has not been confined to the Western world.