![]()

THE DARKNESS THAT ENVELOPED EUROPE DURING THE EARLY MIDDLE Ages was not a worldwide phenomenon. The lights of learning that went out across Europe, as the Romans retreated, remained lit throughout the Middle East where Arab respect for and development of the sciences was a beacon to the world. Yet, as in every earlier civilization, contact with the spirit world remained. Prior to the advent of Islam, Arabs “lived and died with magic—they spoke to the good genii, the Djinns.”1 Against this cultural background, in 570 CE, there occurred the birth of a child who was destined literally to change the world. His name was Ab![]() al-Q

al-Q![]() sim Mu

sim Mu![]() ammad ibn

ammad ibn ![]() Abd All

Abd All![]() h ibn

h ibn ![]() Abd al-Mu

Abd al-Mu![]() alib ibn H

alib ibn H![]() shim. Today he is known more simply as Muhammad.

shim. Today he is known more simply as Muhammad.

The boy’s parents, ![]() Abd All

Abd All![]() h and

h and ![]() minah, belonged to the ruling tribe of Mecca responsible for guarding the city’s most sacred shrine, the Ka‘bah, while his grandfather,

minah, belonged to the ruling tribe of Mecca responsible for guarding the city’s most sacred shrine, the Ka‘bah, while his grandfather, ![]() Abd al-Mu

Abd al-Mu![]() alib, was a community leader. Nonetheless, his earliest years proved hard. His father died before the boy’s birth. In accordance with the custom held by all the great Arab families at the time, his mother,

alib, was a community leader. Nonetheless, his earliest years proved hard. His father died before the boy’s birth. In accordance with the custom held by all the great Arab families at the time, his mother, ![]() minah, sent him as a baby to live among the Bedouin tribesmen of the deep desert. The belief held was that life in the desert taught a boy nobility and self-discipline, while giving him a taste for freedom. It took him away from the potential corruption of the city and offered escape from the cruel dominance of time. In some ways most important of all, it exposed him to the eloquent Arabic spoken by the Bedouin and instilled in him special skills as a speaker. The desert was seen as a place of sobriety and purity. To send a child there was to renew a bond that had existed for generations.

minah, sent him as a baby to live among the Bedouin tribesmen of the deep desert. The belief held was that life in the desert taught a boy nobility and self-discipline, while giving him a taste for freedom. It took him away from the potential corruption of the city and offered escape from the cruel dominance of time. In some ways most important of all, it exposed him to the eloquent Arabic spoken by the Bedouin and instilled in him special skills as a speaker. The desert was seen as a place of sobriety and purity. To send a child there was to renew a bond that had existed for generations.

During his sojourn in this empty wilderness, Muhammad had his first spiritual experience:

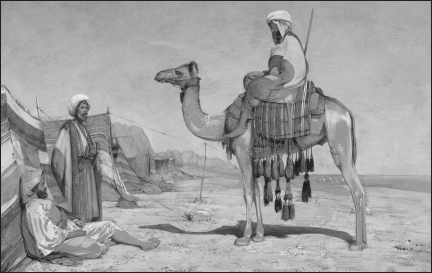

A desert encampment similar to that in which the Prophet Muhammad had his first spiritual experience during his sojourn with the Bedouin as a child

There came onto me two men, clothed in white, with a gold basin full of snow. Then they laid upon me and, splitting open my breast, they brought forth my heart. This likewise they split open and took from it a black clot which they cast away. Then they washed my heart and my breast with the snow.2

When Muhammad was six years old, his mother died, and he was placed in the care of his grandfather. But the old man himself died just two years later and the boy’s upbringing was entrusted to an uncle, Ab![]()

![]()

![]() lib. Apparently he did a good job, for Muhammad grew into a young man whose character eventually earned him the nickname al-Am

lib. Apparently he did a good job, for Muhammad grew into a young man whose character eventually earned him the nickname al-Am![]() n, or “Trusted One.” Citizens of Mecca took to seeking him out as an arbiter in their disputes. Muhammad’s appearance was, according to early sources, quite striking:

n, or “Trusted One.” Citizens of Mecca took to seeking him out as an arbiter in their disputes. Muhammad’s appearance was, according to early sources, quite striking:

[He] was neither tall nor lanky nor short and stocky, but of medium height. His hair was neither crispy curled nor straight but moderately wavy. He was not overweight and his face was not plump. He had a round face. His complexion was white tinged with redness. He had big black eyes with long lashes. His brows were heavy and his shoulders broad. He had soft skin, with fine hair covering the line from mid chest to navel. The palms of his hands and the soles of his feet were firmly padded. He walked with a firm gait, as if striding downhill. On his back between his shoulders lay … a mole.3

The mole, first noticed by his guardian ![]() al

al![]() mah immediately after the vision of the two men in white, was important. Its placement identified it as the Seal of Prophethood, a visible sign of the young man’s destiny.

mah immediately after the vision of the two men in white, was important. Its placement identified it as the Seal of Prophethood, a visible sign of the young man’s destiny.

Muhammad was first married at the age of twenty-five. He accepted the proposal of his employer at the time, a wealthy Meccan woman named bint al-Khuwaylid, who bore him two sons and four daughters. Both boys died young. Ten years later, Muhammad was one of the most respected figures in his native city. He was still being asked to arbitrate on disputes, but by now these were as often civil as personal and sometimes extremely important. On one occasion, for example, the main tribes of the region were at odds over the question of which of them should place the holy black stone in position in the newly restored Ka‘bah. Muhammad was called in to resolve the situation, which he did by placing the stone on his cloak, which was spread on the ground, then having representatives of each tribe lift a corner of the cloak until the stone reached a height where it could be set into the wall.

By now, Muhammad was spending much of his time in prayer and meditation, often in the solitude of the desert. The practice brought him religious visions, some of which he described as like “the breaking of the light of dawn.”4 In the year 610 CE, when Muhammad was forty years old, one of his desert trips brought an experience that was to change his life. Meditating in the cave of al-![]() ir

ir![]() in the Mountain of Light (Jabal al-N

in the Mountain of Light (Jabal al-N![]() r) near Mecca, a spirit with the appearance of a man embraced him and demanded that he “recite.” When Muhammad demurred, the entity embraced him again three times and began to dictate a lengthy message. Muhammad panicked—he thought he might be at risk of possession by djinn or demons—and fled from the cave. The voice pursued. Arab tradition holds that at this point it told Muhammad he was the messenger of God, while the voice itself belonged to the archangel Gabriel. Muhammad believed none of it and ran down the mountain. But then he looked back and discovered that the sky had turned green and was filled in whatever direction he looked by the immense form of an angel.

r) near Mecca, a spirit with the appearance of a man embraced him and demanded that he “recite.” When Muhammad demurred, the entity embraced him again three times and began to dictate a lengthy message. Muhammad panicked—he thought he might be at risk of possession by djinn or demons—and fled from the cave. The voice pursued. Arab tradition holds that at this point it told Muhammad he was the messenger of God, while the voice itself belonged to the archangel Gabriel. Muhammad believed none of it and ran down the mountain. But then he looked back and discovered that the sky had turned green and was filled in whatever direction he looked by the immense form of an angel.

When Muhammad reached home, he told his wife of the experience. She accepted his story without hesitation and sent for her cousin Waraqah, a particularly devout Christian who nonetheless confirmed that Muhammad had indeed been chosen as God’s prophet. Muhammad himself had a second revelation shortly thereafter. It was the beginning of a process that was to last twenty-three years and resulted in the Qur’![]() n (Koran), the sacred scripture of Islam that contains, in Muslim belief, the word of God revealed through Gabriel to the Prophet Muhammad. According to early traditions, Gabriel brought the Qur’

n (Koran), the sacred scripture of Islam that contains, in Muslim belief, the word of God revealed through Gabriel to the Prophet Muhammad. According to early traditions, Gabriel brought the Qur’![]() n directly to the Prophet’s heart, suggesting an emotional rather than intellectual transference. Gabriel is represented on the Qur’

n directly to the Prophet’s heart, suggesting an emotional rather than intellectual transference. Gabriel is represented on the Qur’![]() n as a spirit whom the Prophet could sometimes see and hear. Apparently, the revelations occurred in a state of trance, accompanied by heavy sweating. They carried their own conviction, strong enough to split a mountain from fear of God, according to the scriptures themselves. The Qur’

n as a spirit whom the Prophet could sometimes see and hear. Apparently, the revelations occurred in a state of trance, accompanied by heavy sweating. They carried their own conviction, strong enough to split a mountain from fear of God, according to the scriptures themselves. The Qur’![]() n describes itself as the transcript of a heavenly book written on a preserved tablet with no earthly source.

n describes itself as the transcript of a heavenly book written on a preserved tablet with no earthly source.

The Mountain of Light, near Mecca, where Muhammad first encountered the Archangel Gabriel

It took Muhammad three years before he gained the confidence to preach his revelation to the public at large, although he did explain the message to his family, and even a few close friends, in the interim. A tiny group formed around him, but small though it was, this group proved to be the seed from which the whole of Islam eventually grew. It was not an easy growth. Most influential figures in Mecca rejected the new doctrine, which preached a strict monotheism, opposed idolatry, and consequently threatened trade. At the time, the Ka‘bah was the focus of almost all Arab religious cults and a magnet for lucrative pilgrimages. If the new religion took hold, who could tell what would happen to the Ka‘bah’s favored status? Who could tell what would happen to commerce?

Despite everything, Islam did manage to grow, although opposition increased as its influence spread. Early converts found themselves persecuted and even tortured. But in 619 CE, Muhammad himself underwent his supreme religious experience while spending the night in an open sanctuary attached to the north wall of the Ka‘bah. While traditions vary slightly, there is general agreement that he was transported by Gabriel on a winged horse to the city of Jerusalem. There they went to the rock on which Abraham was prepared to sacrifice his son5 and hence to heaven itself, ascending through higher states of being toward God. At one point, Gabriel told Muhammad he could go no farther because to do so would risk burning his wings in the glory of the Almighty. Muhammad, however, was permitted to continue until, prostrate before the divine throne, he received the ultimate storehouse of Islamic knowledge, including the final form and number of the daily prayers.

The idea of spreading the message of Islam beyond the city of Mecca, something that had been preying on Muhammad’s mind, received an unexpected boost in 621 CE when a delegation arrived from Yathrib, a city to the north, inviting him to take up residence there as civic leader. The following year, the Prophet reached an agreement with the people of Yathrib (now modern Medina), promising leadership in return for protection. He then ordered his followers to travel to Yathrib in small groups to avoid undue attention and await him there. Muhammad himself escaped from Mecca only just in time. His enemies attacked his home, with murderous intent, shortly after he had fled. His arrival in Yathrib on September 25, 622, CE marked the establishment of Islam as a religion and the introduction of the Islamic calendar.

Today, Islam is the world’s second-largest religion after Christianity. According to a study released by the Pew Research Center in 2011, it has 1.62 billion adherents, only a little short of one person in four throughout the world. All follow a lifestyle and belief system arising from the revelations of a spirit voice in an Arabian cave more than thirteen centuries ago.

Islam was not, of course, the first religion to have stemmed from spirit revelations, nor was it the last. But spirits have also had effects that were almost entirely political—and far-reaching. As such it ably illustrates both the direct contemporary influence of a spirit contact and its implications for the course of history, even when those who believe in it are limited in numbers.