![]()

WITH THE ADVENT OF THE RENAISSANCE, SPIRIT INFLUENCE BECAME increasingly overt—although the Inquisition remained brutally active—and the numbers of grimoires in circulation actually increased under the stimulus of Renaissance Neoplatonism. Scholarly investigation of the occult arts and spirit evocation became widespread. This spirit renaissance is felt to the present day, due to the activities of a man who arguably became the world’s second most famous prophet.

Michel de Nostradame was born at St. Remy in France on December 14, 1503, at the stroke of midnight. He was the elder of two brothers and studied mathematics, Greek, Latin, Hebrew, and the humanities at the feet of his maternal grandfather, Jean de St. Remy. He was also taught how to use an astrolabe, an instrument used by astronomers and astrologers for predicting planetary positions, and may have picked up some herbal lore through watching his grandfather—a physician—compounding potions and ointments. When Jean de St. Remy died, the boy moved back to live with his parents at St. Remy-en-Crau and was subsequently sent to the university at Avignon. To gain entrance, he had to pass examinations in grammar, rhetoric, and philosophy. He did so well that his examiners made him a teacher. His father later arranged his transfer to Montpelier Medical School where he remained for three years.

At the time, medical school examinations were conducted by dispute. For his finals, Michel sat from 8:00 a.m. to noon, arguing points of physics and logic with his professors so successfully that he was awarded the scarlet robe of a scholar. But to achieve the status of physician, he had to teach under supervision for three months and then survive a further, more rigorous, examination by dispute. For the ordeal, he presented himself in turn to four different professors, each of whom questioned him about the treatment and cure of a specific illness. This was followed, just over a week later, by a visit to the chancellor, who stuck a pin at random into a huge medical text in order to select the next disease for which the student was to prescribe. When he survived these tests, an aphorism of Hippocrates was selected—again at random—and he was required to prepare a thesis on it for delivery within twenty-four hours. His professors formally disputed his thesis for four hours in the Chapel of St. Michel. A week later, Nostradamus received his license to practice as a physician. Shortly afterward, bubonic plague swept through his native France.

Michel, now known by the Latin version of his name, Nostradamus, began to establish a medical reputation in his twenties when he devised treatments for plague that proved remarkably effective. By the time he was fifty, his name was known throughout Europe. In 1554, there was an outbreak of plague in Marseilles and Nostradamus was called in. Within days he was feted throughout the city as successful cure followed successful cure. The plague, known as the Blue Sickness or Black Death, hit Aix-en-Provence. Months into the outbreak, its parliament had closed down and courts and churches ceased to function. More than half its citizens fled and weeds began to grow in the streets. The city gates were shut and remained closed for a year in an attempt to isolate the disease. After a deputation begged Nostradamus for his help, he took up residence in the stricken city and soon the outbreak began to abate. Grateful authorities loaded him with gifts and voted him a permanent pension. The plague struck at Salon and again Nostradamus was called in. A rival doctor accused him of magical practice. The authorities ignored him and when the outbreak died down, Nostradamus was given more gifts.

By now in middle age, he had become a wealthy man. His first wife was dead for more than ten years and he had fallen in love with another woman, the widow Anne Ponsart Beaulme (née Gemelle). With a strong desire to marry again and settle down to a less hectic lifestyle, he proposed to Madame Beaulme and she accepted. But the less hectic lifestyle proved elusive. He continued his practice of medicine but soon added on a new and very different career, as a publisher. What he published (and wrote) was an almanac.

![]()

The first known almanac appeared in Europe in 1457 and set the style for those that followed. They were typically based around an annual calendar of events and usually contained seasonal tips for farmers. But much of their content was devoted to weather forecasting and other astrological predictions. Nostradamus embarked on his own venture cautiously, publishing a trial edition designed to gauge public reaction. He found himself with an immediate success on his hands, largely due to the predictive four-line poems he had assigned to each month of the year.

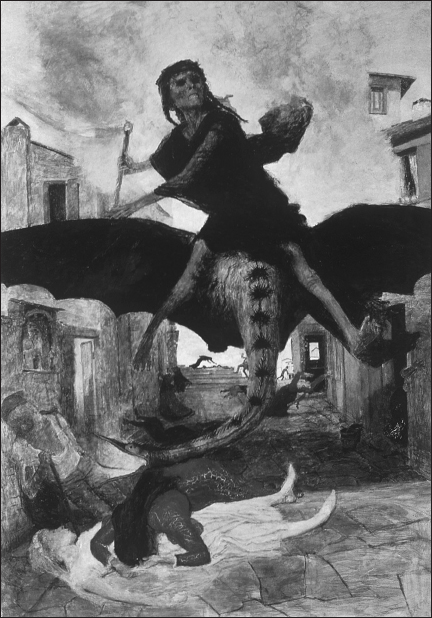

The Black Plague, depicted here as a rampaging demon, first ushered the prophet Nostradamus into public prominence when his remedies proved effective against the disease.

Emboldened by his success, Nostradamus turned the almanac into an annual. His work on the publication seems to have given him a taste for prophecy, for he began to write a book called Les Propheties containing Centuries and Presages devoted to his predictions for a more distant future. Like the poems in his almanac, each presage was written as a quatrain.

The term Centuries refers not to a time period, but rather to a grouping of one hundred prophecies. By his death in 1566, he had written ten Centuries, or just short of a thousand prophecies (since one of the Centuries fell short of the requisite one hundred). His secretary at the time, Jean-Aymes de Chavigny, claims he was afraid of public reaction and kept his prophecies to himself for a long time before publishing them. However, the Lyons printer Macé Bonhomme eventually brought out a first edition in 1555. It contained three Centuries and fifty-three quatrains of a fourth.

The book was an instant success, despite its many obscurities. It was written in a mixture of French, Greek, Latin, and Italian, crammed with anagrams, initials, cryptic terms, and mysterious abbreviations. With few exceptions, the predictions were undated. Nonetheless, the work quickly found its way into influential circles. The French queen, Catherine de Medici, certainly had a copy. The book was issued toward the end of 1555. In the early months of 1556, Catherine wrote to the governor of Provence demanding that Nostradamus be sent to the Royal Court. By the time he received the summons, it was summer. He set out on July 14, 1556, for the court’s summer seat at St. Germain-en-Laye. There Nostradamus had a brief meeting with the king (Henri II) before being closeted for a longer period with Queen Catherine. What happened at these meetings is not known, but Nostradamus obviously impressed the royal couple since he was given a gift of 130 écus.

Nostradamus’s warm reception may have had something to do with an earlier prediction made by the Italian astrologer Luc Gauric. Gauric had forecast Henri’s accession to the throne, a sensational duel in the early part of his reign, and the probability that Henri would lose his life in a similar event. By the time Nostradamus was summoned to court, the first two parts of this prediction had already come true. Henri was now king, and a sensational duel had indeed marked the early part of his reign. It took place between two nobles, Guy Chabot Jarnac and François Vivonne la Châtaigneraie, at St. Germain-en-Laye on June 16, 1547. King Henri attended and watched Châtaigneraie die. A phlegmatic Henri recalled the remainder of the prediction and remarked, “I care not if my death be in that manner more than any other. I would even prefer it, to die by the hand of whomsoever he might be, so long as he be brave and valiant and that I keep my honor.” Catherine took the whole thing a lot more seriously. She called on Gauric to provide more details, and Gauric cast a horoscope that advised the king to avoid all single combat, particularly during his forty-first year, since he would be particularly susceptible to a head wound that would certainly blind him and might even cost him his life.

With this ominous prediction hanging over her husband, Catherine discovered that Nostradamus had, in his very first Century, written the quatrain:

Le lion jeune le vieux surmontera

En champ bellique par singulier duelle

Dans cage d’or les yeux lui drevera

Deux classes une, puis mouris, mort cruelle.

(The young lion will overcome the old one,

On the field of battle, by means of single combat

In a cage of gold his eyes will be pierced.

A double wound, a cruel death.)1

King Henri’s emblem was the lion, and it occurred to the queen that Nostradamus was also predicting the king’s death in a duel. Others came to a similar conclusion. At one point, the quatrain was so widely discussed at the French Court that the English ambassador alerted Queen Elizabeth I. When, three years later, Henri was indeed killed in single combat during a jousting accident that cost him the sight of one eye before he finally succumbed, Nostradamus’s reputation as a prophet was firmly established. No one had the slightest doubt that this was the event he had foretold. As news spread, an angry crowd stormed through the Paris streets to burn him in effigy and demand he be turned over to the Inquisition on charges of sorcery. Only Queen Catherine’s intervention saved him.

Despite the immediate reaction, Nostradamus’s influence spread. All sorts of stories began to circulate about his prowess as a seer. One recounted how a servant of the wealthy Beauveau family lost a valuable hound that had been left in his care and called on Nostradamus to help him find it. Nostradamus was in his study, determined not to be disturbed, but after a time the noise of the man’s knocking got too much for him. He opened an upstairs window and, without waiting to find out what the problem was, shouted down, “You’re making a lot of noise over a lost dog—look on the Orleans Road: you’ll find it there on a leash.” According to the story, the servant subsequently found the dog where Nostradamus had predicted he would.

Nostradamus’s reputation provoked challenges. On one occasion he was a guest at Fains Castle in Lorraine when his host, the Seigneur de Florinville, defied him to predict the fate of two pigs in the farmyard. Nostradamus told him the black pig would be eaten by the seigneur, while the white one would be eaten by a wolf. According to the story that circulated afterward, the seigneur issued secret instructions to his cook that the white pig should be slaughtered and served to his guests that night at dinner. When the pork was carried in, de Florinville remarked that no wolf was likely to get the white pig now since they were about to eat it, but Nostradamus insisted they were actually about to eat the black pig. His host then summoned the cook and invited him to prove Nostradamus wrong. But the embarrassed cook explained that while he had started to roast the white pig as instructed, a pet wolf cub belonging to one of the castle guards had stolen the meat off the spit. Not wanting to disappoint his lordship’s guests, the cook then killed the black pig, which the guests were now about to eat.

Another story about Nostradamus came closer to genuine prophecy. While in Italy, he was on the road near Ancona when he met a group of Franciscans. To the astonishment of the monks he threw himself at the feet of one of them—a young friar named Felice Peretti—and addressed him as “Your Holiness,” a term reserved for the pope. In 1585, less than twenty years after Nostradamus’s death, Peretti became Pope Sextus V.

While it is possible, perhaps even likely, that these stories are apocryphal, there is no doubt at all about his influence. Both his book and the ongoing prognostications in his almanac—a total of more than six thousand predictions—spread his fame throughout France and led to requests for horoscopes and psychic consultations from members of the nobility and various influential people inside the country and beyond. After his death in 1566, his fame and influence actually increased. His prophecies remain in print to this day and have been translated into every major language of the world. During World War II, Nostradamus’s prophecies (some faked, all skewed in their interpretation) became part of the Allied propaganda effort to diminish Nazi morale. Following the 9/11 attack on New York’s Twin Towers, Nostradamus predictions of the event—many highly suspect—flooded the Internet.

Despite an interest that has endured for centuries, very few people are aware of the source of Nostradamus’s prophecies. When the question arises at all, most will readily accept the prophet’s own claim that he had used only “judicial astrology”—a perfectly respectable art in his day—to produce them. But there is clear evidence that Nostradamus was lying when he made this claim. He was not even a particularly good astrologer: the surviving charts he drew up contain numerous errors.2 The reason for his deception seems to have been fear of the Inquisition. Scholarly detective work has shown that the predictions were dictated to him by a spirit—and one that he evoked by means of magical ritual.

The first clue emerges in a document known as the Epistle to César, a public letter to his son, no more than a few weeks old at the time, which appeared as the preface to the first edition of his Centuries. Here Nostradamus wrote:

And further, my son, I implore you not to attempt to employ your understanding in such reveries and vanities which wither the body and bring the soul to perdition, troubling the feeble sense: even the vanity of that most execrable magic, denounced already by the Sacred Scriptures and by the Divine Canons of the church—from which judgment is excepted judicial astrology, by means of which, and the divine inspiration and revelation, by continual calculations we have reduced our prophecies to writing. And, not withstanding that this occult philosophy was not reproved by the church I have not wished to divulge their wild persuasions, although many volumes which have been hidden for centuries have come before my eyes. But dreading what might happen in the future, having read them, I presented them to Vulcan, and as the fire began to devour them the flame, licking the air, shot forth an unaccustomed brightness, clearer than natural flame, like a flash from an explosive powder, casting a strange illumination over the house, as if it had been in sudden conflagration so that none might come to be abused by searching for the perfect transmutation, lunar our solar, or for incorruptible metals hidden under earth or sea, I reduced them to ashes.3

Although Nostradamus begins the epistle with the familiar claim that his prophecies were astrologically generated, in the second half of the quoted passage he admits to having owned “many volumes” of occult lore. The nature of these books is clear from his references to transmutation and incorruptible metals. They were works on alchemy and magic. He burned them, of course, but not before he read them. Even their destruction underlines their magical nature—they produced an unnatural flame. What were these books? Part of the answer may lie in the very first quatrain Nostradamus ever published outside of his almanac—Quatrain 1, Century 1—which reads:

Étant assis de nuit secret étude,

Seul, reposé sur la selle d’airain,

Flamme exigue sortant de solitude

Fait prospérer qui n’est pas croire vain.

(Being sat secretly at night in his study,

Alone, on the saddle of brass,

A small flame emerges out of the void

Causing a vain believe)4

This was followed by:

La verge en main mise au milieu de Branches

De l’onde il mouille & le limbe & le pied:

Un peur & voix frémissent par les manches:

Splendeur divine. Le Divin pres s’assied.

(Grip the Branchus wand in the middle

Wave it to wet the hem and the foot:

A voice quivering with fear:

Divine splendor. The Divine sits near.)5

It is worth noting that these verses echo, almost word for word, a passage in De Mysteriis Egyptiorum (“Concerning the Egyptian Mysteries”), which reads:

Foemina in Branchis fatidica, vel sedet in axe, vel manu tenet virgam, vel pedes aut limbum tingit in aquam et ex his modis impletur splendore divino, deumque nacta vaticinatur.

(The prophetess of Branchus sits wand in hand, places her foot and the hem of her robe in the water and in this way creates the divine splendor and calls the god by whom she prophecies.)6

De Mysteriis Egyptiorum was written by the Neoplatonic philosopher Iamblichus (or possibly a member of his school) somewhere around the third century CE. It deals with a type of “higher magic” operating through divine agencies. Much of the text is concerned with the ritual evocation of gods, demons, and other spirits.7

The similarity between the text and Nostradamus’s opening quatrain is no coincidence. Further investigation of the prophecies shows that the conjuration of spirits was definitely one of his interests. The forty-second Quatrain of the first Century, for example, points to this as well as to familiarity with another magical tome:

The ten Calends of April, according to Gothic measure,

Are revived again by wicked people

The fire goes out and the devilish assembly

Looks for the bones of the Psellus demon.

The “Psellus” mentioned in the final line is Michael Psellus, the Byzantine philosopher, theologian, statesman, and Neoplatonist. His “demon” was a work he wrote in the eleventh century called De Demonibus (“About Demons”), which contained the following instructions for spirit conjurations:

The diviners take a basin full of water appropriate to the use of the demons. This basin full of water seems first to vibrate as if it would emit sounds nevertheless the water in the basin does not differ in appearance from natural water, but it has the property, by the virtue which is infused into it, of being able to compose verses which renders it eminently apt to receive the prophetic spirit. For this sort of demon is capricious, earthbound and subject to enchantments and so soon as the water begins to give out sounds, manifests its satisfaction to those who are present by some words still indistinct and meaningless, but, later, when the water seems to boil and spill over, a faint voice murmurs words which contained the revelation of future events.8

Here again, it is no coincidence that the final five words of the instructions link the conjuration to prophecy, as does Psellus’s earlier reference to “prophetic spirit.”

The two quatrains quoted earlier that begin the Nostradamus Centuries are not themselves prophecies. Instead, consensus scholarship has now concluded that they are descriptions of how his prophecies came about. The translation of Quatrain 1 is as follows:

Seated by night in secret study

Alone resting on the brazen tripod

As slender flame licks out of the solitude

Making possible what would have been in vain.

This was followed by Quatrain 2 :

The rod in his hand is placed in the center of Branchus

He moistens the hem of his robe, his limb and his foot

A voice causes his arms to tremble with fear

Divine splendor. The God sits close beside him.

What is being described here is a rite—and not any of the familiar Church rites to which Nostradamus so ostentatiously subscribed. Taken together, the verses summarize an extraordinary ceremony that involved a magical rod or wand, a brass tripod, a naked flame, and the appearance of a god in the midst of divine light: in other words, a ritual of evocation.

On the evidence of the quatrains alone, it would seem that the works of Psellus and Iamblichus were among the tomes “hidden from ancient time” that Nostradamus felt constrained to destroy. The “Branchus” referred to here—and in the Egyptian Mysteries of Iamblichus—is Branchus of Miletus (in what is now Turkey), a figure in Greek mythology who was fathered on a human woman by the sun god Apollo during a miraculous act of fellatio. The boy was walking in the woods one day when he met with his heavenly father and, struck by the god’s beauty, kissed him. The result of this impulse was that Branchus was instantly endowed with the gift of prophecy.

Based on this myth, the Greeks established an oracular temple jointly dedicated to Branchus and Apollo at Didyma, south of Miletus. The sanctuary was in charge of the Branchids, a group of priests named after Branchus himself, and the prophecies generated there were reputed to have been a heady mix of inspiration and madness.

The Branchids seem to have betrayed their trust, for they were reputed to have collaborated with the Persian king Xerxes when he plundered and burned the temple in 494 BCE. Persians and priests both fled to Sogdiana, an ancient Asian country centered in the Zeravshan River valley, in what is now Uzbekistan. But the sacrilege caught up with their descendants when Alexander the Great conquered the country with considerable slaughter in 328 BCE. Another of Alexander’s conquests, that of Miletus itself in 334 BCE, resulted in the oracle being resanctified. Due to the memory of their betrayal, no new Branchid priests were ordained. Instead, the oracle was administered by the municipal authorities who elected a prophet on an annual basis. Around 300 BCE, the Milesians began work on a new temple of Branchus planned to be the largest building in the Greek world but archaeological excavations in the early twentieth century showed it was never finished.

Iamblichus described the temple ceremony in these words:

The prophetess of Branchus either sits upon a pillar or holds in her hand a rod bestowed by some deity, or moistens her feet or the hem of her garment with water, or inhales the vapor of water and by these means is filled with divine illumination and, having obtained the deity, she prophesies. By these practices, she adapts herself to the god, whom she receives from without.

Elsewhere in his works, he mentions that the priestess at Delphi sat upon a tripod in order to receive a “ray of divine illumination.” Nostradamus mentions a tripod in his quatrains. He also wrote in his Epistle to César that the intellect could perceive nothing of the occult “without the aid of the mysterious voice of a spirit appearing in the vapor floating above the vessel of water and without the illumination of the magic flame in which future events are partly revealed as in a mirror.”

It is clear from this textural evidence that Nostradamus was indeed interested in magic, an interest prudently well-hidden in the era of the Inquisition. By his own admission, he studied magical books, and while he suggested they were works on alchemy, the content of his own quatrains indicates that some were rituals of evocation linked to the art of prophecy. All of the evidence points to the Nostradamus prophecies being spirit driven.

This conclusion is reinforced by another of the stories attached to his legend. According to Hollywood-born author John Hogue,9 the widowed Catherine de Medici summoned Nostradamus to the Château Chaumont in 1560 and demanded further insights into the future. On this particular visit, the prophet elected not to carry on his pretense about judicial astrology and instead requested the use of a large room in which he would not be disturbed. There he traced a magic circle on the floor, fortifying it with holy names of power and angelic sigils. Before it he set up a magic mirror, a black concave surface of polished steel, the corners of which were traced in pigeon’s blood with the names YHVH, Elohim, Mitratron, and Adonai. At the stroke of midnight the queen entered the dimly lit chamber, filled by this time with clouds of incense smoke. Nostradamus led her into the magic circle, then began an invocation to the angel Anael, a spirit believed to grant prophetic visions.

The vision granted on this occasion was of a room that somehow abutted the chamber in which they stood. Standing in it was Francis II, the queen’s son. He walked once around it, then abruptly vanished. Nostradamus interpreted this as the boy’s impending death. Another of the queen’s children appeared, the boy who would become Charles IX. He circled the room fourteen times; Nostradamus predicted that he would rule for fourteen years. Then came the future Henri III, who walked around the room fifteen times, then François, Duke of Alençon, whose image was quickly transformed into that of Henry of Navarre, the man to whom Catherine was destined to marry her daughter Margot.

The interest of this story is not in the predictive accuracy of the vision—which may be the result of later embellishments—but in the fact that Nostradamus was thought to be so intimately involved with the highest in the land that he could safely conduct this necromantic experiment. The perception is largely correct. Nostradamus clearly did have friends in high places, friends who came to him for advice and were thus exposed to spirit influence one step removed. A similar situation existed in England, where an influential courtier also had the ear of his queen … and also communicated with spirits.