![]()

THERE ARE CURIOUS PARALLELS BETWEEN PRE-REVOLUTIONARY FRANCE and pre-Revolutionary Russia. Like Louis XVI, Tsar Nicholas II was fundamentally weak, pleasant enough in his personal relationships, but lacking in political insight. Like Louis, Nicholas was the last in a centuries-long line of absolute monarchs, and both had an almost fatal instinct for meddling in political affairs they did not understand while remaining blind to the dynamic social changes that were about to topple their thrones. These two monarchs vacillated on the vital question of establishing a workable parliament, and married foreigners who, like themselves, lacked political sense yet insisted on interfering with the political life of their adopted countries. Both were imprisoned at the end, both executed by their former subjects. There were similar rumors that one member of the two royal families had managed to escape. Finally, both imperial courts had their resident magician. In France, it was the mysterious Cagliostro, in Russia the shamanistic Rasputin. These magicians had many similarities themselves; they were both born of peasant stock, they both lost a parent in childhood, and they both exhibited second sight. Most important, both were in contact with spirits.

The history of pre-Revolutionary Russia is inextricably linked with the Romanov dynasty, an aristocratic family of little grandeur until the day in 1613 when sixteen-year-old Michael came to the throne in his troubled homeland. Contemporary records show he accepted his election with enormous reluctance, yet he nevertheless established a ruling lineage that lasted nearly three centuries. Members of the family were highly religious. According to the Romanovs’ biographer E. M. Almedingen:

The early Tsars were almost continually in attendance on the heavenly hierarchy and the business of governing was interwoven with the business of the Church. They ordered their year in strict accordance with the memorials left by the Lord, the Lord’s Mother and the company of saints. The Tsars’ work and leisure, their clothes and food, even their gait and demeanour were all patterned in conformity to what they believed to be God’s will for them. Their wives never shared their board, and could share their bed only on such nights as were sanctioned by the church ordinance. The season of Lent and all the lesser fasts enjoined continence. So did all the great feasts since their honour would have been polluted by sexual intercourse.1

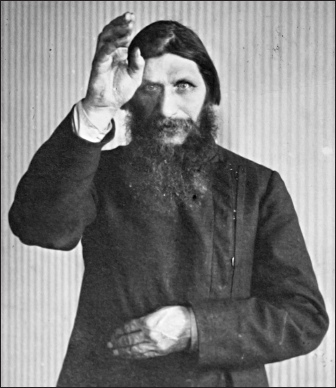

Grigory Rasputin, whose spirit contacts and mystic abilities gave him enormous power over the Tsar and Tsarina of prerevolutionary Russia

Tellingly, Ms. Almedingen adds that the rigor practiced in the seventeenth century “had not altogether vanished in the 20th.” By the time the twentieth rolled around, Tsar Nicholas II was occupying the Russian throne during a period of internal turmoil almost unequaled in the history of his country. But a new and strange factor had entered the picture. It was neatly summed up in a caricature by the artist Ivanov that showed a tiny tsar and tsarina seated like children on the lap of a towering Russian peasant, with grim features, deep-set, hypnotic eyes, and a long, black beard. The cartoon was satirically captioned RUSSIA’S RULING HOUSE. The peasant was Rasputin.

Grigory Efimovitch Rasputin was born, probably in the late 1860s, in the small Siberian town of Pokrovskoe. His father was a horse owner who worked as a coachman and was relatively well-to-do. In many ways, the young Rasputin was a very ordinary child. He loved horses, adored the life of the sweeping steppe, and hated schooling, of which, as it happened, he received very little. But one strangeness manifested early—he had “second sight,” a catchall term for a wide-ranging psychical ability that includes an awareness of spirits.

Perhaps the earliest manifestation of his talent came before the age of twelve while he was ill with fever. A horse had been stolen in the village and a number of men gathered at the home of Rasputin’s father (who was then village headman) to discuss the matter. During the course of the meeting, the boy sat up and flung an accusation at one of the peasants. He was not immediately believed—his father took some pains to placate the accused man—but two of the gathering were intrigued enough to investigate. They subsequently discovered that the thief was the man Rasputin named. In another example of his odd abilities, his daughter Maria has described how, as an adult during his days in St. Petersburg, her father was instantly able to detect a revolver concealed in a woman’s hand-warmer—and possibly saved himself from assassination by doing so.

There was epilepsy in the family, a disease associated in shamanic cultures with an ability to speak to spirits. Rasputin’s sister had it, and later his son did too. The sister was likely killed by a seizure; she fell into a river while washing clothes and drowned. It was a bad period for Rasputin in an otherwise happy childhood, for his mother and brother also died around this time and the family home was razed to the ground by fire. Rasputin survived the multiple tragedies to build up, during his teens, a reputation as a libertine. His approach, to judge from his behavior in later life, was direct in the extreme. Urged on by a monstrous libido—a more commonplace characteristic in mystics than one might imagine—he would often attempt to undress a woman during the first few minutes of their meeting. It is a tribute to the dynamism of his personality that many women did not bother to resist.

But sexual hedonism was not the only aspect of a complex character to manifest in those early years. Colin Wilson, who has written one of the better biographies of Rasputin,2 remarks that he was “driven by a will to power that was stifled in Pokrovskoe.” Perhaps a more complete assessment might be that he was driven by a will to occult power, for the occult was to become a central pivot of his life.

At the age of sixteen, Rasputin had occasion to visit the monastery of Verkhoture and stayed for four months. During that time he came into contact with an heretical sect of flagellants, the Khlysty, who held the belief that the kingdom of God could be attained on earth, at least by an elite. It is not known whether Rasputin practiced Khlysty techniques, although he was certainly drawn to their doctrines. But if he did, there is a chance the techniques opened the doors of his mind to visionary experience. Aldous Huxley, in his twin essays, The Doors of Perception and Heaven and Hell,3 had much to say with a bearing on this point. Although Huxley’s literary springboard was an experiment with mescaline, he makes the point that drugs are not the only means of influencing body chemistry toward mystical or pseudo-mystical experience. Such practices as flagellation, especially when the wounds are left unwashed and untreated, lead to a buildup of decomposing protein in the bloodstream, along with bacterial infections. This can, in certain circumstances, produce biochemical changes that influence brain function. Visions may follow. Nor was Huxley entirely satisfied that such visions were subjective hallucinations. He felt they might actually represent deeper insights into the nature of reality.

At the monastery, Rasputin also met the holy hermit Makary, whose blessing was eagerly sought by pilgrims. Makary, it seems, sensed something extraordinary in this brawling youth and took the trouble to advise him about his future. Whether he accepted this advice is open to question, for on leaving the monastery, Rasputin promptly returned to his old ways, drinking, whoring, and keeping a shrewd eye out for ways to grab another ruble—not all of them honest, as his brief imprisonment in 1891 attests.

About a year earlier, Rasputin had married Praskovie Fedorovna Dubrovine, a slim, blond, docile girl from a neighboring village. She subsequently bore him a son. But the baby died within six months and Rasputin underwent a change of character. He revisited Makary to discuss the meaning of death and began to study holy books and pray. In the spring, while plowing his fields, the upsurge of piety was rewarded with a vision of the Virgin Mary, who, he claimed, communicated something of great importance to him. Rasputin planted a cross to mark the spot, told his family of the vision, then went quickly to Makary for an explanation. The hermit advised a pilgrimage to strengthen his spiritual power. Rasputin agreed and, with the sort of determination difficult for the irreligious to comprehend, set out to walk the two thousand miles to one of Europe’s oldest monastic communities at Mount Athos in Greece. But he was not impressed by the character of the monks when he got there and declined to become a novice. Instead, he decided to press on with his pilgrimage and walked a further thousand miles across Turkey to the Holy Land.

On his way home, Rasputin visited Kazan and called at the cathedral. Here he had an experience that moved him profoundly. His vision of the Virgin had been unusual in that she was not dressed as the icons in the local churches represented her. Rasputin had filed this fact away in his mind without being able to explain it. Now, in Kazan Cathedral, he was suddenly faced with a representation of the Virgin exactly as he had seen her in the fields. If ever he needed a justification for his pilgrimage, this must surely have been it.

The round-trip took him more than two years, and he returned home so changed that his own wife did not recognize him. Like many another magi, his wanderings had brought him a strange personal power and it communicated to the villagers. When he built an oratory in his backyard and began to hold prayer meetings in his house, they came in droves. A jealous village priest, Father Peter, suspected heresy and reported him to the bishop of Tobolsk. Subsequent investigations unearthed nothing unusual, but if Rasputin’s outward observance was orthodox, the man himself was not. He had an intense hypnotic ability and appears to have developed impressive powers of healing. He was reputed to be able to expand and contract the pupils of his eyes at will, a trick that must have contributed greatly to the dominance of his gaze.

Wanderlust remained strong in him and he seemed unable to settle down again to village life. For a decade he traveled throughout Russia, building up his reputation as a holy man and healer. He returned home infrequently, but even in Pokrovskoe the people learned he had become a prophet, with his second sight so highly developed that it was impossible to fool him.

There are times in the history of nations when it is dangerous to exhibit psychic powers, for one runs the risk of burning, but there are also times when psychic powers become chic and fashionable, and one is perhaps in even greater danger—of becoming a pet to the rich and powerful. At the turn of the century, this was the situation in Russia. High society in St. Petersburg exhibited a fascination for astrology, magic, fortune-telling, and Spiritualism. Among the most enthusiastic adherents was the Grand Duchess Militsa, who at one time seems to have led the tsarina herself to engage in table-tapping. (The tsarina’s spiritual directors disapproved and she abandoned the practice.) It was the Grand Duchess, always searching for a new purveyor of miracles, who discovered Rasputin and invited him to St. Petersburg. He accepted in 1903.

The visit brought him into contact with the tsarina’s confessor, Father John Sergeieff. Despite the priest’s unease about psychical phenomena, the two got along famously, probably because they shared the same ultraconservative political views. This fact may have contributed to Rasputin’s ready acceptance at court, although that was still some time in the future. It is entirely possible that the real turning point came when, during the canonization ceremonies of a monk named Seraphim, he predicted (accurately) that an heir to the Russian throne would be born within a year. But it was a further two years before he met the imperial family and embarked on a period of his life that was to make him the most influential man in Russia.

Rasputin returned to St. Petersburg in 1905 and was warmly welcomed by Grand Duchess Militsa. In a curious atmosphere where almost anything could happen, Rasputin cured a dog belonging to Militsa’s brother-in-law, and the Grand Duke responded by paying for Rasputin’s wife to come to St. Petersburg for an operation. But the broad-shouldered Siberian peasant was not the type to become a pet to anyone. His success did not depend on patronage. Within a short time, his name had become known throughout the city and crowds were literally queuing up to see him. He caused the lame to walk, cured the sick, and, according to one report, magically transformed a handful of earth into a blooming rose. On November 1, he met the tsar, who described him in his diary as “a man of God.”

There is considerable controversy about the circumstances of this first meeting. Several biographers suggest Rasputin was dancing drunkenly at a gypsy encampment when a messenger arrived with news that the tsar’s son was ill. Rasputin then cured the boy, partly by distant prayer and partly by some on-the-spot faith healing. At least one source claims he was called out from church by his friend Father Sergeieff, who had by this time become convinced of his therapeutic skills. In fact, it seems unlikely that anything very spectacular happened on this occasion and it is just possible that his healing abilities were not even involved. But if this was the case at first, circumstances changed radically in the years ahead.

The pivot of Rasputin’s influence over the Russian royal family was the condition of the tsarevitch, the little boy whose birth he had foretold. The tsarevitch suffered from hemophilia, a blood disease inherited from his maternal grandmother, Queen Victoria. The condition prevents normal clotting. As a result, the slightest injury—even bruising—can lead to internal bleeding that, unless halted artificially, results in death. In 1907, the boy fell seriously ill and Rasputin was called, since court physicians appeared helpless. Almost instantly, the tsarevitch began to recover. The whole incident had such inherent drama that Rasputin was promptly accepted as a miracle worker. He became a daily visitor to the palace, impressing the tsar with his powers and engendering in the tsarina an emotion falling little short of worship. Neither his tactless habit of calling on her four teenage daughters in their bedrooms, nor his seduction of the children’s nurse, shook the tsarina’s faith in Rasputin as a holy man. Nor can one entirely blame her, for Rasputin’s abilities were impressive. In September 1912, for instance, while Rasputin was away from St. Petersburg and the royal family were holidaying at Belovetchkaya, the tsarevitch developed hemorrhage and blood poisoning following a boating accident. When fever set in, the tsar’s doctors feared for the boy’s life, but the tsarina telegrammed Rasputin at his native Pokrovskoe, almost two thousand miles away. Instead of hurrying to the child’s side, Rasputin merely sent a telegram back, remarking that the illness was not so serious as the doctors imagined. When the message arrived, the boy began to recover. Nor were his powers confined to healing. Two years earlier, while visiting his friend (and later his enemy) the monk Illiodor, Rasputin successfully carried out two exorcisms on women apparently possessed by demons.

But from about 1912 onward, Rasputin’s second sight—or possibly his common sense—seems to have made him increasingly aware of the grim fate in store for his royal patrons. He prophesied that the throne would be safe only so long as he himself lived. In December 1916, with the prevision of his own death hanging heavily over him, he wrote a remarkable document in which he said, among other things:

I feel that I shall leave life before January 1 … If I am killed by common assassins, and especially by my brothers the Russian peasants, you, Tsar of Russia, have nothing to fear, remain on your throne and govern, and you, Russian Tsar, will have nothing to fear for your children, they will reign for hundreds of years in Russia. But if I am murdered by Boyars, nobles, and if they shed my blood, their hands will remain soiled with my blood, for twenty-five years they will not wash their hands from my blood … Tsar of the land of Russia, if you hear the sound of a bell that will tell you that Grigory has been killed, you must know this: if it was your relations who have wrought my death, then no one in the family, that is to say, none of your children or relations, will remain alive for more than two years. They will be killed by the Russian people … I shall be killed. I am no longer among the living.4

This fateful prophecy came true among circumstances as bizarre as any in the life of the man who made it. Rasputin’s assassin did, indeed, prove to be a member of the nobility, Prince Felix Yusupov, a handsome homosexual with, to judge from his photograph, a striking resemblance to the silent movie actor Rudolf Valentino. Yusupov issued an invitation for Rasputin to visit him in his palace on the night of December 29 and, despite warnings from friends and his own precognitive forebodings, Rasputin agreed to go.

Details of the midnight visit are reminiscent of a horror movie. Yusupov, according to his own testimony, prepared a basement room with bottles of wine and a chocolate cake liberally laced with cyanide, a poison so virulent that it paralyzes in less than a minute and kills in less than four. Some of the wineglasses also had a sprinkling of powdered cyanide. Rasputin arrived at midnight, to the strains of a gramophone playing “Yankee Doodle.” He was brought to the basement room where, again, according to Yusupov, he drank the poisoned wine and ate some of the poisoned cake, ingesting perhaps an ounce of cyanide in the process. It should have killed him instantly—as little as an eighth of an ounce is normally fatal—but, instead, he grew convivial and requested Yusupov to sing. Yusupov, who had a healthy respect for the magician’s “demonic powers,” excused himself and went upstairs to his fellow conspirators with the news that the poison had not worked. They discussed the possibility of strangling their victim but abandoned the notion in favor of shooting him. One of the men gave Yusupov a revolver and he returned to the basement. Rasputin was seated with his head slumped, complaining of sickness and a burning sensation in his throat. Yusupov suggested he should pray before a crystal crucifix in the room, and when Rasputin turned to it, Yusupov shot him in the back. A doctor among the conspirators examined him and pronounced him dead. Two of the conspirators left the palace. The remaining two, which included Yusupov, went back upstairs, leaving the corpse in the cellar.

Yusupov was not happy. At the back of his mind may have been the suspicion that this miracle worker could be capable of the greatest miracle of all—rising from the dead. He went back to look at the body. It was still there. Unconvinced by the evidence of his own eyes, Yusupov leaned over to shake it. Rasputin arose and tore an epaulette from his shoulder. The terrified Yusupov fled upstairs, but Rasputin followed, crawling on all fours. Somehow the “revived corpse” exhibited almost superhuman strength, bursting through a locked door to reach the outside courtyard. Another of the conspirators, Purishkevich, raced after him and fired four times with his revolver. Two shots hit Rasputin and he collapsed again. Purishkevich promptly kicked him in the head and a little afterward, Yusupov battered the body with a heavy steel press.

Incredible though it may seem, later evidence shows Rasputin was still alive at this time, although certainly unconscious. Taking no chances, the conspirators tied his hands, then carried him to a nearby river, where they dumped him through a hole in the ice. The freezing water revived him, for he actually managed to get one hand free and make the sign of the cross. But he was unable to break through the ice on the river and drowned.

This, then, was the man who advised the Russian leadership through one of the most critical periods of Russian history—an occultist so powerful he proved almost impossible to kill, a member of the esoteric Khlysty, a mystic with proven abilities to stare across the vista of the future, a channel for mysterious healing forces effective over thousands of miles, and a visionary who listened to spirit voices. We know too that the tsar and tsarina were not averse to listening to such voices, either indirectly through the advice of Rasputin or directly in their own experiments. In the early years of the tsar’s reign, he constantly evoked the shade of his father for political advice, and a rumor persists that he actually went to war with Japan under the promptings of spirit messages.