![]()

THE VICTORIAN YEARS IN BRITAIN WERE AN AGE OF CONTRASTS. THESE were most obvious in the sexual sphere. Englishwomen of the eighteenth century were described by one shocked Continental historian as “much given to sensuality, to carnal inclinations, to gambling, to drink and to idleness.” But by the time Victoria was firmly established on the throne, the image had changed. Respectability was the order of the day. A woman’s place was in the home and the highest expression of her femininity was motherhood. Despite this, she was simultaneously desexualized, as if childbirth were unconnected to intercourse. Every effort was made to hide the fact that women had legs. They might, for all that was apparent from the fashions of the day, have moved on wheels from the waist down. Necklines rose until they clung modestly around the throat.

The contrast was even stronger in other spheres. The Victorian age saw science emerge from its beginnings as a plaything of the aristocracy to become the system of human thought that would eventually encompass the universe. By the time Darwin published his evolutionary thesis, the world was ready for it. There was, of course, great controversy and opposition. But this in itself was an indication of interest—a really unpopular theory is simply ignored.

Victorian science was essentially materialistic, a mechanistic discipline with both feet firmly planted on the ground. Some scientists actually saw an end to their work. Everything could be weighed, measured and categorized; and it had to be only a matter of time before everything actually was. Within this image of the sober Victorian scientist (an image just as strong as that of the sober Victorian puritan), questions of spirituality were considered superstitious and handed over to those bumbling bishops so often lampooned in Punch.

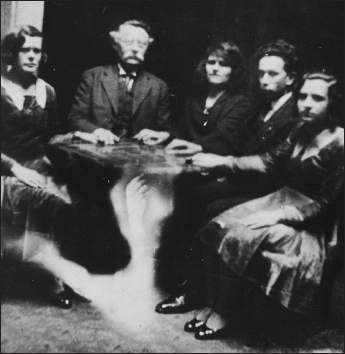

Spiritualism, based on séances of this type, became a worldwide movement during the Victorian era.

Yet underneath the rationalism, there was a feeling of unease. God had been dismissed from his universe and left a yawning chasm. It was a chasm that was destined to be filled, at least partly, by the spirit world. The first Spiritualist medium arrived in Britain in 1852 and excited enormous interest. A year earlier, Cambridge University’s Ghost Club had been formed to investigate supernatural phenomena. In 1882, an even more respectable investigatory body came into being with the formation of the Society for Psychical Research. Fascination with the occult spread like an epidemic. In 1855, the most spectacular medium of all time, Daniel Dunglas Home, arrived in Britain from America and dominated the spiritualistic scene for fifteen years. During this era too, the remarkable Russian Helena Petrovna Blavatsky first set foot on British soil. At first she too dabbled in Spiritualism but soon began to preach her own brand of occultism, Theosophy. She claimed to have learned forbidden arts at the feet of Tibetan masters, whom she still served.

Some of the most popular books of the day were concerned with the occult—a barometer of public interest. Blavatsky’s Isis Unveiled and later her Secret Doctrine were snapped up by enthusiastic readers, despite the difficulties of their content.1 Dickens published his famous Christmas Carol, dealing with the return of Marley’s Ghost. Bulwer Lytton, the aristocratic occultist, produced The Haunters and the Haunted, followed by his even odder The Coming Race, which introduced vril power to the world and influenced Nazi philosophy a century later. Eliphas Levi, the French magus, visited London and was persuaded to perform an evocation of the shade of Appolonius.2 With such a floodtide running in the country, it was not surprising that the queen herself grew interested.

Victoria was eighteen years old on her accession to the throne in 1837, a young lady with so simple an upbringing that she had never had a room of her own. But she was obstinate and strong-willed, two characteristics that were to remain with her until the day she died. Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, the man she later married, noted at the time that she “delighted in Court ceremonies, etiquette and trivial formalities.” It was an accurate observation and here again the characteristic remained in evidence throughout her long reign. No one ever approached the queen lightly. No one, that is, except John Brown.

Brown, a dour, bearded Scot, made his mark in the British court after the death of Albert, the queen’s beloved Prince Consort. On the face of it, Brown seemed an unlikely character to wield influence over Victoria, yet wield it he did. He had the run of the palace and, unlike prime ministers and heads of state, had instant access to the royal presence. Brown appalled the courtiers by his rough-and-ready manners; and laid claim to a minor place in history by the way he spoke to the queen. He seldom used the term “Your Majesty,” but instead would address her simply as “Woman”—“Get on that horse, Woman” … “Mind your step, Woman” … and so on. The mystery was that Victoria, who laid enormous stress on formality, should put up with this treatment for an instant. She would certainly never have accepted it from her favorite prime minister, Benjamin Disraeli, who had to manipulate her with oily flattery. Nor would she have accepted it from members of her own family. To the queen, decorum was everything and the person of the monarch sacrosanct. Yet Brown was permitted his familiarities; and when he died, a few years before Victoria herself, she claimed she had lost her only real friend in the world. She even ordered a statue to be erected in his memory.

Brown was not popular at court. The Prince of Wales, Victoria’s eldest son Edward, nursed a particular loathing for him and on his own accession to the throne had the statue torn down. The dislike may have been a matter of jealousy, for Edward’s relations with his mother were often strained, but if Edward’s reaction is easily explained, the nature of the relationship between John Brown and the queen was more mysterious. Contemporary gossips were so intrigued that they concluded Brown must have made Victoria his mistress—she was referred to behind her back as “Mrs. Brown”—but this is unlikely in view of her character and the enormous love she had for her husband, which if anything actually increased after his death. More to the point, there is no real evidence to support the view. A more likely explanation is that Brown’s hold over Victoria may have been rooted, like the hold of Rasputin over his tsarina, in the shadow world of spirit contact.

Like so many of her subjects, Victoria was caught up in the wave of Spiritualistic practice that swept over her country during the early years of her reign. Buckingham Palace was the setting for a number of séances, and both the queen and her consort engaged in table-turning and similar experiments. Psychics and mediums were presented to Victoria, who showed an enthusiastic interest in their talents. One such individual was the clairvoyant Georgiana Eagle, who demonstrated her powers before the queen at Osborne House, on the Isle of Wight, in July 1846. The queen was so impressed that she had a watch inscribed to Miss Eagle for “meritorious and extraordinary clairvoyance.” But the psychic died before the gift could be presented and the watch later went to Etta Wriedt, the American direct voice medium. Against this background, the greatest tragedy of Victoria’s life occurred. Her husband died on December 14, 1861.

Victoria proposed to the dashing Prince Albert in October 1839 and married him on February 10 of the following year. At first she was determined that he should play no part in the government of the country (although a constitutional monarchy, royal influence in politics was considerably greater during the nineteenth century than it is today) but gradually relented. Within six months, Albert had access to the parliamentary dispatches. During Victoria’s first pregnancy, he was given his own key to the boxes containing information on affairs of State usually reserved for the eyes of the reigning monarch.

Despite the image that has come down through the years, Victoria was far from puritanical—especially in her younger days. Albert, on the other hand, was described by the Duke of Wellington as “extremely straight-laced and a great stickler for morality.” He had a strong, dominant personality and the influence of his attitudes on Victoria, though gradual, was profound. It is not overstating the case to say that he embarked on a training program for the queen. He taught her the virtues of hard work and orderly business methods, he taught her to insist on a say in ministerial appointments, and he taught her decorum. From his original position, which seems to have been almost that of a plaything, he became a towering power behind the throne—so much so, in fact, that historians refer to the period as the “Albertine Monarchy.” Victoria adored him, asked his advice, and frequently followed it, on almost every important decision. Then, when the habits had been firmly established over a period of twenty-one years, it all ended. Albert contracted typhoid fever and died after a brief illness on December 13, 1861. Victoria’s greatest influence was gone. She had no one to turn to. In the shock of her bereavement, she plunged into the horrors of a nervous breakdown that lasted two years.

Victoria withdrew during that time, temporarily relaxing her grip on the machinery of British politics, but even when she emerged from the worst of her emotional illness, she was unable to accept the change that had taken place. Instead of learning to stand on her own feet, to use her undoubted powers of judgment, she continued to behave as if Albert were still alive. When decisions had to be taken, she attempted to guess what Albert would have done and used this as her yardstick. At least such was the situation as seen by orthodox historians, but there may well have been more to it than that. Shortly after Albert’s death, a thirteen-year-old medium, Robert James Lees, held a séance in Birmingham during which, it was claimed, the spirit of the prince consort came through with the message that he wished to speak with his wife, the queen. The development received a measure of publicity—one of the sitters was a professional editor. His published account of the séance was subsequently brought to Victoria’s attention.

Despite her earlier interest in Spiritualism, the queen was by no means credulous. She was aware how often spurious communications followed the death of a public figure. Besides, her position dictated a discreet, low-key approach. She instructed two courtiers to attend the next Lees séance but warned them they were not to use their own names nor reveal their standing as emissaries from the court. If the courtiers were concerned, but not themselves believers in life after death, the séance must have come as something of a shock. The voice phenomenon produced by Lees was instantly recognizable as that of the late consort. More surprising still, the spirit addressed the courtiers by their real names. Eventually, reluctantly, they were forced to admit they had been sent by the queen.

It seems there followed a great deal of evidential material, including intimate details of life at the palace that only Albert could have known. The courtiers were impressed. But before the queen could take action, she received a letter from the schoolboy Lees. This letter was an example of automatic writing. According to Spiritualist theory, the shade of the deceased takes over the body—or at least the hand—of the medium long enough to pen a message. The message in this case was signed by a pet name used only between Albert and his wife and was packed with personal details. Victoria was utterly convinced that it represented a genuine spirit communication. She sent at once for Lees and a séance was held in the palace. The voice of Albert came through the medium and spoke to his delighted widow. Lees paid nine visits in all to Buckingham Palace and his séances impressed the queen so much that she asked him to join the royal household as resident medium. Lees refused the offer, apparently on the advice of his spirit guides, but did not leave the queen without solace. Albert’s final message through him assured her that another medium had been chosen to keep the line of communication intact. This medium was “the boy who used to carry my (Albert’s) gun at Balmoral.”

Albert had always disliked cities, especially London. Since Victoria’s first railway journey in 1842, the couple made a point of getting away from the capital whenever possible. After three visits to Scotland, which they both adored, a lease was taken out on Balmoral House near Ballater. In 1852, the estate was purchased outright and four years later, Balmoral Castle was completed. Victoria had always loved Scotland and a few periods of residence at Balmoral taught her to love the Scots as well. She and her consort lived in the Highlands “with the greatest simplicity and ease,” as Lord Grenville wrote. Albert went shooting. The boy who carried his gun was John Brown.

After Lees’s revelations, Brown was sent for and subsequently took up residence in Balmoral. He remained there, as Victoria’s constant companion and medium, for more than thirty years. It seemed that when she wished to find out how Albert would have viewed a particular issue, she did not, as historians suppose, have to use her imagination. Brown would mount a séance and the dead prince would speak for himself. Victoria kept a detailed record of these séances and after Brown’s death wrote a monograph about him that she wanted to publish. But her proposals were thwarted by her private secretary, Sir Henry Ponsonby, and by the then dean of Windsor, Dr. Randal Davidson, who was so disturbed by the prospect that he threatened to resign as court chaplain. Rather than risk scandal, Victoria abandoned the idea. Ponsonby got hold of Brown’s private dairies and destroyed them. But the massive cover-up operation was not as thorough as it might have been. Years later, George VI happened on a detailed record of a John Brown séance that had somehow managed to survive. He read it with great interest and mentioned the fact to his speech therapist, Lionel Logue. Eventually the story leaked out until it was made public by the popular British journalist, Hannen Swaffer, who was also a Spiritualist. Despite Swaffer’s revelations, Queen Victoria’s interest in spirit contact failed to make much impression on the public mind, and less still on the minds of those historians and biographers dealing with the Victorian period. Thus background material on the whole fascinating story is difficult to come by.

Victoria’s Spiritualistic interests reach down to the present day to produce a curious addendum to the tale. The most recent dramatic portrayal of the relationship between the queen and her servant is the movie Mrs. Brown starring Billy Connolly and Judy Dench. It contains no hint at all of the Spiritualist connection. But earlier, in 1975, Britain’s Independent Television screened a dramatized documentary series based on the life of Edward VII. The actor who played Brown in the series was William Dysart, a man with enormous interest in psychical research and mediumship. In May 1973, a friend of Dysart’s attended a séance held by the British direct voice medium Leslie Flint and there recorded a voice that claimed to be that of Brown. When Dysart heard the recording, he was intrigued enough to make his own copy. Some months later, when offered the part of Brown in the television series, he used the recording as a basis for his interpretation of the character and carefully copied the voice during his screen appearances.

But the importance of people like Brown, Lees, and Eagle far outstrips their entertainment value. The political life of France, Russia, and now Britain seems, within the last century or so, to have been profoundly influenced by spirit voices. Nor does the story end there.

Seventeen years after the death of Queen Victoria, the Armistice document ending the greatest military conflict the world had ever seen was signed in a railway carriage at Rethondes in France on November 11, 1918. Just two days earlier, the German emperor, Kaiser Wilhelm II, had been persuaded to seek asylum in the Netherlands, saving himself from capture and possible execution but assuring the collapse of the monarchy in Germany.

Wilhelm took up residence at Doorn, swiftly faded from the international limelight, and slipped with apparent ease into the lifestyle of a country gentleman. He died on June 4, 1941, his passing somewhat obscured by more important news. His native Germany was once again at war—and doing rather well, it seemed—under the guidance of a new leader. It was a curiously anticlimactic ending to the career of a man who was then universally held to have been personally, and almost solely, responsible for the eruption of World War I.

Today, however, historians increasingly tend toward the opinion that Wilhelm was an accomplice to war rather than its instigator. The kaiser himself may have shared this opinion if the description of his exile penned by Lewis Spence is to be believed. Writing just before the kaiser’s death, Spence claimed Wilhelm was “known to spend the greater part of his time in the privacy of his princely library.” But not, as one might suppose, studying politics, history, or military affairs. Spence claims the library was entirely comprised of books on the occult. Many of these works were on Freemasonry (a fringe aspect of the occult in most of its modern manifestations), but there was also volume after volume of works on less appetizing and more arcane societies like the Illuminati and the Cult of Lucifer.

The retired kaiser was, in Spence’s view, perplexed:

In advanced old age, the ex-Emperor of Germany seeks tirelessly in the pages of mystical books for those clues and traces which may guide him to a more precise understanding of the forces which not only seduced him into war, but, by reason of their own inherent defects and furious irrationalities, betrayed him into defeat and exile. Every work published which might seem to aid him in his quest is studiously scanned in the hope that it will cast some light, however vague, upon the identity of those hidden leaders of a secret and occult junta, who, he is convinced, were responsible for the calamity of 1914 and the debacle of 1918.3

The quotation is taken from a rare little work, now out of print, entitled The Occult Causes of the Present War—the “present war” being the 1939–45 conflict. Despite its florid style and a scarcity of evidence to back up its central thesis, Spence’s intuitions are worthy of respect. For the kaiser was indeed involved in the occult during his days of power, and there is no reason to suppose he abandoned his interest after his abdication.

Wilhelm was born on January 27, 1859, in Potsdam, to Victoria (the eldest daughter of the British queen Victoria) and the crown prince Frederick, who later became Germany’s Emperor Frederick III. The child had a withered left arm, and even in adulthood the limb never grew to full size—a fact often quoted in psychological analyses of his behavior. The boy grew into a man of stressed, restless, irresolute character, with a sense of duty, inculcated by a Calvinist tutor, that was often locked in conflict with his natural inclinations. In 1881 he married Princess Augusta Victoria of Schleswig-Holstein, who subsequently presented him with six sons and a daughter. Emperor Wilhelm I, the kaiser’s grandfather, died in 1888. Frederick came to the throne, but was dying of cancer. Wilhelm became kaiser at the age of twenty-nine.

It was quickly apparent that the new emperor did not see eye to eye with his chancellor, Otto von Bismarck. Bismarck had, of course, been largely responsible for the policies that created the German Empire in the first place, but he was aging. Wilhelm may have felt he was losing his grip. In any case, the kaiser drove Bismarck into resigning as chancellor in the early months of 1890. His successor, Leo Graf von Caprivi, tried unsuccessfully to find a policy that would be at once acceptable to the Reichstag and the aristocracy, personified in Wilhelm. Prince Chlodwig von Hohenlohe-Schillingsfurst, next in line for the job, was equally unsuccessful. By 1900, the former foreign secretary, Bernard Furst von Bulow, had become chancellor. He was very much the kaiser’s man and produced little of any real importance in solving Germany’s internal problems (which sprang largely from the country’s rapid industrialization). But he did abet the kaiser in a policy well tried by many other leaders faced with problems on the home front—the diversion of public attention toward more exciting matters abroad.

Wilhelm’s performance in foreign policy was tactless and blundering. He developed a habit of interfering in international disputes that had little bearing on the welfare of the German nation. In 1911, this almost led to war by way of the Agadir Crisis. In 1914, he finally pushed things over the edge.

During the first world conflict, Kaiser Wilhelm was supreme commander of the Armed Forces, and though he seems to have left most of the work to his generals, he did nothing to discourage their grandiose plans, which ruled out any chance of a compromise peace. Today, historians speculate on his motivation and occasionally supply psychological answers like compensation activity for his withered arm, or the acting out of inner conflicts occasioned by a dominant mother and passive father. Doubtless all these factors played some part in the international drama that cost so many lives. But historians who do not, by and large, believe in demons, tend to underrate the influence exercised on the kaiser by a man who for years had felt himself a channel for demonic forces.

Houston Stewart Chamberlain, as one might guess from his name, was not a German. His father was a British admiral, but he was brought up by relatives and educated in France and Geneva, with the result that French became his first language. At the age of fifteen, a Prussian named Otto Kuntze was appointed his tutor and promptly set about filling the boy’s head with the glories of the German race. In his twenties, Chamberlain, having already proven himself a brilliant pupil, was studying more edifying subjects like philosophy, natural history, medicine, physics, and chemistry. But the instilled love of things Germanic proved overpowering and he left Geneva at the age of twenty-seven for Bayreuth, where he was fortunate enough to meet the great German composer Richard Wagner, whose daughter he eventually married. In 1885 he moved with his first wife to Dresden, where his personal process of Germanization was completed. From 1889 he dwelt in Vienna, and in 1909 he returned to Bayreuth, where he lived until his death in 1927. His marriage to Wagner’s daughter Eva took place in 1908, following the divorce of his first wife three years earlier.

On April 1, 1897, Chamberlain began work on a book entitled Gundlagen des Neunzehnten Jahrhunderts (Foundations of the Nineteenth Century). By October 31, 1898, the massive manuscript was finished. When it was published the following year, it ran to some twelve hundred pages. Despite this formidable length, it went through no less than eight editions in the next decade. Chamberlain found himself famous in his adopted Germany. He was still famous in the Hitler era, long after his death. By 1938, his magnum opus had sold more than a quarter million copies.

Foundations of the Nineteenth Century is a book that purports to hold the key to history, and the key is an understanding of race. Any grasp of contemporary events, Chamberlain argued, could only be obtained by studying the historical legacy that influenced them. He saw this legacy as Roman law, the personality of Christ, and Greek philosophy and art. He maintained that the peoples who carried this legacy were the Jews, the Germans, and the Mediterranean Latins. But only the first two were pure races and only the Germans were worthy of their heritage. In Chamberlain’s eyes, it was the Teuton who saved humanity from the dark night of the Middle Ages and it was the Teuton who was the only real hope of the contemporary world. But he used the term broadly, taking in both Celts and Slavs and even those, of any race, who were philosophically Teutonic in their outlook. Nonetheless, he felt the importance of each nation was directly dependent on the proportion of Teutonic blood in its population. Chamberlain took some pains to insist he was not anti-Semitic and condemned this commonplace German attitude as “stupid and revolting.” But he took even more pains to insist that Christ was not a Jew, arguing that his Galilean origins and his inability to pronounce Aramaic correctly were at least indicative of a high proportion of non-Semitic blood if not a full Aryan pedigree.4

Chamberlain’s book also drew up a racial history of Judaism, tracing the mixture of Semite, Hittite, and Amorite blood. It was this final interbreeding that brought the Aryan strain into the bloodline. According to Chamberlain, the Amorites were “tall, blond and magnificent” but their racial intermingling came too late to do much good. The Jews were a bastard race—Chamberlain uses the curious word negative in this connection—lamentably lacking in true religion. In sharp contrast to this sorry picture was his portrait of the Germans, who had inherited the best qualities of the Greeks and Indo-Aryans and who were the foundation stone of God’s plan for the future of the world.

Among Chamberlain’s most avid readers was the leader of the German nation, Kaiser Wilhelm. The American historian William Shirer says it sent him into ecstasies.5 An invitation to visit the palace was dispatched and the two became firm friends. That there was a mystical element to the friendship is beyond question. Much of their subsequent correspondence has survived, filled with phrases like, “It was God who sent your book to the German people and you personally to me” and “Your Majesty and your subjects have been born in a holy shrine.”

As the friendship deepened, Chamberlain continually fed the kaiser’s visions of glory, encouraging him to take an increasingly extreme stance, particularly in matters of foreign policy. The kaiser, after all, was the living embodiment of a race destined to become masters of the world. This cause, to Chamberlain, was “holy,” as he reminded Wilhelm at the outbreak of the First World War. Germany, he said, would conquer the world “by inner superiority.” It appears on the face of it to be little more than the rantings of a racialist crank, but it is a curious fact that Chamberlain did not believe himself to be the author of Foundations of the Nineteenth Century. He felt it was written through him by a demon. Nor was the conclusion metaphorical. He saw the process as identical to that whereby Spiritualist mediums produce messages from the Beyond by permitting their bodies to be taken over by incorporeal entities.

Chamberlain was aware of demons for most of his life. They drove him relentlessly to study and write. Their promptings explained the butterfly approach to his student career as he hopped from music to philosophy to botany to history. In 1896, a demon assailed him while he was traveling on a train, so that he was forced to cut his journey short, shut himself up for eight days in a hotel room in Gardone, and produce a thesis on biology. Most of his major works were written in this way. He would fall into trance and work feverishly, with little attention to his own comfort or surroundings. Afterward he would read the material with a sensation of surprise, unable to recognize it as his own. Foundations was written like this, the result of a demonic possession that lasted nineteen months.

If this was a work of fiction and our natural disbelief in demons had been suspended, we might by now be waiting with some impatience for the hero of our story, who would surely be a mystic representative of the Powers of Light. In reality, such a figure did indeed appear in the form of the quartermaster general, Helmuth von Moltke, chief of the Imperial General Staff of the German Army.

Von Moltke was a student of medieval mysticism, with particular reference to the history of the Holy Grail. He was also a close personal friend of Rudolph Steiner, an occultist of genius, who taught that individual evolution could be hastened by means of esoteric exercises and techniques. Whether von Moltke actually practiced these mystic disciplines we do not know, for like most occultists he was more reticent about the application of his studies than about the studies themselves. But it is likely that he did; and it is known that his insights were deep enough to leave him profoundly disturbed by the influence of Chamberlain on his kaiser.

As Europe moved inexorably into war, von Moltke, in his capacity of chief of staff, supervised the complex mobilization of the German forces. He was at his desk in the Konigsplatz Headquarters when he was swept away by one of the most dramatic esoteric experiences of his career. He plunged into a spontaneous nine-minute trance, which army doctors afterward dismissed as the result of strain and exhaustion. Von Moltke interpreted the experience differently and bequeathed to future generations the description of an intriguing and impressive vision.

![]()

It seemed as if his mind was swept back through time to the ninth century, where he found himself observing incidents in the life of the medieval pontiff, Pope Nicholas I. Interwoven with this scene was a curious understanding of the historical process and a recognition that the world of centuries past had not obeyed the same hard rules of physics as governed our planet in 1914. In the days of Pope Nicholas, it was apparent that mankind was blessed with an expanded awareness, an extended conscious experience of spiritual realms and transcendental realities.6 But it was also apparent that such a state of consciousness would not last. In order that men should develop an analytical intellect and the scientific method take its proper place in the evolution of our species, a narrowing of attention became necessary. Pope Nicholas himself foresaw this development and privately predicted a time when the people of Europe would have only an awareness of three-dimensional reality. Direct experience of the spirit worlds would become the prerogative of a very few. For the masses, the only sustenance would be revealed religion; but even here, the activities of the Infernal Hierarchies would go a long way toward convincing men that the physical world was the only reality. Although the time scale of this grim development was measured in centuries, it was seen ultimately as a temporary necessity. The day would come when evolution reopened the psychic centers of mankind and once again allowed direct perception of spirit worlds.

In the course of his vision, von Moltke perceived something even more intriguing. He became aware of the effect of reincarnation on the historical process. It seemed to him that certain personalities reappeared on Earth at certain times, often grouped together to act out parallel dramas at different historical periods. In Pope Nicholas he recognized an early incarnation of himself, while his cardinals and bishops included members of the German General Staff. Later, in waking consciousness, all this struck him as unlikely, but the concept proved too disturbing to dismiss. Years of careful analysis showed him there were indeed parallels between the two situations. For example, both the medieval popes and the German General Staff were withdrawn from the mundane world, and, more important, both were vitally concerned with the future of Europe.

Perhaps the most disturbing aspect of the vision was the graphic prediction of mankind’s impending plunge into materialism. It was as if humanity were gradually falling asleep. Spiritual origins were forgotten. The once-empirical reality of higher planes and dimensions became nebulous and was eventually denied altogether. Blind chance was evoked to explain both the historical and evolutionary processes. In the forthcoming First World War, whole nations of sleepwalkers prepared to slaughter one another. This development was, perhaps, a spiritual necessity, designed to reawaken mankind through the medium of suffering, but it was an unpalatable necessity just the same. Von Moltke emerged from his vision a very troubled man.

The experience must have had a profound effect on von Moltke’s outlook. Yet despite the revelation that a long, hard war was necessary, history shows he did his utmost to shorten the duration of the conflict. But his efforts were fruitless in the face of circumstance. The German master plan failed miserably and swiftly, and the war settled into the horrific stalemate typified by Flanders Fields. The failure led to the dismissal of von Moltke and his replacement as chief of staff by General Eric von Falkenhayne. By 1916, von Moltke was dead.

His story did not, however, end with his death. His widow, Eliza, was convinced she could still communicate with him and brought through a lengthy series of messages that, some occultists maintain, still circulate in photocopies through several of Germany’s many modern secret societies. The messages were in the nature of prophecies: a defeat for Germany in the 1914–18 war, the fall of the Romanovs and the establishment of a Communist regime in Russia, the rise of fascism as an international creed, and the establishment of Adolf Hitler (whom he named) as the führer of Germany. There was, too, a reference to a familiar figure in these communications. Von Moltke predicted that his occult archenemy, Houston Stewart Chamberlain, would be among the first influential figures in Germany to welcome Hitler as the new messiah. In this, as in his other predictions, the spirit of von Moltke was all too accurate. None of these predictions was made in a vacuum. They were presented as essential outcomes of an unorthodox view of history, the long-term results of processes that began centuries earlier, hastened by the multiple reincarnations of personalities who had been intimately involved in the earlier dramas. They resulted from the communications of a disembodied spirit.

Within two decades, the disembodied spirits were at their war work again.