![]()

Julian Jaynes believed he could provide a convincing theory of spirits. As noted earlier, his researches led him to the conclusion that prior to about 1250 BCE, spirit contact with mankind was almost universal. But there came a point in human evolution when things began to change. The gods, for reasons that must have been incomprehensible at the time, began gradually to withdraw. Fewer and fewer of them walked visibly among humanity. They took to communicating from a distance so that only the divine voice could be heard. But even this voice faded with time. Jaynes charted these changes over an approximate thousand-year period by examining what happened to mankind’s oracles.

The first oracles, he believed, were no more than specific locations where anyone could go to listen to the voice of their gods. The surroundings might be impressive, perhaps a little frightening, and natural sounds like running water or whispering winds would be conducive to hearing voices. But there was no priest, no sibyl. If the gods declined to be present in the home, oracles were areas of holy ground where the deity might be persuaded to speak more freely.

But as time went on, the nature of these sacred places underwent a subtle change. Increasingly, the voices declined to converse with just anybody. Their words were reserved for priests or priestesses who attended at the locale. It was not that the spirits were reticent about giving advice—far from it. But their voices could only be heard by an elite who conveyed the gods’ instructions to the general public.

With the passage of the years, even the priests and priestesses could no longer hear the spirits unless they underwent a prolonged period of training and embarked on special ceremonies to persuade the discarnate entities to speak. At this point, however, the priesthood still listened to the gods and passed on their words.

Somewhere around the fifth century BCE, Jaynes believed, the situation changed again. The priests and priestesses could no longer simply listen. They had to allow themselves to be possessed by the spirit in order for communication to take place. This involved even more elaborate training and was hard on the medium, who would often foam and convulse under the strain. The process did, however, have the benefit of allowing people once again to hear the words of the god directly, albeit spoken through the mouth of a human host.

Unfortunately this benefit eventually disappeared as the words of the god became more and more garbled so that the utterings of a possessed medium had to be interpreted by a skilled expert and experienced in the process. This marked the split between priest and prophet, priestess and sibyl. In essence, some people trained as mediums and entered on careers as convulsive ecstatics while others became interpreters of the divine word. With the split came a shift in the power structure, giving the (interpretative) priest a special authority still claimed to the present day.

Jaynes believed the final step in this six-stage process came when the abilities of the sibyl grew so erratic that interpretation became impossible. At this point, the ancient oracles died out altogether. Delphi survived longer than most, but only, in Jaynes’s view, because of a cultural nostalgia for the good old days when the gods walked and talked with men.

But who or what were these “gods” who were responsible for the establishment of our earliest civilizations? The descriptions that have come down to us make it quite clear they were not the high moral and spiritual beings associated with our modern ideas of divinity. As many scholars have pointed out, the antics of the Olympians were a catalog of lust, greed, envy, and aggression— characteristics depressingly comparable to the worst traits of humanity.

Even more striking from our present-day viewpoint is that they were described as beings who walked and talked with humanity like physical kings. This has led to conjecture among less orthodox students of ancient history that the gods might not have been gods at all, but visiting aliens from some distant planet whose advanced technology was mistaken for magic and miracles. Jaynes too believed the gods were not real gods, but he has no time for the extraterrestrial hypothesis. Instead, he stated bluntly:

The gods are what we now call hallucinations. Usually they are only seen and heard by the particular heroes they are speaking to. Sometimes they come in mists … suggesting visual auras preceding them. But at other times they simply occur. Usually they come as themselves, commonly as mere voices, but sometimes as other people closely related to the hero.1

The idea that spirit voices were hallucinations is intimately associated in Jaynes’s thesis with another premise. Jaynes was convinced that human consciousness is a relatively recent acquisition. It is, he believed, an evolutionary development not much more than three thousand years old.

On the face of it, this seems unlikely. The earliest known civilization—the Sumerian—dates back to around 4500 BCE. Dynastic Egypt was established around 2925 BCE. The middle of the third millennium BCE saw flourishing metal-using cultures in Crete, the Cycladic islands, and the southern part of the Aegean mainland. Even the relatively recent civilizations of South America, generally dated no earlier than 1500 BCE, still arose at a time when, according to Jaynes, no human on the planet was capable of conscious thought. But Jaynes, a professor of psychology, argues that consciousness is not necessary even for the most complex of tasks. Although consciousness often plays a part in such activities as perception, judgment, thinking, reasoning, learning, and the assimilation of experience, it is not actually necessary for any of them.

If, for example, you close your left eye and focus with your right on the left-hand, left page margin of this book, you will still be fully conscious of the sweep of type across the two open pages. But if you then place your index finger at the start of any line and move it slowly right across the open pages, you will discover that there is an area in which the fingertip vanishes, only to reappear again a little farther on. This conjuring trick is related to the physical structure of the human eye, which has a blind spot in its field of vision. Since we dislike blind spots, we fill it in where it occurs, through a process analogous to a computer filling in a missing part of a picture by deduction from the rest. Once “filled in,” the former blank spot becomes part of your perception. Nor is it illusionary. While the perception does not come about through the usual process of light striking the retina, it is still a valid analogy of what is there on the printed page. Sweep your eye across and you will be able to read it, without having to worry about any blank. But while valid, this is a perception in which consciousness plays no part at all. You do not, in other words, notice the blank spot and think to yourself that it is something you must fill in. The process is entirely unconscious. So consciousness is not always necessary for perception.

The notion that judgment is a conscious function was demolished by the psychologist Karl Marbe as long ago as 1901, using a simple experiment. Marbe had an assistant hand him two small objects, and handed back the lighter of the two after carefully examining how he made the judgment. He realized he was aware of a great many things about the two objects: their feel against his skin, the downward pressure on his hands as they reacted to gravity, any irregularities in their shape, and so on. But when it came to making the judgment, he found that the answer was simply there, apparently inherent in the objects themselves. Actually, the judgment was made by the central nervous system at a wholly unconscious level.

It was an attempt by another scientist, H. J. Watt, to punch holes in Marbe’s experiment that led to the truly astonishing discovery that thinking, apparently the most obviously conscious of all human activities, is not a conscious process either. Watt suspected that the whole business of weight judgment was not actually unconscious but a conscious decision that happened so quickly that Marbe’s subjects simply forgot what they had done.

To try to prove this theory, he set up a series of word-association experiments that allowed the process to be broken down and examined in four constituent parts. The results of these experiments showed that, provided the subject understood in advance what was required, thinking became entirely automatic. It arose, of its own accord, once the stimulus word was given. As Jaynes says, one thinks before knowing what they’re supposed to think about. In other words, thoughts are not conscious. Consequently, in this instance, as in many others, consciousness is not necessary for one to think.

It is apparently unnecessary for reasoning also. The celebrated French mathematician Jules-Henri Poincaré told the Société de Psychologie of Paris how, on a trip, he had solved one of his most difficult problems:

The incidents of the journey made me forget my mathematical work. Having reached Coutances, we entered an omnibus … At the moment when I put my foot on the step, the idea came to me, without anything in my former thoughts seeming to have paved the way for it, that the transformation I had used to define the Fuchsian functions were identical with those of non-Euclidian geometry.2

The process by which Poincaré reached this conclusion did not require consciousness. Nor did the processes by which the structures of the atom and the benzene molecule were discovered or the solution to the mechanical problem of how to construct a viable sewing machine. In all three instances the solutions came through dreams.

Learning does not require consciousness either. Indeed, in some types of learning, the intrusion of consciousness actually blocks the process. This is particularly true of what is called “signal learning,” sometimes referred to as conditioning or, less pejoratively, learning by experience. When a puff of air is blown into someone’s eye, they blink—the reflex is involuntary. If a light is shone into the eye immediately before blowing and the process is repeated several times, the eye begins to blink at the light, before the puff of air. The subject’s body has learned that the stimulus is about to come and anticipates it by blinking. But there is no consciousness involved in this learning process. So far as the subject is concerned, it simply happens. Furthermore, if the subjects tries to speed up the process by blinking consciously after every flash of the light, the reflex will arise much more slowly, if at all.

A great deal more than reflex actions can be learned without the intervention of consciousness. A charming case study reported by Lambert Gardiner in Psychology: A Study of a Search tells of a psychology class that decided to teach their professor that they preferred him to stand at the right of the lecture hall. Each time he moved to the right, they paid closer attention to what he was saying and laughed more heartily at his jokes. While he remained completely unconscious of what was going on, he was soon delivering his lectures so far to the right of the hall that he was almost out the door.

Assimilation of experience is often associated with consciousness—indeed there was a time when psychologists defined consciousness as the assimilation of experience. That time has long gone. It is fairly likely that you use a telephone frequently and apply the full light of consciousness to the various numbers you dial. But could you say now, without looking, what letters are associated with what figures on the dial? You brush your teeth each morning: how many are on view in the bathroom mirror as you do so? Could you list, again without looking, the ornaments on your mantelpiece? A few attempts like these quickly indicate how poor a vehicle consciousness is in assimilating your daily experiences.

Most people will notice instantly when a familiar clock stops, even though the sound if its tick may not have impinged on their consciousness for years. Not hearing the clock tick until it stops is a familiar cliché, but one that demonstrates clearly that assimilation of experience (the clock stopping) can be carried out very efficiently without consciousness. This is even more clearly demonstrated by the use of hypnosis in situations like the loss of car keys. In a trance, people can often be persuaded to recall where they left them, even though consciously they have no awareness of their location whatsoever. The experience of leaving the keys was not consciously recorded, but it was accurately recorded all the same.

It is now clear that consciousness is unnecessary to survive even the busiest day. Indeed, it is observable that consciousness is not only unnecessary in daily life, but also unexpectedly absent from much of it. When driving a car, for example, the driver is no longer aware of the various complexities involved. He or she does not think consciously of applying the brake, changing the gear, or moving the wheel so many inches clockwise. These things, so far as consciousness is concerned, simply happen—although consciousness can override any one or all of them at will. The same applies to activities like riding a bicycle, skiing, using a typewriter, or operating machinery, however complex, with which one is really familiar. It is as if, during waking hours, we are accompanied by an invisible robot to whom we can hand over control of those functions with which we do not personally wish to be bothered.

There is strong survival pressure toward handing over as much as possible to the robot, since it can often do the job a great deal better than the individual concerned. Anyone may cast their mind back to the time when they were learning to drive a car. Every operation had to be carried out consciously, at a substantial investment of memory and attention. One had to remember to depress the clutch before engaging a gear. One had to estimate (or read off a dial) the precise engine revs that would allow this to be done comfortably. One had to judge distances and the width of the vehicle accurately and continuously. The whole process was a nightmare; and while it remained conscious, one drove badly and with difficulty.

The same process is evident in a baby learning how to walk. It is a pitiful process, full of stumbling and heavy falls. But every adult was like that once, a bipedal animal who could crawl but not walk. With instinct and encouragement we learned, but learning—in this, as in so many things—meant turning over control to the robot. When it came to walking, we manage this so effectively that, unlike car driving, consciousness no longer has a veto over how it is done. The curious fact is that adults no longer have the least idea how to walk. They decide where you want to go, of course, and when, but the process that establishes their balance, contracts their muscles, and initiates subtle, continuous feedback controls is as far beyond reach as the surface of the moon.

Clearly, if there are things like driving a car that the robot can do better, there are also things like walking that the robot can do perfectly and the individual cannot do at all. This fact encourages us to hand over more and more tasks to robot control. Sometimes this is done quite consciously. Zen Buddhism, when applied to tasks like archery, is a case in point. The Zen practitioner is encouraged not to aim at the target but to “become one with it” and allow the target to “attract the arrow.”3 This is really a process of giving the bow to the robot, which shoots a great deal more accurately than the archer. More modern sports systems, such as Inner Tennis—which allows players to rehearse their technique imaginally before putting it into physical practice—aim at substantially the same result. Athletes everywhere readily accept that they reach their peak when they cease to think—and worry—about their game.

So long as we are discussing motor skills, this situation is acceptable. Indeed, it is absolutely necessary. But the trouble arises when the robot starts to do the thinking. Robotic thinking is by no means uncommon. Crass examples abound in the oratory of politics and religion, where enthusiastic practitioners chant slogans at one another, under the comfortable impression that they are engaging in a debate. They are, in fact, merely sitting on the sidelines of a robot war.

Other examples are more subtle, consequently more dangerous. How often have any of us found ourselves parroting an opinion that actually belonged to the newspaper read that morning? How often have words reflected a mindless reaction to some stimulus that effected individuals in ways they did not really begin to comprehend? How often has one passed the time of day with a neighbor, discussing the weather, or even the garden, with no more conscious input than pressing the playback button of a tape recorder? In all of these familiar situations, it is the robot that is actually speaking.

Sad to say, the robot is an eminently helpful creature, eager to take more and more of the burden from conscious shoulders. It will breathe, walk, drive, speak, even think for us, and, unless we are very, very careful, psychoanalysts claim, it will live our lives for us. But to Professor Jaynes, this slipping back into unconscious, robotic living is an evolutionary regression, a personal mirroring of the way things used to be for the whole of humanity. Prior to about 1000 BCE, everyone left their lives entirely to the robot and had no hope at all of waking up and taking charge. Consciousness as we know it simply did not exist.

In this curious psychological state, humanity moved from its primitive hunter-gatherer existence to develop agriculture, establish villages, then towns, and, eventually, city civilizations … all without a single conscious thought. But not without help. According to Jaynes:

Volition, planning, initiative (was) organised with no consciousness whatsoever and then “told” to the individual in his familiar language, sometimes with the visual aura of a familiar friend or authority figure or “god” or sometimes as a voice alone. The individual obeyed these hallucinated voices because he could not “see” what to do himself.4

This is an exciting concept and one that might go some way toward solving the dilemma of the voices heard by so many people across the sweep of history. But is there really evidence to underpin it?

Jaynes used the 1959 excavation of a Mesolithic site at Eynan, twelve miles north of the Sea of Galilee in Israel, as an important foundation of his conclusions. The remains discovered belonged to the Natufian culture (itself named for another Israeli site) but were like nothing ever seen before. The Natufians were hunter-gatherers who up to then were believed to have used flint weapons and lived in cave mouths. But the excavations unearthed evidence that changed the picture completely. What the archaeologists found was no nomadic site but a permanent town—the first of three to be discovered—of circular stone-built houses. Among the structures in this primeval community was what Jaynes believed to be the earliest known example of a king’s tomb. There are suspicions that this structure may have been constructed in stages, with each stage marking some form of religious development. Within the innermost, hence earliest, chamber were two skeletons. One was of a woman wearing a shell headdress. The other was of an adult male. Archaeologists looked to the elaborate nature of the tomb and decided the individuals buried inside must have been the world’s first king and his consort.

Jaynes himself went further. He argued this was not simply the world’s first king, but the world’s first god-king. To understand why he reached this conclusion, we must put it into the context of his theory that at the time the Natufian culture flourished, humanity did not possess consciousness.

What was such a state actually like? We have already examined how easily any one of us might slip back into robotic function, but today this is always a temporary condition. We wake up often enough to accept wakefulness as our natural state. Indeed for many of us it seems to be our only state since the bouts of robotic behavior tend to get forgotten. Furthermore, a robot take-over does not rob us of consciousness completely—only of a consciousness of the task the robot happens to be performing. The searchlight inside our head simply turns elsewhere, to think about a different problem, plan our day at the office, fantasize about a loved one. It does not switch off altogether. But when the robot took over completely, as Jaynes believed it did for most of human history, things were very different.

Jaynes claimed that these people lived with no sense of ego whatsoever, no Joycean “stream of consciousness” maintaining an inner dialogue. The unconscious state influenced their experience of memory. There was obviously no such thing as conscious recall, no decision to remember, no struggle for the word on the tip of the tongue. Function was always and forever a matter of stimulus-response. And when in a new situation they were instructed by a voice of authority.

This is one of the most interesting aspects of Jaynes’ theory. Today, “hearing things” or “seeing things” generally suggests the need of treatment in a mental hospital, but such symptoms are only indicative of insanity in acutely distressed people—and sometimes not even then. Although there has been very little formal research on the subject, one survey across a population base of more than 15,000 showed 7.8 percent reported hallucinations among healthy men and 12 percent among healthy women. Visual hallucinations were twice as common as auditory and the highest frequency was reported between the ages of 20 and 29. National differences emerged with Russians and Brazilians experiencing many more hallucinations than the overall average. In all cases, the people involved were physically and mentally healthy.

The discovery that it was possible to remove parts of the right brain without influencing the patient’s well-being led early psychiatrists to conclude that much of the right brain was simply unnecessary. Jaynes believed that the right brain mirror of Wernicke’s Area once functioned to organize experience—including interactions with authority figures like tribal chieftains —and code it into admonitory “voices.” These were then transferred across the corpus collosum to be picked up, hence “heard,” by the Wernicke’s Area in the left brain. In essence, the right brain “Wernicke” was an hallucination generator, but the hallucinations themselves were beneficial and survival oriented.

It is easy to understand the necessity for a coding mechanism that will allow the individual to benefit from experience. Without it, we could not possibly survive. But once we understand the nature of the two hemispheres, it is easy to see how this particular coding mechanism led to belief in the gods. From our present perspective, we can appreciate that the messages passed across the corpus collosum were an amalgamation of personal life experience and the instructions of one’s tribal or family superiors. But that, of course, is not how they were experienced. The transfer to the Wernicke Area ensured they were heard as spoken orders and mistaken for objective speech. The “voice” might occasionally be the voice of a relative, living or dead, sage, chief, king or other authority figure, but however presented it would always carry the additional numinousity of the right brain. Even today, right brain contact—in the form of inspiration, for example—will often elicit a feeling of awe. The poor, pedestrian left brain simply is not used to the creative fireworks. How much more striking must the sensation have been when the contact came in the form of hallucinatory orders. No wonder our ancestors concluded they were listening to a god. That conclusion was reached, Jaynes theorized, if not at Eynan in 9000 BCE, then at some time and place very close. But it is Eynan that provides us with the evidence. In the king’s tomb, the bones of the woman indicate that she was laid out more or less as you might expect, lying on her back to take her eternal rest. But the man was not. He was buried in a raised position, propped in place with stones.

On the face of things, it is difficult to see why any tribe should take the trouble to do this with the body of their dead king. But Jaynes thought he knew. While the king lived, his voice—the voice of immediate authority—was incorporated into the hallucinations of his followers. When he died, the voice remained. To the followers the conclusion was obvious. The king was not dead at all. They propped him up so he could continue to give them orders. And at some point, their intellectual evolution was sufficiently far advanced to allow them to draw an even more important conclusion. Since the hallucinated voice carried the numinousity associated with the right brain, it eventually dawned on the tribe that a dead king was a god-king.

From this primitive beginning, sprang virtually the whole religious edifice of human thought. Belief in postmortem survival, ancestral spirits, and the reality of a divinity or divinities, all rests on this hallucinatory foundation, itself firmly rooted in the very structure of our brains. Our ancestors had no need of faith. They knew these things from personal experience.

The physiological foundation of Jaynes’s theory is based partly on the discovery that the human brain is divided into two hemispheres, each with a specific function and a particular mode of mentation. In essence, there are two identities inside the skull. They normally cooperate seamlessly. The left hemisphere, in 95 percent of the population, is associated with logical thought, reasoning, speech and consciousness. The right hemisphere is the creative half of the partnership, providing such functions as intuition, aesthetic values, visions and dreams—the stuff of the unconscious. It is important to realize that the “entities” who “inhabit” both hemispheres are capable of thought and rational function, but the one that humans are most aware of and think of as their identity is personified in the left hemisphere.

In the left hemisphere, there are three areas related to the function of speech. The most important is Wernicke’s Area, a portion of the left temporal lobe above and to the rear of the left ear. It stores and processes vocabulary, syntax, meaning and understanding. Destroy it in an adult and he or she will be rendered incapable of meaningful speech. But if the entire portion of the right brain corresponding to Wernicke’s Area is removed—as has been done surgically to treat certain conditions—nothing much happens. The ability to speak and verbal thinking are unaffected.

This then was Jaynes’s explanation of what spirits are and where they come from. In simple summary, the whisperers are self-generated hallucinations and the spirit world is firmly located in the soft gray matter of the right brain. But rational though it sounds, it is an explanation that does not hold water.

Julian Jaynes first summarized his ideas on humanity’s emerging consciousness at an invited address to the American Psychological Association in Washington in 1969. His reception was sufficiently positive to encourage him to publish a much fuller account in 1976. Despite a sober, unmemorable title, The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind generated such widespread interest that it was issued in paperback. Critical reaction was, to say the least, generous. One reviewer suggested his theory might become the most influential idea presented in the second half of the Twentieth century. Another found his evidence “compelling.” A third compared him with Freud in his ability to generate a new view of human behavior. But impressive though it was, there are weaknesses in Jaynes’s case.

Although it was his reading of the Iliad that first made him wonder about the provenance of human consciousness, Jaynes chose to begin his historical evidence with the Mesolithic burial at Eynan. Here was his first mistake. During the 1960s, when Jaynes began to examine the evidence, the archaeological consensus of prehistory was based on the assumption that political structures and religious beliefs were more or less similar to those of historical times. Specifically, it was assumed that rulers, be they tribal chiefs or primitive kings, were male.

This assumption ran so deep that when archaeologists reported on their study of Minoan Crete, they referred constantly to a line of kings despite the fact that not one single representation of a male ruler was ever found. When the evidence for female involvement in political life became too strong to ignore, it was explained away by the suggestion that the women may have taken temporary charge while their men were at sea. Here too the conclusion was unsupported by any evidence. This sort of pervasive, if largely unconscious, chauvinism remains a feature of archaeology to this day. It is certainly a feature of Jaynes’s analysis of the Eynan burial.

In the tomb, the excavating archaeologists found two human skeletons, one male, one female. Given the elaborate nature of the structure, it was obvious these had been important personages. Jaynes assumed it was equally obvious that the male was the more important of the two. It was the male who was identified as a king and, since he had been buried in an unusual way, the foundation of the hallucinatory voice theory was neatly laid down. As king, he represented the ultimate authority figure in life. His bicameral (unconscious) subjects functioned on the instructions of their leader and when he died, the stress of the loss caused them to hallucinate his voice. In fact there is absolutely no evidence to suggest the male really was the more important of the two. Rather the reverse—it was the female who wore the headdress. The only significant thing about the male—and it seems of very small significance when stripped of Jaynes’s elaborate speculations—was that he was not buried lying flat. His head was propped on a pillow of stones while more stones were piled on top of his lower body.

Since Eynan was first excavated, substantial evidence has accumulated that our earliest ancestors believed, almost exclusively, in a female deity. At Çatal Hüyük, for example, James Mellaart discovered remains of Neolithic shrines dated to about 6500-5800 BCE. Huge figures of goddesses are modeled in high relief on the walls. A series of stone and terra-cotta statuettes found in these shrines represent a female figure, sometimes accompanied by leopards. The main deity of these Neolithic people was clearly a goddess, a mistress of animals. Her character was vividly depicted on a schist plaque carved to represent two scenes, a sacred marriage and a mother with child. At Hacilar, near Lake Burdur, a somewhat later culture revealed further statuettes of goddesses associated with felines.

The idea that our forefathers believed God to be female proved a bitter pill for archaeologists. They have typically fought a rearguard action from the position that female deities represented a local aberration, to the idea that there may once have been a goddess cult, and finally, with enormous reluctance, to their present position that prehistory was characterized by a near worldwide worship of the Great Goddess. Since political structures are an outgrowth of human thought and human thought is an outgrowth of human belief, it is likely that at a time of Goddess worship, temporal authority was mainly vested in women. This means that in the Eynan burial, the recumbent female with the shell headdress is far more likely to have been queen of her community than the male was to have been king. At best he may have been a consort with some associated prestige but probably little-enough real authority. He could equally well have been the woman’s son or the Natufian equivalent of a boy toy. In such circumstances, the propping of the head may be of no importance whatsoever.

But this is not the only weakness in Jaynes’s case. The psychological aspect of his overall thesis is based on the assumption that the breakdown of the bicameral mind was largely triggered by the invention of writing. At the time he developed his ideas, the orthodox consensus held that writing was invented in Sumaria sometime in the third millennium BCE. This tied in rather neatly with the remainder of his evidence, which appears to show a gradual shift in human mentation from that time until 1300 BCE when the bicameral breakdown became widespread and very evident. By 1979, however, there were indications that writing was actually invented far earlier than the orthodox consensus allowed. American academics Allan Forbes Jr. and T. R. Crowder found a hitherto unrecognized script incorporated in Upper Palaeolithic cave art. Nor was this unexpected discovery a series of crude glyphs. It carried all the indications of a developed alphabet. The implication is that the earliest writing must have predated the Upper Palaeolithic by a substantial margin.

These American findings were supported by an increasing volume of evidence from other fields. As long ago as 1956, another American academic, Professor Charles Hapgood, put his students to work on the analysis of several ancient maps that seemed to show some curious and anomalous features. Although he published the results of this work in 1966, they were not well received—or indeed widely discussed—by his fellow academics. Nor was this surprising. Hapgood concluded, against the rock-solid consensus of his day, that the maps contained evidence of an advanced civilization (unequaled in Europe before the second half of the eighteenth century) that had flourished in the Ice Age.

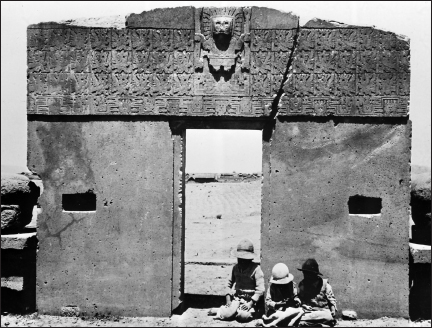

Bolivia’s Tiahuanaco ruins, believed by some to be more than 17,000 years old

Conventional wisdom has it that the last Ice Age ended about ten thousand years ago. To have flourished during this era, Hapgood’s lost civilization must logically have been established at a far earlier date. This too seems to be borne out by a wealth of supporting evidence.

High in the Bolivian Andes, for example, lie the cyclopean ruins of Tiahuanaco, an ancient city built using earthquake-proof architectural and engineering techniques we would find difficult to match today. Because of the sophistication of the buildings, archaeologists initially assumed Tiahuanaco had to be of recent origin and dated its foundation around 150 BCE with a growth pattern that ended as late as 900 CE. However, this dating has failed to withstand serious scrutiny. The problem is that an extensive area of Tiahuanaco—called the Kalasasaya—functioned as an astronomical observatory. Most modern archaeologists accept this without question, but one, Arthur Posnansky, decided to use the ancient observations recorded in the stonework to date the site itself. His initial figures indicated the city was functioning in 15,000 BCE.

Although his findings were accepted by the Bolivian government, Posnansky’s academic colleagues were not so sure. One of them, a German astronomer named Rolf Muller, pointed out that the figures could easily point to a date of 9300 BCE. Even this calculation indicates the existence of a sophisticated urban culture with advanced building techniques in the Ice Age, exactly as Hapgood predicted from his maps. But Muller himself decided that the evidence could be interpreted to support Posnansky’s earlier date. The only real reason for questioning it was that it seemed incredible.

Incredible or not, Posnansky’s 15,000 BCE dating of Tiahuanaco is actually superseded by a very curious dating of the ancient Egyptian civilization given by the Ptolemaic priest Manetho. Contrary to the beliefs of modern Egyptology, which dates the unification of Egypt and the foundation of dynastic rule to about 3100 BCE, Manetho maintained that prior to the pharaohs we know about, a line of predynastic monarchs ruled for a period not far short of fourteen thousand years. If the figure is correct, it would date Egyptian civilization to an era some two thousand years earlier than the “fantastic” date calculated by Posnansky for Tiahuanaco—once again in the depths of the Ice Age.

Since Hapgood’s lost civilization has not been precisely dated, it is worth noting that Manetho claimed the prehistoric rulers were preceded by a dynasty of “Horus-Kings” dating back a further 15,000 years. But even these extraordinary figures are conservative when compared to those given in a much older source, the Turin Papyrus. The papyrus, which appears to have been written around 1400 BCE, agrees with Manetho, more or less, by allocating a 13,400-year reign to the predynastic pharaohs. However, the Horus-Kings were said to have begun their reign some 23,000 years earlier, giving a foundation date for ancient Egypt in the region of 36,400 BCE. It perhaps goes without saying that while orthodox Egyptology is happy to accept both these sources as reliable guides to the kings of dynastic Egypt, the earlier figures are dismissed as fantasy.

In recent years, however, the orthodox view has come under increasingly violent attack. Critics have pointed to the long recognized—and long ignored—mystery surrounding the development of Egyptian culture. The archaeology of the Nile Valley does not indicate the expected stage-by-stage developments from primitive hunter-gatherers to sophisticated urban dwellers. Instead, the entire edifice—including the engineering skills that built the pyramids—seemed to spring up out of nowhere. Since this is manifestly impossible, the suggestion has been made that the civilization evolved elsewhere and migrated to the valley around 3100 BCE. If this suggestion is correct, it follows that the civilization itself is older—possibly far older—than the orthodox consensus allows.

Support for this view comes not from an Egyptologist but from a geologist. Professor Robert Schoch of Boston was asked to date the Great Sphinx at Giza on the basis of its weathering patterns, and he came up with a minimum figure of 5000 BCE. He thought there was a distinct possibility it could be anything up to two thousand years older. These dates may seem conservative when compared with those in the Turin Papyrus, but they are still thousands of years earlier than the orthodox consensus allows.

Although figures like the Sphinx and mysterious ruins like Tiahuanaco have gripped the public imagination, they represent only a small tip in an iceberg of evidence that now points to the existence of a far more sophisticated prehistoric culture than has generally been believed. This evidence is examined in considerable detail in two of my previous books.5

Copper was mined before flint in Serbia. There are prehistoric copper mines on Lake Superior and in California, Arkansas, New Mexico, Missouri, Illinois, Indiana, Georgia, New Jersey, and Ohio. Prehistoric iron-smelting furnaces have also been found. Manganese was mined near Broken Hill in Zambia 28,130 years ago.

In 1987, Birmingham University archaeologists Lawrence Barfield and Mike Hodder excavated a prehistoric sauna. Another was discovered in the Orkney Islands.

There is evidence that the horse was domesticated in Europe sometime before 15,000 BCE. A cave drawing at La Marche in France shows one wearing a bridle, as do prehistoric engravings found at the Grotte de Marsoulas and St. Michel d’Arudy.

Tumuli on New Caledonia and the Isle of Pines in the southwest Pacific contained more than four hundred man-made cement cylinders thirteen thousand years old. There are paved prehistoric roads in Yucatan, New Zealand, Kenya, and Malta. There is a water tank in Sri Lanka with a surface area equivalent to Lake Geneva. There are 170,000 miles of underground aqueducts, thousands of years old, in Iran.

Not alone does the evidence point to a high-level prehistoric civilization with substantial technical skills, but there are clear indications that our species has had a much longer history on the planet than orthodox science currently allows. In 1969, for example, twelve fossil footprints dated to 1,000,000 years BP were discovered between Woolongong and Gerringong, Australia. A year later, construction workers on a dam near Demirkopru, in Turkey, discovered a set of human footprints pressed into volcanic ash. They are 250,000 years old. In 1997, human artifacts 116,000 and 176,000 years old were found at the Jinmium site in Australia’s Northern Territories. Finds in Siberia, England, France, and Italy indicate human habitation of those countries prior to 1,000,000 BP, the time most orthodox scientists believe the first hominids (Homo erectus) were only just beginning to leave Africa. England, Belgium, India, Pakistan, and Italy are just a few of the countries that have yielded up weapons and other implements in strata older than the 2 million years commonly assigned to the evolution of Homo habilis, the first tool-user.

All this—and I would stress again that the foregoing finds represent only a very few examples selected from a vast body of evidence—would appear to put paid to the simplistic linear progression of human evolution on which Jaynes developed his theories. If you accept the orthodox picture of prehistory, it is easy to understand how he came to believe the primitive hunter-gatherer communities—assumed to represent the highest development of humanity prior to about 7000 BCE—were characterized by a bicameral mind. It is also easy to trace the threads of evidence that led him to conclude that the introduction of large-scale urban communities (about 5000 BCE) began to put pressure on the ancient bicameral structures while the development of writing led to their eventual breakdown.

Once you realize that the orthodox picture of this linear progression is in error, what appeared to be evidence supporting Jaynes’s theory quickly falls away. If urban civilization and the invention of writing were key factors in the development of consciousness, then consciousness developed not between 3000 and 1300 BCE but with the emergence of an advanced—and, according to Hapgood, global—civilization in the distant depths of the Ice Age.

But the new ideas about prehistory only throw into doubt Jaynes’s notions about the emergence of consciousness. They leave untouched his whole body of research into humanity’s widespread experience of voices and visions. This is distinctly weird, for it means that Jaynes’s examination of ancient history has unearthed something quite extraordinary. He has shown, from an analysis of inscriptions and texts, that there was a time within recorded history when virtually everyone could hear “spirit” voices and sometimes see “spirit” visions. He has also shown that the ability gradually atrophied—or, if you prefer, that the “spirits” gradually withdrew. His analysis suggests they disappeared altogether with the last of the great oracles. But we know this was not the case. Throughout human history, for good or ill, the voices have never ceased. In such circumstances, we may be justified in asking if the human race is mad, for our objections to Jaynes’s theory refer only to his postulate of the bicameral mind. They leave open the possibility of hallucinations stemming from some other source.