![]()

IN 1895, CARL GUSTAV JUNG, THEN AGED TWENTY, BEGAN HIS MEDICAL studies at the University of Basel, but events in his early life had already directed his attention to the possibility of a career in psychiatry, a somewhat disreputable profession at the time. Five years later, he was working in the Burghölzli, a psychiatric hospital in Zurich, and researching his doctoral dissertation, later published under the title On the Psychology and Pathology of So-Called Occult Phenomena. The object of his research was his fifteen-year-old cousin, Helene Preiswerk, who had begun to experiment with table-turning in July 1899 and only one month later was already showing signs of mediumistic somnambulism. Jung attended her séances almost from the beginning and made careful note of the phenomena she produced.

Helene’s first spirit contact was with Samuel Preiswerk, her grandfather, whom she had never known during his lifetime. Witnesses who had known him remarked on how accurately she conveyed his voice and manner. She was, it appears, what the Spiritualist movement calls a “direct voice medium”—that is to say, the spirits would take control of her vocal cords while she was in trance and speak directly to sitters through her. In this way, she “brought through” various deceased family members, several of whom spoke flawless High German, in stark contrast to Helene’s customary Basel dialect. The sittings were impressive, so much so that people began to come to her for advice, an unlikely development considering her age. Soon she began to exhibit a different kind of mediumship in which she remained aware of her surroundings but took on a new persona called Ivenes, a quiet, dignified, more mature character altogether.

In September 1899, someone presented her with a copy of Kerner’s The Seeress of Prevorst and her manifestations changed again. She took to magnetizing herself using mesmeric passes during her sessions and, possibly as a consequence, began to exhibit the ability to speak in a wholly unknown language.1 In her Ivenes persona she claimed to visit Mars, where she saw firsthand its great canals and the flying machines of its advanced civilization.2 She claimed interstellar journeys as well and visited spirit worlds to receive instruction from “clear spirits” while she herself gave instruction to “black spirits.” Jung noted that the spirits manifested in her tended toward two distinct types—the dour and the exuberant—corresponding with the mood swings of Helene’s own somewhat volatile personality.

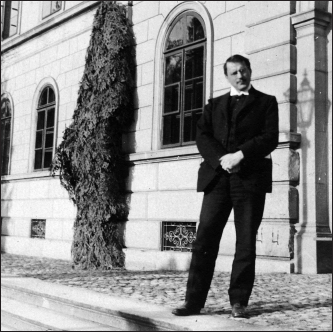

The young C. G. Jung, who earned his doctorate with a thesis on spirit mediumship

Helene meanwhile began to produce detailed memories of what purported to be past lives. She had been a Christian martyr at the time of Nero, a thirteenth-century French noblewoman named Madame de Valours who was burned as a witch, a young girl seduced by Goethe, and a host of others. In many of these incarnations she had borne children, who produced their own descendants, so that over a period of only a few weeks, she constructed an elaborate network of genealogies that often stretched down to her present day. Sometimes these became complex indeed. As the mother of Goethe’s love child, for example, she became Jung’s great-grandmother.3 As Madame de Valours, she was the mother of Jung in a previous incarnation. More complexities were to follow. By March 1900 she had begun to elaborate her own cosmology. Jung stopped attending her séances at about this time, but some six months later Helene was discovered engaging in fraud when she began to produce apports, small objects alleged to be mystically transported into the séance room by spirit helpers.

Jung interpreted the totality of the phenomena produced by Helene in the light of current German and French psychiatric theory, based on developments and experiments dating back more than a hundred years to the time when Franz Anton Mesmer believed he effected his cures through the medium of an invisible fluid. His star pupil, Amand-Marie-Jacques de Chastenet, Marquis de Puységur, came to think differently. By the summer of 1785, when a Strasbourg Masonic Lodge asked him to teach its members the principles of animal magnetism, he summed up the entire doctrine in two words: belief and want. “I believe that I have the power to set into action the vital principle of my fellow men; I want to make use of it; this is all my science and all my means.”4 He had come to see certain conditions and their cures in terms of psychological rather than physical processes. In so doing, although the fact is seldom acknowledged, he laid the foundation of modern psychiatric theory.

Puységur donated a practical technique as well. Mesmeric healing was based largely on the production of a series of crises in the patient, who would typically convulse violently for a time, then emerge improved in health and finally cured. While Puységur was attempting to induce a convulsive crisis in a twenty-three-year-old peasant named Victor Race, whom he was treating for a minor respiratory complaint, the patient exhibited a very peculiar reaction. Instead of convulsing, he fell into a strange kind of sleep in which he appeared to be aware of everything going on around him, was capable of answering questions, and actually seemed more alert and intelligent than in his normal waking state. When Mesmer was consulted about the development, he proved less than impressed and dismissed the new state as a “sleep crisis”—just one of various mesmeric crises, and not even a particularly important one. He proved wrong on all counts. The new state had nothing to do with sleep. It was not just one of various mesmeric crises; in fact, it was not a mesmeric crisis at all. And it ultimately proved more important than mesmerism itself. Puységur had inadvertently discovered the art of hypnosis. His experiments with the technique quickly convinced him that the real curative agent was not some mysterious magnetic fluid but the exercise of the magnetizer’s will.

It was not the only presage of things to come. Toward the end of his life, in the latter half of the nineteenth century, Justinus Kerner, the parapsychologist who investigated the famous Seeress of Prevorst, fell into a depression. To divert himself, he took to making inkblots on a sheet of paper, which he would then fold in half. He elaborated on the resultant shapes, referring to the final figures as klecksographien, which he said were ghosts and monsters, each assigned to its own place in Hades. His book on the subject, posthumously published and also called Klecksographien, became in later years the inspiration of Hermann Rorschach in his development of modern psychology’s inkblot test.

At much the same time, the French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot was making an international name for himself for his work in the Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris. His most spectacular achievements were the success of his efforts to have hypnotism accepted by the French Académie des Sciences and his investigation of traumatic paralysis,5 which he showed often to have psychological roots that lay outside the patient’s awareness. Hypnotism itself was investigated and the discovery of aspects like somnambulism and posthypnotic suggestion implied the existence of an area of the mind of which the individual was normally unaware. Before long, Charcot was postulating the existence of unconscious “fixed ideas” that acted as the nuclei of neuroses. Although there was no developed theory of the unconscious as a whole, there was certainly a growing acceptance that certain mental areas and aspects lay outside individual consciousness.

An important factor that influenced emerging psychological theories was the wave of Spiritualism that crossed the Atlantic from America to sweep nineteenth-century Europe. Techniques like automatic writing, seen by mediums as a method of communication with spirits, were increasingly investigated by neurologists for their insights into the workings of the human mind. Other practices, traditionally associated with spirit contact, included the use of black mirrors, crystal balls, and even bowls of water. One experiment involved the drawing of a white circle on a black floor, then having patients stare at it until they produced a variety of visions and hallucinations. The combination of hypnosis with such techniques virtually guaranteed results, so that by the 1880s, even the founders of the Society for Psychical Research were coming to the conclusion that these methods were more likely to detect hidden contents of a subject’s mind than to communicate with spirits. It was only a matter of time before the new psychology began to investigate mediumship itself.

Among the very first to do so was Theodore Flournoy, a physician, philosopher, and psychologist who held the post of professor of psychology at the University of Geneva in Switzerland. He was a man somewhat interested in psychical research, but he approached the subject from the standpoint of an experimental psychologist. His guiding principle, derived from Hamlet, was “Everything is possible” … but he was careful to add a modification: “The weight of evidence must be in proportion to the strangeness of the fact.” In December 1894, Flournoy was invited by a fellow professor at the university to attended a private séance held by a Swiss medium named Catherine Muller. She was, by all accounts, an impressive figure, a tall, beautiful, thirty-year-old with black hair and eyes, who was so convinced of the truth of Spiritualism that she made no charge for her demonstrations. At the first of these sittings, she certainly impressed Flournoy by telling him accurately of events that had happened in his own family prior to his birth. This seemed, on the face of it, to be information she could not possibly know, but Flournoy was far from satisfied that there could not be a rational explanation. He launched an exhaustive inquiry into Muller’s background and discovered that there had once been a brief connection between her parents and his own. He concluded that she might consequently have heard of the events she mentioned in a wholly explicable way.

Flournoy did not, however, suspect fraud. As a psychologist he thought the more likely explanation was that she had long forgotten the events but somehow accessed the memories in the peculiar atmosphere of the séance. He decided to continue his investigation and became a regular sitter at Muller’s mediumistic demonstrations. Coincident with this decision, Muller’s mediumship underwent a change. In her original sitting, she had remained awake while she described psychic visions of spirits as they arrived and produced raps by which they conveyed messages. Now, however, she fell into a deep trance state and began to recall scenes from previous lives, manifesting personality changes as she did so. Flournoy continued his investigation for five years and subsequently published his findings in a book called From India to the Planet Mars,6 which contained an exhaustive account of Muller’s experiences and an analysis of their content.

What emerged from their collaboration was strange indeed. Muller made contact with a spirit guide named Leopold, an apparent reincarnation of the eighteenth-century Italian magician Cagliostro. The entity frequently possessed her completely during séances and took to advising Flournoy on how he should respond to her revelations. The revelations themselves fell into three distinct cycles. In the first of these, Muller recalled details of a past life in fifteenth-century India where she had lived as an Arab princess Simandini, married to Sivrouka, a Hindu potentate. The life ended when Sivrouka died and Simandini was obliged to commit suttee on his funeral pyre. Muller claimed Flournoy was the reincarnation of Sivrouka and reminded him of several incidents from their life together. The second cycle had an equally unhappy ending: Muller became possessed by the reincarnatory personality of the French queen Marie Antoinette who was executed for treason by guillotine on October 16, 1793. The third cycle was bizarre. It involved life on Mars. Muller claimed to travel there in spirit and knew the planet intimately. She offered proof by describing its terrain and inhabitants: carriages without horses or wheels, emitting sparks as they glided by; houses with fountains on the roof; a cradle having for curtains an angel made of iron with outstretched wings. Its inhabitants were exactly like the people of Earth, apart from the fact—somewhat shocking in Flournoy’s era—that both sexes wore the same costume, formed of ample trousers and a long blouse, drawn tight about the waist and decorated with various designs.

It was a rich vein for analysis and Flournoy mined it thoroughly. He discovered that the main verifiable details of Muller’s Indian incarnation were drawn from a published History of India. Sources for her supposed life as Marie Antoinette were also easy to find. It quickly became apparent that much of the information Muller gave originated in books she had read as a child—and had in all probability forgotten. The vivid landscapes of Mars, he decided, were “romances of the subliminal imagination”7 generated by wish fulfillment and forgotten memories. His investigation further suggested that each “past incarnation” was built upon what he called a “reversion”—an involuntary regression to an earlier stage of life. Her Martian fantasies originated in early childhood, her Indian “incarnation” was built on her personality at the age of twelve, while Marie Antoinette arose out of the girl she was at age sixteen. Flournoy’s analysis of the Martian language that Muller could write as well as speak convinced him that it was structured on French. After his book was published, an expert linguist attested that the content was actually a distorted form of Hungarian, the mother tongue of Muller’s father. The medium’s spirit guide, Leopold, was, Flournoy decided, an unconscious subpersonality of Muller that emerged from its subliminal state, freed by her experience of trance. He concluded that her visions began as “simple entoptical phenomena” produced naturally by the retina and later transformed into full-blown hallucinations under the influence of suggestion. The raps and table movements were, Flournoy thought, probably produced by Muller herself through involuntary muscle movements. He was even more dismissive of Muller’s apparently paranormal abilities such as speaking Sanskrit while manifesting details of her Indian incarnation:

No one dares tell her that her great invisible protector [Leopold] is only an illusionary apparition, another part of herself, a product of her subconscious imagination; nor that the strange peculiarities of her mediumistic communications—the Sanscrit, the recognizable signatures of deceased persons, the thousand correct revelations of facts unknown to her—are but old forgotten memories of things which she saw or heard in childhood.8

Flournoy used this and other investigations to draw far-reaching conclusions about the subliminal mind, mediumship, and spirit contact in general. He was convinced of the extraordinary creativity vested in the subliminal mind: one of his patients was a young mother who proved capable of dictating philosophical fragments far more sophisticated than her apparent level of knowledge would allow. He believed the subliminal mind acted as a compensatory mechanism, pointing to Muller as a well-educated, ambitious woman who, frustrated by her social and economic status, created her elaborate fantasies as a form of wish fulfillment. He believed too that such fantasies often had a playful element. One interpreter of Flournoy’s insights put the case succinctly: “Most mediums do not wish to deceive, they just wish to play, like little girls with their dolls, but sometimes fantasy life gains control.”9

While Flournoy was investigating mediumship in Geneva, Sigmund Freud was beginning to develop his own concept of the unconscious mind in Vienna. Freud himself loathed anything that smacked of the occult, but Jung had no such misgivings and threw himself into the investigation of his cousin’s mediumship with enthusiasm. But it was an enthusiasm tempered by the doctrines of his mentor, Flournoy. Consequently, Jung classified Helene Preiswerk’s mediumistic abilities under four categories: somnambulism, semi-somnambulism, automatic writing, and hallucinations. He attempted to discover the sources of her fantasies and decided one must be Kerner’s work on the Seeress of Prevorst while another was overheard conversations about Kant’s cosmology. Like Flournoy, he attributed table tipping at the séances to the medium herself, thorough “involuntary muscle movements.” One of his more intriguing conclusions was that the Ivenes persona represented Helene as a grown-up and emerged due to an intuition that she would die young. She did, in fact, die prematurely in 1911, from tuberculosis.

Jung’s final conclusions closely mirrored those of Flournoy. His dissertation made frequent use of terms like hysteria and epileptoid. He often referred to the subjects of his study as “patients.” He cited alcohol as a possible factor in one example of the mediumistic phenomenon10 and summed up the entire mediumistic process in the following words: “The impressions received in somnambulism go on working in the subconscious to form independent growths and finally reach perception as hallucinations.”11

The findings of Flournoy and later Jung were accepted almost without question by the emerging discipline of analytical psychology, conventional psychology, and modern scientific thought. Although Jung changed his mind about spirits in later life, the consensus opinion to this day still considers spirits in the same light as Jung and Flournoy did more than a century ago. They are hallucinations of the deep mind. Variations on the theme abound. When the academic Elizabeth M. Butler came to analyze Cellini’s Coliseum conjuration, she reached the conclusion that everything took place exactly as Cellini had described it … but only with qualifications. Her published account of the conjuration begins with the observation that there was a strong visionary element in Cellini’s nature12—and one that did not necessarily represent a clairvoyant perception of spirits. For example, she came to the conclusion that the Ferryman Cellini saw during a life-threatening illness “certainly derived” from Dante’s description of Charon in the Inferno.13 Furthermore, she is happy to call into question the genuineness of the manifestations and the magician involved. In this latter respect she suggested nothing so crude as the magic lantern theory put forward by other commentators14 but rather pointed out that nowhere in the account did Cellini categorically state that he saw or heard the demons personally. If he did not, then, since his companions Romoli and Gaddi were silent on the matter, we rely only on the statements of the magician and, more particularly, the boy Cenci.

Although Butler is fair-minded enough to leave open any question of deliberate fraud, there is little doubt where her sympathies lie when it comes to an explanation:

What are we to think of the good faith of the magician? … He must … have believed in … magic and therefore presumably in his own performances and powers. It seems to me clear that he did; and like many another was hallucinated by his own invocations and the incense.15

It appears, though, that the term hallucinated is not to be taken in the sense it is used by Flournoy and Jung. Cenci’s account is dismissed on the grounds that he was “highly impressionable” and visual imagination is much more vivid in childhood than in later years. Butler suggests that this is the precise reason why children are so often associated with magical experiments of this type. “And it was from Cenci that the panic spread throughout the circle; the magician himself was obviously affected by the terror-stricken boyish voice.”16 So, spectacular though it might appear in Cellini’s account, the Coliseum conjuration really took place only in the imagination of the participants, perhaps with a little mass hysteria thrown in. Views of this type are so deeply embedded that few modern commentators stop to consider those instances of spirit “hallucinations” seen simultaneously by more than one person or recurringly associated with a particular place. An example would be the widely reported “Grey Lady” hauntings of ancient sites throughout the world.