—Benjamin Franklin in Remarks Concerning the Savages of North America, reporting an American Indian’s response to hearing the story of Adam and Eve

No one knows for certain who discovered cider, or exactly where in the world it was first made and consumed. In part this is because of cider’s sheer antiquity, its origins lost, like so many early human developments, in the mists of prehistory. In part it is also due to the widespread distribution of apples throughout the world’s temperate growing regions. And because there would be no cider without apples, to really understand the history and development of cider and cidermaking, it is essential to know a little about where the apple comes from and how it has evolved.

Of all the fruits of this earth, few have been more celebrated than the apple, few have been cultivated more widely, and few have had a longer history of use and enjoyment, especially among the great civilizations of Europe and Asia. In recent centuries, as conquerors and colonists migrated from the Eurasian continent to the four corners of the globe, the apple invariably went along for the ride—either in the form of seeds, which spawned new and unique varieties, or as grafted trees or scions (cuttings) taken from old and valued parent strains.

The species that we now know as the cultivated apple (Malus pumila, or M. domestica) probably arose in the valleys and rugged foothills of the Tien Shan Mountains, in the border country between northwest China and the former Soviet republics of Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. In fact, the Kazakh capital’s name, Alma-Ata (or Almaty), means literally “father of apples.” From this mountainous region to the shores of the Caspian Sea, plant researchers have discovered wild groves of the domestic apple’s main ancestor, M. sieversii. The trees and fruits of this one species are incredibly diverse, in many respects similar to the wide range of today’s cultivated apple varieties. Scientists are still debating how much or how little other wild species of apples might have contributed to the genetic makeup of our modern apple. These include the bitter-fruited M. orientalis, which hails from the Caucasus region, and the European crab apple, M. sylvestris, whose native range stretches from the British Isles to Turkey.

Phil Forsline, curator emeritus of the apple collection at USDA’s Plant Genetic Resources Unit in Geneva, New York, discusses apple trees grown from seeds collected in Central Asia (background), with a group of visitors.

Back in September of 2005, I had my first opportunity to tour the large and impressive Central Asian apple collection at the USDA’s Plant Genetics Resources Unit in Geneva, New York, which for more than a century has been the center of apple research in America. My guide was Dr. Phil Forsline, who had traveled to the former Soviet Central Asian republics beginning in the late 1980s and had brought back seeds and cuttings of wild apple trees from a variety of locations and climates, from mountains to deserts. To see these mature trees fruiting today in western New York State is a wonderful experience, and it illustrates dramatically just how diverse M. sieversii can be. Although the majority of apples were small, yellow, and often quite bitter or astringent (great for cidermaking!), there were also a few “elite” varieties that could just as easily have been brought to the market and sold for eating out of hand, with little or no improvement needed. The fact that some wild apples could be so large and tasty was a revelation to me, and demonstrated just how efficiently natural selection can work over thousands of years, even in remote regions where humans haven’t been living or farming. In a 2006 book, authors Barrie Juniper and David Mabberley suggest that bears and horses, not humans, were chiefly responsible for the selection, improvement, and dispersion of the wild apple.1 Today the goal, at Geneva and elsewhere, is to revisit the genetic roots of the apple, and to use the ancestral M. sieversii and other species to breed greater disease resistance into our own cultivated apples, creating new varieties that will require far less spraying, chemical or otherwise.

Even before the modern apple became widely known in Europe and Asia, there is evidence to suggest that various indigenous peoples were already making extensive use of wild apples. Wild apples were depicted in Paleolithic cave art that dates from between 35,000 and 8000 B.C., and archaeologists have found the carbonized remains of apples in Anatolia dating back to 6500 B.C., and at the sites of Neolithic lake settlements in what is now Switzerland and Italy, which were occupied between 2000 and 1600 B.C.

How these ancient peoples used apples is more a matter of conjecture than scientific fact. It seems likely, however, that they would have sampled fruit from all kinds of apple trees, selecting those apples that tasted sweetest and most palatable. And it isn’t much more of a stretch to imagine how these earliest orchardists first discovered cider, as wild yeasts that are found everywhere (in the air, on the ground, and on the skins and flesh of apples) will go to work on apples naturally and begin the process of fermentation. They would have found, as the naturalist Henry David Thoreau did in his rambles around Walden Pond, that even the sharpest apples mellow nicely with age—especially after the first winter frosts:

Those which a month ago were sour, crabbed, and quite unpalatable to the civilized taste, such at least as were frozen while sound, let a warmer sun come to thaw them—for they are extremely sensitive to its rays—are found to be filled with a rich, sweet cider, better than any bottled cider that I know of, and with which I am better acquainted than with wine. All apples are good in this state, and your jaws are the cider-press… . It is a way to keep cider sweet without boiling. Let the frost come to freeze them first, solid as stones, and then the rain or a warm winter day to thaw them, and they will seem to have borrowed a flavor from heaven through the medium of the air in which they hang.2

Prehistoric peoples doubtless would have tasted this kind of natural cider. But we can also imagine other scenarios that might have led them to an understanding and appreciation of alcoholic, or hard, cider. Perhaps some band of hunter-gatherers drank a bit of the clear liquid that pooled in the hollow of a tree beneath a heap of partially crushed apples. We can only guess what that first sip must have tasted like to them: Did they hear the angels sing, or did they spit out the fizzy, tangy stuff? Regardless, it seems reasonable to assume that cider was probably discovered many times over, by many indigenous peoples, in almost every region of the world where apple trees were growing wild.

Around eight thousand years ago, with the development of agriculture and the rise of the first great cities and civilizations, apples began to appear both as an article of trade and as a cultivated crop in the ancient world. While the climates of Egypt and the Tigris-Euphrates Valley were probably not cool enough to grow apple trees successfully (at least on any large scale), there is ample evidence that apples were imported by caravan along the long-distance trade routes that wound all the way from India and China to the eastern Mediterranean. These silk and spice roads passed directly through the apple’s Central Asian homeland, and before long the virtues of the fruit had led to its cultivation in many lands, including Persia, Asia Minor, and northern Mesopotamia. Apples were celebrated by the earliest writers, both popular and agricultural. Homer mentions them in The Odyssey, when the wandering hero Odysseus sees them growing in the gardens of Alkinöos, king of Phaiakia. The fruit was also said to have been a favorite dessert of Philip of Macedon and of his son, Alexander the Great. It was a custom they probably picked up from the Persians, who regularly served apples along with other fruits as a final course at their banquets. In fact, by imperial Roman times, apples had become such a common fixture at meals that they gave rise to the proverbial Latin expression ova ad malum (“from the egg to the apple”), which implied the whole progression of a meal or, by extension, the whole scope of any event. Today we would say “from soup to nuts” to convey the same idea, but back then eggs were customarily served as the first course at a Roman meal, and apples as dessert.

The first recorded references to cider also date back to Roman times. In 55 B.C. Julius Caesar began his conquest of Britain, where his soldiers found the Celtic inhabitants fermenting the juice of the native crab apples to make an alcoholic beverage. The Roman legionnaires and administrators who subsequently settled in portions of Gaul (present-day France) and Britain are credited with having introduced several cultivated varieties of apples, at least one of which has traditionally thought to have survived to modern times: the Court Pendu Plat, also known as the Wise Apple because it blossoms very late, thus “wisely” avoiding early spring frosts. (Another very old Breton variety, the Pomme d’Api, or Lady apple, was long associated with the Appia variety of Roman times, though modern European authorities doubt there is any connection).3 Even more importantly, though, the Romans brought with them their horticultural knowledge, and introduced orcharding techniques like grafting and pruning, which they in turn had picked up from the Greeks and the Syrians. And, as the Spanish writer Eduardo Coto has pointed out to me, some of the Roman soldiers who settled in Britain probably came from the region of northern Spain, where a local cidermaking culture was already developing at around this time.

By the second and third centuries A.D., Roman authorities reported that various European peoples were making a number of more or less ciderlike drinks (pomorum), created from different types of fruit, that were reportedly similar to grape wines and in some cases superior to them. In the fourth century, Palladius wrote that the Romans themselves were making perry, or pear wine, and Columella listed thirty-eight different varieties of pears and twenty-four varieties of apples. Around the same time, Saint Jerome used the term sicera to describe fermented apple juice, from which we derive the word cider. Sikera was actually a Greek word meaning simply “intoxicating beverage,” and it comes in turn from the Hebrew word sekar (which some people also believe to be the root of the slang term schnockered, indicating someone who has tippled too much.)

With the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the fifth century A.D., the horticultural arts entered a period of decline in many parts of Europe. Fortunately, along with other fields of knowledge, the skills of grafting, pruning, and fruit growing were preserved during the Dark Ages by the Christian monastic orders. Monastery gardens featured many types of edible and useful plants, and the rise and spread of the Church’s influence encouraged the large-scale planting of fruit trees and vines on abbey lands.

At the same time, the Islamic Moors, who ruled much of Spain until the late fifteenth century, established impressive botanic gardens and built on the knowledge of classical authors, developing new varieties and techniques that greatly influenced those gardeners who followed them. In fact, we probably have Spaniards to thank for developing many of the classic bitter, high-tannin apples that still make the richest, most distinctive ciders. For although most cider drinkers in North America, through cultural familiarity, consider French and English hard ciders the finest in the world, the people of northern (non-Moorish) Spain were evidently making sidra, or cider, long before the birth of Christ. With a moderate climate similar to that of our Pacific Northwest—one where apple orchards mingle with orange groves—the coastal regions of Asturias and the Euskadi, or Basque country of Spain, represent perhaps the oldest apple-growing lands in Europe.

Many of the apples grown at this time were seedlings. Yet cultivated apple varieties rarely, if ever, resemble their parents when grown from seed. Seedlings from large apples may produce small fruit; seedlings of red apples may have green or yellow fruit; and seedlings of sour apples may bear much sweeter fruit. For this reason, apple varieties that were considered especially valuable for eating or culinary use would usually have been propagated vegetatively by grafting, while less choice or less palatable fruit from seedling trees would have been pressed into cider.

Given this fact, it is somewhat curious that a strong cider-drinking culture developed only gradually in northwestern Europe, over a period of several centuries. It is true that the emperor Charlemagne issued an edict stating that brewers, including cider- and perrymakers, should be encouraged to develop their trade. And in Franconia, the region in modern-day central Germany, a cidermaking tradition did become established as a part of estates and monasteries, one that continues even to this day, with both craft and commercial producers making cider, albeit under different names like Apfelwein, Most, and Viez.4

Yet even in Normandy, which would become one of the world’s most celebrated cidermaking regions, cider was widely consumed before the twelfth century only in years when there was a shortage of beer or other drinks brewed from grains and herbs, which were the most common beverages at the time. Not until the fourteenth century did cider become as popular and available as beer and wine in Normandy. By 1371, however, almost as much cider was being sold at Caen as wine, and some of it was being shipped up the Seine to the Paris market.

Cider in Normandy was subject to heavy taxation during the disastrous Hundred Years’ War between England and France (1337–1453), but in the century following the wars its popularity spread greatly. In 1532 Francois I toured Normandy and ordered several barrels of cider made from the Pomme d’Espice apple for himself. At Val-de-Seine in the Contentin region, a gentleman named Guillaume Dursus began studying the different kinds of cider apples and assembled a collection of those he considered the best varieties, taking the grafts from his home in northern Spain. And in 1588 Charles IX’s physician, a man from Normandy named Julien le Paulmier, published a treatise entitled De Vino et Pomaceo, in which he listed some eighty-two varieties of cider apples. Paulmier’s work helped to increase the popularity of cider over a much broader area of France and encouraged its sale.

During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the production of cider spread from Normandy to other parts of France: Brittany, Maine, Picardy, Île-de-France, and Orléans. In the eighteenth century, agricultural societies were formed that encouraged the production of cider and cider apples by sponsoring prizes and competitions. Beginning in 1863, grapevines in French vineyards suffered extensive damage from phylloxera, an insect related to aphids. By the time the destruction had run its course, and the great vineyards were replanting European wine grapes grafted onto insect-resistant American rootstocks, the French interest in cider was beginning to grow. Eventually, by the end of the nineteenth century, the French government estimated that more than one million persons were engaged in cidermaking; by 1902 the nation was producing around 647 million gallons commercially (that is, not counting what farmers were making and drinking themselves).

On their arrival in Britain the Romans found the inhabitants making cider, presumably from the European crab apple (Malus sylvestris), which had been growing wild there since Neolithic times. Evidence at the Windmill Hill archaeological site in Wiltshire suggests that the ancient Britons used apples for food, though they seem to have relied mainly on wild trees rather than planting them to any great extent. However, the Roman introduction of cultivated apples and horticultural know-how soon led to the first orchards being established in England.

This situation changed drastically with the fall of Rome, and orchards were abandoned as a succession of invaders—Jutes, Saxons, and Danes—attacked British towns and settlements. As in the rest of Europe, though, the spread of Christianity helped to keep both knowledge and useful arts alive in the monasteries. The monastery at Ely in Cambridgeshire was especially famous for its orchards and vineyards, and a twelfth-century plan of the Christ Church monastery in Canterbury shows its pomerium, or apple garden, where apples and pears were grown for both eating and pressing into cider and perry.

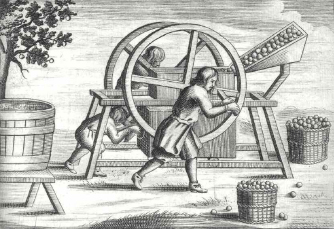

The Ingenio mill, used for grinding apples before pressing, was invented by the Englishman John Worlidge and depicted in his 1676 book, Vinetum Britannicum.

The Norman Conquest in 1066 sparked a new interest in cider in England. The Normans introduced many apple varieties, including the Pearmain, a long, pear-shaped apple that was the first named variety recorded in Britain. Around 1120, William of Malmesbury described extensive orchards and vineyards that were being grown at Thorney, Isle of Ely.5 Cider soon became the most popular drink after ale, and it began to be widely used as a means of exchange to pay tithes and rents. A deed of 1204 stipulated that the tenancy of the manor of Runham in Norfolk would bring in an annual rent of “200 Pear-maines and four hogsheads of Pear-maine cyder,” payable to the Exchequer every Michaelmas (September 29) by Robert de Evermore, the lord of the manor. A hundred years later, seventy-four of the eighty parishes in West Sussex were paying their church tithes in cider.

As early as the reign of Henry III in the thirteenth century, the borough of Worcester had already become famous for its fruit trees and cider orchards. By the end of that century, a number of choice apple varieties had been collected in the royal gardens at Westminster, Charing, and the Tower, as well as in the gardens of English noblemen. In the main apple-growing counties of the time—Kent, Somerset, and Hampshire—most manors had their own cider mills and were pressing their own cider.

In the early sixteenth century, cider lost some of its popularity in relation to ale when hops were first introduced to England from Flanders. Hops greatly improved the flavor, as well as the keeping qualities, of British ale. Yet around the same time, Richard Harris—fruiterer to Henry VIII—advanced the cause of British apple-growing when he reportedly “fetched out of France a great store of grafts, especially pippins [a dessert apple also suitable for cidermaking], before which there were no pippins in England.” These trees, along with other fruits, were planted in an orchard of about 140 acres at Teynham in Kent.

The famous cider orchards of England’s West Country became increasingly well established during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, particularly in the counties of Herefordshire, Gloucestershire, and Worcestershire. By the end of the seventeenth century, cider was being produced throughout much of southern England, including the West Country, West Midlands, Devon, Somerset, Shropshire, and the Welsh border counties. This century has been called the Golden Age of Apples in England, and the county of Herefordshire in particular was described at this time by John Evelyn as having “become in a manner but one entire orchard.”

Adding to the growing fame of Herefordshire’s cider was the celebrated Redstreak apple, which, it is said, grew from a seed planted by Charles I’s ambassador to France, Lord Scudamore, on his estate at Holme Lacy. Scudamore was one of the many Royalist nobles and gentlemen who had retired to their country homes after fighting in the English Civil War, and who spent the years of the Protectorate cultivating their gardens and identifying new and interesting varieties of fruit—all in all, a very productive and civilized way to pass the time during a period of social upheaval and internal exile.

The keen interest in identifying and improving cider-apple varieties in the seventeenth century led to both technological advancements and a marked improvement in the quality of cider. John Worlidge, in his Vinetum Britannicum (1676), listed useful cider apples, and other amateur cidermakers also kept careful records about the relative merits of single-variety ciders and blends. Lord Scudamore is credited with having bottled cider as early as the 1640s at Holme Lacy, at a time when almost all cider was stored in wooden barrels and drawn off “on draft” as needed. Scudamore made use of the new, stronger, coke-fired English glass bottles that had been recently introduced. The slight fermentation that took place in the bottles released carbon dioxide gas, which produced a sparkling drink and helped preserve the cider better than could half-emptied wooden casks or barrels, where aerobic organisms came in contact with the cider and often spoiled it.

The rich soils and the mild, moist climate of England’s West Country made this region an ideal place to grow apple and pear trees, and cidermaking in general fit extremely well into Britain’s farm economy of the seventeenth century. Productive, low-maintenance, and long-lived, apple trees were set out widely spaced in the field or orchard, with either crops or sod grown among them, the latter for pasturing dairy herds. Most cider apples didn’t need to be picked until October or later, by which time other crops had been harvested and the farmer had a bit of leisure. Once pressed into cider, the leftover apple pomace could be soaked with water and pressed again to make a weak “water-cider” or “ciderkin,” then finally used as a feed for livestock. Farmworkers received a cider allowance as part of their wages, typically 2 quarts a day for a man and 1 quart for a boy. This practice dates back to at least the thirteenth century, when workers in monastery orchards were paid in cider, and it continued for nearly five hundred years, until it was finally declared illegal in 1878.

Two other factors that encouraged cider production in England at this time were the shortage of burnable wood and international trade restrictions. To brew ale required fuel for heat, both to malt the barley and to boil the wort before fermentation; the cidermaking process, on the other hand, didn’t require heat. Wood in England was in very short supply, so planting fruit trees made doubly good sense: There were apples and pears for making cider and perry, plus wood from old trees for fuel and other uses. By 1615 the national timber shortage had also led to a ban on the use of charcoal for iron smelting and glassmaking, prompting innovators like Robert Mansell and Sir Kenelm Digby in the 1620s and 1630s to develop stronger coke-fired glass, as mentioned above.6 Add to this the shaky international relations between England and other European nations, particularly wine-producing countries like France and Germany, and it’s easy to see why hard cider came to be seen not only as a refreshing and wholesome draft, but even as a patriotic national beverage.

John Worlidge’s design for a continuous cider press, from Vinetum Britannicum (1676).

By the eighteenth century, the English thirst for cider had become prodigious. According to the novelist Daniel Defoe, some ten to twenty thousand hogsheads of cider (between 1 and 2 million gallons) were exported from the area around the port of Exeter during the 1720s, and the construction of canals enabled merchants to transport cider in bottles to London and other markets.

Ironically, the very popularity of cider in England helped contribute to its decline during the middle part of the eighteenth century. Up until this time, cidermaking had largely been a rural practice engaged in by farmers, who produced a rough cider for home use and local sale, and by landed gentlemen, who had the leisure and resources necessary to experiment with different apple varieties and production techniques, in an attempt to match or even surpass the quality of imported wines. But with the initial stirrings of the Industrial Revolution and the movement of workers off the farms and into the cities and factories, the quality of English cider began to decline, even as demand remained strong. Unscrupulous cider merchants began buying large volumes of sweet, unfermented juice and producing adulterated or watered-down beverages that resembled real cider in name only. The “Devonshire colic,” a palsy-like sickness caused by lead leaching into cider from the joints and pipes of manufacturing equipment, further damaged cider’s reputation, as did the rough drink known as scrumpy, which was sometimes made from rotten fruit, other fruit juices, surplus vegetables, sugars—just about anything that would ferment. The new British ales like Whitbread, Bass, and Guinness were seen, quite rightly, as more healthful than these degraded ciders, which came to be considered a beverage of the urban lower classes and as a cheap, quick way to get drunk.

The illustrations opposite the title page of John Worlidge’s influential Vinetum Britannicum (1676) show his designs for “modern” cidermaking technology, which has not until recent years changed very much.

The first attempt to revive the popularity and good name of English cider occurred near the end of the eighteenth century, when the famous plant breeder Thomas Andrew Knight published his Treatise on Cider, and then, in 1811, the Pomona Herefordiensis, which included information on all of the cider apples and perry pears grown in the county of Hereford. Around this time many English apple varieties, particularly the Golden Pippin, were seriously afflicted with diseases such as apple canker. Knight began to make intentional crosses between different varieties in an attempt to create new apples and halt the decline, and this sparked a new wave of interest in fruit breeding during the nineteenth century, encouraged by the activities of the Royal Horticultural Society and other groups.

In the late nineteenth century, the character of English cider began to change, as small regional cidermaking gave way to a more centralized, industrial system of production. Between 1870 and 1900, more than a dozen cider factories opened around Herefordshire, including H. P. Bulmer Ltd., which was founded in 1887 by Percy Bulmer and grew to become the largest cidermaker in the world, marketing no fewer than seventeen brands and accounting for more than half the cider consumed in Britain.

Not surprisingly, the apple was one of the first crops introduced to American shores by colonists from England and western Europe. Although a few species of small wild apples are native to North America, such as the garland or sweet crab (Malus coronaria), the prairie crab (M. ioensis), and the southern crab (M. angustifolia), it is not clear to what extent they were used by the Native Americans. However, the first cultivated apple trees were planted in Boston (at that time known by its Indian name of Shawmut) as early as 1623 by William Blackstone (or Blaxton), a dissident Church of England clergyman and a minister to the settlers at Plymouth.

Tradition has it that Blackstone was something of an eccentric character and that he once saddle-trained a bull, which he rode around the countryside, distributing apples and flowers to his friends. Like so many free spirits of the time, Blackstone apparently ran afoul of the British colonial authorities, so in 1635 he moved to Rhode Island, planting his first orchard there and introducing what, by some accounts, was America’s first native apple variety, Blaxton’s Yellow Sweeting. Others bestow this honor on Roxbury Russet, a greenish-yellow apple with a rough skin (another common name is Leathercoat), whose original tree was discovered sometime before 1649 on a hill in Roxbury, Massachusetts, near Boston. More than 350 years later, it’s still grown and is still a fine multipurpose apple.

To the settlers of this new country, the apple represented the perfect homestead fruit. An apple tree, once it began to bear, would dependably produce bushels of fruit that could be used immediately for eating or cooking. Some varieties, like

Roxbury Russet, could be stored in a cold cellar and kept all winter long, while others, like the old Hightop Sweet apple reputedly grown at Plymouth Plantation, could be sliced and dried for later use. But cider played the most crucial role in America’s rural economy, as pressing and fermenting the fresh juice of the apple was the easiest way for farmers to preserve the enormous harvest that came from even a modest orchard. Cider was also the basis for many other products, such as applejack, apple brandy, and cider vinegar, which was used to preserve other fresh foods and for myriad other purposes around the home.

Apple trees grown at Geneva, New York, from seeds collected in Central Asia.

Americans planted apples wherever the climate allowed, from the New England colonies to the mountains of northern Georgia. In 1647 apples were being grafted onto wild native rootstocks in Virginia, and in the same year the first grafted tree arrived from Europe—a variety imported from Holland known as the Summer Bonchretien, which was planted by Gov. Peter Stuyvesant in New Amsterdam. Stuyvesant’s farm was located in the Bouwerij (Bowery) district, and the trunk of this historic apple tree remained standing on the corner of Third Avenue and Thirteenth Street in New York City until 1866, when it was broken off by a cart.

While well-to-do planters and colonial officials could afford to import grafted stock from Europe, much of the apple’s spread in America was by seed, which could be easily carried and planted by settlers pushing inland and westward. Many farmers spread pomace (the seeds and skins left over from pressing cider) onto their fields, then took grafts from any seedlings that sprang up and bore good fruit.

The American folk hero Johnny Appleseed became a symbol of the apple’s spread as it followed western settlement in the years after the Revolutionary War. Born in Leominster, Massachusetts, in 1774, the historical Appleseed’s real name was John Chapman. In the first half of the nineteenth century, Chapman did operate an extensive frontier nursery in the Susquehanna Valley of Pennsylvania, from which he traveled as far afield as Ohio and Indiana, preaching, planting apple seeds, and selling seedling trees to settlers, who were eager to install such familiar and useful domestic plants, and to demonstrate that they were improving their homestead land grants.

Because these seedling trees produced fruits that were unlike the apples they came from, new types of American apples quickly emerged, many of them unnamed varieties and unique to a particular farm or estate. By the early 1800s, American nurserymen were already offering around one hundred named varieties of apples for sale; by 1850, more than five hundred widely recognized varieties were being cultivated; and in 1872 Charles Downing’s Fruit and Fruit Trees of America listed close to eleven hundred different kinds of apples that had originated in America.

French Huguenots who settled in New Rochelle, New York, and along the northern shore of Long Island also brought with them a wide variety of fruits. Around 1730 Robert Prince established Prince Nurseries in Flushing, not far from the spot where the first commercially important American apple, the Newtown Pippin, originated. By 1845 the Prince catalog, which purported to offer only the best kinds of apples, was listing 350 varieties. Even though many farmers relied on seedling trees, the familiar and proven varieties offered by nurseries were popular among home orchardists, then as now. Farmers would “top-work” their trees, sometimes grafting many varieties onto a single trunk. The ultimate goal for homesteaders was “to furnish the home with fruit from the first of the season through the autumn, winter, and the spring, and even till early summer.”7

By 1775 one out of every ten farms in New England owned and operated its own cider mill. There are numerous reasons why cider, like the apple itself, flourished in the American climate. For one thing, most early settlers preferred not to drink the local water, which could be unpalatable or even—close to settlements—polluted. This left milk and alcoholic beverages, but importing such a staple as ale from England was expensive and chancy, and early attempts at growing barley and hops in New England had proved a dismal failure. For a time, desperate colonists sought creative, if dead-end, solutions to the problem, brewing beers out of pumpkins, corn (maize), molasses, maple sap, and even native American persimmons.

The Harrison apple, renowned in early America for making superior cider, was considered extinct until the 1970s and ‘80s. Modern cidermakers are now rediscovering and replanting this fine old variety.

Apple trees, however, could be grown almost everywhere in America, and it didn’t take long for the colonists to put down their persimmon beer and take up cidermaking in earnest. Consumed by men, women, and children, by hired hands and Harvard students, cider quickly became America’s national drink. In 1726 it was reported that a single village near Boston, consisting of about forty families, put up nearly 10,000 barrels of cider. One historian stated that in the year 1767 a per capita average of 1.14 barrels of cider was being consumed in Massachusetts; that amounts to more than 35 gallons per person. President John Adams drank a large tankard of cider every morning until the end of his life, believing (probably correctly) that it promoted good health. One “Lazarus Redstreak” argued in 1801:

Experience shows that the use of [cider] consists with sound healthy and long life. Our inhabitants are settled in favour of it. The New Englanders are of all people the longest livers. Why then try an innovation so difficult, so doubtful, to say the least, in point of health and economy, as the substitution of beer in the place of cyder?8

Because it was so widely available and such a useful commodity in daily life, and because currency was relatively scarce, especially in rural areas, cider became a common unit of exchange, as it had been earlier in England. It was frequently used by farmers to pay the doctor, the schoolteacher, the minister, and other local professionals for their services. As it was plentiful, cider also tended to be quite inexpensive. The seventeenth-century historian John Josselyn wrote, “I have had at the tap houses of Boston an ale-quart of cyder spiced and sweetened with sugar, for a groat” (about fourpence), and in 1740 a barrel of cider cost about three shillings.9 More than seventy years later, in 1817, the American pomologist William Coxe reported that cider in the Middle Atlantic states was selling for about five dollars per hogshead, and he advised cidermakers to convert part of their supply into vinegar, which would fetch three times the price of hard cider.

Although cidermaking was commonplace throughout America, the best quality of cider and the greatest commercial quantities were being made in New Jersey, especially in Newark. Local cider apples included the Harrison, which produced a cider described as having a “high colour, rich, and sweet, of great strength, commanding a high price in New York.”10 The Shaker community in Canterbury, New Hampshire, was making cider of such high quality that it sold in Boston for as much as ten dollars a barrel. In his 1817 book, A View of the Cultivation of Fruit Trees, William Coxe gives some indication of just how much cider (and cider brandy) was being made in its heyday:

In Essex county, N.J. in the year 1810, there were made 198,000 barrels of cider, and 307,310 gallons of cider spirits were distilled—one citizen of the same county in 1812, made 200 barrels of cider daily through a great part of the season, from six mills and twenty three presses. In the present season, 1816, 25,000 barrels of cider were made within the limits of a single religious society, as it is called, in Orange township, Essex county New-Jersey; comprising about three fourths of the township.11

An interesting footnote to this account is that 1816 came to be known as the Year without a Summer, due to an unusual global cooling event that occurred after the massive 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora in the Dutch East Indies. Killing frosts struck the northern United States and Canada in each of the three summer months, mowing down corn and other field crops and causing food shortages in North America and actual famines and bread riots in parts of Europe. On the bright side, though, the cold temperatures also decimated the insect population that year, resulting in one of the best apple crops ever.

American apples and cider were also being exported to the West Indies, and even to Europe. The first recorded shipment of apples from New England to the West Indies occurred in 1741. In 1758 a package of Newtown Pippins was sent across the Atlantic to Benjamin Franklin in London. And in 1773, when the English apple crop failed, merchants imported great quantities of American fruit.

Virginia fruit historian and orchard consultant Tom Burford, who helped rediscover and repopularize the famous Harrison apple.

Back at home, cider even played a part in American politics. When George Washington ran for the Virginia legislature in 1758, his agent doled out nearly 3 imperial gallons of beer, wine, cider, or rum to every voter. In the presidential campaign of 1840, Whig candidates William Henry Harrison and John Tyler, whose famous slogan was “Tippecanoe and Tyler too,” played to anti-immigrant sentiments and used the symbols of the log cabin and cider barrel to represent self-reliance and traditional American values. Cider was freely served to all voters, and the Whigs won in an electoral landslide, 234 to 60.

Yet by this time cider’s place in American culture was already starting to wane, and as the nineteenth century progressed, several independent and unrelated forces combined to weaken its standing still further. One major factor was urban migration. In 1790 the United States was an agrarian nation: Some 96 percent of Americans lived on farms and raised most or all of their own food; only 4 percent lived in towns or cities. By 1860, 84 percent still lived on the farm. But forty years later, this rural population had dropped sharply, to 44 percent, and by 1910 only 30 percent of Americans were still on the farm.12

Until around 1850, apple growing and cider-making remained closely linked to the small, self-reliant homestead farm, but the migration of workers to cities and to the fertile lands of the West after the Civil War meant that many old orchards were abandoned. Also, homemade farm cider, which was unfiltered and unpasteurized, didn’t travel well to the new centers of population. Coupled with this growing urbanization and resettlement during the late nineteenth century, a steady stream of immigrants from Germany and northern Europe led to the establishment of more breweries in America and the increased consumption of beer, especially in cities.

At around the same time, in 1848, the first apple trees were being planted in central Washington State by a territorial legislator named Hiram F. “Okanogan” Smith. More than a century and a half later, the orchards of Washington now produce about half of the U.S. apple crop (or about 5 percent of the world harvest), but these apples are grown intensively for fresh shipping, not for cider. And although the planting of commercial apple orchards in western New York and other areas of the East also continued during the 1850s, growers were beginning to get discouraged by greater damage from insects like the codling moth and diseases like apple scab. This led to the widespread cutting of orchards during the 1880s and a greater reliance on arsenical insecticides and fungicides.

Even more damaging to cider, though, was the rise of the temperance movement, whose members considered the beverage once hailed as safe and wholesome even for children to be little better than demon rum. In fact, American cidermakers had for a long time been increasing the “octane,” or alcoholic content, of natural cider (which normally ferments to around 6 percent alcohol, much lower than grape wines). At first this was done to improve the keeping qualities of cider, especially cider that was intended for long-distance shipping or export. Producers increased the final strength of the cider much as they do today, by adding a sweetener (honey, sugar, raisins, and so on) to the juice before or during fermentation. By the late eighteenth century, the alcohol content of the standard cider sold in taverns ran around 7.5 percent—still not producing that much of a kick. Some producers, however, added rum to their rough cider, making it a less than “temperate” beverage. Also, the impurities found in traditional applejack (a strong, concentrated liquor that was made by freezing hard cider outside in the winter) gave drinkers awe-inspiring hangovers and, over time, led to the unfortunate condition known as apple palsy. Finally, just as had happened earlier in England, the good name of cider was besmirched by unscrupulous manufacturers, who made it out of just about anything, as is evident from this commentary from 1890:

Traditional European cider apples at harvest time, western New Hampshire.

The Baldwin apple, prized for cider use, was once a leading commercial variety in the U.S. However, many trees died in the bitterly cold winter of 1933–34, and it was largely replaced by the hardier Mcintosh.

The writer has found, by oft-repeated trials, that it [cider] is the most difficult of all articles to obtain in saloons, restaurants, and groceries. All keep an article they sell for cider; but in many cases it has but a small portion of fermented apple-juice, while in others there is no trace of the apple, the stuff sold being a villainous compound of vinegar, glucose, whisky, and pepper. Now it is perfectly patent that such a concoction could never be sold in this country for cider, any more than it could be sold in France for wine, if the knowledge of the true article prevailed here as does that of true wines in that country. But before such knowledge can prevail here, the cider makers must learn how to make cider correctly. There is where the fault lies, and the consumers will learn their part fast enough when a fairly good article is offered for their acceptance.13

Many farmers sympathetic to the temperance cause took axes to their apple trees and swore off alcoholic beverages of any kind. Others, not quite so fervent, started pasteurizing their pressed sweet cider and marketing it as inoffensive apple juice, or calling the fresh, unfermented juice from the press “sweet cider,” a term that has been the cause of much confusion since then. Another blow came during the unusually frigid winter of 1917–18, when temperatures in the Northeast plummeted, wiping out whole orchards of cider apples, including an estimated one million Baldwin trees. (The winter of 1933–34 was equally hard, with -40°F weather sounding the final death knell for the Baldwin as the leading commercial apple; after this, many farmers replanted their orchards with the hardier McIntosh variety.) By the time Prohibition was enacted in 1919, the production of hard cider in the United States had dipped to only 13 million gallons, down from 55 million gallons in 1899. Over the next several decades, the once proud American tradition of making hard cider was kept alive only by certain local farmers and enthusiasts.

Yet today, after a long hiatus, Americans are once again developing a taste for hard cider. In 2004 hard cider consumption in the United States exceeded 10.3 million gallons, up from 5.3 million gallons in 1996 and just 271,000 gallons in 1990. Demand for cider is also growing in traditional producing countries like England (which produced some 130 million gallons in 2006) new markets like China (the world’s largest apple-growing nation), and elsewhere around the world. Yet cider is still a relatively minor player in the overall alcohol industry, equivalent to only about 0.3 percent of the total U.S. beer and flavored malt beverage market in 2012..

So what does the future hold? It really is anyone’s guess, but there are encouraging signs. Increasingly these days, small orchardists and serious cidermakers in the United States are planting distinctive European cider apples and experimenting with both traditional and newer American varieties to see which are the best for making cider. Over the past few years it has become easier and easier for cider lovers to find high-quality beverages made by regional cider mills and wineries. And in the twenty-first century, blessed and encumbered as we are with our Information Age technologies, it’s nice to know that something as old and traditional as the art of cidermaking is not only alive and well, but flourishing.

As its name implies, False Major resembles the true English bittersweet Major, but somehow got confused in translation. It’s still a useful cider variety.