CHAPTER 2

EARLY WARNINGS

IVÁN VELÁSQUEZ DIDN’T LIKE TO drive, so his wife, María Victoria, usually took the wheel. That Saturday in October 1997, she was driving Velásquez and their three kids on a day trip out of Medellín. Catalina, then seventeen; Víctor, fourteen; and Laura, nine, had piled into the back of the car, and the family had started to make its way along the Las Palmas highway, snaking up the tall mountains embracing Medellín.

Except during the rainy season, Medellín was nearly always sunny and warm, a messy, heavily trafficked, polluted city sitting in the bright green Aburrá Valley, which was dotted with shiny yellow guayacán trees and luxuriant bougainvillea vines. Butterflies and a large variety of birds—egrets and crakes, osprey and kestrels, warblers, various hummingbirds, cuckoo birds, and even macaws and occasional flocks of parakeets—regularly visited the city’s many gardens and parks, which provided much-needed relief from the concrete jungle at Medellín’s center. Today was another bright day, and Velásquez was enjoying being with his family again.

Velásquez had just started a new job as chief prosecutor for Antioquia and the neighboring states of Córdoba, Caldas, Risaralda, and Chocó. He had not, at first, been at all interested in the job. Regional prosecutors at the time were known as “prosecutors without a face,” meaning that—for their own security—they operated anonymously; neither defendants nor witnesses knew their names. To Velásquez, the idea of anonymous prosecutors seemed deeply unfair; defendants should be able to see those who were accusing them of crimes.

But he had been living far from his family, working eight hours away, in Bogotá, for over a year. María Victoria’s job was in Medellín, and she didn’t want to quit and have to hunt for new employment in a strange city. Velásquez would sometimes meet María Victoria and the kids in a relative’s cottage halfway between Bogotá and Medellín for a weekend, and then, on Sunday afternoon, wave longingly through the window as Catalina, Víctor, and Laura settled into María Victoria’s car to drive back to Medellín. When the kids were smaller, he had always been deeply involved in caring for them: preparing their food, taking them to school, playing with them. But more and more, Velásquez feared his kids were growing up without a father, and he worried about the harm the distance might do to his relationships with his children and wife. So when a colleague had suggested him for this position, he had agreed to consider it—and eventually accepted.

Velásquez’s office had assigned him the bulletproof car they were in, saying he must use it for his own security: any number of people could want the chief prosecutor dead. Velásquez had agreed without thinking too much about it; security concerns were not new to him.

ONLY A FEW years earlier, Velásquez had been stuck between two warring factions during some of the worst violence Medellín had ever experienced. He was serving as inspector general for the city, charged with monitoring abuses by public officials, in the final years of the drug war that cocaine kingpin Pablo Escobar was waging against the Colombian government.

Even as Colombia’s war between guerrillas and the government churned, during the 1970s and 1980s, Colombia had become the epicenter of the world’s thriving cocaine business: enterprising black-market businessmen like Escobar, who had grown up in the Medellín suburb of Envigado, saw in marijuana, and then cocaine—derived from coca grown in neighboring Peru and Bolivia—an opportunity to reap profits beyond their wildest dreams. That opportunity lay in processing and shipping the drugs to US shores. By the early 1980s, Escobar, along with Gonzalo Rodríguez Gacha and the brothers Jorge Luis, Juan David, and Fabio Ochoa Vásquez, had formed a powerful narco-trafficking syndicate, commonly known as the Medellín cartel, which at its peak some sources estimated to have supplied as much as 80 percent of the global cocaine market, bringing in billions of dollars a year. When Forbes magazine published its first list of world billionaires in 1987, both Escobar and Jorge Luis Ochoa made the list. Escobar stayed on it for another seven years.

From the start, the cartel used savage means to achieve its goals: torturing and executing competitors or opponents, threatening or bribing officials to achieve its aims. Colombia’s government was slow to take action against the drug business—in the 1970s and early 1980s there was even some debate, led by a prominent politician (and future president), Ernesto Samper, about legalizing drugs. Samper pointed out that the drug business was rapidly becoming too powerful for the state to control, and that they needed to find an alternate way of regulating it: “We are, at the end of the day, faced with a choice of either recognizing and redirecting the mafias, or having them… take us all down the wrong path.”

Meanwhile, Escobar, who came from the middle class and aspired to a sort of legitimacy among the country’s elites, had built up some popular support by pouring money into public works, including the construction of an entire neighborhood for low-income residents of Medellín, as well as multiple soccer fields across the city. While some of Medellín’s traditional circles of power shunned the new-money drug lords, others quickly attached themselves to their wealth. Escobar became famous for his supermodel lovers and his extravagant spending on parties, cars, and the personal zoo full of wild animals that he kept on his lavish property, the Hacienda Nápoles. In 1982, he even won a seat as an alternate (a substitute, in the event the primary office holder could not perform his duties) to a member of the Colombian Congress.

But in the mid-1980s, the administration of Ronald Reagan in the United States, which was ramping up its own war on drugs, increased the pressure on Colombia’s government to take legal action against the drug lord. President Belisario Betancur named Rodrigo Lara, a strong critic of the Medellín cartel, minister of justice, and the Colombian Congress began to debate an extradition treaty with US officials that would allow the government to send narco-traffickers like Escobar to the United States for trial. Then, in March 1984, in a joint operation, the Colombian national police and the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) raided Tranquilandia, a vast cocaine-processing complex hiding in the jungle plains of the eastern Colombian states of Caquetá and Meta, run by the Medellín cartel.

Escobar reacted furiously, unleashing a wave of terror in Medellín and in other cities that had escaped earlier bouts of large-scale violence in Colombia mostly unscathed. Within a month, assassins sent by the cartel had murdered Lara. Over the following years, murders—including assassinations of high-profile officials—would become commonplace. In 1986, assassins murdered Colonel Jaime Ramírez Gómez, the antinarcotics police chief who had led the raid on Tranquilandia. Escobar was believed to have ordered the 1989 assassination during a political rally of popular Liberal presidential candidate Luis Carlos Galán, an anticorruption crusader and critic of the cartels, who supported the extradition treaty with the United States. Shortly afterward, Escobar ordered the planting of a bomb on a domestic passenger airplane on which he believed Galán’s replacement, César Gaviria, would be flying. Gaviria wasn’t on board, and went on to become president. But more than one hundred people died when the jet exploded five minutes after taking off from Bogotá.

Hospitals in Medellín became dangerous places to go, as shooting victims who made it that far often had assassins on their heels—teenagers on motorcycles, gang members, or simply killers for hire. Many of the assassins would themselves die before ever becoming adults. Often, the sun would rise to find the city littered with human bodies, many of them never to be identified. Various criminal gangs and armed factions silently battled for control of the city and its profitable cocaine markets. With his seemingly limitless resources, Escobar gave public officials a choice between plata o plomo—silver or lead, meaning a bribe or death by a bullet. It became nearly impossible to tell who was with Escobar and who was against him. Meanwhile, the Colombian military and police engaged in their own acts of brutality, killing and “disappearing” young people believed to be Escobar’s associates.

By 1991, when Velásquez became inspector general of Medellín, Escobar had agreed to a policy of “submission”—he turned himself in to the authorities, but on the condition that he would not be extradited to the United States and would stay at La Catedral, a “prison” he had built for himself on the top of a mountain with a view of all of Medellín. But the killings continued: the drug kingpin kept running his criminal operations from La Catedral, and at that point, he was conducting a war not only against the government, but also against the rival Cali cartel, run by the brothers Gilberto and Miguel Rodríguez Orejuela. And in his efforts to maintain ever tighter control over the cartel and its profits, he had alienated some of his closest associates.

AS INSPECTOR GENERAL, the thirty-six-year-old Velásquez took his job seriously, and in one of his early investigations uncovered a torture chamber that he believed was being used by members of an elite joint anti-kidnapping squad operated by the army and police known as UNASE (Unidad Anti-Secuestro y Extorsion, or Anti-Kidnapping and Extortion Unit). His work angered sectors of the public security forces, but at the same time, Velásquez had to constantly worry about an attack from Escobar’s people: on one of his first days on the job, a former colleague had introduced him to two nicely dressed men who, claiming to be emissaries from Escobar, had offered him a suitcase full of tens of thousands of dollars, “in appreciation” for his work on behalf of the people of Medellín. Velásquez had rejected the money, insisting that his salary was paid by the government. But, concerned that Escobar would seek revenge, he had then visited the drug lord at La Catedral, to explain in person why he would not accept money from him. Fortunately, the sweaty Escobar, who was in the middle of a game of soccer when Velásquez arrived, had seemed to be in an amiable mood at the time. Far from being the scary, aggressive figure Velásquez had always imagined, Escobar acted surprisingly submissive, with his head bent down, staring at his feet as they moved pebbles around on the ground. Only occasionally did he look up at Velásquez, with an expression of something akin to shyness. Velásquez never was able to figure out why Escobar acted that way—it was not as though he had much power to intimidate the drug lord. Velásquez immediately explained what had happened with Escobar’s envoys, and that he could not accept money. Escobar listened, and apologetically told him not to worry: it was too bad that there had been a mistake, but he wasn’t seeking anything in exchange, he said. He simply wanted to recognize the good work Velásquez was doing. Velásquez repeated that he would not take money from anyone, as he was simply doing his job, and Escobar seemed to take it in stride. With that, Velásquez left, feeling a surge of relief: it looked like the drug lord was leaving him alone—at least for now.

Velásquez would go to La Catedral two more times. In early 1992, his boss in Bogotá, Carlos Gustavo Arrieta, the national inspector general, ordered him to conduct an inspection of the inside of the prison. There were concerns about the prison’s security and the illegal activity possibly taking place inside. Few public officials had ventured inside La Catedral, but Velásquez got to meet Escobar again. He took photos of what he discovered was a luxurious, well-furnished house with a gym, kitchen, and several bedrooms. It was filled with expensive televisions, pool tables, and elegantly carved, heavy wooden furniture, all of which a prisoner was not supposed to have. There was even a large doll’s house for Escobar’s young daughter, Manuela, to play with when she visited. It would have been impossible for all that to get into La Catedral without National Prison Institute officials noticing. The photos were eventually made public, generating a national outcry over the government’s permissiveness, but as far as Velásquez could tell, the government did little to change the status quo.

In July 1992, Velásquez received instructions to go to La Catedral again, though he was not told why. A few weeks earlier, Escobar had killed two of his associates, Fernando Galeano and Kiko Moncada, and had their bodies dismembered and incinerated on the grounds of La Catedral itself. That was the last straw for the government of César Gaviria, which then decided—according to official accounts—to transfer Escobar to another prison. But the operation was poorly coordinated. When Velásquez arrived outside the inner perimeter of the prison in the late afternoon, he encountered a stout but tough-looking army general, Gustavo Pardo Ariza, who was having an animated discussion with the young, polished vice minister of justice, Eduardo Mendoza, and the national prisons director, Colonel Hernando Navas. Mendoza and Navas, who had flown in from Bogotá, were arguing that they should go inside to explain the transfer to Escobar. Pardo Ariza opposed the idea, but upon their continued insistence, suggested that Velásquez join them. To Velásquez, it seemed odd that they disagreed: Why didn’t Mendoza and Navas want witnesses to whatever they were going to say? Navas then said that he should go in alone. After much back and forth, Pardo eventually relented. Navas went in, and, after a while, Mendoza was called in as well. Velásquez waited outside for a couple of hours. At one point, a guard came up to the fence and summoned Velásquez: Navas and Mendoza wanted him to join them, he said. Velásquez was uneasy, but got ready to go in, when Pardo stopped him—things didn’t look right. He instructed the guard to tell Escobar that nobody else was going in until he knew that Mendoza and Navas were safe. Well into the evening, they learned that Escobar was claiming he had taken Mendoza and Navas hostage. He was reportedly furious: he believed the transfer was really an effort to extradite him.

Velásquez spent the rest of the night sitting on a small chair in a shack outside the prison, with only his suit to protect him from the dark mountain chill, as he and the army general waited for a breakthrough. At one point, he jumped when an airplane flew low overhead and all the lights went off in the prison. Finally, at dawn, as if in a dream, Velásquez glimpsed heavily armed soldiers materializing through the fog and trees, encircling La Catedral. He heard an explosion and shouts. Bullets whizzed by him, in both directions, and he ran out of the exposed shack to hide behind a tree. By 9 a.m., the news was out: special forces had seized the prison. Escobar was gone.

Meanwhile, María Victoria had spent the whole night without news from Velásquez. She had told the kids that everything was fine, but she was worried sick. Had he been killed? Abducted? The news reports about the seizure of the prison did not mention him. So when morning came, she dropped the kids off at school and drove to Envigado, the hometown of Escobar, to try to talk to Mayor Jorge Mesa, who was rumored to be close to the drug kingpin. By sheer force of will, she got Mesa’s guards to let her in. Mesa was initially unfriendly, but eventually made a phone call. He then told her: “Your husband was a coward who didn’t want to go in and talk to Escobar. I recommend that you hide your children immediately. You don’t know who Pablo is when he’s mad.” Velásquez was alive, he said, but he reiterated that Escobar was angry, and their children would pay the price. Relieved to hear her husband was alive, María Victoria thanked him and rushed to the pay phone to call her sister, asking her to pick up the children from school right away and hide them.

While María Victoria was in Envigado, Velásquez had completed an inspection—required by his position—of what had happened at La Catedral after special forces entered, and had come back to Medellín. But he was almost immediately pulled into a meeting at the office of Juan Pablo Gómez Martínez, the governor of Antioquia. In the middle of the meeting, a phone call came in from Escobar’s brother, Roberto, who was also known as “El Osito” (The Little Bear). The person with whom Velásquez was meeting turned on the speaker-phone: El Osito was railing against Velásquez, saying Pablo Escobar viewed Velásquez as part of a plot against him. “He has to pay, he knew what was going to happen,” Velásquez later recalled El Osito saying. That night, Velásquez appeared on local news shows, explaining what had happened from his perspective: he had been sent to La Catedral with no information about what was going to happen, and had not been involved in any of the planning about the transfer. Some of Escobar’s associates later told him that the interview had saved his life—it had corrected their impression that Velásquez had been planning to trick Escobar into being extradited to the United States.

María Victoria Velásquez, Medellín, 1980s. © Iván and María Victoria Velásquez.

The family was finally reunited that night. María Victoria later recalled that Velásquez was so stressed and tired that his hands were shaking as he lit one cigarette after another.

Escobar’s escape marked the beginning of a long period of constant fear for Velásquez and his family, not only because of Escobar’s threats, but also because of what Escobar’s enemies might do. Now that Escobar was on the run, he had escalated his attacks on the government and his enemies in the drug world. At the same time, an elite Colombian police unit, the Bloque de Búsqueda, or Search Bloc, focused on finding Escobar; it worked closely with a US special forces team known as Centra Spike, which fed intelligence to the Colombians. There were also rumors of the involvement of a group of former associates of Escobar who had turned against him. Known as Los Pepes (for Persecuted by Pablo Escobar, or Perseguidos por Pablo Escobar), the group was said to be torturing, kidnapping, and killing Escobar’s cronies, weakening his influence. A few of Escobar’s associates had turned themselves in to the government through Velásquez’s office, which they viewed as safe—unlike the police, who might call in Los Pepes. At one point, Velásquez even sent officials to accompany Escobar’s family on a drive from the airport to their apartment in Medellín, as they feared an attack by Los Pepes. After all, “the fact that he was a killer did not mean that we had to tolerate other killers murdering his family,” recalled Velásquez. But all these actions meant that the members of Los Pepes might view Velásquez himself as an enemy. For months, the Velásquez family lived with a heavy military guard. For the first, but not last, time, María Victoria started receiving threatening phone calls at work, though she kept them to herself so as not to upset her husband. They kept the kids in their apartment—not even letting them go to the door of the apartment complex, much less to the park or to friends’ parties. Her parents tried to keep what was happening from her, but Catalina, who was then twelve, could sense the tension, and she had recurrent nightmares about something happening to her father.

The tense atmosphere came to an abrupt end on December 2, 1993, when the government announced that a squad from the Search Bloc had located Escobar in a Medellín house and shot him to death as he tried to escape through the roof. US and Colombian officials celebrated the killing as a landmark success in the war on drugs, and many people in Medellín breathed a sigh of relief: with Escobar’s killing spree over, maybe now they would enter a time of renewed peace.

For a while, as the slaughter slowed, that seemed to be the case. Few people understood that Escobar’s slaughter had planted the seeds for yet another brand of terror.

BY THE TIME Velásquez came back to Medellín four years later, he was forty-two years old. Tall and gaunt, with large brown eyes set in a pale face, straight brown hair that crept over his ears, and a strong, slightly curved nose above a thick mustache, he usually projected a thoughtful calmness that only broke when he smiled or laughed, making his whole face light up. He could be very affectionate with his kids, but that would have surprised most people, as he usually came across as distant and formal with colleagues. His everyday attire was formal, too, though simple, consisting mainly of suits and sweaters in solid grays or earth tones; he didn’t spend much time or money on his appearance. Only his smoking habit hinted at the stress he sometimes felt.

Velásquez had left his job as inspector general of Medellín in 1994, when a new national inspector general took over. For the next four years he had served as a representative of the inspector general’s office before an administrative tribunal in Antioquia, and then, in Bogotá, as an assistant justice for the Council of State, one of Colombia’s four high courts, which also focused on administrative matters. These jobs kept Velásquez busy, so he had little time to stay on top of how the war was evolving in Antioquia beyond what appeared in the news media.

It was only when he took over as chief prosecutor in 1997 that Velásquez started to grasp the nature of the new threat facing the region: the newly organized, seemingly very well-funded paramilitary groups that were swiftly taking over the countryside. They were especially active in two of the states he was covering: Córdoba and Antioquia. Certainly, paramilitaries had been killing activists for years, but these groups seemed much larger, more brazen, and even more bloodthirsty than the death squads of the past. His bosses in Bogotá, Attorney General Alfonso Gómez Méndez and Deputy Attorney General Jaime Córdoba, had urged him to make investigating the paramilitaries a priority, but they had warned him that it would not be easy. Two criminal investigators from his office had been killed, apparently by paramilitaries, earlier that year, and there were reports that paramilitaries had infiltrated the CTI (Cuerpo Técnico de Investigación, or Technical Investigation Team, a branch of the attorney general’s office that conducted criminal investigations).

Worse yet, if Velásquez’s old friend Jesús María Valle was to be believed, the military was actively backing the paramilitaries. In the preceding months, Velásquez had watched Valle embark on a one-man crusade to draw attention to what he viewed as complicity between the military and the paramilitaries.

VELÁSQUEZ HAD KNOWN Valle since the mid-1980s, when his law school thesis adviser, J. Guillermo Escobar, had invited him to join an informal group of lawyers calling themselves the Group for Prisoners’ Human Rights. Velásquez had married and begun having children in his twenties, and had invested most of his energy in those years in working and supporting his family while María Victoria went to law school. But Velásquez had always had a quiet but deep passion for issues of social justice, so when J. Guillermo called, Velásquez jumped at the opportunity to join the group.

The group organized prison visits to talk to inmates, found them legal representation, and checked on their prison conditions. In doing so, they found one prison where inmates who “misbehaved” were locked up in a narrow, windowless corridor known as the “tunnel.” There, they had to scurry, lest they get drenched in waste from other prisoners on the floors above, which poured down from openings in the ceiling. In another prison, inmates were punished by being locked up together in six-by-six-foot cells, ten prisoners to a cell, with no toilet and only a bottle they passed around to take care of their physical needs. Through letters, complaints, and public statements, the Group for Prisoners’ Human Rights protested the conditions, and sometimes they managed to get institutions to change the rules.

Members of the group, including Valle and Velásquez, would regularly meet at each other’s homes. Over cups of bitter coffee (or, in J. Guillermo’s case, endless glasses of Coca-Cola), often smoking, they would stay long into the night talking about politics, law, and current events. It was a thrill to Velásquez: here was a community of people like him, who believed—all evidence to the contrary—that a more just society in Colombia was possible. Not only that, but they were doing something about it.

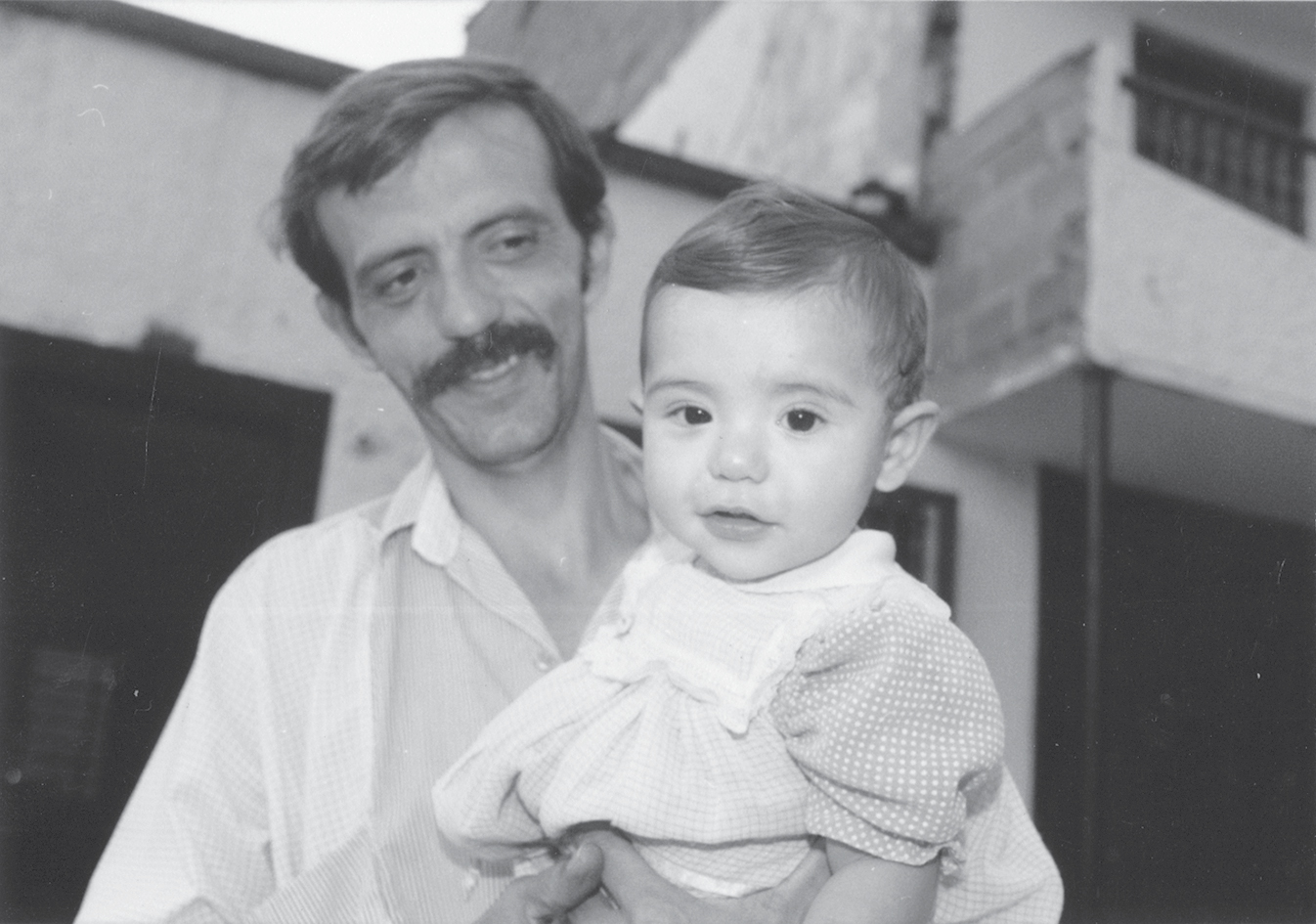

Iván Velásquez and his daughter Laura, 1988 or 1989. © Iván and María Victoria Velásquez.

Velásquez enjoyed Valle’s lively storytelling style and the expansive smile under his thick, dark brows. The two men had a lot in common beyond their idealism. Both Valle and Velásquez had grown up poor, the children of deeply Catholic, politically conservative parents, and both had worked their way through law school at the University of Antioquia, though a few years apart.

The two also had differences: by the time they met, Valle, as part of the Permanent Human Rights Committee of Antioquia, was an outspoken activist on behalf of various social justice causes in Medellín. By contrast, although Velásquez was friendly with several of the committee’s members, and was deeply shaken by the murders of so many of its leaders in the mid-1980s, he never seriously considered joining it. In his mind, he was simply a lawyer who did what he could to improve the system—not an activist. Still, in 1989, Valle convinced Velásquez to replace him as head of the Antioquia Bar Association, and with that platform, Velásquez regularly organized groups of lawyers to raise issues of public concern with the authorities. When, in 1990, the Colombian government held elections for a constituent assembly—a group of people to draft a new constitution for Colombia—Velásquez, Valle, J. Guillermo Escobar, and a few other friends ran together for seats. Flyers promoting their candidacy described them as representing “the damaged justice system, the massacred youth, [and] those who have been tortured,” and, most importantly, it said, “WE ARE HUMAN RIGHTS.”

They did not get elected, but it was an exciting experience. Velásquez began thinking more about public service through government, which may have influenced his eventual decision to take the inspector general job in 1991. He had refused the job at first, but María Victoria had teased him relentlessly: “Ay mijo” (“Oh my boy”), she said in her sassy style, “aren’t you the one who’s always going on about people’s rights? And now that you have a chance to do something about it, you say no? I guess it was all just talk after all… oh well.” Valle had also encouraged him: Velásquez was perfect for the job, and it would make a world of difference to have someone trustworthy there. Eventually, Velásquez agreed: “I guess I’m stuck: either I look like a hypocrite, or I have to not only take the job, but also do something with it.”

But as much as he liked and trusted Valle, when Velásquez returned to Medellín after two years away, he was not quite sure what to make of his friend’s accusations about paramilitaries and their links to the military. He was particularly surprised and concerned by the tension between Valle and Governor Uribe, whom Velásquez knew a bit and had once even admired.

A SLIGHT MAN in his mid-thirties, with perfectly combed and parted hair and a Boy Scout’s look about him, Álvaro Uribe seemed like a different kind of politician from those of Colombia’s past: he had gained notoriety in 1985 when, along with his second cousin Mario Uribe, he had founded a dissident faction of the Liberal Party known as the “democratic sector” of liberalism in Antioquia, rebelling against the traditional patronage system by which the party was run in the state. In those days, it was common for politicians to dole out gifts, promise jobs, or serve alcohol at political events, to encourage voters to vote for them. Senior party officials, rather than voters, decided who would get to run for office or hold positions in government. Uribe, however, refused to engage in patronage; instead, he devoted himself to traveling widely within the state, talking directly to voters, and trying to understand their concerns and address their problems head-on. He developed a reputation as a workaholic. When he took over the governorship, the US embassy in Colombia described him in a cable as “a bright star in the Liberal Party firmament.”

Like Valle and Velásquez, Uribe had studied law at the University of Antioquia, though Uribe was finishing his studies around the same time that Velásquez was starting his, in 1975. Uribe had been a good student when he attended in the early 1970s, but he had also become deeply involved in the school’s politics, constantly speaking out against protests by an alphabet soup of leftist or anarchist student movements—JUPA, MOIR, IRI, GUB, as well as the ELN—whose protests often led to classes being canceled. María Victoria, Velásquez’s wife, who was a student there in the late 1970s, recalled that for a time, there were people at the university “burning many cars, throwing stones, and things like that.” “One day,” she said, “they burned a car with a nun inside, and even though they tried to open the doors, they were unable to do so. After that, there was a general repudiation. But throughout that time it was more or less the same story: a lot of noise without much structure.” A former classmate of Uribe’s recalled thinking that, given what he viewed as Uribe’s right-wing positions, it was strange that Uribe was attending the university. Uribe surrounded himself with a small group of students with similar views, and he routinely stood up in the middle of protests to object. It was a gutsy and unpopular thing to do, but it earned Uribe a reputation early on for speaking his mind, regardless of the consequences.

Uribe had grown up in relative comfort between Medellín and the small Antioquia town of Salgar a few hours away, where his family owned land. His father was extremely charismatic—a “snake charmer,” as one of Uribe’s friends put it—but also a demanding rancher who loved horses, parties, and women. Despite some accounts saying that the family was wealthy, people close to Uribe say that his father bought and sold a lot of land, and was a risk-taker, so his wealth fluctuated a great deal. This might explain Uribe’s attendance at the University of Antioquia, a public school. Uribe’s mother was said to have been a strong figure, deeply involved in the women’s suffrage movement, who taught Uribe to recite poetry from Pablo Neruda, as well as speeches by Jorge Eliecer Gaitán and Simón Bolívar, and encouraged his political aspirations. His parents separated in 1964, when Uribe and his four younger siblings were small—by some accounts, the separation was traumatic for the children, especially because marriage break-ups were highly unusual and viewed as shameful in their conservative society. But Uribe seems to have remained close to both his parents, and several people close to him say that he inherited his father’s authoritative temperament, if not the more jovial aspects of his character. Instead, the younger Uribe had acted, since he was very small, as a man with a mission. Friends, relatives, and former teachers remembered that even as a small child, Uribe wanted to be president of Colombia—not out of personal ambition, but because he was utterly committed to the country. One colleague recalled Uribe saying, in the mid-1980s, “I would like, at the end of my days, to look back upon my life and see that I have spent it in the service of the nation.”

Immediately after finishing law school, Uribe landed a senior management job in Empresas Públicas de Medellín (Medellín Public Enterprises), the city’s public utilities company. It was the first in a string of increasingly high-profile public positions he held, which included, in the early 1980s, serving as director of the national civil aviation agency charged with overseeing and regulating all civilian air travel in the country. He also served a brief stint as mayor of Medellín.

Despite his advantages, Uribe had also been scarred by Colombia’s conflict. Years later, in his autobiography, he would recount a memory from childhood that mirrored Valle’s own experience during La Violencia: One afternoon, when he was five or six, more than three hundred Liberal Party fighters arrived at his family’s farm demanding food and refuge. “I remember watching as my mother… cooked meals for this gang of men,” he wrote. “I remember watching as my father… talked with these outlaws with guns. And I remember yearning, at the purest, most primal level, to live in a Colombia where armed men would never invade our farm, where my family would all be safe, and where no one would ever have to lock herself inside her home, staring at the door in terror.”

On June 14, 1983, Uribe’s father, Alberto, was killed by the FARC on one of his ranches, Guacharacas, where Uribe recalls that the family employed forty workers and a butler. His father, Uribe later said, had resisted many extortion attempts by the FARC, and had become increasingly worried about security on the ranch. The day his father was killed, Uribe’s brother Santiago and sister María Isabel were at the ranch with him and several of the workers when a group of FARC members showed up and attempted to kidnap him. He resisted, shooting at them, but the FARC shot him twice, killing him before running away. Santiago was wounded but managed to flee. In his autobiography, years later, Uribe would write eloquently about the terror that the FARC had inflicted on so many Colombians. But, he stressed, he did not believe in revenge. Instead, he wanted to wrest the country back from lawlessness. “The final stage of all this grief,” Uribe wrote, “was not hatred but love: love for my country; love for my countrymen; and love, above all, for a future Colombia where fathers would not be torn away from their daughters and sons.”

Velásquez’s first impressions of Uribe were very positive. He liked Uribe’s stance against corruption and patronage in the Liberal Party. Uribe was young and democratic, and he seemed like a different, more honest type of politician. María Victoria did not share Velásquez’s admiration: “Uribe said he exited [liberalism] because of corruption. Iván believed him. He thought that that was a dignified, brave position, and that all political movements needed to have people like Uribe, that he was the model to follow.” Many other Medellín residents seemed to agree with Velásquez. But something about Uribe always rubbed María Victoria the wrong way: yes, he was attractive, educated, and sounded good, but his break with the Liberal Party somehow struck her as selfish and ungrateful. That was more of a gut reaction, though, and Velásquez did not share it.

Velásquez recalled first meeting Uribe in person at a security summit held by the mayor of Medellín in the months after Escobar’s escape from his prison-mansion of La Catedral. The war between Escobar’s people and his enemies was in full swing, with bombs going off or killings happening every day. Uribe, then a senator, was seated next to Velásquez, who was inspector general of Medellín, and leaned over to ask whether there was any way to get Escobar to turn himself in. Velásquez pointed out that the difficulty was that the security forces were under orders to shoot Escobar; Uribe replied that he could bring together all the Antioquia members of congress to surround Escobar while he turned himself in, and in that way ensure his safety. Velásquez agreed that it was worth a try. He approached former Antioquia governor Álvaro Villegas, who lived in the same building as Escobar’s mother-in-law and agreed to help. Through Escobar’s wife, the three men sent the message to the drug lord. A few days later, on December 26, 1992, Escobar wrote a letter to the government offering to turn himself in, though insisting on extreme conditions—all the members of the Police Investigations Unit had to be fired—and making new threats of violence. The letter, which concluded with a note thanking Velásquez, Uribe, and Villegas for their “goodwill,” was leaked to the press, and Los Pepes responded swiftly, setting off multiple bombs on or near properties belonging to Escobar’s relatives. One of the bombs went off near Villegas’s own house, and he was badly injured. The leak of the letter—which, in any case, President Gaviria rejected—and the bombings by Los Pepes derailed the three men’s efforts. Escobar would be dead within the year.

Velásquez and Uribe did not stay in touch, but Velásquez continued to view Uribe as a serious, committed, and generally progressive man, even if they didn’t agree on everything. Since becoming governor, however, Uribe seemed to have taken a turn toward the right, becoming much more militaristic and aggressive in his approach to security in the region, and particularly to fighting the FARC guerrillas. Velásquez was particularly concerned about a program the national government had authorized by decree a few years before, in 1994. The decree allowed groups of people in “high-risk” areas, where the military might have trouble providing support, to apply for licenses to provide private security services in those regions. The decree also authorized the groups, known as “Convivirs” (for Cooperativas de Vigilancia y Seguridad Privada, which means Private Cooperatives for Vigilance and Security), to use weapons that would normally be restricted to the military and law enforcement. In theory, the groups would not engage in combat, but rather would serve as a sort of “watch committee.” They were to be in regular contact with the authorities, reporting suspicious activity.

The decree allowing the Convivir program had been controversial from the start. Some officials were afraid that it would simply create a new way for the military to legally establish paramilitary groups. In the 1960s and 1970s, the Colombian government had passed decrees and laws allowing the Colombian military to arm civilians to establish self-defense forces, supposedly to defend themselves from the guerrillas. But a number of those groups, in the 1970s and 1980s, had become powerful criminal enterprises, especially in the Middle Magdalena region along the Magdalena River and in the town of Puerto Boyacá, where they had begun committing heinous murders and massacres with military support. By the mid-1980s, the paramilitary group known as the Association of Middle Magdalena Ranchers and Farmers (Asociación Campesina de Ganaderos y Agricultores del Magdalena Medio, or ACDEGAM) was also working closely with drug traffickers—Gonzalo Rodríguez Gacha, aka “The Mexican,” a powerful member of the Medellín cartel, underwrote them. In the midst of the bloodshed of the late 1980s, Colombia’s government had passed new laws criminalizing the establishment of groups of assassins or death squads and suspended decree provisions that had allowed the military to arm civilians. But the 1994 decree, and regulations issued by President Ernesto Samper’s administration allowing the establishment of the Convivirs, had created a new opening for government support of “self-defense” groups—and Governor Uribe enthusiastically embraced them.

In a later interview, former president Samper would say that he had viewed the Convivirs as “a space in which citizens could organize their own defense in a peaceful manner, but [Uribe] began to use them as an instrument of war, blindly defending them.” Dozens of Convivirs sprouted up throughout Antioquia, with strong support from the governor, who portrayed the Convivir program as a harmless and legitimate way for civilians to cooperate with the military to further peace. Uribe’s chief of staff, Pedro Juan Moreno, a businessman on the far right known for his quick temper and tendency to use harsh language and insult people, regularly held meetings with Convivir leaders and Fourth Brigade members to coordinate the provision of security and intelligence in the region. By 1997, according to one estimate, there were about 414 Convivir groups operating throughout the country with more than 120,000 members. Seventy-eight of those groups were in Antioquia.

The media, human rights organizations, and even the United Nations became increasingly critical of the Convivirs, especially in 1997. Samper’s original decree had raised concerns about the risk the government was taking, if it was seen as supporting death squads, but Uribe’s aggressive implementation of the program was, in the eyes of many, confirmation of their worst fears, particularly as reports began to surface of Convivir members becoming involved in criminal activity. Uribe brushed off their concerns. “People imagine that the Convivirs are private, armed armies,” he said to one news outlet in November 1997. “If only they knew how they operate in Antioquia.… [T]heir experience has shown the people of Antioquia that what’s really needed is solidarity, in working jointly with public security forces and providing timely information.” Convivir members who committed crimes should be brought to justice, he argued, but that didn’t mean the whole program was flawed.

Uribe’s backing for the Convivirs generated a great deal of criticism, but it also garnered him support in much of Antioquia—including from Velásquez’s father. In arguments, Alberto Velásquez, who looked like an older, white-haired and blue-eyed version of Velásquez, kept going back to the same position, one that was reflected in some local papers and had become the talking points of some politicians: The country needed to find a way to strengthen security in the countryside. It was simply intolerable for farmers, landowners, and businesses to be constantly subject to the FARC’s threats, extortion, and kidnapping. Lands were being lost, businesses shutting down. The highways were becoming so dangerous—because any minute you could be stopped by a FARC patrol and taken for ransom—that many people were choosing to give up travel entirely. For God’s sake, the FARC were in Medellín itself, hiding out in plain sight, dressed as civilians. What was so wrong with the government supporting citizens who were simply trying to defend themselves? Something had to give!

Velásquez would sigh, getting increasingly irritated. He knew his father was exceedingly proud of him, and he had picked up a lot of his father’s attitudes: the value of reading, hard work, and study; his disgust with officials who took bribes and broke the public’s trust; his belief that, even when they were flawed, it was more important to try to make institutions of government work than to tear them down. But they parted ways on most policy matters. His father was so attached to protecting what he viewed as the country’s established institutions (the Catholic Church, the military, business), and maintaining—or imposing—order, that he often ended up taking radical positions that Velásquez found appalling. For example, his father was still a great admirer of Laureano Gómez, a highly controversial figure who had led Colombia’s Conservative Party from the 1930s to the 1960s, and who was known to sympathize with fascist governments, like Hitler’s in Germany and Franco’s in Spain.

In Velásquez’s view, it was one thing to say the government had to protect its people and fight the guerrillas. It was something else entirely to let the military hand out military-grade weapons to civilians and get them directly involved in the conflict. And he agreed with many in the human rights community that the Convivirs could easily be used as cover for paramilitary groups.

Some, like Valle, even spoke interchangeably of the paramilitaries and the Convivirs, as though they were the same thing. In an August 25, 1997, speech commemorating the ten-year anniversary of the murder of Valle’s predecessor, Héctor Abad, Valle described how he saw the situation in small towns across Antioquia:

Dark forces appeared that replaced the mayor.… [T]hey were paramilitaries, Convivirs, self-defense forces. And the concept of public authority became ambiguous: people became friends or enemies of the Convivir, friends or enemies of the paramilitaries, friends or enemies of the guerrillas.… Today I can say that the meridian of violence courses through Antioquia. We are exporting, through a mistaken conception of public order, violence to other peaceful states… [and] to the whole country. And the paramilitaries and the Convivir[s] are confused in their uniforms, their headquarters, the vehicles they use.… I have seen it with my eyes, I have witnessed it with the people of my land, my towns.… Those people I saw born, those people with whom I heard the whistle of misery in the mountains, have been killed. And I have gone everywhere invoking the rights… of the peasants, and I haven’t received a positive answer.

Velásquez took Valle’s comments seriously. But he had yet to grasp their full implications.

AS MARÍA VICTORIA drove the car up the Las Palmas highway, climbing the tall, densely forested mountains embracing Medellín, on that Saturday in late October 1997, the brakes gave out. “Stop,” the normally serene Velásquez said, growing alarmed. But she couldn’t stop, and the vehicle kept powering farther up the slope. If they continued, they’d soon be driving alongside a cliff.

But then Velásquez spotted a side street. María Victoria swerved onto it. “We’re going to die,” María Victoria thought, as she lost control of the car, hurtling down the steep incline. They turned upside-down as the car rolled, until finally it stopped, smashing against a wall.

“Is everyone okay?” Velásquez and María Victoria breathlessly asked, turning to each other and their children in the back. Catalina had a deep gash in her leg, and Laura was in pain: they’d later learn that one of her kidneys was bruised.

To this day, María Victoria grows enraged as she tells the story: “First they give him a car without brakes, then they tell him that he doesn’t have a right to a driver [on Saturdays], and when we call the traffic police, people from the office beg us not to report that I was driving or that they had given us the car that way. Because there was, in fact, a driver for us to use.”

It was evident to her that someone in Velásquez’s office had sabotaged the car and deliberately arranged things so that Velásquez or his wife would be driving the car on Saturday. Someone wanted him dead.

Velásquez wasn’t so sure about that. In any case, ever since his days as inspector general, his view had been that there was no point in worrying about security. In Colombia, if someone really wanted to kill you, they would.