CHAPTER 6

IN PLAIN SIGHT

WERE IT NOT FOR ITS history, the Padilla parking lot would be entirely unremarkable. A small neon sign on Tenerife Street in downtown Medellín announces “Parqueadero Padilla” in cursive script above the entrance to a paved lot with space for thirty or so cars, some of them partly covered, others in the sun. Much more memorable is the hectic commercial neighborhood—known as “El Hueco,” or The Hole—surrounding the parking lot. Padilla is squeezed in among what feels like an endless stream of small businesses, selling anything you might need to build or furnish a house. Sinks, lengths of fabric, foam for mattresses, cement, ceramic tiles, doorknobs, hooks, tools, scraps of metal, are piled high, hanging from walls and doors and pouring out of the little warehouses that sold them. Every so often, the flow of stores is interrupted by an old barbershop, or a little restaurant serving coffee and a set and affordable “menu of the day” (usually your choice of meat or fish, juice, soup, and maybe some french fries or rice, plus a small dessert) for lunch.

Shoppers mill about, but there are also many men—ordinary men, in jeans and polo shirts—standing idly near stores, looking sharply at everything around them, staring at passersby. El Hueco is said to be one of the safest parts of the city, but according to some, that’s because it is paramilitary territory. The men who stand around watching are lookouts, guarding the area and reporting back to their bosses if they notice anything unusual.

The Padilla parking lot, and its street, looked much the same when the CTI searched it on April 30, 1998.

Diego Arcila, the CTI agent who was a former seminarian, had picked up the address of the parking lot and one other location on the wiretap, but Oviedo had decided to hold off on searching it at first. He was still concerned that if they moved too quickly, the paramilitaries would realize that the CTI was listening to their calls.

Their plan that morning had simply been to stop and search a truck. Arcila had heard on the wiretap that the paramilitaries were planning to move some cargo that day on the road from Medellín to the Western Antioquia town of Sopetrán.

Sergio Parra and a few other CTI agents intercepted the truck on the road and pulled it over, pretending it was a routine search. And, sure enough, when they looked in the back, they found it was stuffed with what would turn out to be 150 military uniforms that, they surmised, were meant to supply the paramilitaries operating in Western Antioquia. They also found two beepers, ten .38-caliber weapons, and, under the driver’s seat, US$20,000.

But the surprise came when they checked the names of the driver and two passengers. One of the men, a retired army officer, was, according to Arcila’s analysis of the wiretap information, the paramilitaries’ operational head for all of Antioquia.

It was a big blow—bigger than they had expected. And since the CTI, rather than the police, was conducting the arrests, Oviedo concluded, the paramilitaries would probably figure out quickly that the CTI was monitoring them. It was time to search the two Medellín addresses the paramilitaries had mentioned in their calls. To be safe, Oviedo instructed a massive number of agents to accompany them—as many as 120, as Oviedo later recalled it.

The first address they went to turned out to be a dead end: an ordinary diner. And when they first arrived at the second address, the Padilla parking lot, it looked like it, too, would prove to be nothing. It was just a small parking lot with cars in it.

But the investigators decided to walk around it anyway, and on the grounds they found a cheaply built two-story shack. They knocked on the door—nothing. They tried again, and still, nobody answered. Yet they could hear movement inside. Oviedo asked one of the CTI agents, a very large man, to kick in the door. And in they went.

Inside, they found two young women and a broad-faced man in his early thirties carrying a backpack. They all looked flustered, and Oviedo told them to wait while the investigators searched the space. He noticed a radio-telephone on a table in the main room and guessed that they used it to communicate with their commanders.

“Can I leave now?” asked the man with the backpack, getting impatient. “No,” said Oviedo, “you wait here.” In searching the space, the agents noticed that one piece of furniture, an armoire, looked like it had a fake backing. They pulled it off and found two detailed accounting books, carefully kept, detailing records from 1994 to 1998. In another piece of furniture they found a pile of propaganda material for the paramilitaries, a map of the organizational structure of the ACCU, and various other ACCU documents. They also found a laptop and a desktop computer, a couple of cellphones, and dozens of floppy disks sitting next to a shredder. Someone had managed to shred one of the disks, but clearly they hadn’t had the time to finish.

When they finally searched the man’s backpack, they found a Beretta pistol and two cartridges as well as a weapons license in the name of Jacinto Alberto Soto—the man’s name—from the Fourth Brigade. They also found three checks in different names worth about 13 million pesos (around US$10,000 at the time).

The investigators put Soto and the two women under arrest and arranged to take all the materials to their offices.

AS THEY WRAPPED up the search, the normally affable Sergio Parra, who had joined the group during the search, looked worried. Oviedo would later recall that the two of them were standing alone in the parking lot when Parra gave him a fixed look: “You know what, boss? With this operation we just did, the two of us? We are tuqui tuqui lulu.” Parra motioned with his hands in the shape of a pistol, pointing it first at Oviedo’s head and then at his own to indicate that they were dead men.

But when he informed Iván Velásquez and other colleagues at La Alpujarra of his findings soon afterward, Oviedo found them in an exultant mood. J. Guillermo Escobar gave him a big hug: “Dr. Oviedo, with this operation you just justified your existence on earth. You have just saved not ten, not twenty, nor one hundred people. You have just saved thousands of people.” Oviedo would cherish J. Guillermo’s words, loaded with such emotion and coming from such an eminent figure, for years.

Over the next days, prosecutors and investigators pored over the documents they had found: it was hard to believe, but they appeared to be the entire accounting records for the ACCU for several years. “We had expected to find a place where they were making camouflaged uniforms, or to find weapons or money or drugs,” recalled the prosecutor Javier Tamayo. This was the only time he could remember investigators finding such a significant cache of records for an armed group. The records included information about the ACCU’s bank accounts, records of payments, and contributions of money and weapons made by various individuals, whose names were listed. There was a chart showing the ACCU’s organizational structure, divided into dozens of blocks, or fronts, and lists of the expenses of each of these fronts (some of the documents sought to disguise the fronts by referring to them as various named “farms,” but the investigators quickly figured that out). They also found records of extensive weapons purchases, labeled as receipts for purchases of ordinary items—nails rather than ammunition, clothes rather than military uniforms. The records showed that the ACCU was operating not only in their known haunts of Antioquia and Córdoba, but also on the eastern plains, the northern coast, Cali, and Bogotá.

Velásquez began to issue orders—around five hundred of them in just the first couple of days—to freeze the bank accounts of people and businesses that appeared on the paramilitaries’ books. Oviedo dispatched investigators to personally carry the orders to banks in towns and cities across the country. If they could only spend enough time working with the records, Velásquez and Oviedo were convinced that they could identify and arrest not only the paramilitaries’ members and leaders but also their financial backers. It could be a fatal blow to the ACCU.

In the following days, prosecutors also interviewed the three people they had arrested at the site, though the interviews were initially less than productive: the two women said they had only recently been hired to help Jacinto Alberto Soto; they were doing some accounting work related to what they had believed to be farms. Meanwhile, the heavy-set, green-eyed Soto acknowledged that he had been a member of the ACCU for a couple of years, and provided some more details about what the various documents meant. But for the most part, he denied knowledge of how the paramilitaries worked or who financed them, pointing out that he simply did the accounting based on information provided by other contacts in the ACCU. Still, Oviedo kept Soto in the CTI’s jail and ordered that security around the jail be strengthened—they didn’t yet know how much information he had to share, but the paramilitaries would have good reason to try to bust him out or kill him.

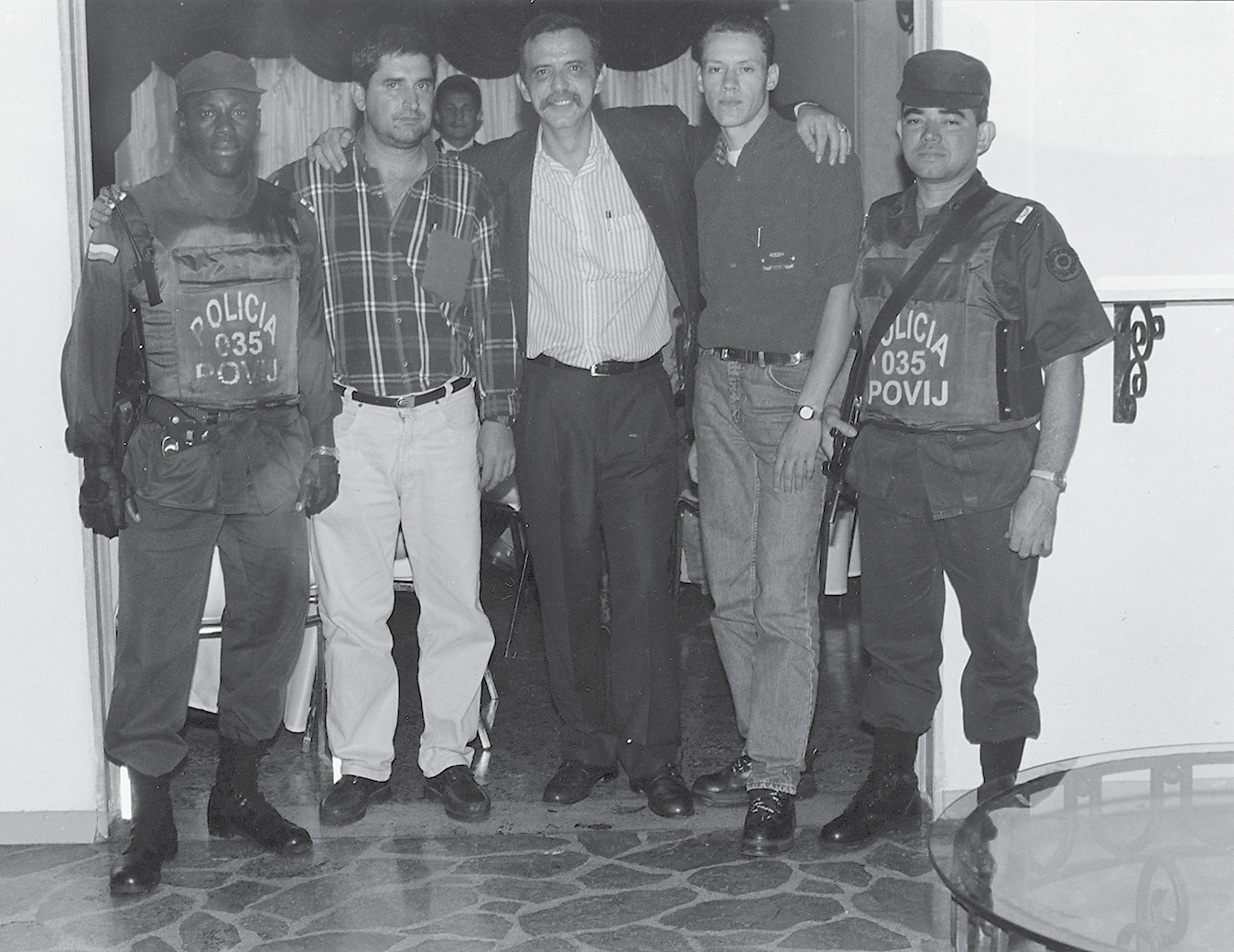

Iván Velásquez with bodyguards and investigators, 1998 or 1999, Medellín. © Iván and María Victoria Velásquez.

IN BOGOTÁ, Amelia Pérez, the Human Rights Unit prosecutor in the attorney general’s office who was married to Oviedo, was juggling many difficult cases. Not only was she still working on the Upegui investigation in Medellín, but she had also been assigned the El Aro massacre, which senior officials had decided to move from Antioquia to the specialized Human Rights Unit. And she was making progress on an investigation into another paramilitary massacre from December 1996 in the town of Pichilín, in the coastal state of Sucre (which borders Córdoba on the north). The story the survivors told was that around fifty paramilitaries had come into town and sacked the homes of several of its inhabitants, pulling more than a dozen of them from their houses and killing them in public, then leaving their bodies strewn along a main road.

In the El Aro investigation, Pérez found that she couldn’t get to the scene of the crime, which she wanted to inspect. She needed the governor’s office and military to provide security and transportation support—standard in other cases where crime scenes were hard to reach—but they kept refusing, giving her different excuses. One day they would say that there was combat going on in the area; another they would claim the weather would not allow it. It was the same experience that previous prosecutors in the case had had: Amparo Areiza, the daughter of the El Aro shopkeeper and the woman who had tried to piece the story together with Jesús María Valle, had for months tried to get to El Aro to pick up her father’s body, but when she tried going on her own, the army stopped her on the way, saying it was too dangerous. Prosecutors had repeatedly told her they couldn’t get cooperation from the military to conduct exhumations. Finally, a prosecutor had called her in late March 1998 to tell her that they were taking advantage of the fact that the Fourth Brigade commander, Carlos Ospina, was out of town to go into El Aro. Areiza had gone on foot and met prosecutors there while they did the exhumation. She then put her father’s remains, now mostly bones, into a suitcase, and left town carrying him on her back.

Months later, also facing what looked like obstruction from the military and others, Pérez was doing her best to get information from other sources. She started to compile information about the military units that had been operating in the region at the time: given the military’s failure to help the community during the massacre, and the fact that the paramilitaries had been able to leave the region around El Aro with around 1,200 head of cattle, without the military stopping them, some level of collusion seemed likely.

She also interviewed survivors, who talked in detail not only about the killings, but also about several rapes of women during the massacre. Many of them were afraid to come forward, out of shame or terror: they had seen how the paramilitaries gang-raped, but also tortured and killed their neighbor Elvia Rosa Areiza.

Around that time, Pérez also started interviewing a source who gave her leads about both the Pichilín and El Aro massacres: Francisco Villalba, a twenty-five-year-old former paramilitary member who on February 13 had turned himself in to the CTI office in Santa Rosa de Osos, Antioquia, saying he was tired of killing and was seeking protection. The head of that CTI office, Yirman Giraldo, had been the first to interview Villalba, and had then taken him in to Medellín, where Oviedo and a prosecutor from Velásquez’s office also interviewed him. A skinny man from the town of Sincelejo, in the coastal region of Sucre, whose dark tan suggested he had spent a lot of time working or walking outdoors, Villalba said that he had been part of a paramilitary block run by Salvatore Mancuso that had carried out both the El Aro and Pichilín massacres. He provided extensive statements about both cases, recognizing his own participation in some of the killings—for example, he recalled beheading one young woman with a machete near El Aro.

Villalba said that he had joined the paramilitaries in 1994 because he was out of work, and Salomón Feris—who at one point headed a Convivir, but who Villalba said was the coordinator of the paramilitaries in Sincelejo—recruited him. Early on, Villalba recounted, he was sent to a ranch called “the 35” in Antioquia that belonged to the paramilitary leader Fidel Castaño, where the paramilitaries trained him. They taught him to use AK-47s, mortars, grenade launchers, and other equipment. The paramilitaries also required their trainees to prove their courage by dismembering people that the paramilitaries brought in from outside: “Every fifteen days they would take around… seven or eight people and throw them into the field to train.… They would tell one that you had to cut the person’s arm off, or split them open alive.”

Villalba identified some of the other paramilitaries who participated in El Aro, including the commanders known as “Cobra” and “Junior”—about whom the survivors had also spoken—as well as several of the men under him, including one known as “Pilatos.” And he corroborated what Pérez and others had suspected about the military’s involvement: he said that before entering El Aro, they had met with several members of the Girardot Battalion, along with paramilitary commander Mancuso. He also said that a military helicopter had stopped by during the massacre and dropped off more ammunition and medication. In fact, Villalba said, in response to one question, that he didn’t even realize that his membership in the paramilitary group was a crime—“Since I always saw them working with the police and the army, I thought that it was legal, and to coordinate massacres and those things, you did it with the police and the army.”

In El Aro, Villalba claimed, the town priest had also worked with the paramilitaries, talking with Mancuso in advance and giving Cobra a list of names of townspeople he thought were guerrilla collaborators (the priest denied this claim in his own testimony). He said that after the massacre, the paramilitaries left the cattle with Mancuso.

Pérez found Villalba to be a puzzling witness: she viewed him as a “cold being,” and “very strange.” Based on what she knew about the cases, she believed he often lied. But other statements he made did fit the evidence she was finding—including his statements about the involvement of the military, as well as his identification of other paramilitaries involved.

Much later, Amparo Areiza would learn that Villalba had admitted to being the man who had tortured and killed her father. When she saw his image, she immediately recognized him: this was the skinny man who had repeatedly threatened her, and finally told her that he didn’t want to kill her.

ANOTHER WITNESS GAVE Pérez an important lead connected to the Padilla raid. The witness was a former member of one of the Convivirs who said he had realized that his Convivir, called Nuevo Horizonte (New Horizon), was in fact a front for the paramilitaries, and that its members were killing people. So he had gone to the CTI and begun helping Pérez on a number of cases, including that of Pichilín. As she started interviewing him one day, she recalled, he made a casual comment: “Ay doctor, what a blow they dealt to the paramilitaries in Medellín…” She paused. What did he mean? The witness explained: the man they had arrested in the Padilla parking-lot shack, Jacinto Alberto Soto, was no mere accountant. He was the man known by his alias as “Lucas,” a heavyweight in the ACCU whose alias had come up repeatedly on the wiretapped calls from the safe house. Lucas was the group’s chief for finances, and someone very close to Castaño himself. Pérez got a portrait sketched based on the witness’s verbal description and sent it along to Velásquez.