The Third Dialogue on Applicability

In this dialogue Practitioner and Scholar compare usability with the capability approach. They realize their earlier ignorance about the broader objectives of usability to improve wellbeing and quality of life and they decide to give it another chance. They discuss the basics of the capability approach and its compatibility with usability from several angles.

They agree that both usability and the capability approach link resources to achievements. They notice that they have to advance from the narrow-goal orientation of usability to the more user-initiated application of technologies to ensure respect for the dignity of individuals. They speak about how certain users—whom they call devotees—prefer meaningful achievements over convenience; they term this conviction-critical use. They are not happy with the loose way in which “user” is defined in usability and call for normative accessibility, with a few well-articulated exceptions. They discuss the problem of adaptive preference and agree that usability takes appropriate countermeasures against it by giving users a first-hand experience with novel solutions.

Practitioner and Scholar conclude by rearticulating usability. They propose that its criteria be adjusted to tolerate emergent scenarios of use. Usability should allow users to elaborate their own goals and terms of appreciation that unfold during use. They adapt usability so that it is sensitive to human capabilities and call it applicability. Practitioner defines applicability as the extent to which a product can be applied by the widest range of users for appropriate, sufficient, and worthwhile achievements in their lives.

The dialogue begins …

P: Hi, Scholar.

S: Thanks for the discussion last time.

P: My pleasure. Do you have time for another talk now?

S: Sure.

P: Great.

S: So, what do you think? Are we making progress?

P: Well, I think … do you mind if I go straight to what I have in mind?

S: You’re not so sure about our progress?

P: You know how it is. You learn something, but at the same time you have so many new things to think about that it’s really tough to wrap your head around them. The more we discuss, the more questions I want to ask.

S: Fine. Let’s skip the small talk.

P: … that we wouldn’t have had anyway!

S: Right.

P: Okay. I think we were too hasty in deciding that the usability paradigm is ethically inadequate or too limited. Frankly, we hurried too soon to user experience and the worth of use. Sorry.

S: No problem. Why do you think so?

P: Usability is a ubiquitously applied concept for evaluating the quality of use. The ISO 9241 part 11 standard has become the well-recognized definition of the concept. It’s been repeatedly challenged, certainly, but these criticisms have been addressed in part 210, published later to supplement the definition in many essential respects. The standard links usability to the design process and user experience—and to a broader and more versatile value basis. It says that human-centered design “enhances effectiveness and efficiency, improves human well-being, user satisfaction, accessibility and sustainability; and counteracts possible adverse effects of use on human health, safety and performance.” I think we oversimplified usability in our previous discussion. The goals of the standard go beyond the creation of efficient and effective products that are used only for achieving instrumental goals. The standard explicates that usability is an element of a good life, including objectives such as wellbeing, accessibility, sustainability, and health and safety. Thus, considering usability only as a narrow measurement of performance wouldn’t do justice to the intentions of the standard as a whole, even though I don’t object to the way we interpreted the quantitative indicators.

Usability is an element of good life, including wellbeing, accessibility, sustainability, and health and safety (ISO 9241-210).

S: The standard doesn’t give particular advice on designing for a good life apart from the generic human-centered process.

P: Maybe we can address that. But let me continue.

S: Sure.

P: Usability is a ubiquitous term within human-centered design, going far beyond the focused standard definitions.1

S: Inclusiveness is somewhat in conflict with the definition set out in Part 11.

P: On the one hand, in my view usability is a broad landscape concept that’s applied with plenty of slack. On the other hand, the Part 11 definition is a prominent landmark within that territory. It provides a clear-cut framework for discussing usability. When we speak about Part 11, I think our discussion serves as a salient example of interpreting usability.

S: Fine. So you think usability and especially Parts 11 and 210 are ethically more relevant than we acknowledged.

P: Yes. And I consider it essential that usability is instrumental with respect to users’ abilities to achieve something with technologies. In its instrumentality and focus on achieving goals, usability comes close to the capability approach, which links justice to individuals’ capabilities to do and to be what they want, within reason.

S: I see. You’re claiming that if we create products that help people achieve their aims, within reason, our design improves justice.

P: That’s what I’m trying to say: usability aims at a better life at the level of human–product interaction and I think the capability approach is a more generic construct that is compatible with usability. This means that usability inspections could also be inspections of our design ethics. Usability as a proxy of design that contributes to the development of a just society would set a practical limit to our responsibility so that we don’t need to consider, for instance, aggregated happiness. We would avoid many problems.

S: Not all usable products are ethical. They can be designed for evil purposes.

P: Well, yes.

S: But I agree with you that we could go back to usability. Addressing usability would broaden our perspectives. We’ve talked about the ways we work and for whom we design. Now we can perhaps address the objects of our design more directly.

P: What do you think about my idea of linking usability to the capability approach?

S: I assume you took your promise seriously and studied the capability approach more closely.

P: I did.

S: Maybe you have a point. And you’re not the first one to notice a link between the capability approach and design in general.

P: I know. Ilse Oosterlaken (2013: 16) has already said that … I have a quote here … “capabilities can be seen as the implicit or ‘missing link’ between more comprehensive ideas of the good life and concrete technical artifacts” … and another … “[it] can help designers to explicitly and systematically reflect on their work in relation to social change and development, which should ultimately lead to designs that contribute more to the realization of the values at stake, like well-being, agency and justice” (ibid.: 6).

S: But without a compatible framework of evaluating the quality of use, the capability approach remains too generic.

P: You see. Usability lacks a link to broader discussions on values and justice, and the capability approach is not operational at the micro level of development that design typically represents. They need each other. We should discuss their mutual compatibility.

S: It might lead us to something. Perhaps we’ll identify how usability should be adjusted to make it more sensitive to human capabilities.2 But first, can you summarize how you understand the capability approach?

P: I think, or hope, I can explain the basics.

S: Perfect.

“Capabilities can be seen as the implicit or ‘missing link’ between more comprehensive ideas of the good life and concrete technical artifacts” (Oosterlaken 2013).

P: The capability approach is a complex concept that has been discussed, criticized, and defended widely and repeatedly.3 Its fundamental setting is, however, relatively simple, I think.

S: Right. And it is exactly what?

P: People may have commodities such as economic resources, products, and public services. It’s not important as such to address these when we assess justice, the quality of life, and wellbeing, because they are only means to achieve something else that can be valuable. However, commodities have meaningful characteristics that may be important for individuals. The characteristics contribute to individuals’ capabilities to do and be what they aspire to, within reason. Amartya Sen calls valuable beings and doings functionings. All functionings together make individuals’ life what it is. Functionings are things that happen in individuals’ lives. Individuals’ experiences of the functionings lead to subjective wellbeing or other achievements they appreciate.

S: Why are capabilities so essential?

P: Capabilities are at a junction point on this continuum from resources to achievements for several reasons. First, individuals have varying capabilities to turn characteristics into functionings. The things regulating the characteristic–functioning transformation are called conversion factors. They include individual factors such as physical abilities, sociocultural factors such as behavioral norms, and environmental factors like climate and infrastructure (Robeyns 2005). An individual is capable of turning resources into functionings only when the characteristics of resources are compatible with the conversion factors.

S: Can you give an example?

P: A newspaper is of little use to me if I’ve lost my glasses or otherwise can’t read the small font, if I don’t understand the language, or if there isn’t enough light to read. The focus on capability turns attention to individual and contextual differences and the individuals’ actual possibilities of making use of the resources. Things that are available in principle aren’t meaningful if they aren’t actually attainable.

S: Thanks.

The unit of evaluating wellbeing and development should be human capabilities that allow individuals to do and be what they want, within reason.

P: The capability approach is a “framework for the evaluation and assessment of individual well-being and social arrangements, the design of policies, and proposals about social change” (Robeyns 2005). Whether it is, or should be, normative or only comparative is a question of ongoing debate. The fundamental claim of the capability approach is that the unit of evaluating wellbeing and development should be human capabilities that allow individuals to do and be what they want, within reason. It expands the evaluation space of wellbeing from subjectively experienced happiness4 or the distribution of resources5 towards a more information-rich space consisting of individuals’ capabilities and agency. It’s based on economist and Nobel laureate Amartya Sen’s work, as we already discussed. Philosopher Martha Nussbaum and others have further developed the capability approach and made their interpretations that sometimes deviate from Sen’s.

S: Good. I think we’ll keep coming back to the basics later on. So are usability and capability compatible and linked? The links between design and the capability approach have been discussed, but now we’re speaking about usability and capability.6 Usability isn’t equal to design.

P: I don’t know, but I thought that we could discuss that. Maybe I took a short cut somewhere or maybe I’m just blinded by the similarity of the terms, but here’s how I see it. While the capability approach is an evaluative framework for the quality of life (Sen 1993), usability is a measurement of the quality of use (Bevan and Macleod 1994; ISO 1998; Bevan and Curson 1999). In the present technical world these are overlapping categories and separating the use of artifacts from human behavior and way of life in general is impossible. The idea of quality of use approaching the quality of life becomes more intuitive, if we consider artifacts not only as odd objects here and there, but as a ubiquitous ecosystem of products and services in which we live.

S: The capability approach hasn’t been developed to evaluate products.

P: But my hunch is, as I tried to say, that usability and capability could be applied together as two mutually complementing approaches to the ethical evaluation of designs. Applying them together could be a way to link what is instrumentally good within the limits of the context of use with what is ethically justified in life. This link, if strong enough, would make usability the operational arm of design that contributes to the development of a just society, while the capability approach would be the grounding body. Together they would help us design the right things correctly.

S: Maybe we can start by simply asking whether the capability approach says anything directly about products and their impact on the quality of life? Does that make sense?

S: I mean the capability approach usually deals with high-level concepts touching human life from an angle that’s much more generic than what design typically deals with.7

P: I agree. When Sen writes about capabilities he means things such as staying alive, which is, to put it mildly, a much more profound issue than being able to use a product. But products have a role in keeping us alive and leading meaningful lives.8

S: However, we can survive without many products.

P: Let’s not get stuck on that. Sen writes briefly about products like mobile phones (Sen 2010b), clothing and bicycles (Sen 1985; Oosterlaken 2009), and their impact on capabilities.

S: But these are sidetracks in his discussions, and the reason for mentioning bicycles, for instance, as far as I remember and understood it, is to give an understandable example rather than to draw an equivalence between a simple vehicle and the political freedoms that are at the heart of his interests.

P: Are you sure about that? According to the logic of the capability approach, there’s no difference in principle between democracy and a bicycle. If you don’t have the means to get to the voting booth, your constitutional right to vote is useless. You lack the positive freedom, the real opportunity, to have an influence. A bicycle might give you that. Without that bicycle, there’s no democracy, no freedom.

S: And the bicycle here is not only a physical object but also a metaphor for any means of mobility. You’re right. Practical means are equally as important as anything else.

P: There are so many systems in addition to bicycles and traffic infrastructure that have an impact on society’s fundamental functions and individuals’ wellbeing. We discussed this last time when you introduced the standpoint of the neighbor.

S: Yes. We live within such systems.

Usability and capability lay between means and ends, resources and welfare, goods and the good.

P: Usability is a quality of interaction between human beings and technology and an attribute of use that is crucial in including or excluding users. Design and usability as its result mediate and create interfaces between individuals, products, and services, and these—if their usability is suitable for their purpose—can be turned into things that are valuable. Being able to use something is like being literate. Don’t you agree?

S: That is a metaphor.

P: The digital divide is essentially about people being able to do things. Like usability, the concept of capability also lies between the means and ends of a good life, resources and welfare, goods and the good. It’s situated between what’s possible in principle and in practice, and what’s provided for people and what makes a difference to them. Both usability and capability are bridging concepts between the provisioning of resources and what people can actually achieve. And capability is a still-developing approach that’s fluid and can be adjusted to make sense for practitioners in different fields.9 This should include us. There should be space and tolerance to accept designers’ efforts to explore capability and try to link their concepts to it.

S: In some texts I’ve read about the capability approach, I noticed a tendency to embrace dogmatic purity. But go on.

P: I feel we’re in agreement that discussing the capability approach would make sense. As you said, the discussion has already started. However, what hasn’t been done, as far as I can see, in spite of the growing interest in applying capability to design, is an analysis of the compatibility between it and the evaluative frameworks within design, especially usability.10 So if we were to say something about that, it might be a novel contribution.

S: What do you think we should say?

P: Well, I think we already mentioned the similarity of the concepts in addressing the bridging of what is available in principle—I mean resources and systems—and actual achievement. Maybe next we could discuss liberty of choice, which Sen considers fundamental for the quality of life.

S: Fine.

P: A central principle in the capability approach is that individuals choose to ignore or reject a major part of the functionings that could contribute to subjective wellbeing simply because these functionings don’t match their preferred way to live. However, they need to be there because the choice is so essential. Thus, capability refers not only to individuals’ ability to do and be something, but also to their possibility of choosing what’s worth achieving. I have a quotation by Sen (1993) here. He says that “acting freely and being able to choose may be directly conducive to well-being, not just because more freedom may make better alternatives available.”

S: But if this is the case, isn’t it difficult to study the capabilities? We need to study things that are merely hypothetical choices that might perhaps never turn into real action.

P: That’s a reason why practical assessments often don’t measure capabilities, focusing instead on other factors. Functionings, wellbeing, and commodities are necessary proxies in practical evaluations (Robeyns 2006: 355). Other reasons to address functionings rather than capabilities are related to situations where an individual’s agency to choose can be ignored, because they may not be ready to decide for themselves or the choices for a good life are self-evident.

S: What do you mean?

P: We can assume that everyone would like to live without domestic violence, for instance. We don’t need to consider a scenario where someone prefers to be beaten up by a family member.

S: When it comes to design, I think safety is an equivalent example. We don’t need to consider giving people the freedom to choose hazardous products, with some rare exceptions.

P: Exactly.

S: This seems to make sense, but it also means that the capability approach doesn’t focus on capabilities.

P: The capability approach is complicated. It’s more appropriate to say that this approach enters the evaluation space of wellbeing and justice via capabilities, rather than focusing exclusively on them.

S: Can you try to link that to usability?

P: Sure. The definition of usability in Part 11 states that it is “the extent to which a product can be used,” which refers directly to something users are able to do. The standard also says that usability “is connected with the extent to which the users of products are able to work.” This says quite directly that usability is about measuring users’ capabilities, at least in the everyday meaning of the word.

S: But what can we say about the freedom of choice?

P: The standard doesn’t require actual use. A verified possibility of use is enough. What users, or actually the representatives of future users, do in a usability test and how satisfied they are with the product are accepted as proxies of what actual users could do in the future. That’s a good match with the capability approach.

S: True. The standard could have formulated usability as “the extent to which a product is used” or as “attributes that bear on the effort needed for use,”11 or as something like “a person’s perceptions and responses resulting from the use.”12

P: But it did not.

S: No. The first alternative wording refers to actual doings.

P: You mean functionings in capability terms.

S: Yes. The second refers to characteristics available for the user and to resourcist evaluation à la Rawls. The third refers to the individually experienced results of use.

P: Part 11 (ISO 1998) has been anchored to users’ abilities to convert means to ends. This is one of the possible units of evaluation that theories of distributional justice disagree on. It enters the evaluation space of quality of use in the same way as capability enters the evaluation space of wellbeing, justice, and quality of life.

S: You’re right.

P: Capabilities refer to the things individuals might choose to do if that is their preference. Thus they deal with hypothetical future options. This aligns capability evaluations close to the problems we have in conceptualizing future interactions and designs.

S: I never really thought about that, but according to Part 11 usability really doesn’t require a system to be used for it to be usable. The most usable product might be one that is never used.

P: Usability through ignorance!

S: Indeed. This compels us to look at how the encounters between technologies and humans that actually take place, or may take place, can be used as proxies of defining usability in hypothetical encounters in the future. As you said, the capability approach prefers to stick to capabilities, because they refer to both selected and potential functionings, and thus limit the evaluation space to the feasible options and individuals’ freedom to choose. Usability seems to share similar intentions. Those systems that are usable are possible choices for an individual and the more usable systems there are, the more attainable choices individuals have.

P: I wonder why usability focuses on options rather than actual use.

S: I would try a historical explanation. The development of Part 11 took place in the late 1980s and in the 1990s.13 That was an era when information technology migrated from specialized solutions for trained users to standard office equipment and eventually to consumer commodities. This migration was accompanied by a change in product development practice. The previous model of developing systems for a clearly specified use and identified user groups changed to designing off-the-shelf commercial products. It became necessary to think about usability as the ability of a potential user who is not known to the developers rather than as a measure of the performance or satisfaction of a known operator. The focus on hypothetical use may also have been inherited from the separation of the activities of design and use. Even though usability is a “quality of use,” we position usability engineering in the processes of design and development. Before a system is ready, installed, and adopted, the use that can be studied, evaluated, and improved is hypothetical. The use and thus the users don’t exist. Thus we can only specify hypothetical options that might later turn out to be representative of users’ actual behavior.

P: The separation of design and use has been criticized.

S: More recently. That’s because the process of adoption is complicated and involves users’ innovations. Products are not merely used for “achieving specified goals” as the standard defines—the goals tend to change as products find their roles in everyday practices. Thus, the “post-usability era” of human-centered design has been increasingly interested in what technologies are actually used for and how the options and restrictions inscribed during the design phase unfold. The idea of a product as a coherent piece of equipment has given way to the concept of flexible platforms that active users configure to match their needs and allow them to achieve goals that they define.

P: If the definition of usability were written today, it would address adoption, how products actually become useful or enjoyable and how they are actually used rather than how they could be used.

S: Most likely.

P: In capability terms, the attention has shifted towards functionings.

S: Functionings and wellbeing I would say.

P: The conclusion, however, seems to be that usability and capability share the same entry point into the evaluation space via addressing potential future use.

S: That seems to be the case. The similarity is not intentional as the motivation and justification have been different, with one looking for distributional justice and the other for commercial mass acceptance. However, the resulting formulations are rather similar.

P: There’s one more thing related to the freedom of choice.

S: Yes?

P: The focus on freedom to choose doesn’t only mean that an individual should be able to choose between different ways of enhancing her wellbeing. Capabilities also include choices that lead individuals to sacrifice their wellbeing for a worthy cause.

S: Choosing to suffer is seen in a positive light.

P: Yes. In this respect, the capability approach is different from utilitarianism. Hedonic happiness is not the ultimate goal in life, and consequently it shouldn’t be the unit used to evaluate the quality of life. People voluntarily compromise their wellbeing for the benefit of others or other causes. They experience negative feelings, stress, or physical suffering, or willingly risk their personal comfort or safety, but still choose to do what they consider to be the right thing. The capability literature frequently refers to political activities such as hunger strikes as examples of people choosing to suffer for what they regard as being more important than their personal wellbeing (Robeyns 2005; Sen 2010a; Nussbaum 2011). That’s why the evaluation of capabilities involves individuals’ opportunities to advance their own wellbeing and also voluntarily suffer for a relevant reason.

S: If they voluntarily choose to suffer they might feel some sort of pleasure from being faithful to their principles, but let’s not get stuck on that.

P: To formalize the vocabulary of choices and gains, Sen (1993) has separated wellbeing from agency, and achievements from freedoms, thereby creating four categories of evaluation. These are “well-being achievement,” which is something actually completed to enhance personal wellbeing; “agency achievement,” which is something valuable completed for a cause other than personal wellbeing; “wellbeing freedom,” referring to an option to choose functionings for personal wellbeing; and “agency freedom,” which allows a person to choose to do something for a more relevant cause than her wellbeing.

S: Right. So now the question is how does usability conceptualize the agency achievements and freedoms. Or does it?

P: Yes.

S: What do the definitions say?

P: Part 11 (ISO 1998) mentions satisfaction as a usability criterion and defines it as “freedom from discomfort, and positive attitudes towards the use of the product.” Part 210 (ISO 2010) further emphasizes the wellbeing angle, stating that “when interpreted from the perspective of the users’ personal goals, [it] can include the kind of perceptual and emotional aspects typically associated with user experience, as well as issues such as job satisfaction and the elimination of monotony” and that the “resulting human activities should form a set of tasks that is meaningful as a whole to the users,” and that user experience “includes all the users’ emotions, beliefs, preferences, perceptions, physical and psychological responses, behaviors and accomplishments that occur before, during and after use.” Thus usability clearly includes wellbeing.

S: Yes, but it’s not as obvious that agency and compromising wellbeing are usability goals.

P: Let me think about this …

S: Take your time.

P: Well, here’s a typical real-life example. The use of technologies may cause suffering or mild frustrations at least. Use doesn’t necessarily lead to personal satisfaction, but the products and services are used for other purposes that are more important than wellbeing achievements. In spite of her dissatisfaction, a user may volunteer to use a product because she believes that’s the only or best, perhaps the most effective and efficient, way to behave so as to yield more valuable results than her own happiness.

S: Many of the administrative computer programs I use are like this. They are really annoying but still I use them.

P: I believe we all have experienced such frustrations. The objective performance criteria of usability are effectiveness and efficiency. They—or actually the accuracy and completeness of results that’s part of both of them—are beneficiary-neutral, unlike satisfaction.

S: What do you mean?

P: I mean they refer to benefits that may belong to parties other than the operator herself. So the way usability is defined doesn’t exclude agency achievements.

S: Excluding satisfaction.

P: Yes.

S: We need to accept that the operator’s subjective satisfaction might have to be ignored or compromised. Otherwise usability covers altruistic motivations for use, although it doesn’t underline that aspect very clearly.

P: The standard (ISO 1998) actually explicitly acknowledges this issue by stating that in the case of safety-critical and mission-critical systems “it might be more important to ensure the effectiveness or efficiency of the system than to satisfy user preferences.” That seems to include agency achievements. The requirements of capability set by agency freedoms would suggest that satisfying performance criteria rather than satisfaction should be given priority also when the use is “conviction-critical.”

S: Conviction-critical? That’s a new idea.

In mission-critical use, external forces compromise the user’s satisfaction. In conviction-critical use, the user’s values compromise satisfaction.

P: I think we might need one here. By conviction-critical use, I mean interaction in which the user’s firm beliefs regarding appropriate, just, and worthy behavior are given more weight than his or her personal satisfaction. Such users are ready to compromise their comfort and accept pain, frustration, and other such negative subjective consequences in order to do what needs to be done. In mission-critical use, external forces such as the danger of a traffic accident set obligations to compromise operator wellbeing and satisfaction. In conviction-critical use, the obligations are internal, emerging from the user’s own values and principles such as a commitment to ecological choices.

S: This user is neither an operator nor experiencer in terms of her attitude.

P: No, she isn’t. We seem to have three separate cases when it comes to the subjective pleasure of use. First, we have an experiencer. She is motivated by the pleasures of use, and she uses the product because it provides a rewarding positive experience. Second, we have the operator, who uses the product to achieve goals external to the use itself; in her case, user inconvenience is a problem and she needs to be cushioned against it. She is sensitive to discomfort and if the product is too inconvenient, she will quit using it.

S: Or she needs to be compensated more.

P: Exactly. Third, we might have devotees who don’t mind the effort and struggle, but use the product owing to the importance of the outcomes.

S: True. Do we have a new standpoint? What shall we call it?

P: Devotee.

S: Devotee?

P: Why not?

S: That’s a good name. But it seems to me that a devotee’s interests are the same as those of a beneficiary. She ignores her own dissatisfaction with the interaction.

P: Beneficiaries don’t operate the product, but devotees do.

S: True. But aren’t these devotees a rather marginal group?

P: I don’t know. You just said you keep on using your admin software. We all use terrible systems because we’re committed to getting things done. Maybe we, the whole discipline, have been too carried away with looking at the issue of pleasure. Really, think about the things that people do, especially at work. Many of these things are necessary rather than entertaining. And we often use devices and systems because they are necessary for working effectively as responsible professionals, and not only because we are paid to use them by our employers. At least I believe that modern professionals do frustrating things because they feel these things are part of their responsibilities rather than their obligations. But obviously, completely voluntary action would be a clearer example.

S: Many are ready to walk an extra mile for sustainable choices, because they believe in doing the right thing rather that enjoying doing it.

P: True … Summing up, I think we’ve agreed that usability aims at ensuring users’ wellbeing even though it has been criticized for its narrow focus on goal achievement. It’s not as clear whether usability recognizes users’ agency, but the beneficiary-neutral performance criteria make it possible to focus on agency achievements and freedoms. We only need to remember that use can be mission-critical and conviction-critical, not always aiming at subjective satisfaction. Usability can also be used to evaluate the quality of use from a devotee’s standpoint.

S: I agree. What next?

P: What about this? Human capabilities are amalgam concepts consisting of inherited and learned competences together with the opportunities provided by the environment.14 They combine individuals’ inherited potential, upbringing, learned skills and predispositions, material objects, sociocultural resources, and other contextual opportunities. What is biologically human, social, and cultural and what is artificial don’t appear as separate categories, but as a single system of capabilities.

S: Combined capabilities seem to be close to many other approaches that regard human actors, environment, and artifacts as a single system rather than separate entities (Coeckelbergh 2011; Verbeek 2011).

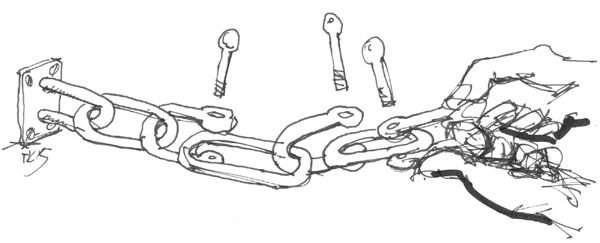

P: Yes. A person, a road, and a bicycle are not separate elements, but a system of riding and the capability to ride.

S: Usability is a similar construct in this respect. It is “a property of the overall system: it is the quality of use in a context” (Bevan and Macleod 1994). It includes the working practices, the product, individual differences between users, and so on. The attributes of a product are only one element of the quality of use in an overall system. Usability is always studied in relation to users, goals, and context and it doesn’t refer to product properties or the users’ abilities separately, but instead requires a system view. It’s often criticized for its overly narrow definition of what constitutes a system, but the idea of a system-level approach lies at its core.

P: Thus usability is like combined capability. I think the main difference is the point of view. Usability approaches apply a product point of view while the capability approach adopts a more human perspective.

S: Considering the explicated system approach of usability, the wording of the Part 11 definition is somewhat in conflict with this approach in that it clearly separates “a product” from “users.”

P: Can you explain?

S: In using and being used, the user and the object of use became inseparable and together constitute something that can be evaluated in terms of usability. “Interact,” “assimilate,” or “adopt,” for instance, would be better terms than “use” for describing the shared agency of human and artificial actors. I think in this respect as well the standard would be worded differently if written today. It wouldn’t say “the extent to which a product can be used by specified users” but instead something like “the extent to which a product can be applied by specified users.”

P: By “apply” you mean something like “make relevant.”

S. Yes. That would underline the reciprocal process of domestication, absorbing, integration, and digestion in addition to use. It would also recognize the possibility that in some respects products can be seen to be using users.

P: They make us do things.

S: And they should to some extent. At least they should nudge us to do good things rather than bad.

P: I think “apply” is more compatible with human capabilities than “use.” It’s also less paternalistic.

S: True. It allows the users to deal with and appreciate the products on their own terms.

P: May I continue to another angle of the capability approach that might be relevant here?

S: Sure.

P: According to the capability approach, the reason why individuals may not be able to turn resources into functionings is that there are restricting factors that are related to personal abilities, social settings, and environmental conditions (Robeyns 2005). These are called conversion factors. Physical abilities, for instance, set limits on how much one can get out of certain resources. A disabled person cannot ride a bicycle.

S: Not a standard design in any case, depending on his disability.

P: Yes. Also, social and cultural factors and environmental conditions influence what kinds of resources are needed to achieve goals. Infrastructure and weather conditions influence what is sufficient for an individual to have adequate shelter. Thus the capability approach underlines the importance of the proper scrutiny of conversion factors.

S: Usability is often associated with usability tests conducted in laboratories. These aren’t able to capture the impact of social and environmental conversion factors. Thus it might be that usability addresses a narrower range of capabilities than the capability approach.

P: The standard doesn’t advise sticking to laboratory settings. That’s just an easy way to evaluate something. Part 210 actually encourages us to go into the field.

S: Okay. You’re right.

P: Technology provides potential for functionings, but individual and contextual factors can limit whether it really can be utilized (Eason 1984, Nielsen 1993). Resources aren’t enough if they cannot be turned into valuable ends in practice, and usability is the angle to address the conversion. Part 11 explicitly recognizes conversion factors, including users’ abilities and the context of use. It (ISO 1998) lists users’ characteristics, including “knowledge, skill, experience, education, training, physical attributes, and motor and sensory capabilities.” The focus is on skills to use technology and skills with the tasks. By “a specified context of use,” Part 11 refers to the “relevant characteristics of the physical and social environment … wider technical environment … the physical environment … the ambient environment … and the social and cultural environment.” The last one includes work practices, organizational structure, and attitudes. All of those seem to be compatible with what the capability approach means by social and environmental factors.

S: True. But the whole point in the capability approach is to address the just distribution of capabilities, and the way in which it suggests we should deal with the conversion factors has to be based on just distribution. This emphasis is missing from usability or at least it’s not part of the main message.

P: Perhaps.

S: By the way, did you say something already about the way the capability approach suggests that capabilities should be distributed?

P: No, I didn’t. And that’s perhaps one of the main weaknesses of the capability approach. One of its main principles is, however, to consider each person as an end (Nussbaum 2000: 74). Here the capability approach subscribes to Immanuel Kant’s categorical imperative in its second, not so well-known, form, requiring us to consider everyone as an end and never only as a means. The principle means that the conversion factors need to be addressed at the level of individuals, and aggregated indicators of wellbeing and justice have to be avoided. The norm15 for the fair allocation of resources and development of capabilities is that such provisioning should be arranged to ensure that it compensates for the shortcomings of each individual in order to enable them to enjoy levels of combined capabilities that clearly meet the minimum threshold (Nussbaum 2011: 36).

The capability approach subscribes to Kant’s categorical imperative, requiring us to deal with everyone as an end and never only as a means.

S: Where should the threshold be set?

P: There is no exact answer. But when we deal with users who are close to the threshold of having sufficient capabilities, technology should be seen to compensate for the uneven spread of conversion factors and contribute to equal opportunities—or if not equal, at least sufficient.

S: This type of egalitarian motivation stretching to some sort of positive discrimination doesn’t belong to usability thinking. Or maybe I could say it more strongly: it has no role in usability.

P: This is understandable as usability isn’t typically limited to the most essential capabilities for human dignity, which the capability approach focuses on.

S: Right. Usability evaluations apply to all tasks instrumentally necessary in goal-oriented interaction. Some of those require special skills that go beyond what we can reasonably assume everyone is capable of doing and being. Not everyone needs to know how to drive a train, because that isn’t an essential capability for human dignity. Being able to ride a train is another issue entirely. But when we deal with capabilities at a more general level of relevance, usability can be complemented with the requirement of accessibility. Part 210 (ISO 2010) defines accessibility as “usability of a product, service, environment or facility by people with the widest range of capabilities.”

P: ISO doesn’t require that usability should be interpreted as accessibility.

S: It doesn’t, but it should when the interaction deals with capabilities closely associated with central capabilities. Nor does it prioritize compensating for the lack of capability. Improving the performance of the most capable individuals to even higher spheres as well as giving the least able better access to basic functionality can both yield usability gains. Even though that isn’t a typical emphasis in accessibility, the definition can also be considered as a reminder or request that we should make sure that the most capable individuals have the opportunity to employ their competences to the fullest.

P: True. I hadn’t thought about that.

S: Me neither. It just occurred to me.

P: I agree that usability could’ve been defined much more strictly in this respect. Instead of saying “the extent to which a product can be used by specified users” it could’ve said “the extent to which a product can be used by people with the widest range of capabilities.”

S: I’m not sure about this. Think about the train driver.

P: If we would allow the interpretation of “widest” in a relative and context- and practice-dependent manner, my formulation would work. The superlative doesn’t need to be unconditional. There are capabilities and lack of capabilities that go beyond the scope of “widest.” Trains and ticketing services should be accessible for the visually disabled and the blind. However, driving a train with poor visual perception goes beyond the limits of the widest possible capability for that responsibility. Thus “widest range” wouldn’t mean all-inclusive, but instead the widest possible range with reasonable and fair criteria.

S: I like that. Whatever we end up saying about usability and capability, I think this is something we should consider. The standard formulation of usability for “specified users” is too loose from the perspective of justice. Designers need to understand the fair exclusion criteria that the practice, context, and its requirements allow, and design so that all the others are included.

P: Excluding more than that would be discriminatory. There have to be well-founded reasons for exclusions.

S: I agree.

S: But do you think our discussion is converging on something? Are we approaching a conclusion?

P: Let me see. I’ll try to summarize.

First, we agreed that capability and usability enter the evaluation spaces of the quality of life and quality of use in similar manners, focusing on individuals’ abilities to convert resources into achievements. Second, in the case of both capability and usability, these abilities are seen as combined properties of individual actors and their environment. However, the replacement of “use” with another verb such as “apply” would better refer to the users’ active role, the combined nature of capabilities, and the systemic nature of use. Third, neither approach takes for granted that given resources would be of benefit to individuals; instead they both focus on understanding the impact of individual, environmental, and social conversion factors on attainable doings and beings.

Fourth, both capability and usability reject subjective satisfaction as the only criterion of quality. However, in conviction-critical cases of use, usability evaluators should give priority to beneficiary-neutral evaluation criteria and make satisfaction an optional criterion to respect the devotees’ motivation for the use of the product. Fifth, in ISO 9241, the definition of usability doesn’t assume that the evaluated use is linked to the essential and unavoidable human capabilities that are relevant for all individuals and set normative implications for design. If these assumptions are imposed, there is a need to ensure accessibility and that there are good arguments in favour of fair exclusions.

S: Impressive.

P: Thanks. I started to think that based on these findings we might be able to sketch a capability-sensitive version of usability. What do you think?

S: Or something reminiscent of usability but with another name, because usability is what it is. We cannot change it any more.

P: Maybe so.

S: There’s one more thing that I don’t understand yet. I think we should discuss it before trying to create anything new.

S: Individuals’ agency to choose their preferred goals is a fundamental value in the capability approach, but I guess it wouldn’t be possible to aim for unrealistic goals.

P: That’s a difficult one.

S: Sorry.

P: Sen and others stress a liberal and non-paternalistic approach to distributional justice and wellbeing. However, they also aim to avoid value relativism. Individuals’ choices need to be reasonable. How these reasons are defined, measured, and judged in the liberal agenda is a problem. The capability approach, for instance, struggles with the problem of expensive taste. Everyone should be able to be in public without shame,16 but is it fair if to do so I require a much fancier outfit than you do without a compelling reason? Sen has underlined the importance of public discussion to identify the relevant capabilities that everyone should have and their threshold levels. Nussbaum (2011: 33–4) is more explicit and has presented a list of central capabilities.

S: What are the central capabilities she lists?

P: Life. Bodily health. Bodily integrity. Senses, imagination and thought. Emotions. Practical reason. Affiliation. Other species. Control over one’s environment.

S: Thanks.

P: Her heuristics for putting items on the list is that sufficient levels of these capabilities are necessary for human worth and dignity. This means that subsistence doesn’t define the minimum level; the threshold is set in terms of what is needed for individuals’ worth and dignity. This means that each individual should be dealt with as an end, as I already said, and not as a means for something or for somebody else. An instrumental attitude to dealing with individuals leads to exploitation and humiliation. Thus, satisfaction and suffering as qualities of life cannot be evaluated from the point of view of justice and wellbeing without placing them into a context that pays attention to human worth and dignity. Suffering because of unavoidable circumstances may be a humanitarian tragedy, but doesn’t necessarily violate individuals’ dignity and is thus less devastating than unjust decisions about the distribution of capabilities (Nussbaum 2011).

S: Can you elaborate on this from the usability angle?

P: I’m not sure. Usability doesn’t say much about how it deals with human worth and dignity.

S: That’s not quite true. Part 11 mentions sustainability and social responsibility. Part 210 (ISO 2010) says that human-centered design supports economic, social and ecological sustainability and it refers to Bruntland’s commission report (United Nations 1987). Part 210 claims that “a human-centred approach results in systems, products and services that are better for the health, well-being and engagement of their users, including users with disabilities.” Apart from that the standard doesn’t discuss ethical norms. How the promise of social sustainability is interpreted in the other parts of the standard isn’t transparent.

P: There might be more than that.

S: What do you think?

P: I have a hunch that the goal of use being efficient and effective is somehow related to human worth. We might be able to find something even though the standard isn’t explicit in this respect.

S: Well, if using products is seen as an instrumental means to achieve goals, the question about the dignity of effectiveness and efficiency is irrelevant or at least not very interesting. The goals are definitive, and effectiveness and efficiency are just technical measurements.

P: That might be a simplified view. We’ve discussed that already.

S: True.

P: Technology is not just a means but also a component in a more complicated reciprocal system involving human capabilities and agency. This system functions as part of individuals’ life in society and the qualities of use can and should be seen as qualities of life. Thus the criteria set on the quality of use should address a more comprehensive entity than use in an instrumental sense.

S: So let’s see if we can say more about effectiveness and efficiency.

P: Part 11 defines effectiveness as “accuracy and completeness with which users achieve specified goals,” and efficiency as “resources expended in relation to the accuracy and completeness with which users achieve goals,” as we already said. Do you agree that “accuracy,” “completeness,” and “resources” are the key words?

S: Yes.

P: They are reasonable indicators of the quality of use, but only within well-defined systems where the ideal goal and course of action are known.

S: What do you mean?

P: “Accuracy” implies that it’s known what is correct and precise and, according to the standard, both good and desirable. Evaluating something in terms of accuracy requires that the exact location of the target is known so that the deviation can be measured. If we don’t know the goal of an activity, we cannot measure the accuracy of the tools employed. “Completeness” implies that it’s known what constitutes the whole amount, and thus what is necessary, enough, or perfect. We cannot measure completeness without knowing how much is “all.” We need to know what the full amount is. “Resources” implies that what is considered as expenditure and thus avoidable is known. Calling something a “resource” implies that the entity isn’t important as such but instrumental in achieving something else. It’s something that is consumed during use, something whose value decreases with use. Time is a resource when its value decreases when it is consumed for a purpose.

S: Here we return to the topic of our previous talk. These assumptions are hypothetical when it comes to using technologies.

P: Yes. With the exception of well-defined goal-oriented tasks, use and its goals unfold together in a dynamic manner, the standpoints of sponsors, operators, beneficiaries, experiencers, and neighbors become valid and cease to be valid and re-emerge, and the value of inputs and outputs may change during the course of action. It seems that accuracy, completeness, and resources create an overly tight framework from the perspective of dignity. When the goals defined for evaluative purposes match the actual experienced nature of the tasks, everything is fine and fair from the point of view of the stakeholders. If there’s a mismatch between the actual dynamically developing goals of life and work, and the rigidly applied criteria of effectiveness and efficiency don’t match, then we face experiences of humiliation and disrespect.

S: Do you mean something like this: If you use a tool, say 3D design software, to learn a new skill or to gain a firmer grasp of certain nuances of your trade, and if your superiors evaluate your performance in terms of efficiency criteria, you feel your efforts aren’t respected.

P: Yes, but even that is a simplified example.

S: I see your point. There might be much more fine-grained situations where an approximation of the goal of use against which the use is measured is different from the actual goal that emerges when the design is used. John Rawls (1971: 440–6) says that the basis for self-respect is the most important primary good that needs to be provided. Without self-respect, people don’t see the worth of their life projects and believe what they do is without meaning or they stop striving to achieve anything that is valuable for them and others. The support for and fair appreciation of our efforts is essential, and if our efforts are rejected or criticized based on terms that are irrelevant for our life projects and goals, the effect is frustrating. Perhaps also MacIntyre’s (1981/2011) opinions about the internal goods of a practice, the development of which makes us virtuous practitioners, are relevant here. But now we’re building a long bridge from the way our use of gadgets is evaluated to how our self-respect and dignity is respected.

P: If we want to be consistent in saying that technology is an important component of the quality of life, we have no choice. If we as professionals have to work with tools whose use is optimized in accordance with criteria that aren’t in harmony with the way we and our colleagues understand the virtues of our practice, we feel that our worth as professionals is ignored and we become frustrated. In simpler terms, think about design software that limits your freedom of expression. I’m trying to say that if the quality of use is evaluated based on fixed ideas about its goals, we run the risk that these ideas are wrong. If they are, frustrations will occur.

S: Individuals’ behavior when they seek to achieve doings and beings that are relevant for wellbeing, worth, and dignity is also goal-oriented, even in cases where the goal isn’t very clear. In this respect, the ethically relevant capabilities and what usability measures aren’t different.

P: But the problem really is that trying to achieve health, rewarding social relationships, or meaningful ways to contribute to society aren’t tasks that can be exactly defined, and usability requires us to be exact in our specification of goals. If we design something for social connectivity, it would be insulting to set a fixed number of new acquaintances you should aspire to link up with. The goals can be defined only in very rough terms. The ill-defined nature of life projects has an impact on the ways artifacts are used in life projects. Browsing the Internet is a serendipitous rather than focused activity—the results and intermediate results are emergent rather than specified a priori.

S: Fine. This echoes the old criticism of usability being too goal-oriented. Now you’re saying that’s not only a validity problem, but also related to usability being paternalistic. It builds on designers’ assumptions.

From usability to applicability

P: What if I can fix the problem? An idea occurred to me.

S: That would be amazing. What do you have in mind?

P: Let’s see if this leads to anything. But the idea is this. The elements used to specify performance in Part 11 are only meaningful for well-specified tasks. However, the definitions of the usability criteria could be relaxed without breaking their logic.

S: What do you mean?

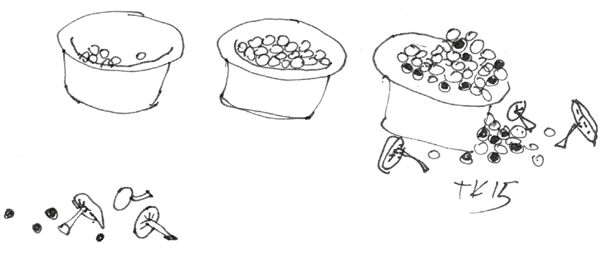

P: We don’t necessarily need to know the target of the use and the value of resources if we adjust the definition slightly. Accuracy, completeness, and resources have parallels that share the same essence, but don’t require us to assume well-defined goals. Accuracy without a priori knowledge of what is correct is …

S: You tell me.

P: It’s close to “appropriate.” The idea of appropriateness deals with something that is relevant and hits the point, but doesn’t require us to know the exact target before we reach the goal. It tolerates that we define and achieve the goal simultaneously. We go picking berries but find mushrooms instead. Our haul doesn’t meet the initial specification but it’s still appropriate. Completeness without an a priori set value for the full amount is “sufficiency.” How much is sufficient becomes known when it has been collected, but not necessarily before. A “complete” exercise is one that has burned a defined amount of calories. A “sufficient” level of exercise is right for the circumstances where I exercise and might be less or more than the “complete exercise.” A “sufficient” amount of berries picked might not amount to a full bucket; depending on the circumstances, half a bucket might be a good achievement, while there are times when more than a bucket would be “sufficient.”

Accuracy, completeness, and resources have parallels that share their essence, but don’t require well-defined goals.

Rephrasing usability so that it assumes tolerance for emergence would make it more applicable for ethical evaluations of use.

S: What about resources?

P: Resources in Part 11 mean “mental or physical effort, time, materials or financial cost.” The standard assumes that spending these decreases the quality of use.

S: This doesn’t need to be the case, as we discussed.

P: Exactly. Mental and physical efforts can be rewarding and essential for human flourishing. Time and money invested in the use of a product can be indications of value rather than expenses. Instead of considering that spending effort, time, and money inevitably decreases the quality of use, we could look at them as indicators of value or worth. The worth of time spent on use can be positive or negative. If we find berry-picking rewarding, spending a longer time in the forest is a gain and doubles the wellbeing achievement; if it starts to rain or there are too many aggressive mosquitoes, we stay in the forest only as long as it takes to pick the berries, and the time there is a necessary evil to be minimized.

S: You propose that appropriateness, sufficiency, and worth should replace accuracy, completeness, and resources.

P: Perhaps I’m asking rather than proposing. But I believe they might help us to discuss and question how we express desirable qualities of use when the tasks are ill defined. Using them, or similar criteria that have a tolerance for emergence rather than accuracy, completeness, and resources would help us to ensure that the quality of use is evaluated in ways that are sensitive to what makes life worth living. Rephrasing usability criteria to assume tolerance for emergence would make them more applicable for ethical evaluations.

S: Makes sense. I agree.

P: Great.

S: In addition to what you said, we need to remember the previous changes to usability we discussed earlier. Do you still remember those?

P: I’ll try to summarize. We wanted to replace “use” with “apply” and we wanted to be stricter with how we choose the users. Satisfaction should also be an optional criterion because of conviction-critical use.

S: I think we need to return to satisfaction.

P: Do you have something to add?

S: We’ve ignored one interpretation mentioned in Part 11 (ISO 1998). It says that satisfaction can also refer to “the extent to which particular usability objectives such as efficiency or learnability have been met.” I think we should take a stand on that. This interpretation is different from what the capability approach requires, isn’t it?

P: It is kind of utilitarian.

S: Exactly. Satisfaction becomes a single summary criterion like happiness in utilitarianism.

P: And the capability approach rejects satisfaction as the single criterion of wellbeing and the quality of life. There are several reasons for this. The importance of agency, we’ve already discussed. Adaptive preference is another reason. People formulate their preferences based on comparisons: what they have or want to have are compared with an available reference level. The things people have experienced themselves and what they regard as attainable future options set limits to what they want. Me desiring, or tolerating, something is not a question of absolute levels of quality, but a comparison I make between my actual situation and a reference level that I consider reasonable. People living in substandard conditions might not see a flourishing life as an option and thus adjust their tolerance to accept their suffering and don’t see it as suffering.

S: People also adapt to luxury, starting to regard it as the norm (Frank 1999; Layard 2005; Teschl and Comim 2005).

P: Exactly. So the capability approach takes the stand that the fair evaluation of wellbeing and distributional justice has to be based on a more information-rich evaluation space than individuals’ subjective satisfaction.

P: Sorry.

S: Referring to adaptive preference has been an argument against human-centered design, too. Its opponents say laypeople are so used to their habits that they cannot see any other options apart from small improvements to the existing systems. This being the case, asking them makes no difference.

P: Do we ask when we evaluate usability?

S: Usability has a strong behavioral component. It underlines the importance of not trusting subjective responses only. When evaluations of subjective usability are based on individuals’ immediate first-hand experience with new products, the evaluations are grounded on actual performance and experience of it, which is—if not completely but to a remarkable extent—independent of the user’s adaptive preference. The evaluation procedure itself creates a level of reference, because the user gets first-hand experience with the object of evaluation during the test.

P: Comparing routines and long-term preferences to new and perhaps radically different solutions, which are presented as partly working prototypes, is not a fair comparison. Resistance to change may ally with adaptive preference and lead to conservative preferences.

S: However, the experiment-based approach, giving the users first-hand experiences with alternative capabilities and applying both objective and subjective criteria, is a good strategy for resisting adaptive preference.

The close link between embodied interaction and satisfaction inherent in usability can neutralize adaptive preference.

P: Perhaps so. The close link between embodied interaction and subjective satisfaction in usability is a fair approach to neutralizing adaptive preference.

S: Part 11 also recommends applying multidimensional questionnaires for measuring subjective satisfaction.17 They make the user present opinions about learnability, clarity of terminology, and such. With these, subjective satisfaction could be considered to be equivalent to an assisted expert evaluation. Users take the role of experts, and satisfaction as a usability criterion becomes understood as perceived usability (Hertzum 2010) rather than hedonic satisfaction. Satisfaction becomes equivalent to users’ beliefs about the qualities of use.

P: Right. So, how shall we deal with satisfaction?

S: Maybe it doesn’t need to be mentioned. Maybe we could instead speak about “experienced worth” or “perceived worth.”

P: Or just “worth” as we discussed.

S: Maybe.

P: Do you think it would be too daring to wrap all this up …

S: … and propose a new formulation for usability?

P: Yes.

S: It definitely would be daring, but go ahead.

P: A capability-sensitive (Oosterlaken 2013) phrasing of usability would go something like this: the extent to which a product can be applied by the widest range of users to achieve their goals with appropriateness and sufficiency and their relationship to the worth of inputs, with or without satisfaction in the users’ context of use.

S: Hmm … Maybe we could speak about “life projects” instead of “context of use.” But as a rough version yours isn’t too bad.

P: Thanks. But I want to refine it. Do you have other suggestions?

S: I think the formulation is perhaps too long. Why don’t you remove the reference to the relationships of the indicators? I’d also leave satisfaction out. Saying satisfaction may or may not be included doesn’t add anything. Mentioning worth should be enough.

P: So it would be something like this: the extent to which a product can be applied by the widest range of users for appropriate, sufficient, and worthwhile achievements in their lives.

Applicability is the extent to which a product can be applied by the widest range of users for appropriate, sufficient, and worthwhile achievements in their lives.

S: That’s better. It’s good.

P: Would usability be usability anymore if we require these changes?

S: Accessibility and beneficiary-neutrality are already included in the ISO standard, and underlining their importance doesn’t conflict with the ideas and expressions of the standard in any important respects. Tolerance for emergence and conviction-critical use, however, would result in greater changes to the nature of the concept. Both are basically consequences of adjusting just one of the underlying assumptions of usability. That deals with dignity. Usability is not based on an idea that use would be an essential element of human dignity. If this requirement is added, the evaluation of use should include an ethical dimension and our suggestions become more necessary.

P: But as we noticed, usability gave us a good stepping stone.

S: It did.

P: So we could call what we have dignity-sensitive usability. Or perhaps we could call it capability-sensitive usability, because we’ve used the capability approach as our scaffolding.

S: We could consider another name too. We need a framework that’s capable of linking evaluation of particular interactions to more generic principles of a good life and good design, and usability without adjustments isn’t enough for that purpose. So maybe it would make sense to distance the framework from usability by using a different name.

P: Applicability?

S: That connotes taking initiative in defining how the design is used in addition to merely interacting with it. I don’t think I’m very clever in these language games, but “applicability” has the kind of meaning I like.

P: Shall we stick with that for now?

S: Let it be “applicability.” That doesn’t refer to ethics directly, but it does refer to personally relevant achievement. The lack of that was a problem we identified with usability.

P: I’m happy with the choice.

S: Good.

P: I think it’s almost time to present my one-liner to conclude the discussion, but before that I still have a question.

S: Yes?

P: Do you think the users’ roles we identified last time are still a good fit with applicability?

S: We’ve been painting a picture of a user who is more active than the fellows we discussed last time. You might be right. The previous roles don’t cover the new standpoint.

P: That of an applier. Do you think that would be an apt name?

S: Sure.

P: Fine. I think appliers’ interests are quite different from those of the others, in that they don’t want interactions that are optimized for particular tasks. They want to participate and define the purposes of design. That’s why any measurement of optimized use is in a way misleading. It’s a standpoint that makes one excited about opportunities to improve things. Perfection of design doesn’t give appliers opportunities to act, but a promise of something new does. Perhaps they don’t exactly want design to be bad, as that might be a hopeless starting point for fruitful appropriation, but they probably want design to be unfinished. An unfinished design doesn’t motivate them to use it, but to change it or perhaps change the scenarios of use. They probably don’t get excited about plentiful or few results or huge or limited consumption of resources within a given scenario of use. They would look for an ambivalence in design that leaves them the freedom to adjust and look for the opportunities to use it. If we want to be provocative, we could say that an applier wouldn’t like to be satisfied, because that wouldn’t stimulate her to act.

S: An interesting elaboration.

P: Thanks.

S: We might have here a standpoint from which the lack of results and excessive consumption of resources look attractive.

P: Yes.

S: But we need to be careful with this now. What the applier likes is not the lack of results and excess of resources, but a personally relevant opportunity for application and adoption. Maybe we could say that the indicators of quality of use, in their present form, mean little to her. She’s similar to the devotee. Neither of them care about usability or user experience, but for different reasons. For a devotee, getting something done is so meaningful that the quality of use doesn’t matter. For an applier, the actual use will be something different to the present use anyway, so why bother.

P: Do you think an applier is like an end-user innovator (von Hippel 2005)?

S: I wouldn’t require an applier to innovate with the design. It’s enough that she’s active in considering alterative ways to understand and appreciate the products. Perhaps she’s an end-user innovator of meanings.18

P: That’s a nice conclusion.

1Morten Hertzum (2010) has interpreted usability as an inclusive concept that covers widely different research interests and design practices. It includes universal usability, which aims at accessible solutions for everybody; situational usability, which refers to the quality-in-use of a system in a specified situation; perceived usability, which deals with subjective evaluation of a system; hedonic usability, which focuses on joy and pleasure rather than accomplishment-related criteria; organizational usability, which deals with people collaborating in organizational settings; and cultural usability, which addresses cultural differences between users.

2Oosterlaken (2013) speaks about “capability-sensitive design.”

3See, for instance, Sen (1985, 1993, 2000, 2010a), Nussbaum (2000, 2011), Alkire (2005), Robeyns (2005, 2006), and Gasper (2007) for generic discussion on the capability approach; Oosterlaken (2009, 2013) for the application of the capability approach to design ethics; and Pogge (2003), Jaggard (2006), and Reader (2006) for critical stands.

4The utilitarian approach.

5Rawls’ approach to distributional justice.

6Andy Dong (2008; Dong et al,. 2013), Ilse Oosterlaken (2009, 2013), and Murphy and Gardoni (2010) have linked the capability approach to participatory design, product service system design, risk management, and design for all.

7These include financial resources, economics, political practices and institutions, freedom of thought, political participation, social or cultural practices, social structures, social institutions, public goods, social norms, traditions, and habits (Robeyns 2005).

8Peter Corning (2012: 107) says that more than 90 percent of consumers’ income is spent on satisfying the basic needs of subsistence he has listed.

9Robeyns (2006: 371) says that by “having a common theoretical framework that allows for a range of applications … the capability approach opens up a truly interdisciplinary space in the study of well-being, inequality, justice and public policies.” Des Gasper (2007: 336) seconds this opinion by saying that “underdefinition allows everyone to perceive space for themselves in a project. It gives, fittingly, a lot of freedom for people of varied backgrounds to grow out from a small kernel in diverse ways, according to their interests and skills.”

10Searches with “usability” and “capability” as the terms return several hits, but in those capability refers to the organizational capability to develop usable products and does not deal with the capability approach and justice of design (Jokela 2004, Jokela et al. 2006).

11This is the ISO 9126 (1991) definition of usability.

12This is the ISO 9241-210 (2010) definition of user experience.

13See, for instance, Bevan, Kirakowsky, and Maissel (1991), Bevan (1992), and Corbett, Macleod, and Kelly (1993) for early discussions on the definition of usability.

14Martha Nussbaum’s (2011: 84–5) terms for the different capabilities are basic, internal, and combined capabilities. Basic capabilities are ones that a child inherits and naturally learns by being part of a community. Internal capabilities refer to the matured capabilities that the individual has developed with the support of her environment. Combined capabilities are internal capabilities exercised with external provisioning. Des Gasper (2007) speaks about potential that a person is born with, skills that one can acquire, and outcomes that appear with the use of external means.

15When the capability approach is seen as normative.

16Amartya Sen (1993) emphasizes, referring to Adam Smith (1776/2004), that appearing in public without shame is fundamental for an individual to lead a worthwhile life with dignity, and that avoiding shame requires the individual to wear appropriate apparel.

17For instance, SUMI (Kirakowski and Corbett 1993) measures usability along subjectively reported efficiency, affect, helpfulness, control, and learnability, and QUIS (Chin, Diehl, and Norman 1988) along scales titled screen, terminology and system information, learning, and system capabilities.

18She might be combining Eric von Hippel’s (2005) and Roberto Verganti’s (2009) ideas, sharing something also with Lévi-Strauss’s (1966) idea of bricoleur, creating new meanings by collecting and assembling things and ideas.